Fog in Channel. Continent Cut Off

Apocryphal newspaper headline

In the first article of this series, I introduced the concept of geographical determinism: the idea that the destiny of a people or a nation is set by its geographical situation. We know that alternate history is dependent on contingency — the idea that the course of history can be changed, either by conscious action or by the confluence of events. How then might these two concepts be reconciled? How can a timeline explore a divergent historical while still remaining bound by geographical constants?

In this second article, I want to explore an example of geographical determinism close to many of our readers’ homes; that of Great Britain as an island nation. (I should stress that the scope of this article exclusively refers to the island of Great Britain and not to the United Kingdom or to the island of Ireland. This is primarily for reasons of length, as the inclusion of Ireland would considerably complicate the subject.) What has being an island meant for Britain, as a concept and as a practical endeavor? How has being an island driven the unification of the many British nations into what is (for now) a single unitary state? And finally, what, if we understand these geographic influences to be constants, are the possibilities for alternative Great Britains?

Island Britain

Great Britain is the largest of the European islands and the ninth-largest island in the world. No place in Great Britain is located more than 70 miles (113 kilometers) from the coast. The British coastline is characterized by a multitude of bays, headlands, peninsulas and smaller islands. Only the fjord-lined Norwegian coast or the islands of the Canadian Arctic provide a more fractured coastline.

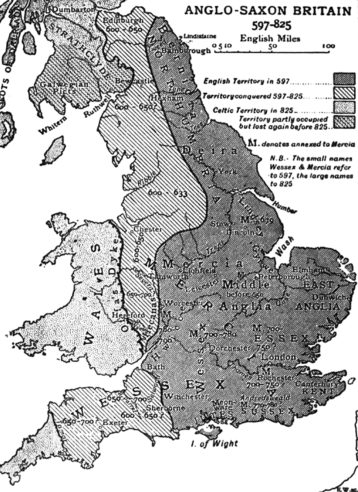

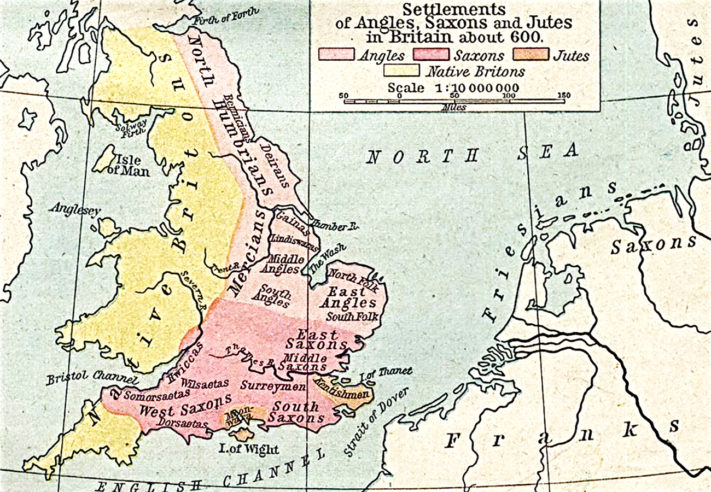

Being an island has arguably made the people of Britain different to their continental neighbors, just as it has significantly influenced the island’s history. The seas surrounding Britain delayed human reoccupation at the end of the last Ice Age; subsequently they would be a route for settlement and invasion. Historically Britain has been a target for seafaring peoples, most importantly the Germanic Angles, Saxons and Jutes, who crossed the North Sea during the Migration Period. Vikings from Scandinavia followed in their wake, raiding and conquering Anglo-Saxon settlements over the two centuries from 793.

In the first millennium AD, the seas around Britain were not a defensive moat but a vulnerability, and living far inland only offered false security. With their shallow draught longboats, Vikings could navigate up the many waterways of Britain to raid towns as far inland as Nottingham and Oxford. Britain’s long sinuous coastline offered a multitude of places for a would-be invader to make landfall.

