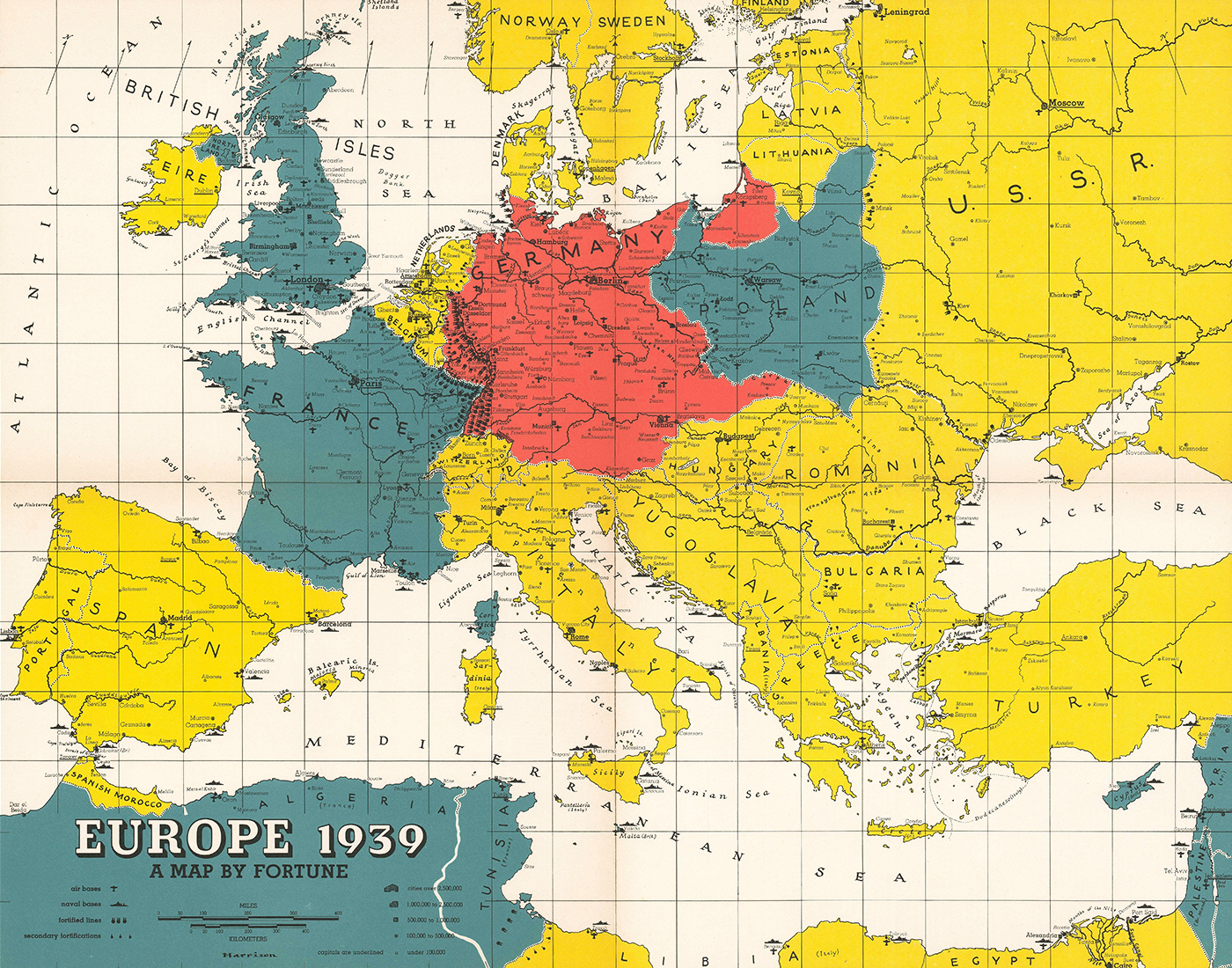

World War II started in 1939, when Germany invaded Poland and Britain and France declared war. But the Nazi conquest of Europe started years earlier.

