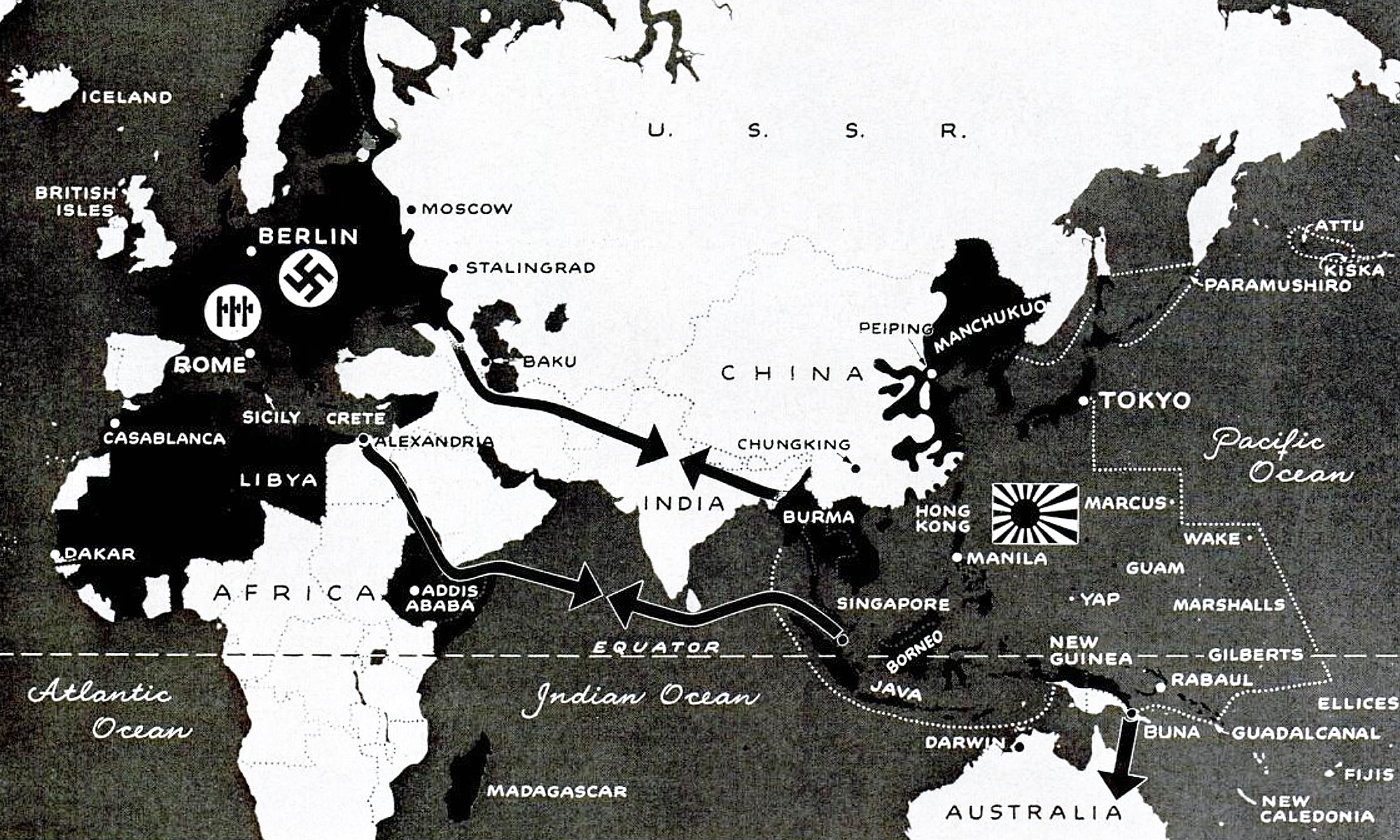

1942 was a bleak year for the free world. Adolf Hitler ruled an empire stretching from Dakar in West Africa to Spitsbergen (now Svalbard) in the north to the Caucasus in the east.

On the other side of Eurasia, his ally Japan controlled Manchuria, coastal China and all of Southeast Asia as far west as Burma.

The fear was that Germany would invade the Middle East and link up with Japan in India. Britain, cut off from its empire in Asia, could then be forced to sue for peace. The Soviet Union would be boxed in.

The weak link in the Axis was Italy. British and Commonwealth forces had ended Italian rule in Ethiopia in 1941. With American help, they were able to drive the Germans and Italians out of North Africa the following year. The next step was an Allied invasion of Europe from the south.

War on three fronts

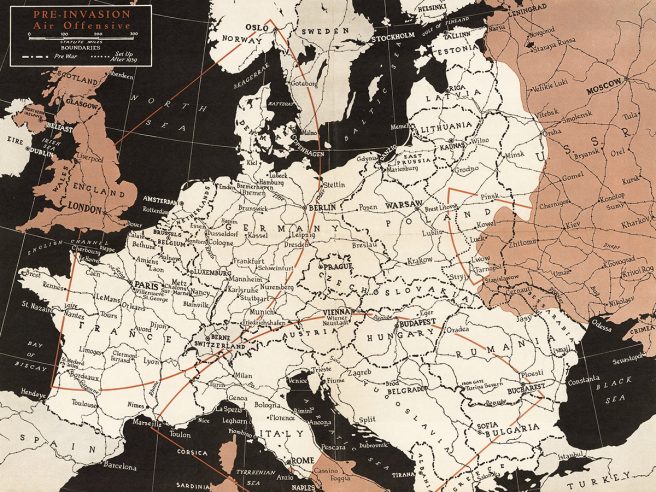

By 1943, the expectation was that the Allies would attack Europe from three directions.

Joseph Stalin’s Red Army had started pushing the Germans back in the east. The liberation of Sardinia would open up Italy and serve as a stepping stone to southern France. The Aegean Islands led to Salonika (now Thessaloniki) and the Balkans.

The big uncertainty was where the Allies would land in the west. Options included the beaches of France, the Low Countries and a direct assault on the north German coast, which could be combined with the liberation of Denmark and Norway.

