In my time spent exploring alternate-history fiction , I’ve come to the (no doubt entirely unoriginal) conclusion that there are two different types of publications in the genre; two broad “spheres” that nestle comfortably at either end of the genre and only occasionally overlap.

The first can perhaps be best described as “traditional” fiction, i.e. those novels and anthologies that are focused on plot and atmosphere and character development — whether they be an alternate-history crime thriller (In the Case Where Your Saviors Hide), legal thriller (Defying Conventions), naval-focused military history anthology (Those in Peril) or even espionage and politics (the classic Agent Lavender).

The second sphere consists of what its authors, editors and often readers seem to prefer labelling as “counterfactual” titles, far more formal and rigid essay-style counterfactual publications that focus exclusively on cause-and-effect explorations of a change or changes in a historical scenario. Almost inevitably these are military history-focused, with titles either following the what-if format or “X Victorious”, where X can stand for, variously, the Third Reich, Dixie, the Rising Sun and other nations or entities in history.

Both spheres have their pros and cons, and until very recently I had limited myself to reviewing titles in the traditional fiction sphere, as there were so many that I had discovered while wading my way through Kindle listings and social media posts. However, in my teenage years I had been an avid reader of counterfactual military history collections, and I still have a certain fondness for them. So when I discovered that Greenhill Books and Frontline books — the main publishers of many counterfactual collections — had significantly reduced the prices of many of their titles in ebook format, it seemed like the ideal time to dive back into that sphere.

If there was one common element that united all of the titles I purchased, apart from their publishers, then it was author and editor Peter G. Tsouras. Tsouras is one of the most prolific writers in the counterfactual history sphere, not only editing (and often contributing to) anthologies focused on specific scenarios, but also acting as sole author of a number of counterfactual history novels.

I have to admit my reading preferences owe a great deal to Tsouras, because the first alternate-history book I ever read was his seminal Disaster at D-Day, given to me by my grandfather from his own collection; it was an older copy, the cover far less restrained than later editions, with its blood-red background and bright yellow text that seized the attention of the eyes, flanked by the US, British and Nazi flags. Barely ten years old, and raised on a potent diet of my grandfather’s wartime memories, history books, the speeches of Winston Churchill and the Daily Mail, reading Disaster at D-Day was like reading some blasphemous text that went against all I held to be sacred and true. Omaha Beach was stained red with blood as Rommel’s Panzers advanced to the beaches, and British forces fought a valiant holding action before joining their American comrades in death or imprisonment. Between Disaster at D-Day and The Guns of the South from Harry Turtledove, my reading path would never be the same again.

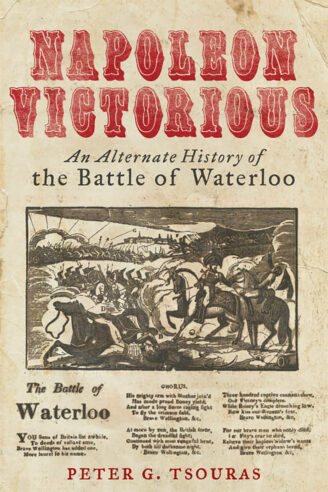

It seemed fitting, therefore, that I would return to the works of Tsouras, and one work in particular that was on sale caught my eye: his latest novel, the provocatively-titled Napoleon Victorious, that posited a world where Napoleon I overcame Blucher and the duke of Wellington in 1815. That delicious feeling of hallowed tenets being subverted welled up in me again — Waterloo had formed part of my childhood reading as much as D-Day, the Battle of Britain and El Alamein in the pantheon of British military victories — and I decided to read and review it first.

That decision was aided by the superb cover art, which has the look of an early-eighteenth-century newssheet, complete with faded background, period-appropriate font and text placement, and a black-and-white inked depiction of the alternate Battle of Waterloo. It’s a fantastically immersive piece of cover art, one that I’d love to have as a high-quality print, and it’s a shame I can’t see in the book who to credit for it. Combined with the ridiculously low price, it’s sure to attract readers.