In 1935, the coal-rich Saarland rejoined the Reich. The following year, Hitler remilitarized the Rhineland in violation of the Versailles Treaty. Austria and what is now the Czech Republic were annexed in 1938.

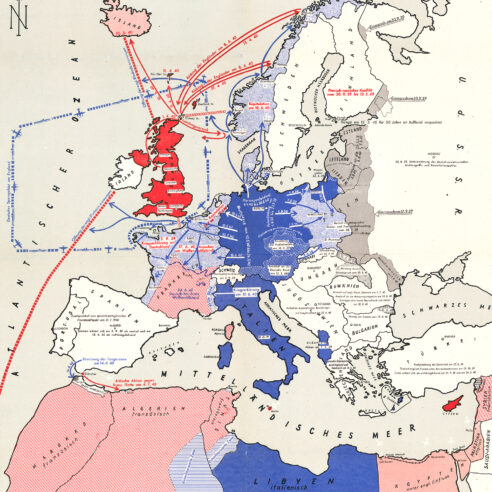

At the height of his power, Hitler ruled an empire stretching from the Franco-Spanish border in the southwest to Svalbard (Spitsbergen) in the north to the Caucasus in the east. Here is a short history of how it happened — with maps!

Aims

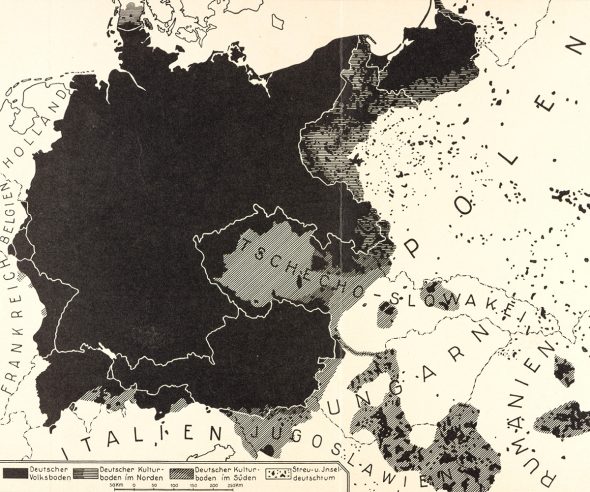

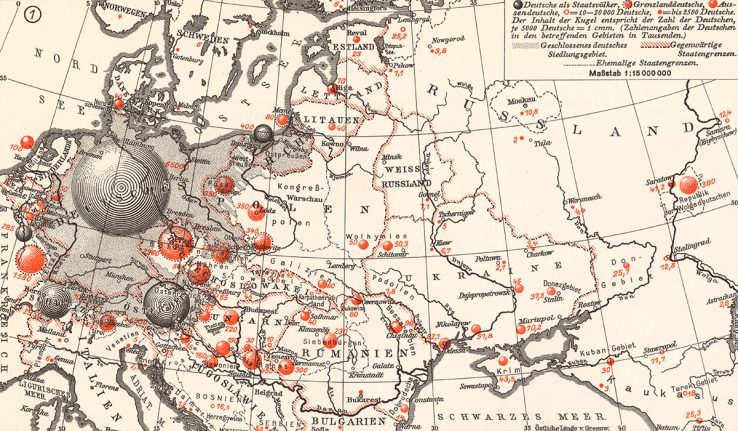

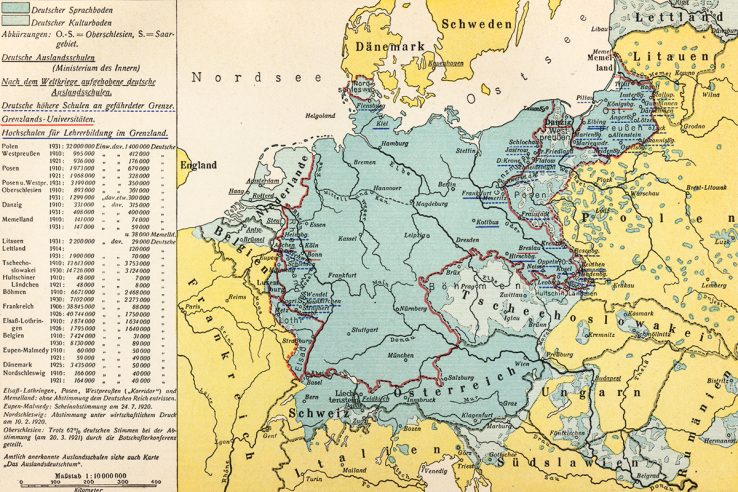

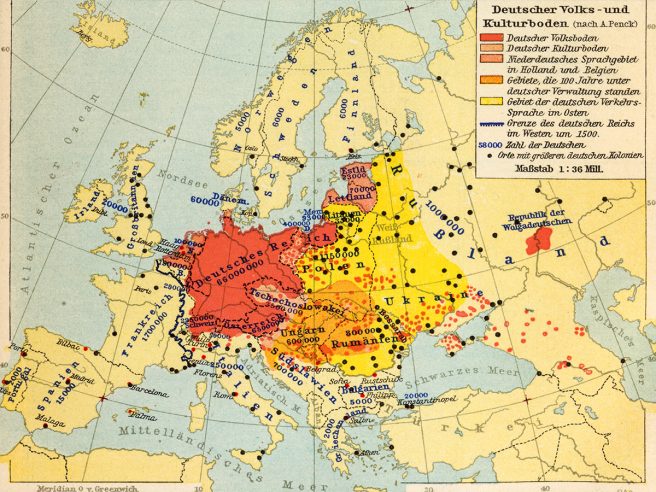

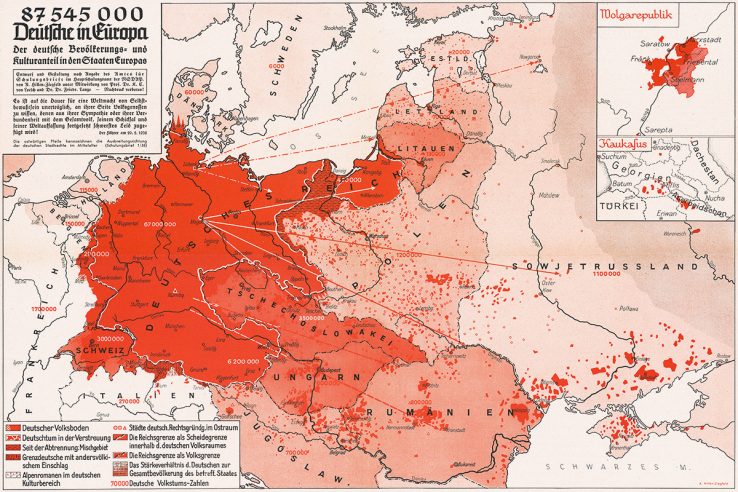

Interwar Germany wasn’t shy about its territorial ambitions. In books, maps and speeches, German nationalists made clear their determination to win (back) lands populated by ethnic Germans.

They often exaggerated the extent of Germany’s “natural” frontiers. Swathes of Central and Eastern Europe were assigned to Germany’s “cultural space”, despite German speakers being in the minority there.

The right-wing Austrian-German People’s League demanded that Austria, the German-speaking parts of Italy and Switzerland as well as the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia and the areas of Posen and West Prussia that had been ceded to Poland after the First World War be reincorporated into Germany to make it “whole” again.