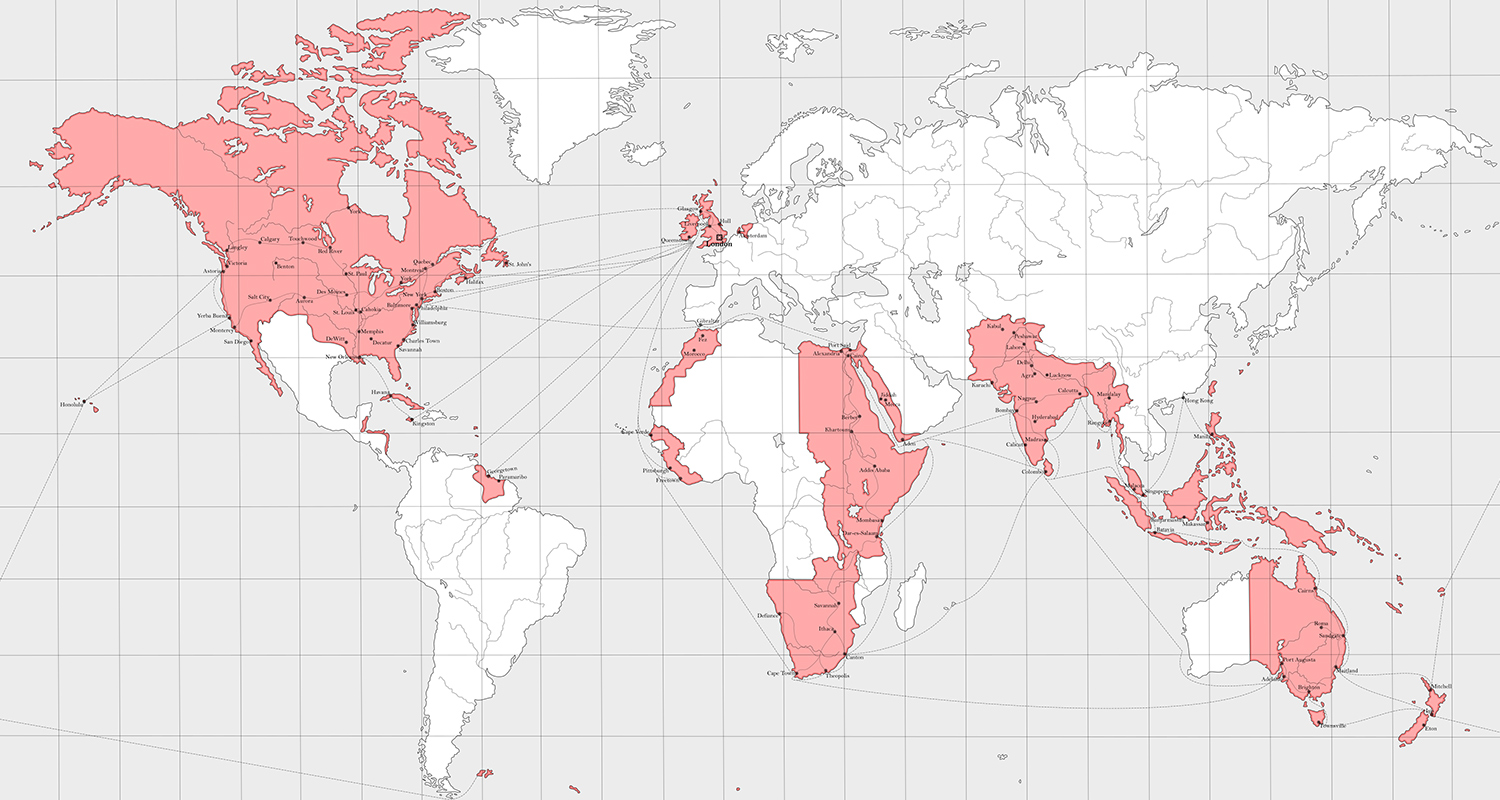

This vulnerability drove early British rulers first to unite and centralize the disparate peoples of the island and secondly to assert control over their own security. Since the time of Alfred the Great, successive British monarchs and governments have felt the need to organize navies, therein to turn the defensive vulnerability of the surrounding seas into a strength, which over the centuries might become projected further and further afield. Control of local seas and waterways was vital for British national security, and the building of the British Empire in later centuries only became possible as a direct result of Britain first asserting this control over her home waters.

Control of the North Sea would play a decisive role in the political power relationships of northwest Europe from the time of the Vikings onward, and after the First Anglo-Dutch War became a question of world politics. Britain’s geographic position, her relatively large coastal population and her extensive natural harbors all granted her prime position in this ever-growing struggle for supremacy.

Once secure behind a “wooden wall”, and with her internal frontiers dismantled, Britain had no need to maintain the large standing armies that drove continental arms races. There was no risk of Britain becoming a Prussian “army with a state”. This would arguably have consequences for the development of the British constitution into the modern era. How would British democracy have fared in times of crises given the opportunity for strong men to stage coups?

As well as danger, the seas around Britain were a source of opportunity. For communities living on the coastal fringes of Britain, away from the richer agricultural heartlands, fishing and coastal trade were vital supplements to sustenance and livelihood. Knowledge of the abundant cod fisheries of Newfoundland, most likely passed on by Breton fisherman, would have guided the first transatlantic explorers to depart from Bristol.