Interestingly, Tsouras’ approach to Napoleon Victorious appears to be an attempt to bridge both spheres in the genre. The core of the book is set in the style of an academic essay or history book; a series of chapters that explore the alternate 1815 campaign in chronological order, complete with footnotes. But Tsouras injects a great deal of atmosphere and characterization into the book than might be expected from a title that, from outward appearances, is set firmly in the counterfactual history sphere.

It opens with a short prologue giving the point of view of Napoleon’s young son as he attends his father’s funeral in a France united from Napoleon I’s victories in 1815 and afterward. This well-written section not only helps to draw the reader into the world Tsouras is depicting, but also dispels the idea that this will be a dry textbook-style history. Then cleverly, in the very next chapter, Tsouras provides an incisive introductory essay that lays out his interest in Napoleon, his love of alternate history and finally a succinct summation of the decisions that led to Napoleon losing in 1815 in our reality — the exact sort of chapter that would be found in a solely counterfactual history title in the genre.

Then we go into the alternate history itself, though to his eternal credit Tsouras spends a good number of chapters laying out the (entirely historical) background for the campaign, beginning with Napoleon’s return from exile and the corruption and decadence of the Bourbon monarchy that drove so many soldiers and citizens into his waiting arms. The changes made by Tsouras to the time period are subtle at first, but soon start to gather pace, resulting in a different opening to the Waterloo campaign and then much more radical changes as the narrative progresses. While I’m not hugely familiar with the intricacies of the period, and the campaign itself, none of the changes introduced by Tsouras seemed unrealistic or unfeasible to this layman.

Tsouras keeps the narrative flowing well, making easy work of what could have been a dry and confusing series of battle descriptions, especially when considering that it rapidly devolves into counterfactual history. He achieves this by focusing on personalities, and especially the complex and ever-shifting relationships between Napoleon and his marshals and the marshals themselves. It makes fascinating reading, more so because all of the relationships, friendships, grudges and out-right hatreds have developed prior to the Waterloo campaign and are therefore entirely historical. Tsouras obviously put in a lot of research and successfully gets across the complex web of paranoia, loyalty, faith, threats and outright bribery that meshes together Napoleon and his senior staff.

There’s a great use of resources, and Tsouras’ research is second to none as evidenced by his detailed footnotes and even the fictional sources he cites towards the end of the book, as he alters the historical narrative (helpfully denoted by an asterisk in the endnotes) sound fascinating. I often felt regret that I would never be able to read them. The only real issue I had with Napoleon Victorious was one that I’ve never come across before — essentially, the author does his job too well. It was never entirely clear, as the narrative progressed, when exactly things began to change and became ahistorical, propelling Napoleon toward victory rather than defeat. The use of fictional citations helped somewhat, but the majority of those are to be found in the chapters dealing with the actual fighting; I still have no real concept of what change (or more likely changes) Tsouras made to the timeline. Everything is so well-written, and the narrative flows so smoothly, that it was only about two-thirds of the way through Napoleon Victorious that I realized I had no idea how we had got from factual to counterfactual.

As such, this title might best either be for someone unfamiliar with Waterloo or incredibly familiar with it. For someone in between, like me, it doesn’t have enough of an explanation of the points of divergence that Tsouras uses. Thus at times it can even come across as perhaps too biased, too perfect for Napoleon, with success or good fortune rarely, if ever, in the Allied side.

However, as I said, this is a rather unique issue that I’ve never come across before, and in the hands of the right type of reader it may not be a criticism at all. Regardless of that, Napoleon Victorious is a fantastic read, never dry or boring, driven by Tsouras’ detailed knowledge of the Waterloo campaign and the personalities on all sides of the conflict. I read it in a couple of days — a personal record for a book in the counterfactual sphere of the genre, and can heartily recommend it. Napoleon Victorious attempts, even unknowingly, to straddle both spheres of the alternate-history genre, and is remarkably successful in doing so.

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.

1 Comment

Add YoursI would love to see something similarly done from a Soviet-captured Von Braun who smoothed things over between Korolev and Glushko…the latter two becoming friends. Glushko always struck me as a tragic figure—-the Salieri of the Chief Designers.