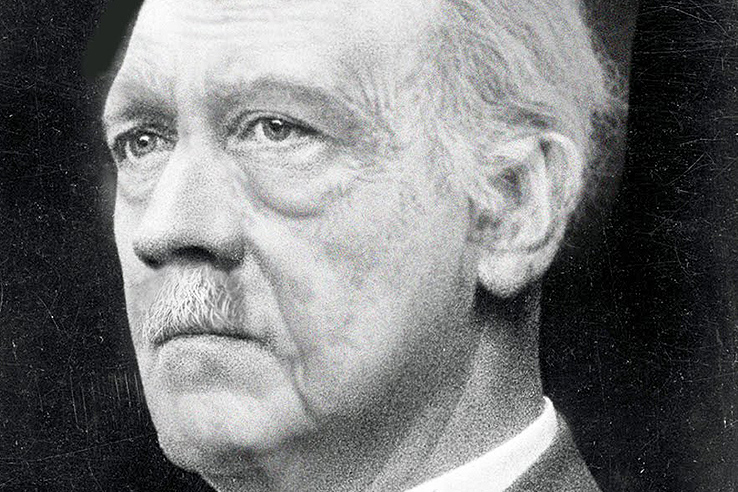

Albrecht Penck, a geographer, argued that, in addition to areas of German settlement (Volksboden), there were German “cultural” lands (Kulterboden), where German industriousness and intelligence had made their mark. This made it possible to claim for Germany parts of Europe it had never ruled, but where it had cultural or economic influence.

The Nazis ultimately rejected Penck’s argument, which was racially too inclusive and territorially too restrictive for them. Their idea of the German “nation” encompassed everyone of German ancestry, which, according to a 1938 map by Arnold Hillen Ziegfeld, added up to 87,545,000 people.

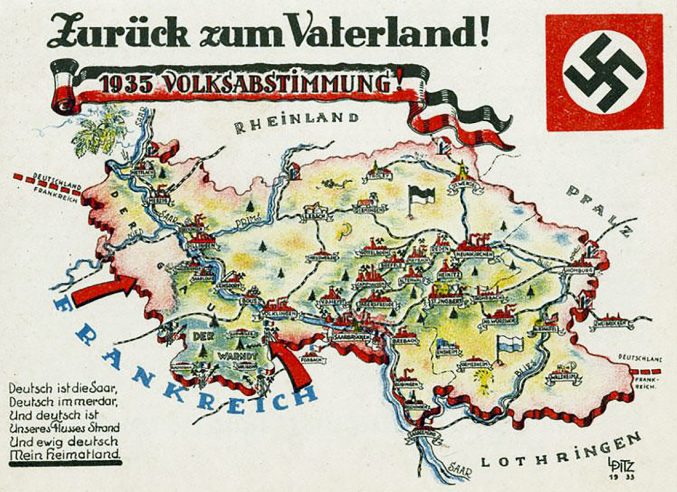

Saar

The Nazi regime’s first step in making Germany great again was the reintegration of the Saarland.

The coal-rich region had been separated from Germany after the First World War and placed under an Anglo-French League of Nations mandate. When the mandate expired in 1935, and the population voted to rejoin Germany, the Nazis could claim they had begun to overturn the “diktats” of Versailles.

Rhineland

The first real violation of the Versailles Treaty was Germany’s occupation of the Rhineland.

After France signed a defense treaty with the Soviet Union in March 1936, Hitler marched 3,000 German troops across the Rhine into the demilitarized economic heartland of Germany. Britain and France, unwilling to go to war over land that was German anyway, did not protest.

Austria

Hitler’s next move was the annexation of his native Austria. Like the return of the Saar and the remilitarization of the Rhineland, the March 1938 Anschluss of Austria was accomplished without firing a shot.

The Austrian population seemed to welcome the annexation but, just to be safe, the Nazis rigged a referendum to produce 99.7 percent support for the joining of the two German-speaking nations. Austria became an integral part of the German Reich called the Ostmark.