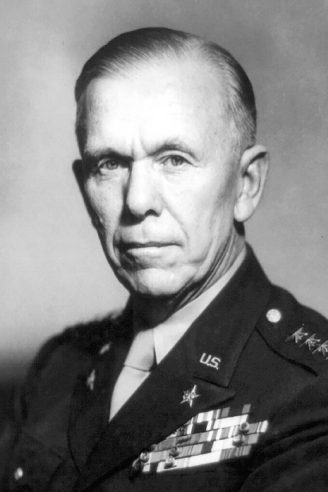

Dwight Eisenhower, who had successfully managed Allied operations in North Africa, was named Supreme Allied Commander in Europe by President Franklin Roosevelt in December 1943, passing over Army chief George Marshall, who, as US army chief of staff, nevertheless played a key role in designing the Allied victory in Europe (and later, as defense secretary, its postwar reconstruction).

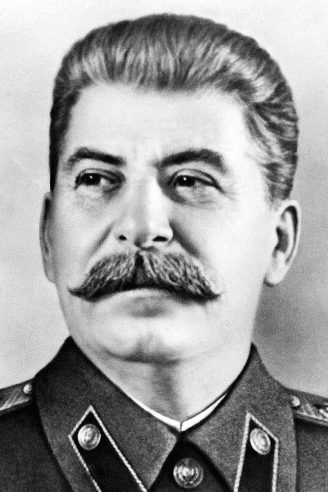

In the East, Soviet supremo Joseph Stalin was more involved in planning military operations than Western leaders, despite his poor record in the period leading up to and during the German invasion. Georgy Zhukov, who had stopped the Germans at Stalingrad, became the principal Russian commander.

War in the air

Hitler responded to the fall of French West Africa by occupying collaborationist southern France, which was governed by World War I hero Marshal Philippe Pétain from Vichy. The Vichy army did not resist, but Admiral François Darlan scuttled the French fleet in Toulouse to prevent it falling into Nazi hands.

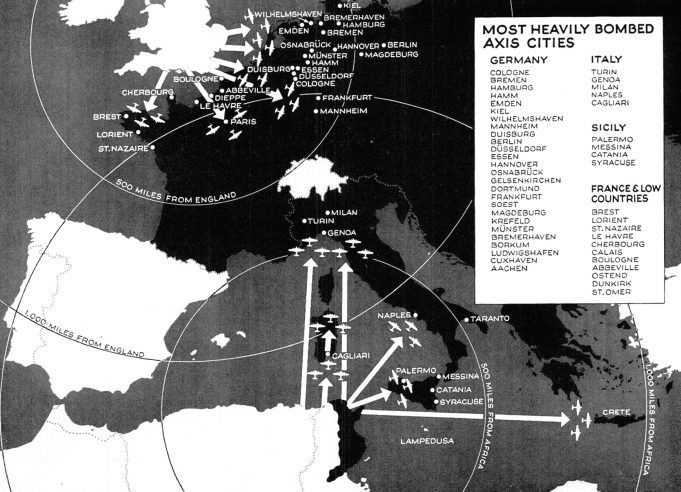

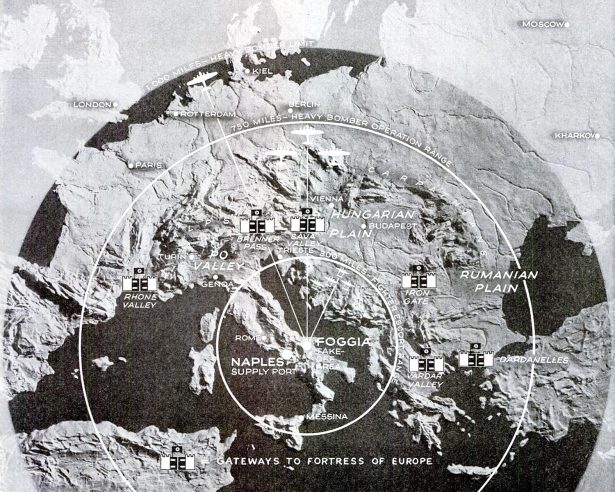

Victory in Tunisia put Italy within reach of Allied bombers. In order to weaken the Axis war industry, the Western Allies launched the Combined Bomber Offensive in June 1943. Its priorities — especially for the Americans — were to destroy the German oil and weapons industries, but demoralizing the Axis population through deliberate bombing of civilian areas was a secondary objective — especially for the British. Even though the Nazis’ similar attempt to break the will of the English population with the Blitz two years earlier had famously failed.

Some 37,000 civilians were killed in the firebombing of Hamburg alone. The city was a military target for its petroleum storage sites and shipyards, but indiscriminate bombing also wiped out residential areas. Cities in the industrial Ruhr area suffered the same treatment.

In Italy, the “industrial triangle” of Genoa, Milan and Turin was bombed. The wider streets of Italian cities and minimal use of wood made them less vulnerable to firebombing.

Germans stopped at Kursk

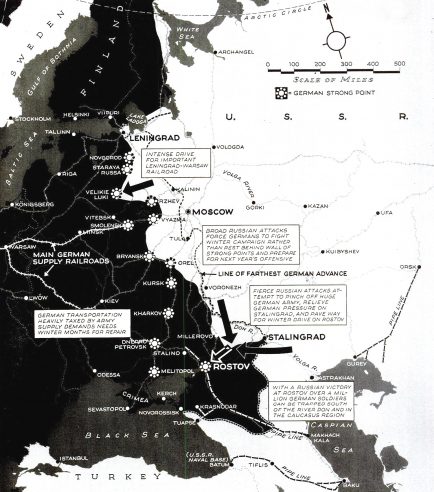

Meanwhile the Russians had pushed the Germans back on three fronts: north of Rzhev, between Leningrad and Moscow; in the bend of the Don; and south of Stalingrad. The latter two movements met up at Rostov, trapping 250,000 troops of General Friedrich Paulus’ German 6th Army and parts of General Hoth’s 4th Panzer Army behind enemy lines.

Hitler attempted one last Blitzkrieg in the East. He reinstated Heinz Guderian, who had successfully commanded the armored offensive through the Ardennes during the Battle of France but failed to capture Moscow two years later, to lead an attempt to recapture the territory that had been lost. His two-pronged Panzer offensive ran almost immediately into a Soviet counteroffensive, Operation Kutuzov, named after the Russian general credited with saving Russia from Napoleon in 1812. Nearly 300 German and some 600 Soviet tanks met near Prokhorovka, where they fought probably the largest tank battle in history (usually named after the nearby city of Kursk).

