Eighteen years after the last flight of the Concorde, supersonic jets are making a comeback. United Airlines is buying fifteen planes from a new company, Boom, which would enter service later this decade. Flight times from London to New York would be cut in half.

There was a time when the future of flight was supersonic. After the first supersonic fighter jets joined the air fleets of NATO and the Soviet Union in the 1950s, British and French aircraft manufacturers started development of a supersonic passenger plane, which would culminate in the Concorde. Afraid of being eclipsed by their European rivals, Boeing and Lockheed put their own plans into motion, funded by the United States Congress. The Soviets couldn’t stay behind and eventually beat Concorde to the first faster-than-sound commercial flight in 1968 with the Tupolev Tu-144.

Little came of the American design efforts, and supersonic flights were banned over the continental United States due to loud sonic booms. Concorde was allowed to fly into Washington DC and New York, but by the time it was able to make frequent transatlantic crossings, competition from the Boeing 747 “Jumbo Jet”, which could seat four times the passengers of the previously-ubiquitous Boeing 707, meant there was no mass market for a supersonic airliner anymore. Rising oil prices didn’t help, and Concorde needed four times the fuel of the 747. Concorde became a plaything of the rich. In 1997, a round-trip from London to New York would set you back nearly $8,000, or $13,000 in today’s money; thirty times the price of the cheapest ticket available.

What doomed Concorde was the only fatal accident in its history: the 2000 crash at Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport in which all 109 passengers and crew were killed. Coming just before a general downtown in commercial aviation due to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, and after Airbus announced it would no longer supply replacement parts for the aircraft, it meant the end of the supersonic dream.

How different things had looked in the 1960s and 70s.

Bristol Type 223

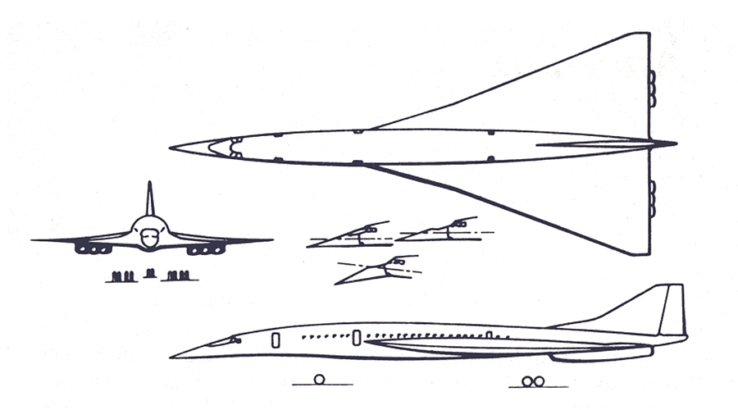

Before there was Concorde, British and French aircraft manufacturers were working separately on designs for a supersonic airliner. The work of the Bristol Aeroplane Company, now part of BAE, culminated in the Type 223, a transatlantic transport for about 100 passengers that would cruise at Mach 2. The main designer was Archibald Russell, who would go on to serve as vice-chairman of the joint Anglo-French Concorde Committee, working alongside Morien Morgan. Engineer’s Walk of Bristol has a thorough bio of the man.

Sud Aviation Super-Caravelle

This was the French design that went into Concorde. It was meant to be a supersonic version of the company’s successful Caravelle jet airliner, which could seat about eighty passengers and serviced its African and European routes.

North American NAC-60

North American Aviation, which later became part of Boeing, was the first to come out with a design for an American supersonic airliner: the NAC-60. It was a commercial adaptation of the company’s proposed nuclear-powered supersonic bomber, the XB-70 Valkyrie. (See America’s Atomic-Powered Aircraft)

It never left the drawing board.

Lockheed L-2000

In April 1960, Burt C. Monesmith, a vice president at Lockheed, told Popular Mechanics a supersonic passenger jet could be developed for $160 million. The following year, President John F. Kennedy committed the federal government to subsidizing 75 percent of the development of a commercial airliner to compete with Concorde.

