In this great chain of causes and effects, no single fact can be considered in isolation.

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859)

Alternate history is all about contingency. In layman’s terms, asking “what if?”

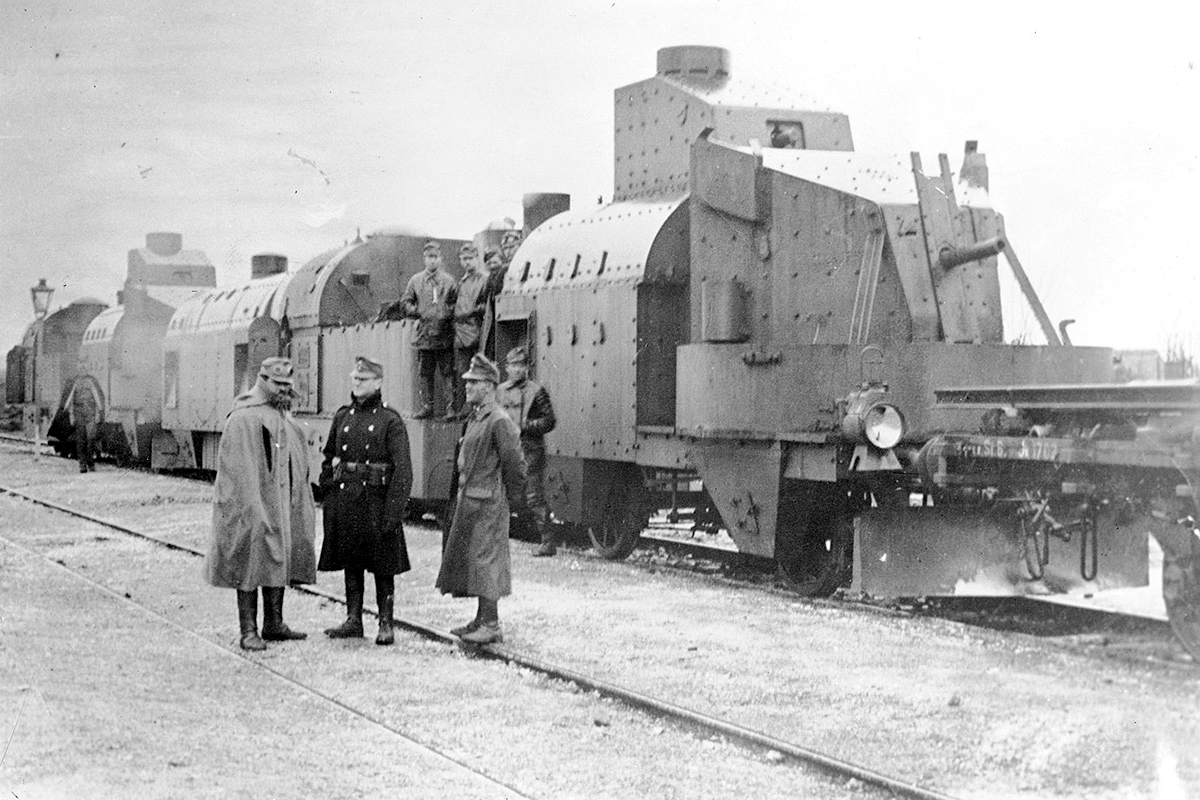

We look at what did happen historically and we ask “what if it had happened differently?” What if a certain famous battle had been won by the other side? What if a famous statesmen or politician had never been born? What if a great empire had never risen? When we ask these questions we instinctively understand the notions of cause and effect — one event drives another; actions have consequences. What happens in history is contingent upon what events happened before.

If you change the past, you change the future.

Alternate history is a rejection of historical determinism. For it to be possible for events to have occurred differently to those in our own timeline, history cannot be predetermined. If you set your point-of-divergence back far enough, nothing in history is inevitable.

But what if some things are? What if certain circumstances in history actually do make certain outcomes inevitable, or at least highly likely? How might the deck be stacked in favor of our timeline, and what does this mean for alternate history and for the stories and timelines we want to write?

In this series of articles I’ll be exploring the concept of geographical determinism as it can be applied to alternate history — and specifically how physical geography influences the course of history.

Geographical determinism

What is geographical determinism?

Put broadly, it is the idea that human habits, societies and cultures are shaped by their geographic conditions. At its most basic, it holds that human activity is dependent on the physical environment in which it is set and that human action occurs as a response to the natural environment — much in the same way that any other species reacts to environmental factors or to the opportunities or dangers of their habitat.