Although the outcome was not the Soviet triumph propaganda would later make it out to be — the Russians lost five times more men and tanks than the Germans — the Panzers were stopped and Hitler, alarmed by the simultaneous Allied invasion of Sicily, canceled the operation; a first. The Kursk offensive would be Germany’s last on the Eastern Front.

Invasion of Sicily

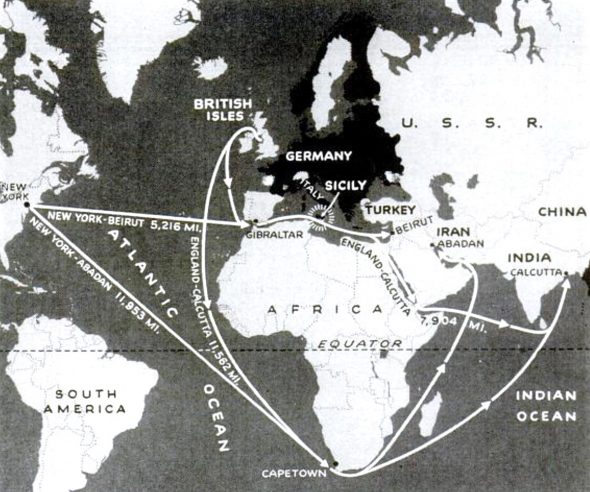

After the liberation of North Africa, the Western Allies debated where to strike next. The British argued for an invasion of Sardinia or Sicily in order to knock Italy out of the war and perhaps lure neutral Turkey into the Allied camp. The Americans were persuaded by the effect the removal of Axis air and naval forces from the islands would have on shipping routes. Safe passage through the Suez Canal took 3,500 miles off the journey from Britain to Calcutta. Access to the ports of Beirut in Lebanon and Abadan in Iran cut the distance from the United States to Russia in half. This had the same effect on Allied war strategy as the addition of several million tons of new shipping.

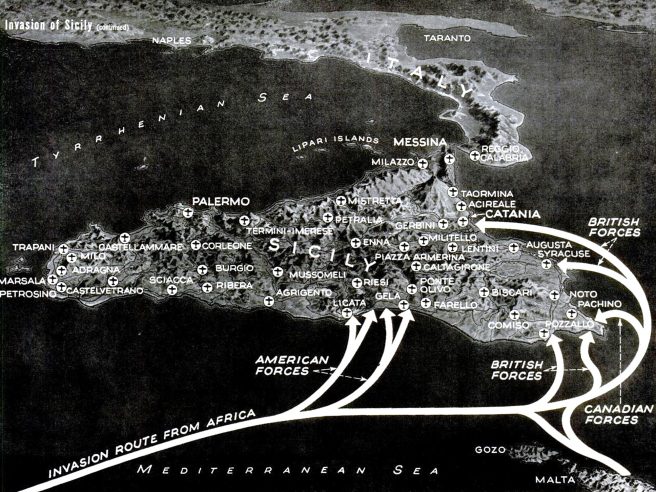

As soon as Sicily was selected, the English mounted a deception operation named Mincemeat to convince the Germans the real target was Greece. A corpse disguised as a British officer was washed ashore in fascist Spain carrying documents purporting to reveal the Allied invasion plans. It worked: the Spaniards passed the documents onto the Germans, who moved three Panzer divisions, commanded by Erwin Rommel, to Greece. The operation was the inspiration for a 2021 motion picture starring Colin Firth (our review here).

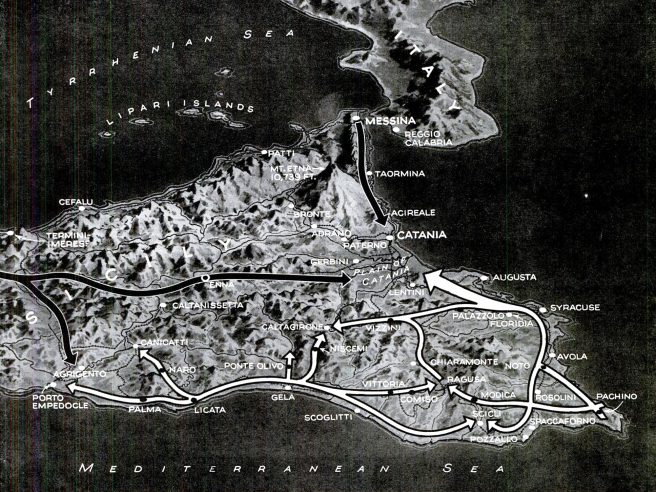

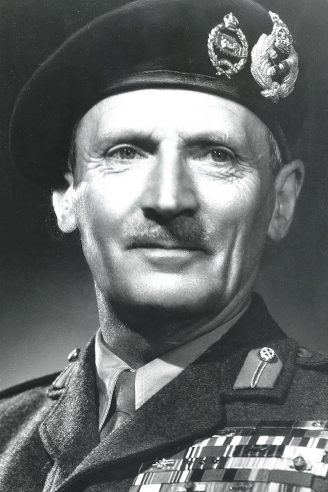

Landings were made at seven main points on July 10 after four weeks of aerial bombardment of railways, roads, airfields and communication centers. Fighter planes protected the landing of some 2,000 ships. The Americans, commanded by George Patton, met the strongest resistance at Gela. In the east, British and Canadian troops commanded by Bernard Montgomery ran into comparatively little opposition until they were farther inland.

The first week of the battle brought the Allies near Agrigento and to Canicatti on the west, to Niscemi, Vizzini and Palazzollo in the center, to the edge of the Catania plain on the east. Most Axis forces had been stationed in the west of the island and were forced to move inland to fight the Allies.

