Norman Bel Geddes was an American industrial designer and futurist who had a major influence on the streamlined Art Deco design of the 1930s and 40s.

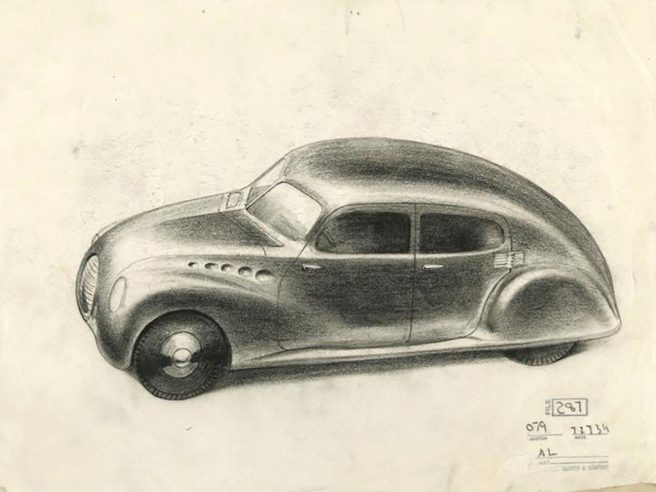

Geddes started out as a theater set designer before opening his own industrial design studio in 1927. His early work included such consumer products as cocktail shakers and radio cabinets. He quickly moved on to more ambitious projects, including a teardrop-shaped car and the amphibian Airliner Number 4.

Cars

Unimpressed with the cars of his time, which he found unsightly and aerodynamically inefficient, Geddes came up with his designs, which still look unconventional today.

Graham-Paige

In 1928, Geddes convinced the Graham-Paige Motor Company to hire him to design their futuristic 1933 Roadster. Geddes worked backwards from that design year by year to allow the company to incrementally work toward his radical vision.

Geddes’ contract was terminated after the stock market crash of 1929, and Graham-Paige did not far well during the Great Depression. But the work had established Geddes’ reputation as a designer.

Ukrainian State Theater

Geddes joined the 1930 competition to build the Ukrainian State Theater in Kharkiv with a design that incorporated three auditoriums: an indoor one seating 4,000; an open-air one seating 2,000; and one for mass meetings with a stage for 5,000 actors and 60,000 audience members.

The design included an underground parking garage with space for 650 cars — at a time when there were hardly any cars in Kharkiv at all.

Three Americans — Eric Engerder, Alfred Kestner and Carl Meyer — shared the first prize with German and Ukrainian competitors. Geddes was awarded the second prize worth just $770.

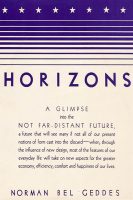

Horizons

Geddes published Horizons in 1932, in which he articulated his ideas on automobile design. He argued that the engines should drive the car from the rear, that drivers should sit up front and center for a commanding view of the road, and that cars should ride on six or eight wheels instead of four.

Not all of these ideas were influential, but the book, and Geddes’ work, helped popularize streamline in industrial design.