Sudetenland

The western border region of Czechoslovakia, itself a creation of Versailles, was home to an ethnic German minority as well as the country’s border defenses. The Germans called this the Sudetenland. Emboldened by the Western Allies’ tepid response to the Anschluss, Hitler demanded that the Sudeten Germans be brought into the Reich.

The Czechs offered the Sudetenland autonomy, which its local fascist party accepted. But this was not enough for Hitler. Britain and France agreed to split the region from Czechoslovakia and give it to Germany, but again Hitler — keen to use the crisis as a pretext for war — made additional demands: the immediate German military occupation of the Sudetenland, giving the Czechoslovaks no time to move their defenses.

To this Britain and France agreed as well at the infamous Munich Conference of September 1938. German troops moved in a month later.

But, breaking his promise not to invade the rest of Czechoslovakia, Hitler did just that five months later. The remaining Czech lands became the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Slovakia became an independent, Nazi-allied republic under Jozef Tiso.

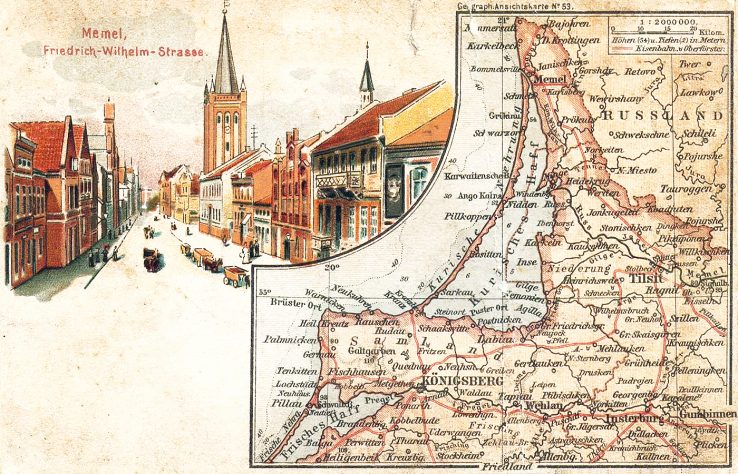

Memelland

Next on Hitler’s list was the return of the Klaipėda Region, which the Germans called Memelland, from Lithuania.

Bordering on East Prussia and centered on the Baltic port city of Memel, the territory had been detached from Germany at Versailles and then seized by Lithuania in 1923. Nationalist sentiment had been rising among its German-speaking minority for years.

Without either Western or Soviet support, the Lithuanians saw no choice but to accept Germany’s ultimatum on March 22, 1939. German soldiers had already entered Memel and the following day a German armada, carrying the Führer himself, arrived to celebrate the territory’s return to the Reich.

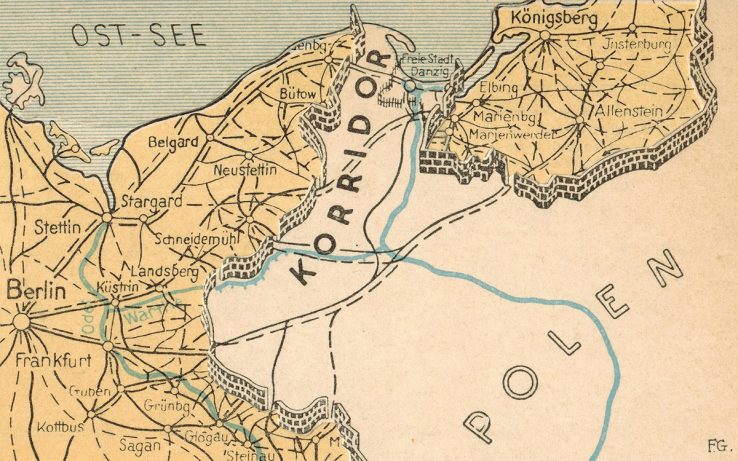

Danzig and the Polish Corridor

After Memel, the fear in Europe was that the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk) and the so-called Polish Corridor, which separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany, would be next.