Sustained cross-Channel trade began with the Roman invasion of southern England. Before the development of good road networks, maritime trade on the North Sea connected the economies of northern Europe, Britain and Scandinavia with each other as well as to the economic hubs of the Baltic and the Mediterranean. Riches poured into English coastal settlements from the textile trade with the Burgundian Netherlands and from the wine trade with Gascony. Not only did these trade routes train generations of English sailors in the skills of seamanship, but the duty levied upon them helped to fund the English Crown in its campaigns of conquest and consolidation over the rest of the Britain.

The naval dominance that arose through struggles with France in the wars of the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, and which culminated in the Victorian Pax Britannica, brought Britain to global power.

Being an island nation might also have contributed to a sense of isolation, and of needing to be self-reliant. It could be argued that Britain’s island status is the cause for a long-standing semi-detached attitude toward continental affairs on the part of British governments — a legacy which stretches from Henry VIII to Salisbury and contentiously to the present day.

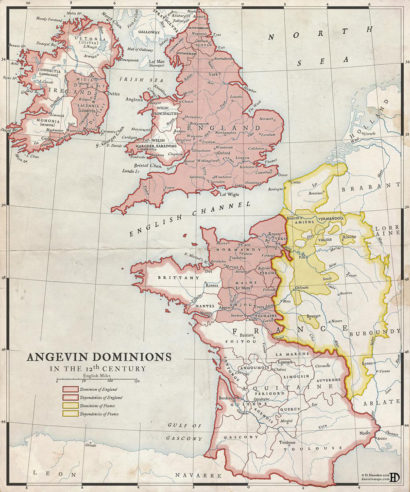

Conversely, strong cultural, economic and political links between Britain and continent, from the Angevin Empire to the EEC, would hint that it is much an insular political policy — the break with Rome and the rest of Catholic Europe — that is a greater cause for an “insular Britain” than anything as temporal as a coastline.

The influence of Britain’s island status can even be traced in modern-day cultural and geopolitical insecurity. A quick Google search immediately returns two news articles from the past decade which reference either “island Britain” or “a small island“. Both are in the context of British foreign policy; a contemporary anxiety which still echoes Dean Acheson’s statement (1962) that “Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role.”

Better together

The idea of Britain as both a single political entity and a geographic term goes back to classical times. The Greek Prettanikē became the Latin Britannia, supplanting the older name of Albion. Though Roman Britannia ultimately came to refer only to that portion of the island under direct Roman rule (excluding Caledonia), the name survives through medieval Welsh as Ynys Prydein — explicitly the island of Britain. Culturally, the idea of a single British state fell out of use in the Anglo-Saxon period before being revived as part of Stuart designs for the unification of the crowns of England and Scotland.

The term “Briton” had for a time come to mean only the native British Celtic-speaking inhabitants of the island. A revival of “Britannia” imagery began during the reign of Elizabeth I and when her cousin James VI, king of Scots, succeeded to the English throne, he attempted to invoke this imagery as part of a grander imperial design. James VI and I found his political plans blocked by both English and Scottish parliaments, and only through Royal Proclamation did he grant himself the style of “King of Great Britain”. There would be no Kingdom of Great Britain in law until a century later.

Idealism alone could not bring the kingdoms of Great Britain together. It was the need to unite against an external foe — and the convenient destruction of her primary Mercian rival by said foe — that led the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Wessex to unite England under her banner. The conquest of the last Brythonic British kingdoms — those of modern-day Wales — began under England’s Norman rulers and continued through to final Plantagenet conquest in 1283 and administration annexation into England in 1536. Attempts were also made by Plantagenet English kings to assert their overlordship of Scotland, extending to attempts at outright conquest under Edward I.

Conquest of her Celtic neighbors served a useful military purpose for medieval England: it secured her borders against invasion backed by continental powers (notably the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France). It also eliminated potential staging grounds for pretenders to the English throne. Further it provided marcher lordships (as in Wales) and confiscated land which could be distributed to loyal supporters.

It could be argued that these strategic risks and opportunities would always exist for so long as the island of Britain is divided between unequal powers. With England possessing the greater population, wealth and arable land, was she not always destined to gain the upper hand over her rivals, and to unite Britain under her lead?

What might have been?

Heptarchy in the UK

A united England came into being relatively late in history — nearly 500 years after the first Anglo-Saxon invasions of post-Roman Britain. For much of those 500 years, a rough balance of power prevailed, with first Northumbrian ascendancy, followed by the rise to power of Mercia, and finally with Wessex assuming leadership in the struggle for survival against Viking rule.