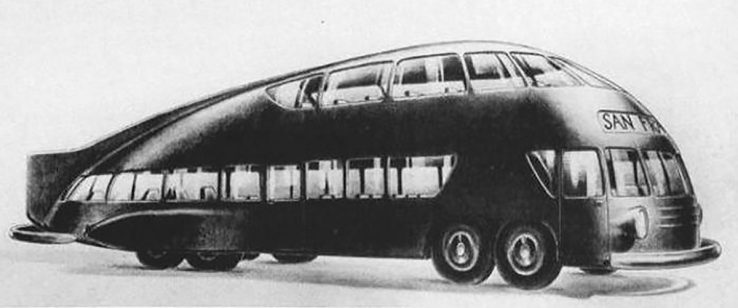

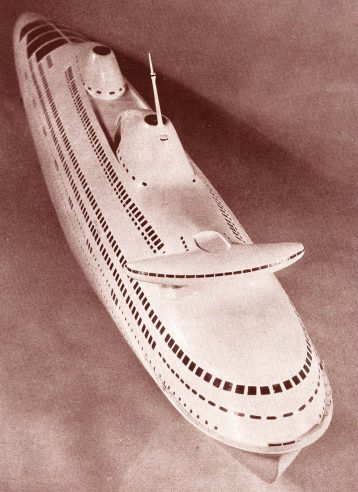

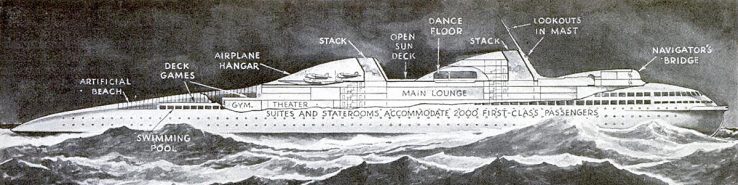

Ocean Liner

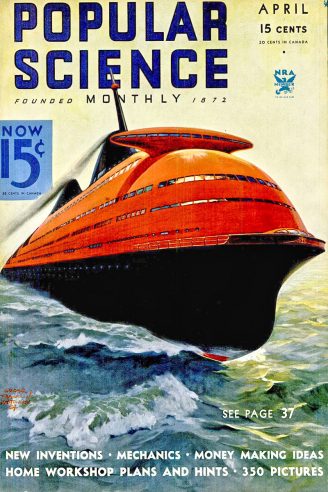

One of the designs in Horizons was a 330-meter-long ocean liner, shaped like a cigar. Lifeboats, sundecks and walkways were all tucked away behind the ship’s streamlined facade. In good weather, transparent parts of the skin would slide back to expose recreational areas. The only protruding part of the design was the bridge, which was swept back like a monoplane wing in order to reduce wind resistance.

Popular Science and Popular Mechanics both wrote stories about the ship. The former included a cutaway in its April 1934 edition.

Geddes declined an offer to sell the design to Italian dictator Benito Mussolini for $200,000, hoping for an American buyer. There never was one.

