Titanic.

It’s a name that conjures up images. The grand ocean liner of the Edwardian era caught up in fate and circumstances on its maiden voyage. A ship full of the rich and famous, as well as those hoping for a new life. All of their lives intertwined when the vessel hits an iceberg in the mid-Atlantic. And without enough lifeboats to save them all from the freezing water around them. It’s a tragedy that has played out in every form of mass media since that April night in 1912, from books and songs to computer games and movies.

But did it have to be so?

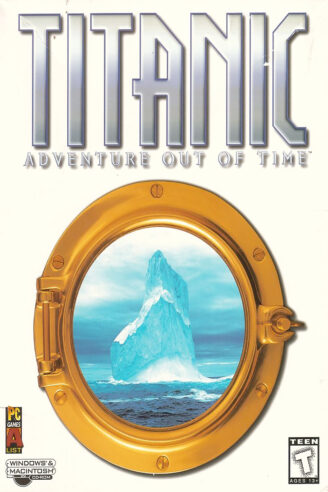

Of course, the Titanic has played a role in the alternate-history genre all its own. The 1996 computer game Titanic: Adventure Out of Time — whose CG representations of the liner became a mainstay of late-90s documentaries about the Titanic — put players in the place of a British secret agent given the opportunity to return to a failed mission, with the hours leading up to the disaster affording a chance to avoid both world wars and the Russian Revolution.

Jack Finney’s novel From Time to Time (1995) saw a time traveler attempting to prevent the First World War by ensuring the survival of Major Archibald Butt, a military aide to both Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. British science writer Stephen Baxter featured a world in which the Titanic didn’t sink in his 1998 short story “The Twelfth Album,” which features the retired ship as a floating hotel in Liverpool. In Baxter’s 2017 sequel to H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, The Massacre of Mankind (2017), Titanic survives thanks to acquired Martian technology.

That’s without mentioning thrillers and future history novels, such as Clive Cussler’s Raise the Titanic! (1976) and Arthur C. Clarke’s The Ghost from the Grand Banks (1990), featuring efforts to raise the sunken liner. Sea Lion Press, of course, has a Titanic novel of its own in the form of Timewreck Titanic (2017) by Rhys B. Davies, again involving time travel and ramifications to history when ships gathered for the centenary of the sinking arrive instead on the night in question.

Yet the Titanic story itself is full of “what if?” moments free from those works of fiction. Ones big and small, ways in which the tragedy that played out on an 882-foot stage in the North Atlantic might have never come to pass. Or, if nothing else, lessened the loss of life that April night.

To begin with, the Titanic could have set sail for New York sooner. Indeed, the maiden voyage had been announced by the White Star Line as leaving Southhampton on March 20, 1912. What changed that to mid-April was events involving her eventual captain, E.J. Smith, and her elder sister ship, the RMS Olympic. Six months before the sinking, on September 20, 1911, Olympic suffered a collision with the Royal Navy cruiser HMS Hawke. The damage to the Olympic, while not sinking her, was severe enough that she was obliged to return to the yards of shipbuilders Harland and Wolff in Belfast. Those repairs required six weeks’ worth of work and, as well as a later repair session in February 1912 following the loss of a propeller blade, diverted men and material from the still being completed Titanic. The earlier voyage might have avoided the massive patch of icebergs that flooded the Grand Banks area in mid-April, helping seal the Titanic‘s fate.

On the evening of the disaster, the Titanic‘s wireless operator, Jack Phillips, took down numerous ice warnings from other ships. While many of these made it to the bridge and the ship’s officers, at least one did not. Shocking as this might be to 2021 readers, in 1912 the wireless operators weren’t members of the crew but employees of the Marconi company operating more for passengers than in service of the ship as a whole. Sometime around 9:30 PM on April 14, Phillips took a message from the steamship Mesaba while passing on messages to the station at Cape Race, Newfoundland. It read:

Ice report: In latitude 42 N to 41.25 N, longitude 49 W to 50.3 W. Saw much heavy pack ice and great number of large icebergs, also field ice. Weather good, clear.

Stanley Adams, the wireless operator on the Mesaba, awaited confirmation of Phillips delivering the message to the bridge. It would never come as Phillips returned to Cape Race traffic. As the Titanic‘s most senior surviving officer, Charles Lightoller would write in his 1935 autobiography, the message never made it to the bridge. As the officer on the watch when the Mesaba‘s warning came through, Lightoller made clear what he would have done on BBC Radio in 1936:

Without a shadow of doubt, I should have slowed her down at once. That would have been imperative and sent for the captain. More than likely, in fact almost certainly, he would have stopped the ship altogether and waited for daylight to see his way through.