What if, in the absence of a Viking Age — say the Franks are never unified into Charlemagne’s empire and the richer coasts of Flanders and the Seine Valley remain the Norsemen’s preferred soft target — there is no external driver for English unification?

An “England” that remains a collection of smaller independent kingdoms might never rise to dominate her Celtic neighbors. Similarly, she might never have the centralized government required to both organize and pay for a large navy. Under such circumstances, “England” is likely to be the nation invaded and ruled by foreign powers. Like medieval Italy, she might spend much of history neither independent or united.

Henry succeeds or Lancaster bombs?

Many of England’s medieval kings ruled with their feet on either side of the English Channel. Prominent among these were the Angevin kings — Henry II, Richard I and John — whose territory at its height included huge swathes of modern France. A century later, Henry V of England won considerable victories that almost led to him being crowned Henri II of France, but for an unfortunate death by dysentery.

From the start of the Viking Age until the loss of Calais in 1558, a succession of polities and kings straddled lands in both island Britain and continental Europe. During this time there was never an exclusively unique, or an entirely exclusive, “British” nation.

Unlike the relatively straightforward union of the crowns between England and Scotland, a prolonged English dominion in France — by which the English king was nominally a vassal of the French king — might have entangled England in the complexities of European politics for good. Indeed, a developing “nation” that contained large parts of modern France, or even an Anglo-French union of the crowns, would likely have seen its political center of gravity pulled south. Medieval France had a population of seventeen million in 1300, compared to only three million for England and Wales and 400,000 for Scotland. France was also the richer nation, on account of her greater agricultural potential in the pre-modern era.

The power disparities that our timeline saw between England and Scotland would have been far greater in an Anglo-French union, and with England the junior partner. In such a scenario, it is possible to see Paris being carelessly indifferent to the security of the distant Welsh or Scottish borders — the Rhine and Alps would be far more pressing frontiers. Far more likely than a united Britain would be the breakaway of more distant “English” lordships, either to form a reborn Kingdom of Northumberland or else to join with lowland Scotland.

In our history, the prospect of Scottish border raids was sufficient to restrict the movements of English kings in their French campaigns — as alluded to in the opening scenes of Shakespeare’s Henry V. In this scenario, the situation is reversed: the military demands of the continent would reduce the means and motivation to launch wars of conquest in the far north.

An England that remains entangled in some cross-Channel union is unlikely to be able to extricate itself so totally from European affairs as the England of our timeline’s Henry VIII. Similarly, it is far less likely to have the free hand necessary to unite the British Islands under a single banner.

The Stuart secession

That our timeline’s union of the crowns occurred as it did is something of a historical fluke. A surviving Tudor lineage from either of Henry VII’s two sons (Arthur Tudor died after Margaret Tudor’s marriage to James IV of Scotland was arranged) would have prevented it entirely. In the short term, the union caused turmoil and ill-feeling between the two nations, but it was ultimately replicated at a constitutional level in the Act of Union a century later.

The Act of Union was a cold-minded practical measure on the part of the English Parliament. No appeal to romantic imperial notions could persuade either parliament of the benefit of union a century before, but the eventual prospect of a newly independent Scotland on the death of Queen Anne forced the situation in the interests of permanent legal union.

The English Act of Settlement of 1701 had decided the future line of succession to the English throne by limiting it to Protestants only, and had done so without the English Parliament consulting its Scottish counterpart. In retaliation, the Scottish Parliament passed the Act of Security (1704), which made provisions for Scotland to choose her own heir — potentially one different to the English choice unless certain economic, political and religious conditions were agreed first. In practice, this threatened the end of the union of the crowns.

An independent Scotland, it was feared, would be a threat to England’s military security — much as it had been previously in history — and a complication to her commerce. After a lot of legislative back and forth between the two parliaments, and a fair amount of English threats and bribery, the Act of Union merged the two kingdoms into one: the Kingdom of Great Britain.

But what if the union had ended here, with Scotland selecting her own monarch? The Act of Security specifically required a Protestant candidate, ruling out an immediate Stuart Restoration, but continental Europe offered an abundance of German princes. The economic consequences for Scottish trade would have been dire, and for England too the rise the global power of the historical eighteenth century might have been stillborn. Perhaps the two nations were better together after all?