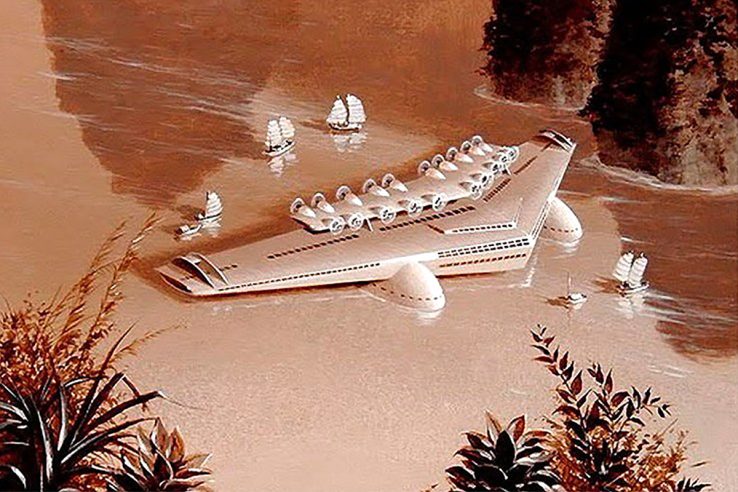

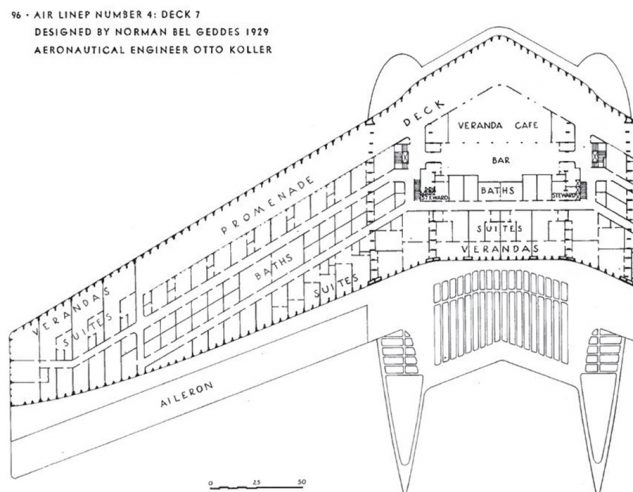

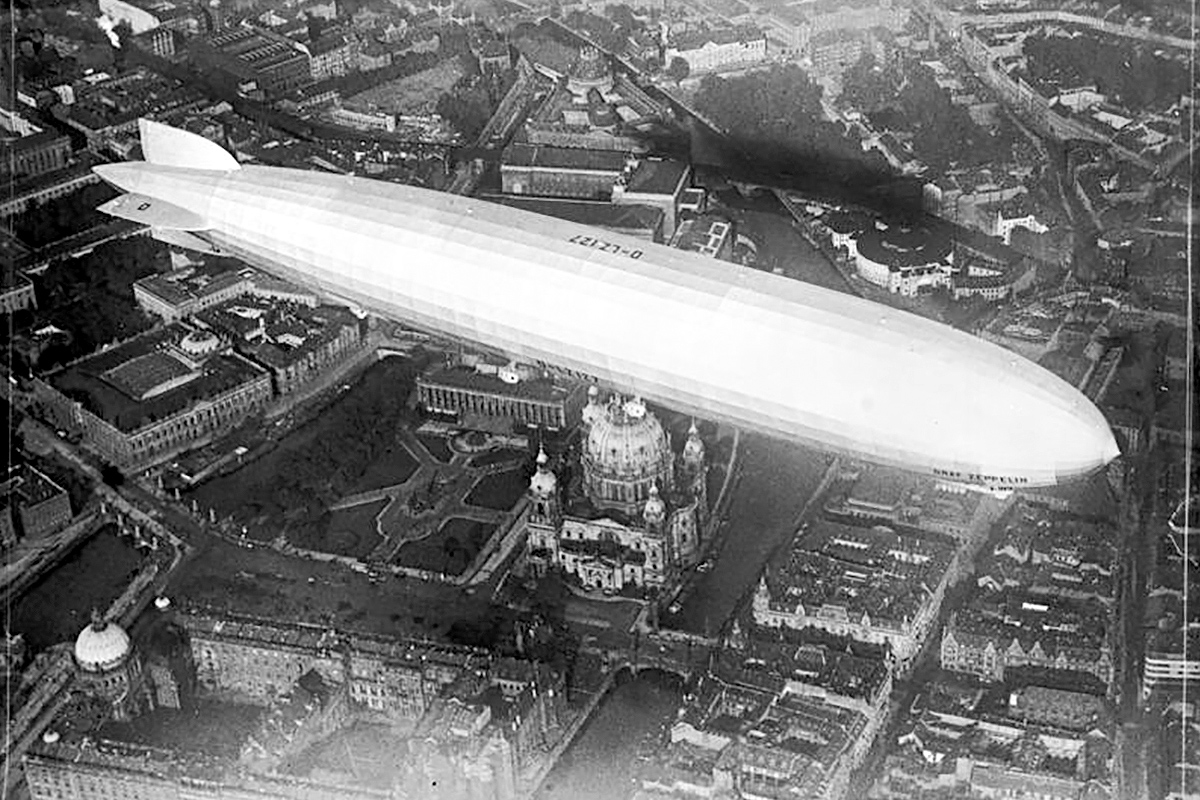

Airliner Number 4

Also published in Horizons was the “Airliner Number 4”, a mammoth airship inspired by Germany’s Dornier Do X flying boat. Geddes wanted to seat up to 600 people and provide areas for concerts, deck games, a gymnasium, a solarium — even two airplane hangars!

He put the cost of building the aircraft at $9 million, which would be something like $125 million in today’s money.

Click here to learn more about Norman Bel Geddes’ fantastical airliner.