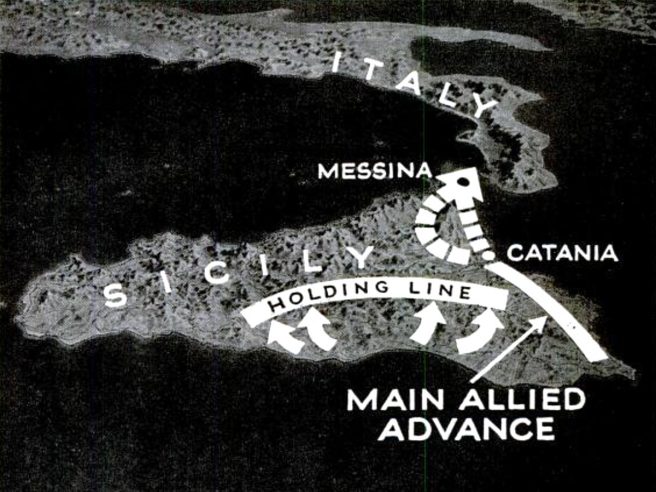

The expectation was that they would try to pin the Allies down, but instead the Axis gave up after one week of futile defense. It took another week to withdraw some 50,000 German and 60,000 Italian men across the Strait of Messina. The Allies could do little to interfere with the retreat, since the narrow straits were protected by heavy guns on both ends.

Fall of the Ostwall

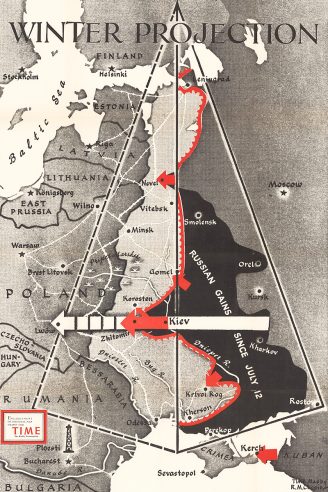

After their victory at Kursk, the Soviets took the initiative on the Eastern Front. The Germans attempted a defense at so-called Panther-Wotan Line, running from the Gulf of Finland in the north to Crimea in the south.

Despite its German name, Ostwall, this was nothing like the Atlantikwall or the French Maginot Line, but rather a hastily constructed perimeter of defenses, many on the right (west) bank of the Dnieper. The head of Army Group North, Field Marshal Georg von Küchler, refused to even refer to a “Panther Line” in his section, worried that it might instill overconfidence in his troops.

Zhukov rushed 2.6 million Soviet soldiers to the Dnieper to stop the Germans digging in along the 300-kilometer front. The line was weakest at its southern end, where it departed west from the river to prevent the Crimea from being cut off. That is exactly what Zhukov did, trapping the entire German 17th Army on the Black Sea peninsula. The Soviets then established bridgeheads across the Dnieper, which the Germans were unable to dislodge. Kiev was taken by December. One SS division held out in Narva, Estonia for six more months.

Invasion of Italy

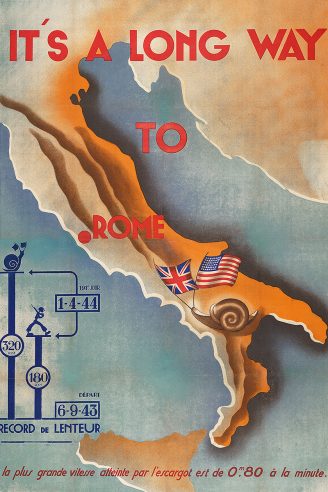

The success of the Sicily Campaign convinced the Americans an invasion of mainland Italy was preferable to one of France, which the British thought premature. Especially after Mussolini was ousted by his own cabinet in July. The hope was that a quick invasion might hasten Italy’s surrender and trap the remaining German forces in the country.

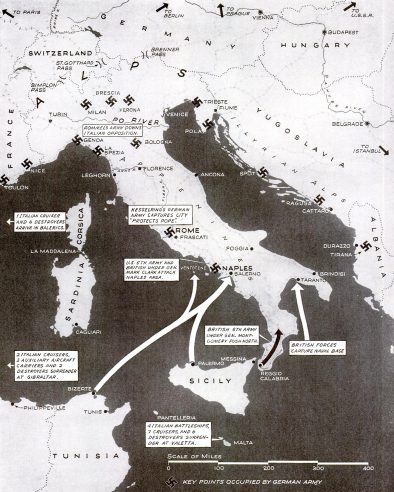

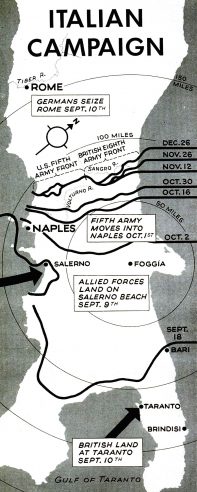

Eisenhower planned a two-pronged attack. Montgomery’s Eighth Army would cross the Strait of Messina from Sicily and link up with an amphibious assault on Taranto in the south. The American Fifth Army, under Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, and supported by the British X Corps, would land south of Naples, at Salerno.

Montgomery’s attack went as planned, and met little resistance. The German commander in Italy, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, rightly calculated that the main thrust of the Allied invasion would come elsewhere.

The attack on Naples was preceded by an unexpected armistice with Mussolini’s successor government, signed in Cassibile by Eisenhower’s chief of staff, Major General Walter Bedell Smith, for the Allies and Brigade General Giuseppe Castellano for the Italians.

Kesselring heard the news and immediately implemented a plan to disarm his former allies. German troops simultaneously attacked Italian positions in the Balkans and southern France. The Italian Royal Family fled Rome. Mussolini was freed by German paratroopers from his prison in the Apennine Mountains. Clark’s invasion force of 170,000 now faced an all-German defense of 35,000 men at Salerno, commanded by Heinrich von Vietinghoff.

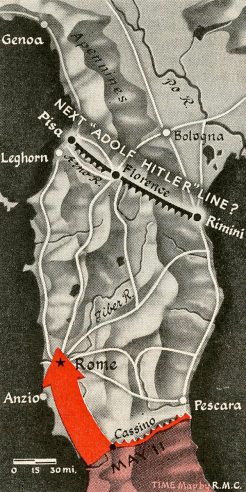

They stubbornly resisted for eight days, giving the rest of the German army time to retreat behind a network of defensive lines south of Rome. In October — Montgomery was pushing the Eighth Army up north from Taranto — the Allies reached the Volturno Line, stretching from the Volturno River in the west to the Biferno River in the east. The Germans gave ground slowly, buying themselves time to complete the Barbara Line.