If Captain Smith had followed that course of action, he wouldn’t have been alone. Another ship in the Titanic story, and the center of controversy to this day, did just that. The Californian and her captain, Stanley Lord, were not to earn plaudits for their caution, sitting on the edge of the ice field. Instead, it became infamous for being, to quote the title of Leslie Reade’s 1993 book, the ship that stood still and seemed to have ignored the cries for help from the Titanic miles away but in apparent sight of the Californian.

Those cries for help being not wireless messages but rockets launched from the Titanic. Much has been said and written about what happened on and around the Titanic and the Californian that night. Without a doubt, more than this writer can hope to deal with here. What matters here, once again, are the actions of Jack Phillips. It was Phillips who, approximately a half-hour or so before the collision with the iceberg, had rebuked an attempted ice warning sent by its wireless operator, Cyril Evans. Phillips’ informing the man, “Keep out! Shut up, shut up! I am busy. I am working Cape Race,” led to Evans shutting down his radio for the night.

That silence appears to have coupled with indecision on the Californian‘s bridge, as junior officers on watch couldn’t seem to impart to a resting Captain Lord what they were seeing enough to bring him to the bridge. The result would give birth to two different narratives, flipsides of the same coin. On the one side, those who would condemn Lord in particular for his inability to act. On the flip side, those who have defended Lord and suggested everything from a third or fourth ship between the Titanic and Californian to freak weather effects affecting the Californian‘s perception of events. A debate which might not have come to pass if Phillips’ rebuke hadn’t sent Evans packing. Or perhaps if more decisive action on the bridge had led someone to wake Evans up. While it remains a sizable question if the Californian could have arrived in time to save anyone, it remains a lingering and compelling what-if from that night.

There are ramifications, too, beyond the sinking itself and the lives lost. The changes to maritime regulations, including the requirements for enough lifeboats and around-the-clock radio service, for example, saving countless lives in the decades that followed. How many of them would have lost without their enactment sooner than they might have been? Or would another disaster, one perhaps in the midst of or in the aftermath of the First World War, have still brought the changes eventually?

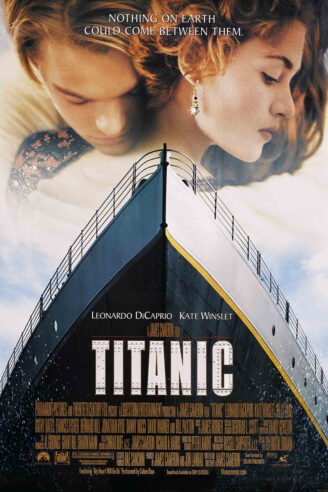

There’s also the pop culture reverberations, which started almost immediately. The first dramatic film version of the sinking was released within a month of the disaster (and starring survivor and silent movie star Dorothy Gibson). As the book Down with the Old Canoe (1996) and the 1998 documentary Beyond Titanic show, the sinking’s influence was far and wide even before James Cameron made it the subject matter of his immensely successful 1997 film.

Indeed, the ship also inadvertently inspired Cameron’s earlier film The Abyss (1989), when the writer-director watched a documentary on the underwater exploits of Robert Ballard, the man who led the American portion of the expedition that found the wreck site in 1985. Ballard’s opening-up of the undersea world with his explorations of the Titanic, and later still other lost ships, would inspire an ocean-based rush of science-fiction stories in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, ranging from Cameron’s The Abyss to the TV series SeaQuest DSV. All might not have happened without the Titanic‘s sinking as an inspiration for art and science alike.

Perhaps Walter Lord, writer of what may well be the definitive Titanic book, 1955’s A Night to Remember, said it best. Interviewed for A&E’s 1994 documentary Titanic: The Legend Lives On, the author said,

I still think about the might-have-beens of the Titanic. That’s what stirs me more than anything else. The things that happened that wouldn’t have happened if only one thing had gone better for her… If only comes up again and again, and they make the ship more than the experience of studying experience disaster. It becomes a haunting experience for me. It is a haunting experience of if only.

As Lord suggests, things could have been so much different one night in 1912. Those might have been moments spoke to countless writers and artists in the past and will continue to do so. For they, like the Titanic itself, will fascinate for as long as her story continues.

But they also reveal an intriguing paradox: the Titanic‘s place in history and culture was guaranteed by her tragic loss so early in its career. Without that, the Titanic would be another obscure ocean liner among others rather than the icon she has become.

An irony, perhaps, for those practitioners of alternate history to consider.

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history. Image on this page is of Titanic‘s sister ship RMS Olympic arriving in New York on June 21, 1911.