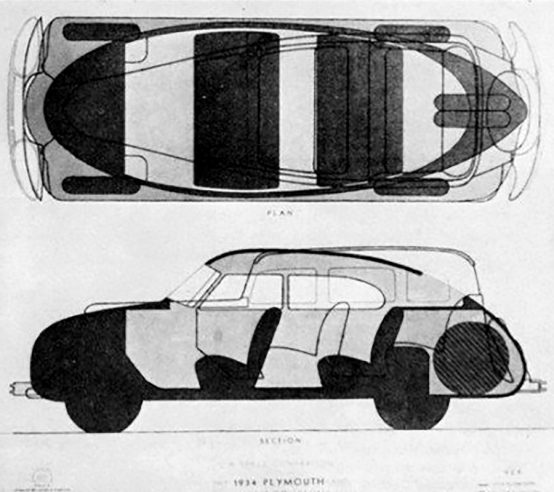

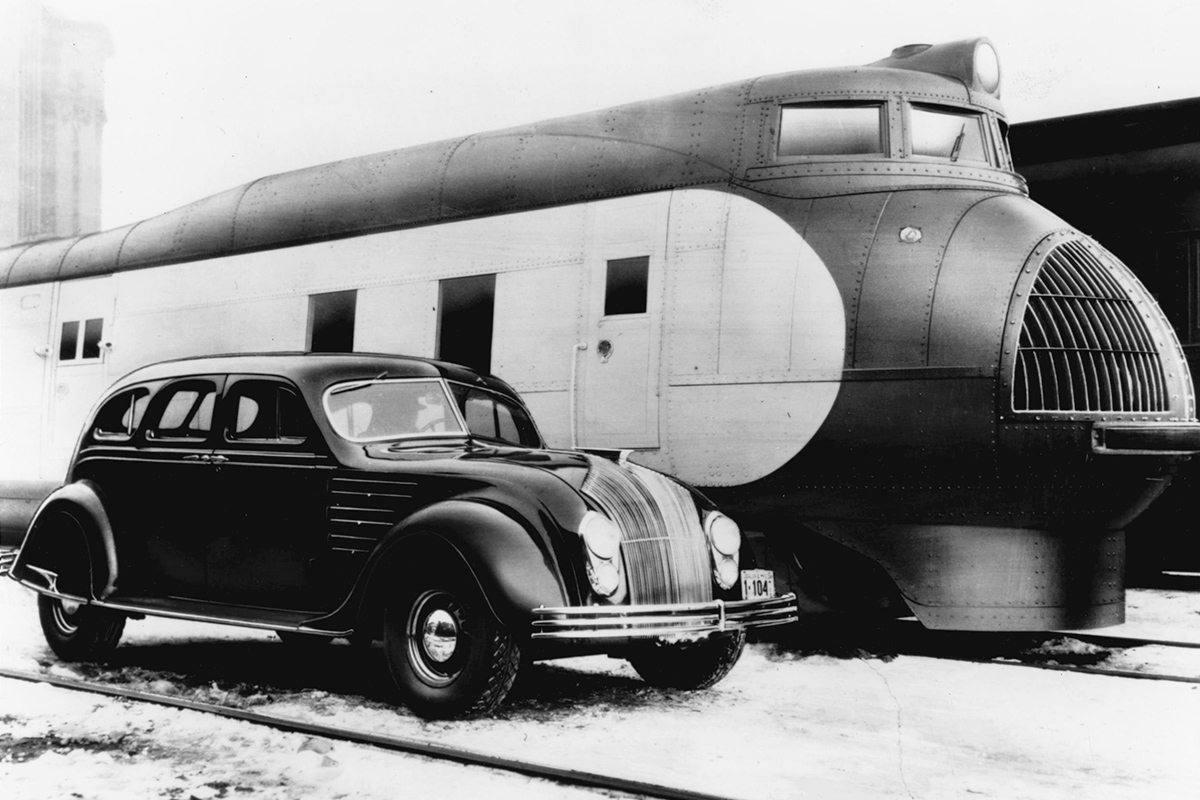

Chrysler

Horizons brought Geddes to the attention of Walter P. Chrysler, whose company hired him to shrink and streamline the 1933 Plymouth, so it would be easier (and cheaper) to transport.

Geddes also contributed to the design of the Airflow, which was the first mass-produced streamlined car. Geddes gave the 1935 model a new hood, which extended forward to a V-shaped grille. He also added decorative hood louvers. It was to no avail — the Airflow’s design was still too unconventional for its time and sales were lackluster.