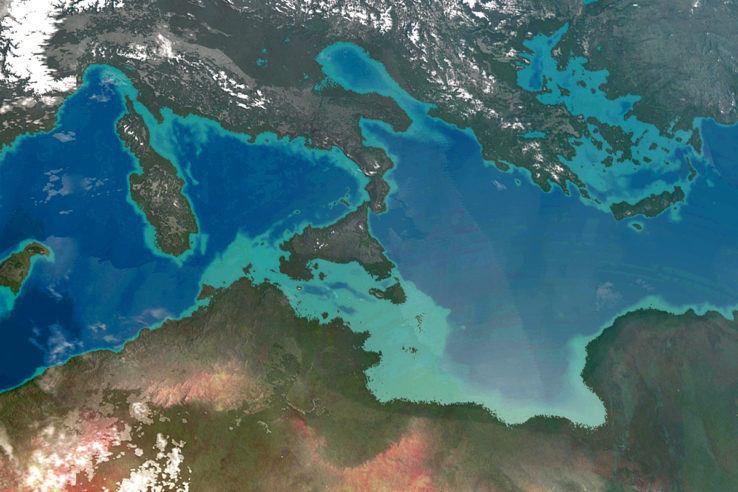

A geographical determinist might argue that a society living on a island or along a coastline in possession of a great number of natural harbors would be more inclined to become a seafaring people, and in turn to engage widely in exploration and trade with the outside world. An inland or continental society might instead become more closed off and defensive. Broad plains and wide river valleys might become home to expansive empires or to large centralized states with high tightly organized populations, while fragmented upland landscapes will be characterized by smaller, more independent communities.

Geographical determinism will probably be most familiar to the modern alternate-history community through Jared Diamond and his book Guns, Germs, and Steel (1997). Jared ran with the idea that environmental differences between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres, in turn arising from physical geography, were the route cause for ultimately allowing Eurasian civilizations to survive and to conquer the rest of the world in the centuries leading up to the modern era.

The idea that one initial set of circumstances can drive a string of consequences to a particular outcome is far from an alien idea to an alternate historian. But ought those initial circumstances always lead to the same outcome? Just how deterministic is geography, and what does this mean for alternate history?

As an idea, geographical determinism has a long pedigree. Is the geographic position of Athens why that city was ascendant over her Greek rivals? The classical philosophers Xenophon and Thucydides believed so.

Centuries later, the Roman Strabo made the same argument about the city of Rome.

Aristotle argued that climate was a driver for fundamental differences in temperament between Europeans and Asians — a line of thought carried through as a central thread in European essentialism up to the modern era. Cooler harsher climates were supposed to lend their inhabitants courage, industriousness and morality. The tropics, however, bred idleness and insolence. According to these particular Europeans, anyway.