Seeing through the fog

Being an island nation has driven a significant part of Great Britain’s destiny — the rise to naval power, an economy tied to trade and the sea, the need to unite against seaborne threats — but none of these outcomes need be inevitable. There is a certain multiplier effect at work in British unification: the consolidation of power into a single state allows that state to fully marshal the benefits of its island situation. A Britain that still had major internal frontiers could never Rule the Waves, much less project power onto the continent or elsewhere.

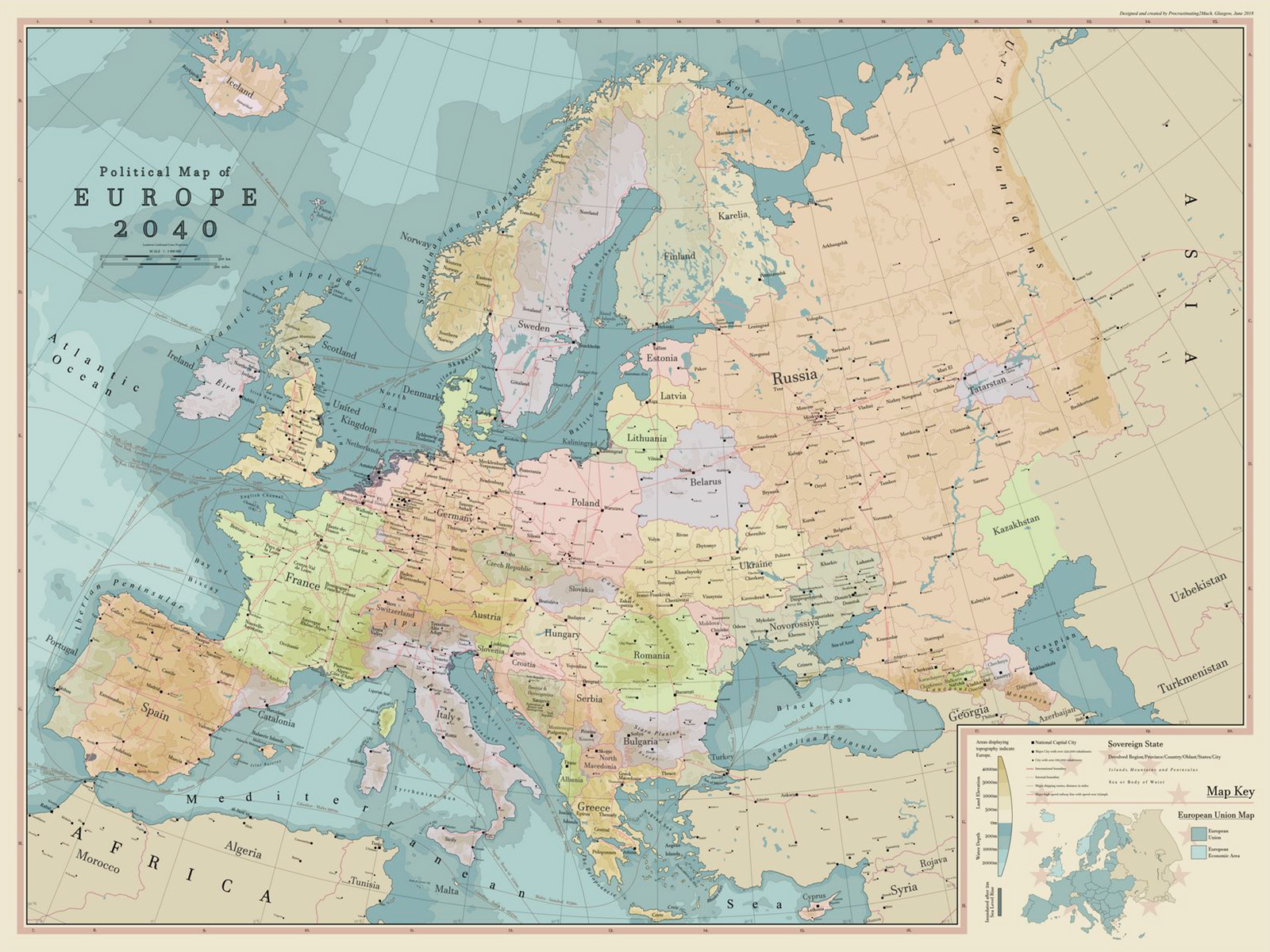

But the rise of a single British state, a unitary “island nation”, is far from inevitable. As discussed, there are many scenarios in which the island of Great Britain is host to multiple independent nations and where “Great Britain” is not an Olympic Team but merely a geographical term. In a sense, the UK of our timeline is lucky that she has mostly natural borders.

What are “natural borders”? Well it’s funny you should ask…

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.