Texaco Doodlebug

Texaco hired Geddes, along with fellow industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague, to modernize the company’s brand. They came up with the famous red T-star and block-letter logo that is still in use today. They also styled the architecture and color scheme of Texaco’s petrol stations — and its trucks.

The Doodlebug was a revolution in design. It had no fenders. The conventional hood was gone. It used curved side glass and a compound-curved windshield. This wouldn’t see mass production for another two decades. The truck’s shape altogether differentiated it from the boxy designs of its time.

Perhaps most unusual was the Doodlebug’s height: just 6 feet, or 1.8 meters. That made it barely taller than a 1934 Ford sedan!

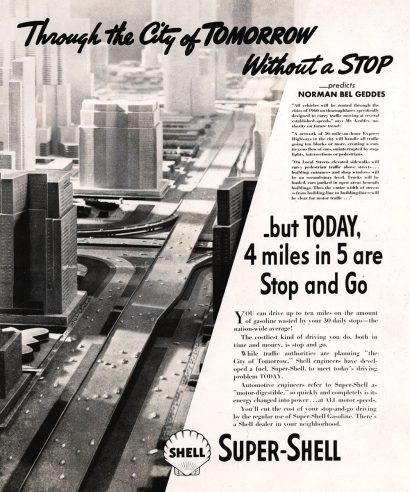

City of Tomorrow

In 1937, Geddes approaches Shell Oil with an idea for the highways of the future. This led to the “City of Tomorrow” campaign, in which Geddes predicted that, by 1960, all traffic would be routed through cities on thoroughfares “specifically designed to carry traffic moving at several established speeds.”

A network of 50-mile-an-hour Express Highways in the city will handle all traffic going ten blocks or more, creating a continuous flow of cars, uninterrupted by stoplights, intersections or pedestrians.

Geddes would later write in Magic Motorways (1940) that “there should be no more reason for a motorist who is passing through a city to slow down than there is for an airplane which is passing over it.” Postwar urban planners took his advice to heart and demolished entire inner cities to make room for highways in what is now considered to have been a colossal mistake.

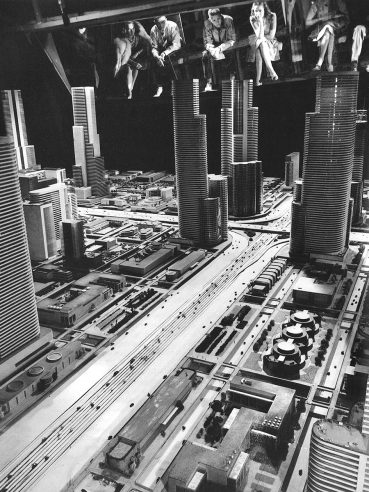

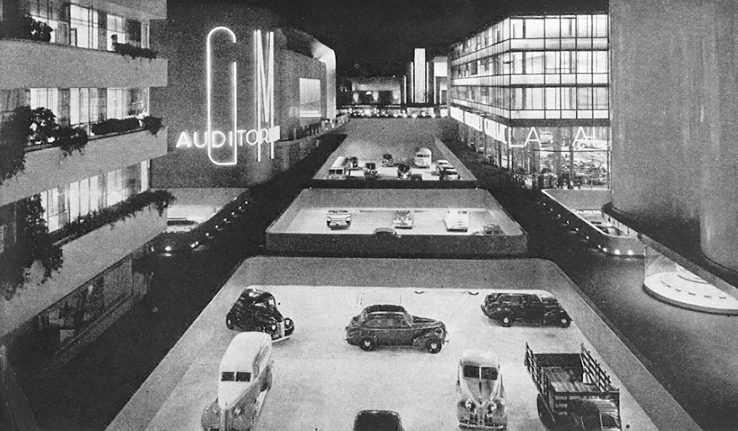

Futurama

Geddes had no luck selling his ideas to Chrysler, Goodyear or General Motors — until he secured a meeting with the big men of GM: Alfred P. Sloan Jr., William S. Knudsen and Richard H. Grant. Knudsen and Grant were not impressed, but Sloan liked Geddes’ futuristic ideas and hired him to design the company’s Futurama exhibit for the 1939-40 World’s Fair in New York. It would become the biggest success of Geddes’ life.