This process repeated itself various times that winter, with the weather and terrain benefiting the defending Germans. It took the Allies until 1944 to reach the main Gustav Line, centered on the town of Monte Cassino through which ran the highway to Rome.

The capture of the Foggia Airfield Complex made it possibly for the Allies to daily bomb German industries in Bavaria and Bohemia. The expectation of some observers was that the Allies would push north and invade Germany through the Alps. In fact, fighting continued in northern Italy against Mussolini’s puppet Italian Social Republic until the end of the Second World War in Europe.

Eastern Front

While the Western Allies hashed it out with the Germans in the mud and the cold of the Apennine Mountains, the Red Army was taking back the lands Germany had seized in Operation Barbarossa. The siege of Leningrad was lifted after 900 days. The Soviet offensive in the Baltics was slowed when Estonians joined the Axis in hopes of regaining their independence.

The Soviets made headway everywhere else. The capture of Bryansk and then Smolensk forced the Germans to retreat on the central front. In the south, Army General Rodion Malinovsky took his home town of Odessa, breaking its railway connection to Berlin. Crimea was liberated the following month. Hitler sacked Erich von Manstein as head of Army Group South and replaced him with Johannes Frießner.

The Germans expected Malinovsky would continue his Ukrainian offensive in the summer, since that appeared to offer the shortest route to Berlin. Instead, Zhukov threw 2.3 million men against a mere 800,000 German defenders in Belarus. Minsk was quickly taken and some 100,000 German soldiers were captured. By August, Army Group Center had lost half its strength and the Soviets had reached the prewar border of Poland.

D-Day

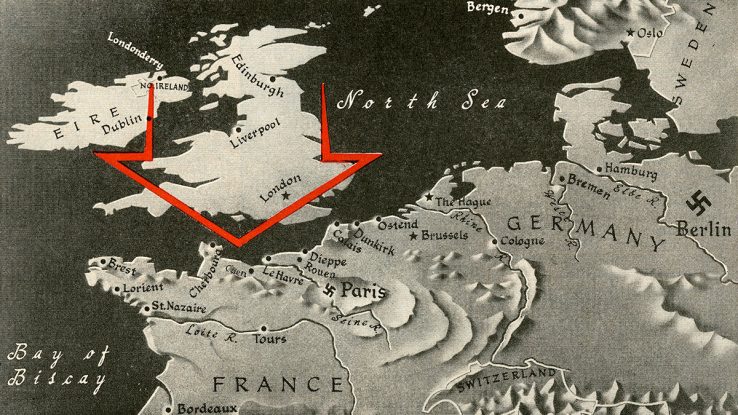

The Allies had been planning the invasion of France since 1943. They considered four landing sites: Brittany, Cherbourg, Normandy and Pas-de-Calais. The first two were quickly rejected. The Germans could have trapped the invading forces on either peninsula. Pas-de-Calais is closest to Britain, but the Germans considered it the most likely landing zone for that reason and had heavily fortified it. Arguing against Normandy was its absence of ports, but it commanded good routes to Cherbourg and Paris. The English developed artificial “Mulberry harbors” to make an invasion of Normandy feasible.

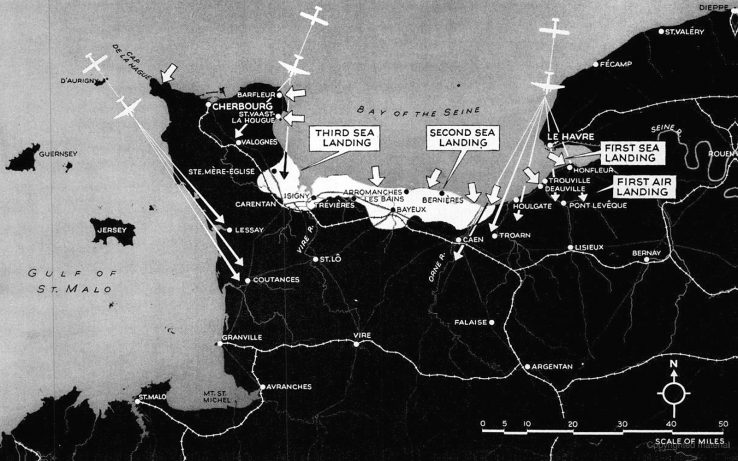

At the insistence of Generals Eisenhower, who commanded the overall invasion, and Montgomery, who commanded its land forces, three planned amphibious landings were expanded to five to allow a wider front and hasten the capture of the Cotentin Peninsula.

An elaborate deception was undertaken to convince the Germans the invasion would come at Calais, including the creation of a fictitious First United States Army Group under the command of the illustrious General Patton. The deception was so convincing that it took Hitler seven weeks after the invasion to order to redeployment of forces from Calais. General Omar Bradley, Eisenhower’s righthand man, called it the “single biggest hoax of the war.”

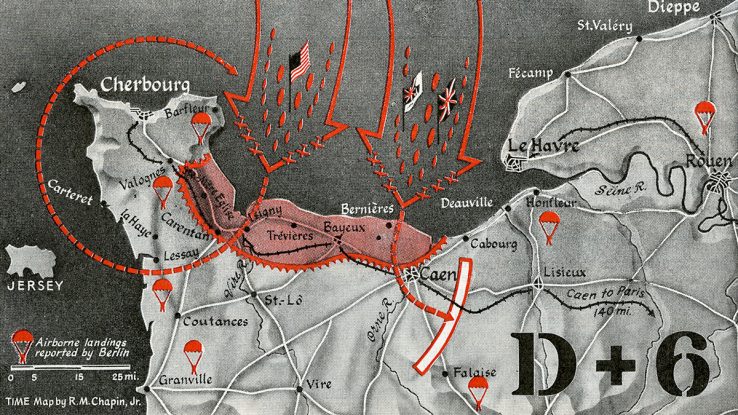

In the early hours of June 6, over 2,200 American, British and Canadian bombers attacked the beaches and bunkers of Normandy. Minesweepers began clearing the English Channel before dawn. A fleet of 1,213 warships, 4,126 landing craft, 736 ancillary craft and 864 merchant vessels — the largest ever assembled — commanded by Admiral Bertram Ramsay dislodged some 160,000 men in one day, of whom around 10,000 were killed on the beaches.