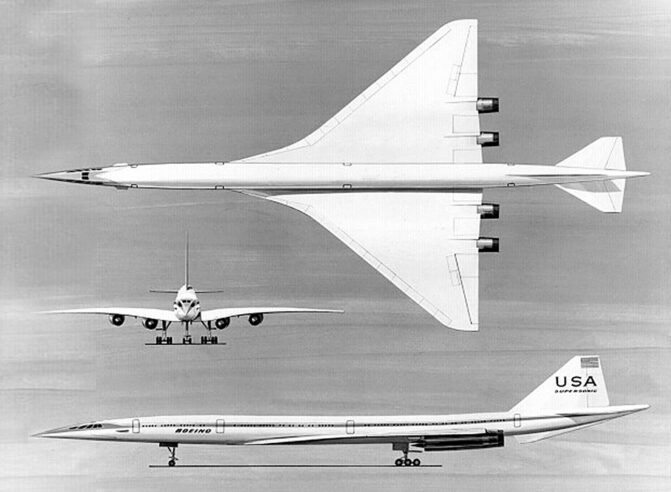

Lockheed applied for the money with the L-2000. It looked similar to Concorde, including the distinctive nose that could be drooped during takeoff and landing to give pilots more visibility, but it would be slightly larger, seating 170 (230 in later versions) instead of 100 passengers, and faster, flying at Mach 3.

Lockheed lost the contract to Boeing, whose 2707 was even larger.