The fear was justified. Hitler, convinced that the Western democracies would once again relent, ordered his generals to prepare to seize not just Danzig and the Polish Corridor but the entire western half of Poland.

In a secret protocol to the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union accepted Germany’s plan provided it would get the eastern half of Poland and the Baltic states.

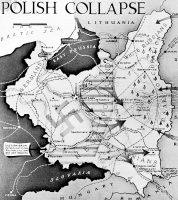

Poland

Germany invaded Poland a week after the nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union was signed. Allied Slovak units attacked from the south. The Soviet invasion from the east followed two weeks later.

Polish defense planning had concentrated on stopping the Germans at the border in order to protect the country’s economically most valuable regions in the west. The Polish government also feared that if it gave up those areas, which had once been German, Britain and France might not come to its aid and accept German gains, like they had in the case of Czechoslovakia.

The strategy was ill-advised, and indeed Polish generals knew the better plan was to establish a defensive perimeter behind such natural barriers as the Vistula and San rivers.

When the Germans did invade, Poland’s defenses were quickly overrun. Britain and France declared war on Germany but were unable to send help. Polish forces withdrew to the southeast, toward the so-called Romanian Bridgehead, where they planned to hunker down, wait for Western aid and eventually mount a counteroffensive.

But Western aid never materialized and meanwhile Soviet soldiers had started marching in from the east. At this point, a defense of the Romanian Bridgehead was no longer feasible and the Polish government ordered the evacuation of all remaining troops to neutral Romania.

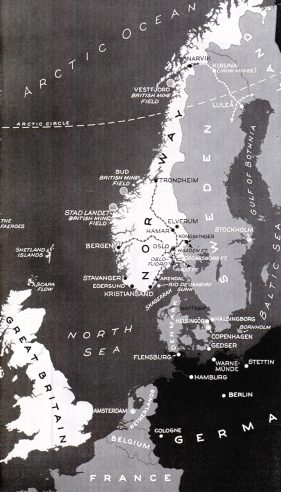

Denmark and Norway

In the early morning of April 9, German troops invaded Denmark. Within hours, they had arrived in Copenhagen. There was only a minor skirmish with the King’s Royal Guard outside Amalienborg Palace before the Danish government capitulated.

Denmark gave the Germans a springboard for the invasion of Norway, which was their real target. Norway could serve as a base for naval units, especially U-boats, to harass Allied shipping in the North Atlantic, and its occupation would secure shipments of iron ore from Sweden through the port of Narvik.

The Norwegians resisted. The geography of the country, and their familiarity with the terrain, allowed the Norwegians to hold out for two months before they were forced to surrender.

There was fear Germany might attack Sweden next, but there was no need. Surrounded by the Axis on all sides (Finland, having been invaded by the Soviet Union, was on the German side), the Swedes were in no position to join the Allies.