German defenses under Erwin Rommel were overwhelmed. The Atlantikwall, a series of fortifications stretching from the north of Denmark to the south of France, hadn’t been completed. Rommel’s men were thinly spread across the entire length of it and included many conscripts and volunteers from subjugated peoples of the Soviet Union, the so-called Ostlegionen, who weren’t the most motivated to fight for Nazi Germany.

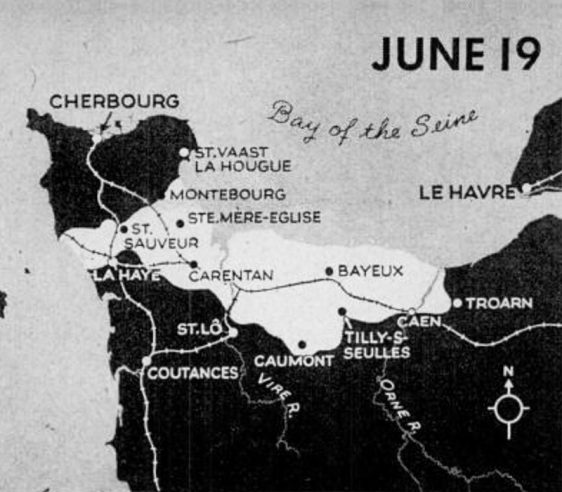

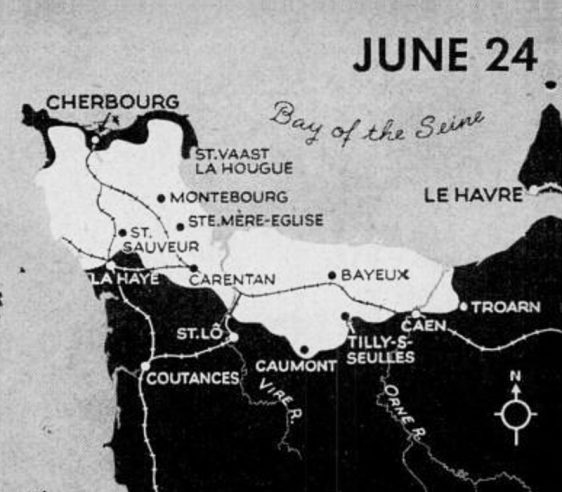

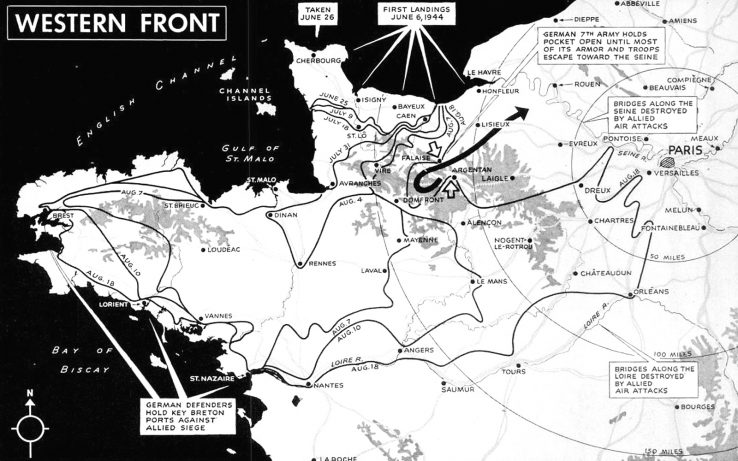

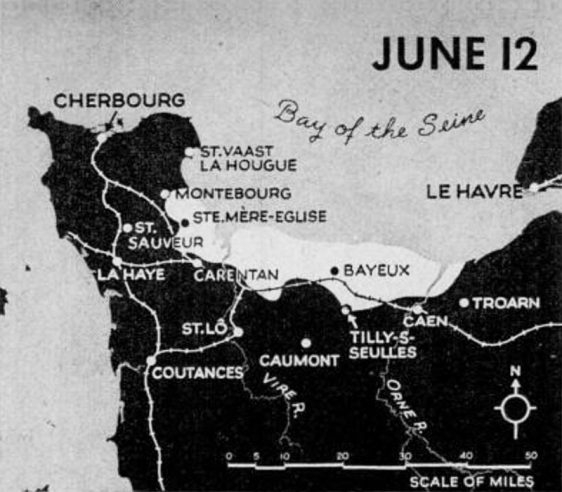

It took the Allies three weeks to reach Cherbourg and another three weeks to defeat the Germans at Caen. After an unsuccessful counterattack south of that city, which trapped some 50,000 German soldiers, the Americans, British and Canadians were able to make more headway.

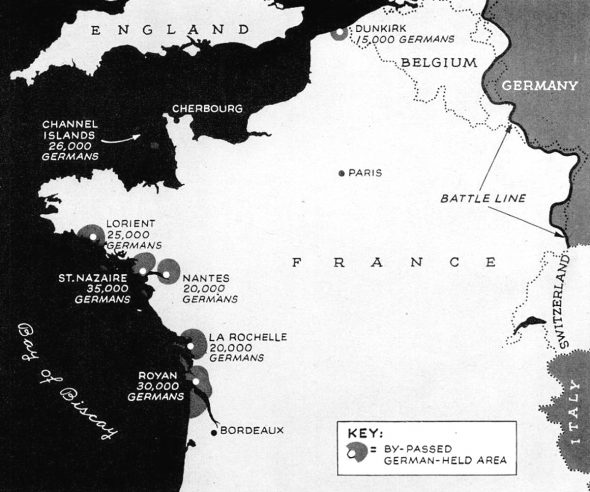

Advances during the summer put First and Third Army in position for the opening blow. Third Army, under Patton, was thrown through a hole west of Saint-Lô. Pushing past to Avranches, it burst into Brittany and there exploded in all directions. Patton roared south and west for the ports of Brest, Lorient, Saint-Nazaire and Nantes. His second great sweep broke through Laval and Le Mans in the direction of Paris. From Le Mans, one strong arm turned northward to encircle those German troops still holding the British and Canadians in Normandy.

By then, Rommel had been injured in a car accident and replaced by Günther von Kluge, who was himself replaced by Walter Model when the Allies landed in southern France on August 15. Rommel and Kluge committed suicide after Hitler became aware of their involvement in the July 20 plot against him.