Originally given $2 million to built the exhibit, Geddes convinced GM to raise the budget to $7 million. He hired 3,000 workmen to build a vast animated model of his vision for America. It consisted of half a million buildings, one million trees and approximately 50,000 cars, 10,000 of which traveled along a fourteen-lane multi-speed highway.

Futurama was the most popular exhibit at the fair by far, receiving over a million visitors during its two-year run. At a time when America was still recovering from the Great Depression, it gave ordinary people a glimpse of a better life.

Legacy

Geddes returned to theater design after the Second World War and died in 1958. But his legacy lived on.

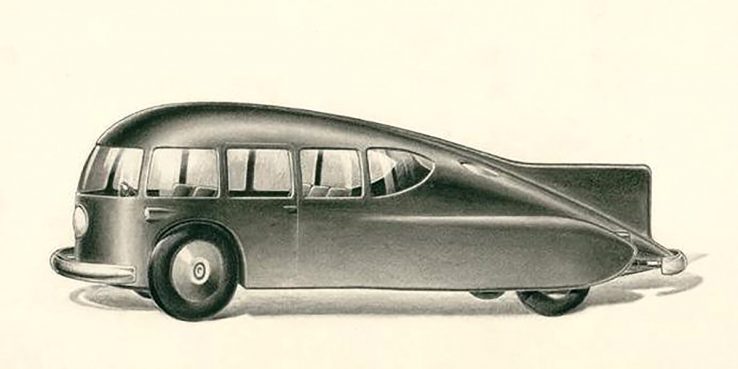

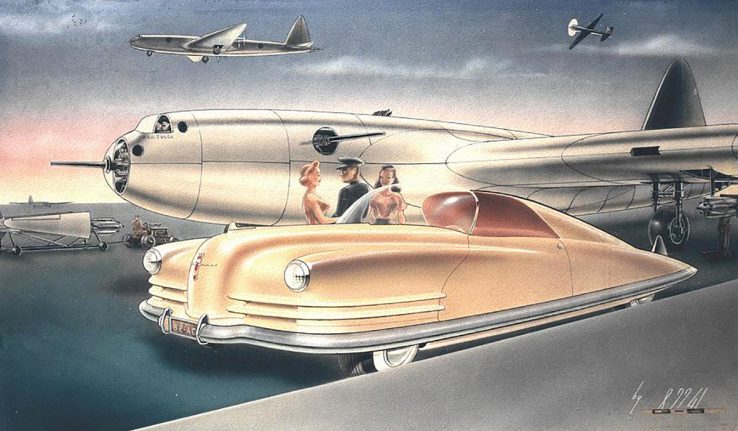

For example, in the art of Adrian “Gil” Spear, who worked with Geddes on Futurama and who presented the above two styling concepts to Chrysler in 1941 that were clearly inspired by his former employer’s designs.

5 Comments

Add YoursOne of several great twentieth-century designers, like Hugh Ferris, whose designs made a big impression mostly without being realised in full-scale. He was the father of actress Barbara Bel-Geddes (Miss Ellie in “DALLAS”).

Once again a great article on Dieselpunk architecture and design.

Thanks, Mark!

Just discovered this talented man (Mr. Bel Geddes) while I was searching for outakes from movies involving filming f/x with miniature passenger ships in water tanks and incorporating both CGI with miniatures. Mr. Geddes psychic vision with his designs particularly his vision and model of a sleek and energy efficient non-drag passenger ship became a reality in the second millennium ship building industry. Ship design progressions into more sleek shapes like Mr. Bel Geddes had envisioned came true. Amazing to think that this man’s drawings and models done back in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s for Passenger ships and for a passenger Airliner’s like Airliner no 4 look similar to NASA’s design for a passenger wing Jet with engines mounted on top. I swear his Futurama Exhibit Design in early 1930’s looks exactly like downtown Los Angeles 2021!

Thank you for this wonderful article! The post office had a great stamp and poster with a Bel Geddes’s radio design on it.