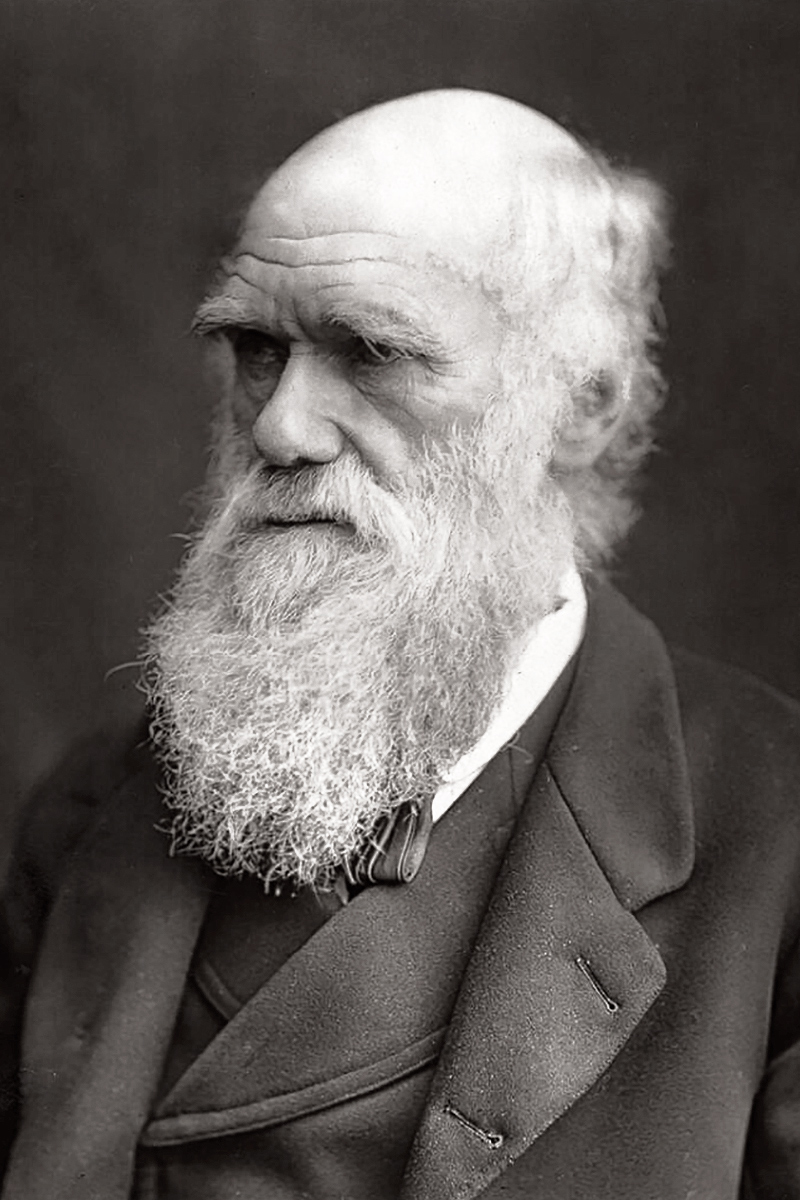

Darwinism

While early ideas around geographical determinism relied upon a theological or even teleological framework (the argument that the purpose of a thing explains its existence; that things come about because of what they could do), it was Charles Darwin whose theories first provided a scientific basis from which it could be demonstrated that humanity was intrinsically tied to its natural environment. In evolution and natural selection, geographical determinism was given the mechanisms by which it could be advanced as a natural law.

Building upon Darwin’s work in the late nineteenth century, geographical determinism enjoyed a strong revival under the German geographer Friedrich Ratzel. Ratzel observed that the nature of human interaction with the environment varied between cultures, and he called for historical analysis of the links between history and geography.

Geographical determinism was further popularized in the twentieth century by the prominent American geographer Ellen Churchill Semple in her publications History and its Geographic Condition (1903) and Influences of the Geographic Environment (1911).

But as so often happened with the scientific and philosophical developments of the nineteenth century, geographical determinism also became used as a tool to justify colonialism and imperialism. As a theory which appeared to provide a pseudo-scientific explanation for the supremacy of white European races, it was inevitably drawn upon to apply stereotypes across entire populations.

Encumbered with this racial baggage, it’s not surprising that “classical” geographical determinism should have faded away from a position of academic orthodoxy over the twentieth century. For the most part it has been supplanted in this role by the counter-theory of Possibilism — the idea that while the environment sets constraints, human culture is primarily determined by social conditions.

It has revived — somewhat — over the last few decades, in a new form, what might be termed “neo-geographical determinism”. In this, there’s been a fresh examination of how physical environments can push (but not compel) societies and states toward certain paths in their economic and political development.

As climate change has become a more widely understood crisis, there has also been more serious examination of how ecological force can nurture or limit the development of a civilization. Looking forward to the second half of the twenty-first century, it seems likely that geography will make or seal the fate of many millions of people across the globe.

Inevitability

To an alternate historian, the idea that a particular outcome is inevitable — quite literally set in stone in the case of mountain ranges — is rather unwelcome. If the United States is always to become a continent-spanning superpower, or China a single centralized and homogeneous nation-state, then where lies the potential for meaningful divergence?

In the original performance of “Rule Britannia,” the invocation of Britain to “rule the waves” was entirely aspirational. The overwhelming British naval dominance of the following century had yet to come into being. But does Britain’s literally insular nature make the rise of a naval power inevitable? Before that, does it also make inevitable the rise of a single dominant nation within the islands of Northwestern Europe?

This creates a problem for alternate history. We like to think our scenarios and timelines, the settings for our stories, are reasoned out divergences from history as it happened. As the community has developed over the last few decades, a high bar has been set for plausibility. If fixed geographic conditions make inevitable certain historical outcomes, does that limit our range for plausible alternate history scenarios? How might we develop interesting new scenarios which take account of these geographic conditions while allowing for worldbuilding that is both divergent and plausible within those original conditions?

Alternative Earths

A staple of old clichéd alternate-history maps was the “space-filling empire” — a vague superstate that took up a large, typically continental-sized portion of the world map, which the author either didn’t know or didn’t care to know enough to flesh out. The converse cliché was Balkanization of a larger state from our timeline being split into its constituent parts — statelets and micro-nations that on a level of plausibility would be of questionable economic or political viability. Of course, the political map of our timeline knows and has known both micro-states and continent-spanning powers. These aren’t implausible in themselves. The key is determining what geographic factors make these types of polities more or less likely.