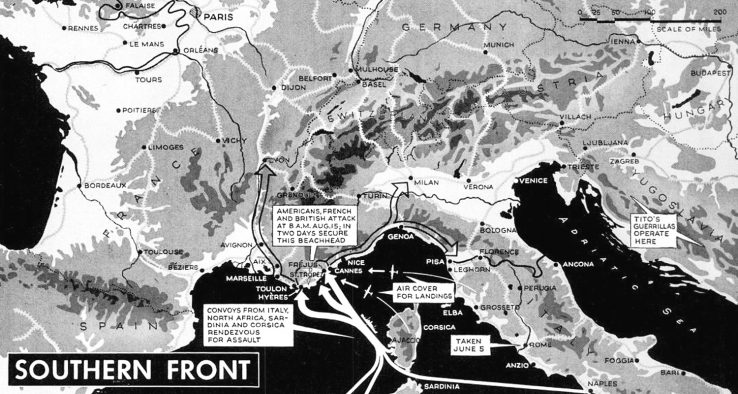

Dragoon and the Liberation of Paris

A fleet of 800 Allied ships put General Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army ashore in the area between Toulon and Cannes on August 15. The landing, Operation Dragoon, was preceded by three days of bombing and the greatest ship-to-shore barrage ever used in the Mediterranean theater. Airborne troops were first to attack, cutting roads behind the coast at night.

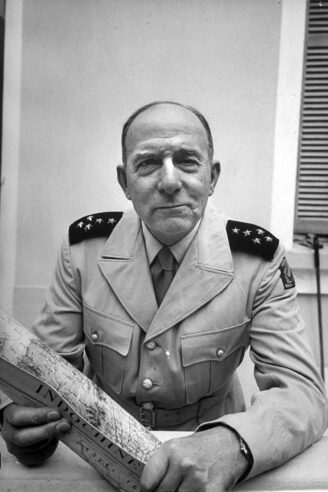

Charles de Gaulle has persistently lobbied for an invasion of southern France. Free French troops, commanded by Major General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, for the first time played a major role. Their numbers were swelled by French Resistance fighters.

The Resistance also rose up against the Germans in Paris. That gave Eisenhower a dilemma. He had wanted to bypass the city for fear of having to conquer it street by street Stalingrad-style. De Gaulle’s nightmare was another Warsaw: the Polish Resistance had taken up arms against the Germans, but the Red Army refused to come to their aid, resulting in a bloodbath.

De Gaulle prevailed, and Free French forces commanded by General Philippe Leclerc and operating American Sherman tanks entered the city on August 24. Paris was officially liberated the next day. The Germans retreated across the Seine on August 30.

Stalin watches Warsaw burn

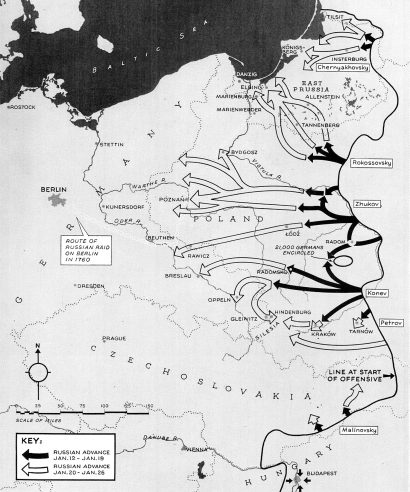

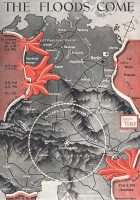

In the east, the Russians were close to East Prussia and started a more important drive aimed at Kraków and German Silesia.

But when they reached the Vistula River, Stalin ordered them to stop. The Soviet Union supported the communist Polish Committee of National Liberation over the far larger, but not pro-Russian, Home Army. The latter called the Warsaw Uprising, which Stalin needed to fail in order to pave the way for a communist takeover after the war. As many as 200,000 Poles were killed in the German repression, which lasted 63 days. Some 700,000 fled and more than half of Warsaw was leveled to the ground.

A national uprising in Slovakia was also put down by the Wehrmacht. The Red Army was more active farther east. It cut off and destroyed the remaining German presence in Romania, triggering a coup d’état by King Michael I against Hitler’s ally Ion Antonescu. In neighboring Bulgaria, communist partisans captured and killed Axis sympathizer Prince Kiril.

Alpenfestung

With Allied armies advancing from three directions, fears mounted that the Nazis might be preparing a last stand in the Alps. There were stories in late 1944 and early 1945 of massive troop concentrations in the area, underground factories and enough supplies to sustain an army for years.

The Alpenfestung turned out to be little more than German propaganda, but it was effective: in order to stave off a German fight to the death, Eisenhower pursued a broad-front strategy in the west rather than a direct assault on Berlin. That would give the Soviets time to reach the German capital first.

Click here to learn more about the German national redoubt that wasn’t.

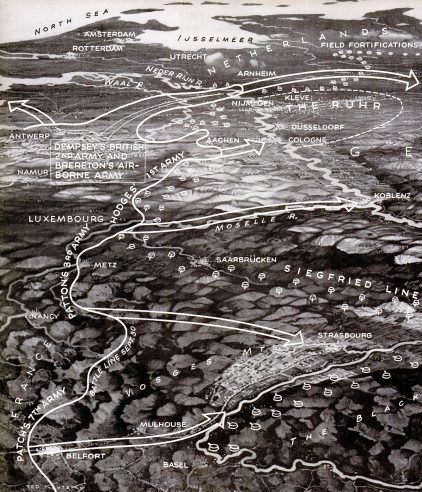

Approaches to Germany

Toward the end of 1944, between two and three million Allied troops were fighting the Germans across a 700-kilometer front stretching from the North Sea coast to the wooded Vosges. Fluid fighting in August coagulated into bitter battles before the ramparts of Aachen, Belfort, Metz and the interlocked defenses of the Siegfried Line.

To the south, Patch’s Seventh Army probed the ancient bloody ravines of the Belfort Gap. Catholics and Protestants fought there during the Thirty Years’ War. Napoleon defended it successfully for 113 days against the Austrians in 1913-14. The 103-day defense of Belfort against the Prussians in 1870-71 was a glorious episode in another humiliating French military history. In November, the German front snapped under Patch’s pressure, resulting in sudden Allied advances that liberated Mulhouse and Strasbourg, and placed American forces along the River Rhine.