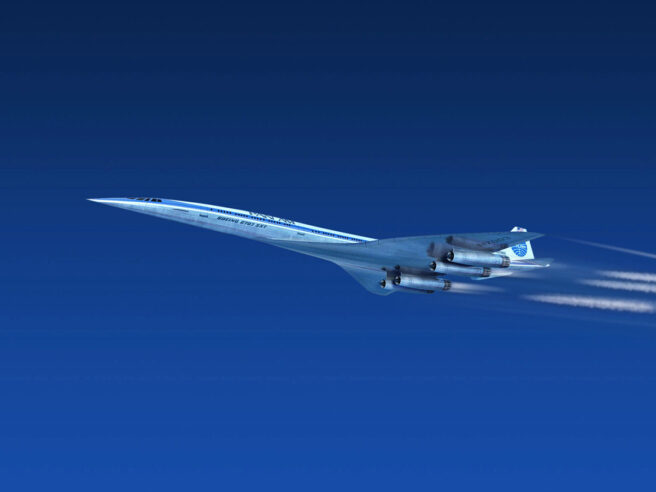

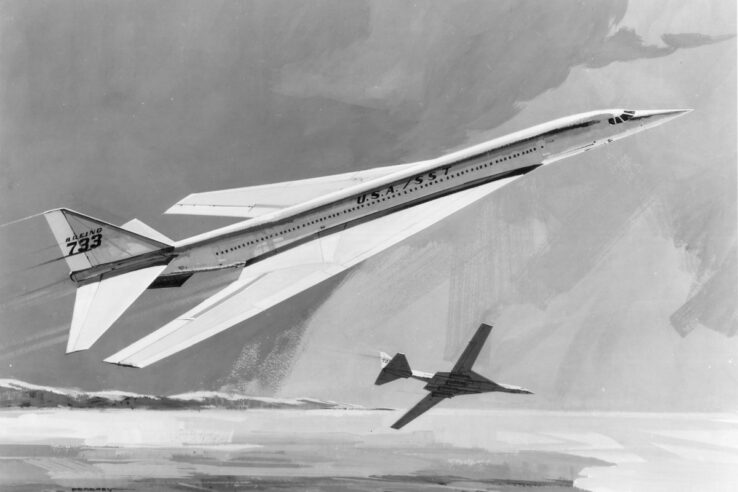

Boeing 2707

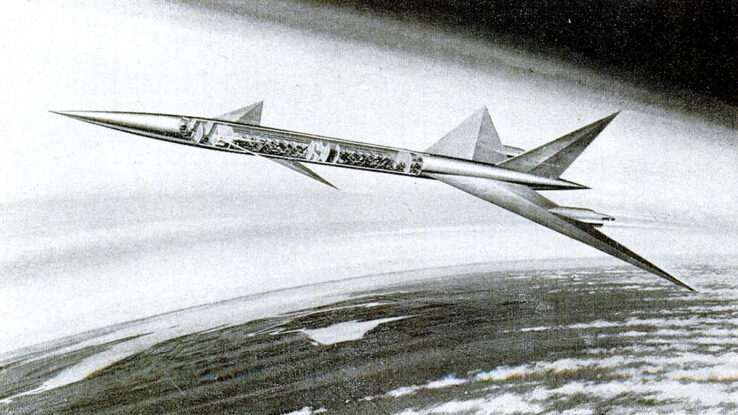

Boeing’s supersonic jet research started under the name Model 733 and became known publicly as the 2707. Like Lockheed’s L-2000, the 2707 would have flown at close to Mach 3, but it was much larger. In fact, it was one of the earliest wide-body aircraft designs, which would have allowed for a 2-3-2 row seating arrangement at its widest section.

The 2707 could accommodate almost 280 passengers, including thirty in first class, where every pair of seat would have its own television set; a luxury at the time.

Both Boeing and Lockheed built full-scale mockups of their designs in 1966. The former won the government’s favor, and Boeing expected the 2707’s maiden flight would be made in 1970.

But this was also the time of rising environmental awareness. In addition to noise pollution from sonic booms, it was feared supersonic jets contributed to the hole in the ozone layer. Although there was little evidence to support this, the United States banned supersonic flights over its territory and the government pulled funding from the 2707. That convinced Boeing to give it up altogether.

Douglas 2229

Douglas Aircraft, now part of Boeing as well, commissioned its own study into supersonic commercial flight independent of the government. Like the NAC-60, Model 2229 took its inspiration from the XB-70 supersonic bomber. It would seat about 100 passengers, but turned out to be heavier than the Boeing 2707, calling the economics of the aircraft into question.

Tupolev Tu-244

When the Soviets learned England and France were developing a supersonic passenger plane, they couldn’t stay behind. A supersonic jet, bigger and faster than Concorde, was rushed into production: the Tupolev Tu-144 could seat 150 passengers and travel at Mach 2.15. But speed came at a cost. The plane was unreliable, noisy and fuel-inefficient. When a Tu-144 crashed at the 1973 Paris Air Show, killing its six crew members as well as eight spectators on the ground, the Soviet supersonic dream fell with it.

Tupolev began work on a replacement in 1979, the Tu-244. It would have seated up to 300 passengers. The project was terminated soon after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In fiction

Dieselpunk fans will be familiar with the Concorde-esque Nazi supersonic jets in Amazon’s television adaption of Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (our review here). It looks similar to the real thing, except the cockpit windows are larger, the German plane’s tail is straight, not curved, and it has only two doors in the front whereas Concorde had two more in the back.

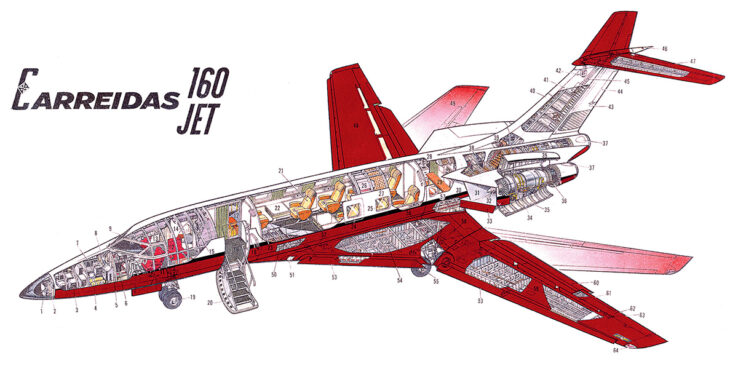

Tintin flies on board an experimental supersonic jet in Flight 714 to Sydney (1966-67) called the Carreidas 160, after its designer, millionaire Laszlo Carreidas. The plane wasn’t drawn by Tintin creator Hergé himself, but rather by Roger Leloup, who was also an aviation enthusiast.