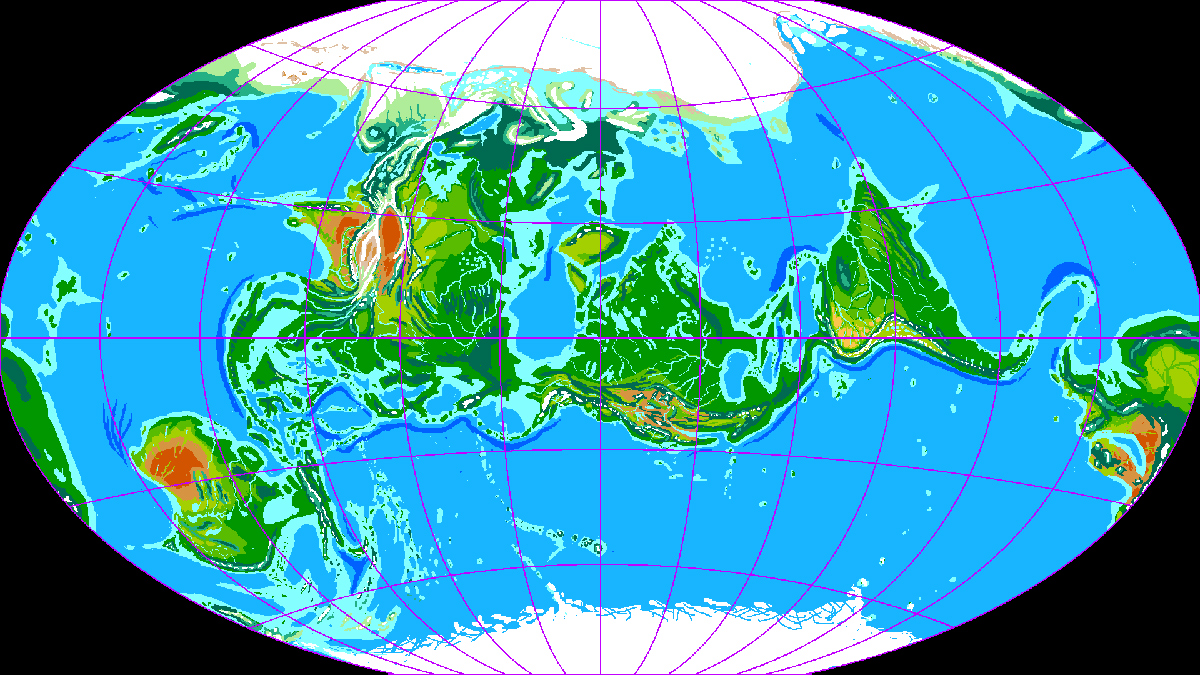

A rather extreme solution to the limits of geography was proposed many years ago by Chris Wayan in his design of Jaredia, an Earth-analogue tilted about on its axis to create a single continuous east-west corridor of land along the equator. The result is an exploration of Jared Diamond’s thesis, and is beautiful as a work of design, as a though experiment, and as an attempt at worldbuilding.

I would argue that we don’t quite need to alter the Earth’s axial tilt to create more recognizable alternative Earths.

One of my favourite works of popular science is Stephen Jay Gould’s Wonderful Life. Readers who are familiar with the 1946 film that title references will immediately recognize one of the book’s main themes: the idea that history might not have followed the same path that it did. Gould looks not to human history, but to the evolutionary history of life itself. His subject is the Burgess Shale, a fossil-rich shale deposit from some 505 million years ago — as close to a year zero as any in reference to the history of life on Earth. This one fossil bed contains a wider diversity of basic anatomical body plans than exists across all of Earth today; evidence of a time of major evolutionary experimentation, but one from which few prototypes left descendant forms.

How does this apply to geography? Gould reasoned that while the earliest forms of life on Earth represented the original conditions for evolutionary history, they by no means set as inevitable that which followed. Contingency always has a role to play, even within what feel like iron laws of nature. Biology, just like geography, might endow a particular species or nation with apparent advantages, but there can be no guarantee that those advantages will last or be applicable in all circumstances. A highly specialized feeding system means nothing for “survival of the fittest” on the day of an asteroid impact. Likewise, a perfect natural harbor is susceptible to a slow death by silt, and an invasion can destroy in a day a centuries-old irrigation system.

Geographical determinism then can be seen not as a straitjacket, but as a set of guide-rails. Sometimes providence does indeed favor one nation over another. Sometimes however, history goes completely off the rails.

Final word

While it is true that geography sets the stage upon which history plays out, it is less clear that it writes the script. The concept of geographical determinism appears at first glance fundamentally opposed to the possibility for historical contingency, at least in any way which might allow for greatly divergence timelines. In reality, it can be a strong influence on a timeline, but by no means the final word.

A good alternate-history setting understands the limits that geography sets and works with these in either writing a timeline or in telling a good story. There will always remain a place for contingency in history, and “events” can overturn whatever favorable advantages seem fixed from the start.

What favorable advantages might these be? Well, for starters, how about the Channel of open water that separates the nations of Britain from those of continental Europe? What divergent paths exist for this insular constant?

Find out in the next article in this series.

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.