Patton’s Third Army assaulted the formidable citadel of Metz with its seven forts. Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges’ First Army hammered at defenses stretching from Aachen to the Moselle. Farthest north, in the watery lowlands, the British Second Army and First Airborne Army raced to outflank the Siegfried Line and capture the precious ports of the Netherlands.

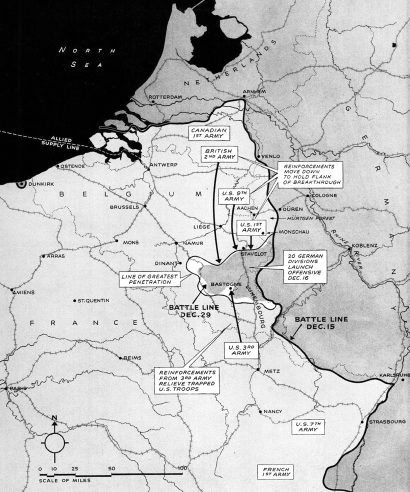

Ardennes Offensive

Hitler didn’t make his last stand in the Alps but in the Ardennes, the same forest on the border of Belgium and Luxembourg through which his armies had invaded France four-and-a-half years earlier.

The plan was to swing north to Antwerp and split the American and British armies, but the offensive only managed to make a bulge some 80 kilometers into Allied-held territory. Hence the American name “Battle of the Bulge”.

The Germans threw 400,000 men into the battle, their state-of-the-art Tiger II tank, jet-propelled planes and flying bombs. They took the defending US First Army by surprise. The Americans were eventually able to regroup on the Elsenborn Ridge to the north and around Bastogne in the south, buying time for reinforcements to arrive.

That, in the end, was the only strategic setback Hitler inflicted on the Allies: diverting four armies from their main drives toward the Ruhr and Saar. Far from forcing the Western Allies to sue for peace, as the Nazi dictator had hoped, it merely delayed their invasion of Germany by a few weeks.

For the Germans, the consequences were worse. They had wasted their last reserves in a hopeless offensive. Remaining forces throughout the West were hurried back to defend the Siegfried Line, the country’s last hope.

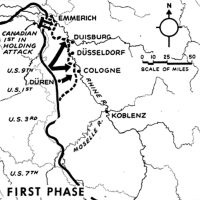

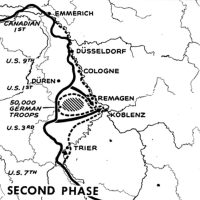

Across the Rhine

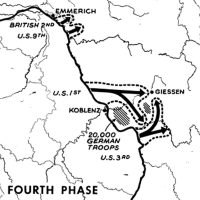

The Allied invasion of Germany was delayed by another two weeks when the Germans flooded the Rur Valley by destroying the gates of the Rur Dam. Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt asked Hitler’s permission to withdraw east behind the Rhine but was denied. By the time the water subsided, Von Rundstedt’s troops were sitting ducks. The Allies took 280,000 prisoner.

At Hitler’s insistence, the Germans fought hard to slow the Allied advance on the Rhine, probably costing them another 400,000 casualties. It only delayed the inevitable. By the end of March, the Allies had crossed the Rhine at four points.

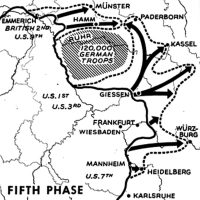

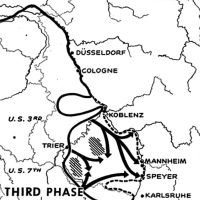

The British fanned out northeast toward Hamburg and Denmark. US Ninth Army became the northern pincer of the encirclement of the Ruhr industrial area, First Army the southern pincer. Patton’s Third Army dove south into Bavaria.

Last stretch to Berlin

Churchill and Patton urged Eisenhower to make a push for Berlin, but Bradley cautioned against it, calculating it might cost another 100,000 casualties while eastern Germany was destined to be occupied by the Soviets anyway. His caution prevailed: Eisenhower ordered his armies to halt when they reached the Elbe and Mulde Rivers.

The Soviets commenced their final push on April 15 with one of the largest artillery barrages in the history of the war, firing one million shells on the German positions west of the Oder. Zhukov sent wave after wave of Red Army soldiers across the river while the shelling continued, inadvertently killing some of his own men in the process. By the time they broke through, Berlin was a mere 90 kilometers away.

Hitler, still refusing to give up, ordered his generals to muster whatever forces they could for the defense of Berlin. On his birthday, April 20, Zhukov was close enough to start shelling Berlin’s city center, where Hitler was holed up in a bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery. Helmuth Weidling’s defending garrison consisted of depleted and disorganized Army and SS divisions, poorly trained Hitler Youth and Volkssturm recruits, many of them old men. They were no match for the Red Army. On May 2, the city’s defenders surrendered. Hitler had committed suicide two days earlier.

Remains of the Reich

By the time Hitler’s successor, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, surrendered on May 8, Nazi Germany still controlled a sliver of the North Sea coast, stretching from the Dutch port of Rotterdam in the west to the islands of Denmark in the east; almost the entirety of Norway; the Courland Pocket on the Baltic Sea; and most of what became Austria and the Czech Republic.

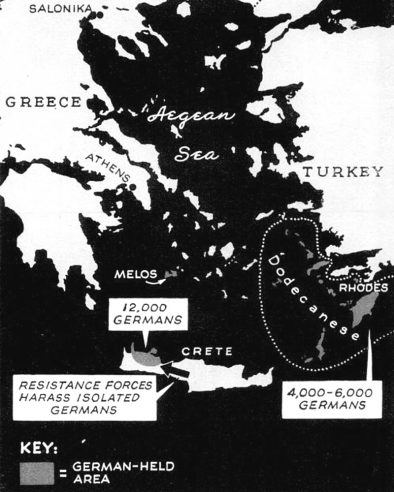

A few Axis troops had also held out in U-boat bases in western France, on the Channel Islands, Crete and the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea. German soldiers on Spitsbergen had lost radio contact with Europe and didn’t surrender until they were picked up by Norwegian seal hunters on September 4, two days after Japan’s surrender in the Pacific had ended World War II.