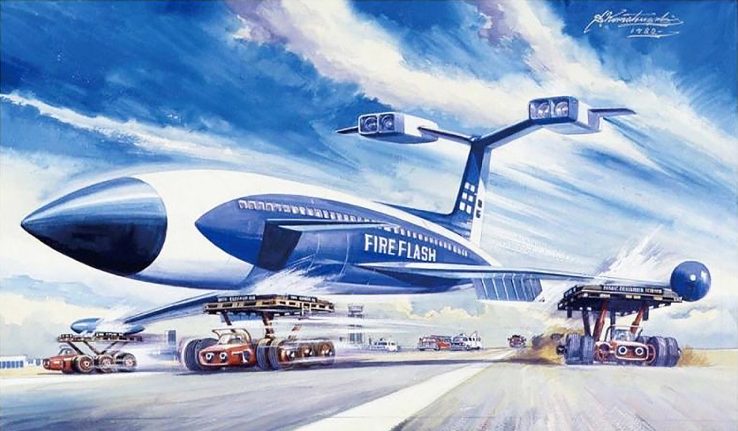

The 1960s marionette show Thunderbirds, set a century in the future, features various super- and hypersonic aircraft, notably the nuclear-powered Fireflash, which is capable of ferrying 600 passengers and crew around the world at six times the speed of sound. (See The Fabulous Vehicles of Thunderbirds)

The X-Men fly a supersonic jet modeled on the SR-71 Blackbird spy plane. Lockheed Martin, the Blackbird’s manufacturer, even has a post explaining how the fictional version measures up to the real one. In X-Men: First Class (2011), Hank McCoy, or “Beast”, is revealed to be one of Blackbird’s designers.

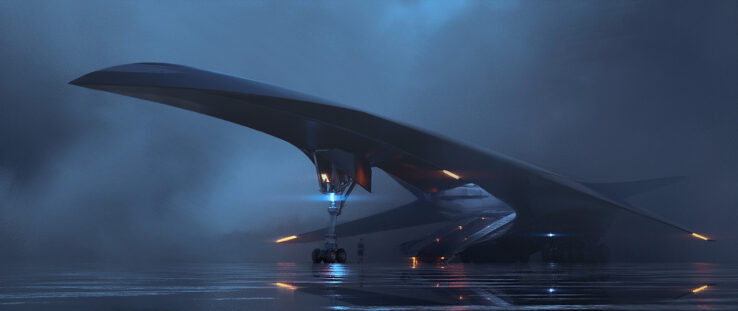

Artists Jozef Gatial, Maciej Rebisz, “etnf2” and “Mechagen” have released their own takes on the future of supersonic flight that never was:

2 Comments

Add YoursFirst of all, THANK YOU for this post. I absolutely love – LOVE – this site.

Not to be nitpicky, but it is burned into my puny brain that the Concorde actually crashed on July25, 2000. It resumed flight operations in November of 2001, to be retired finally in 2003. I know this for certain because I watched the story on the news (it actually was news back then) from my hotel in 2000, and I cried like a baby. No shame there. I was skeptically optimistic when operations resumed in 2001, but was hardly surprised in 2003 when the Concorde was finally retired. I toured an actual Concorde in Seattle at the Boeing museum in April 2004, and it felt like a funeral to me. So Concorde definitely crashed in 2000, and it was downed by no less than a DC-10 engine cowl piece. Either way, it has been permanently out of service since 2003, largely for the reasons you noted.

But other than this tiny bit, this article is a must-read. And have I mentioned that I love this site? Because I love it. THANK YOU again for all you do here.

Thank you so much, William! You’re right – I got the years mixed up. The crash was in 2000, the plane was retired in 2003. I’ll correct that in the article.

Happy reading!