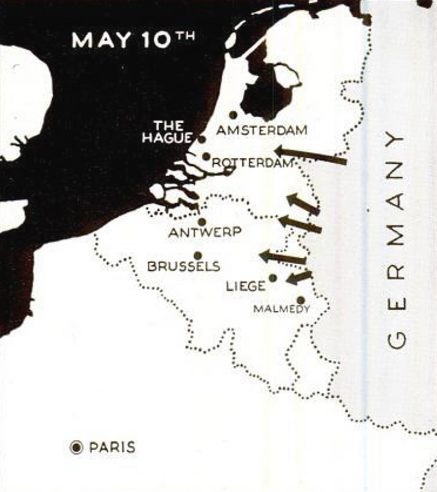

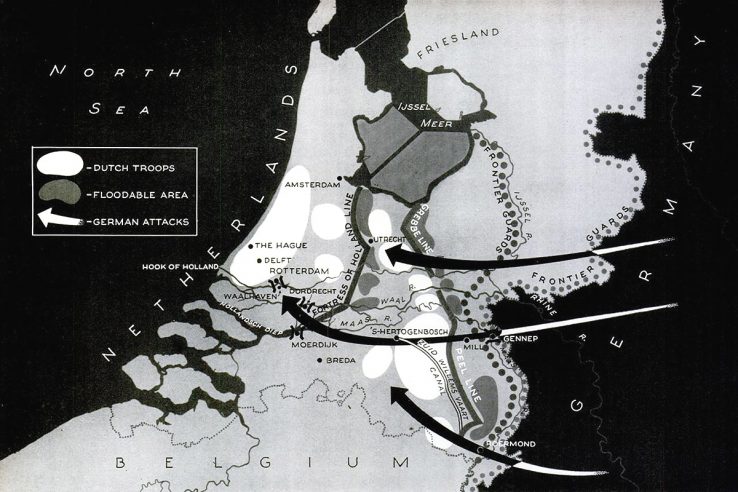

Low Countries

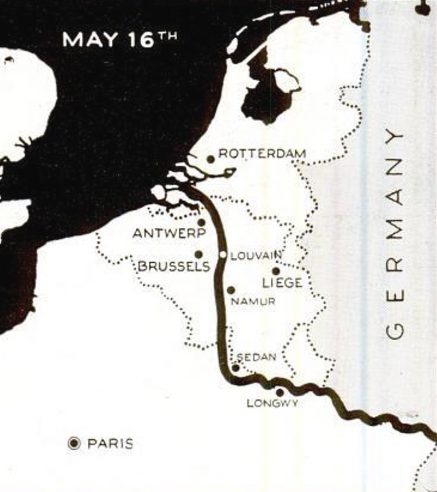

The invasion of the Low Countries was, to the Germans, only a prelude to the Battle of France. It obviously didn’t feel like a sideshow to the Dutch, who hadn’t been invaded in a hundred years. (Dutch — unlike Belgian — neutrality was respected in World War I.)

Dutch defense planning was rooted in the centuries-old method of flooding low-lying parts of the country to slow an invading force, but by 1940 the Germans could simply drop paratroopers behind Dutch lines. Airpower had defeated the Dutch Water Line.

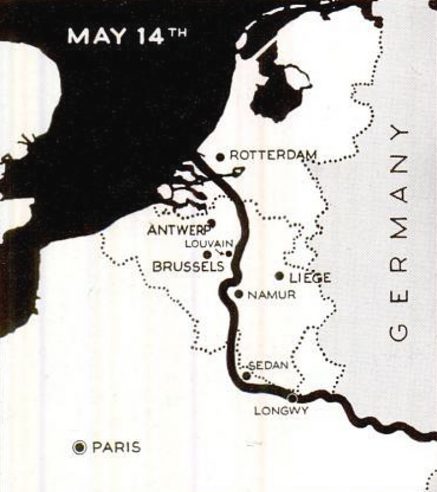

When the Germans bombed the port city of Rotterdam on May 14, and threatened to bomb other cities unless the Dutch surrendered, the Netherlands’ main fighting force capitulated.

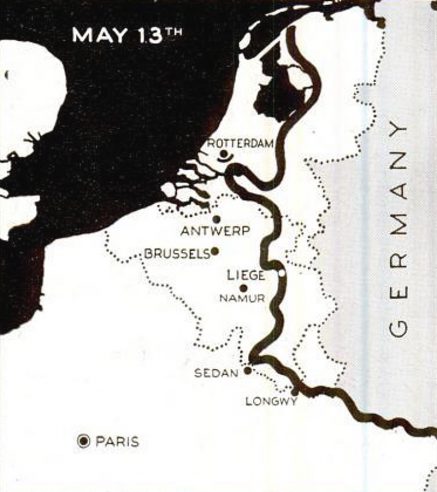

France

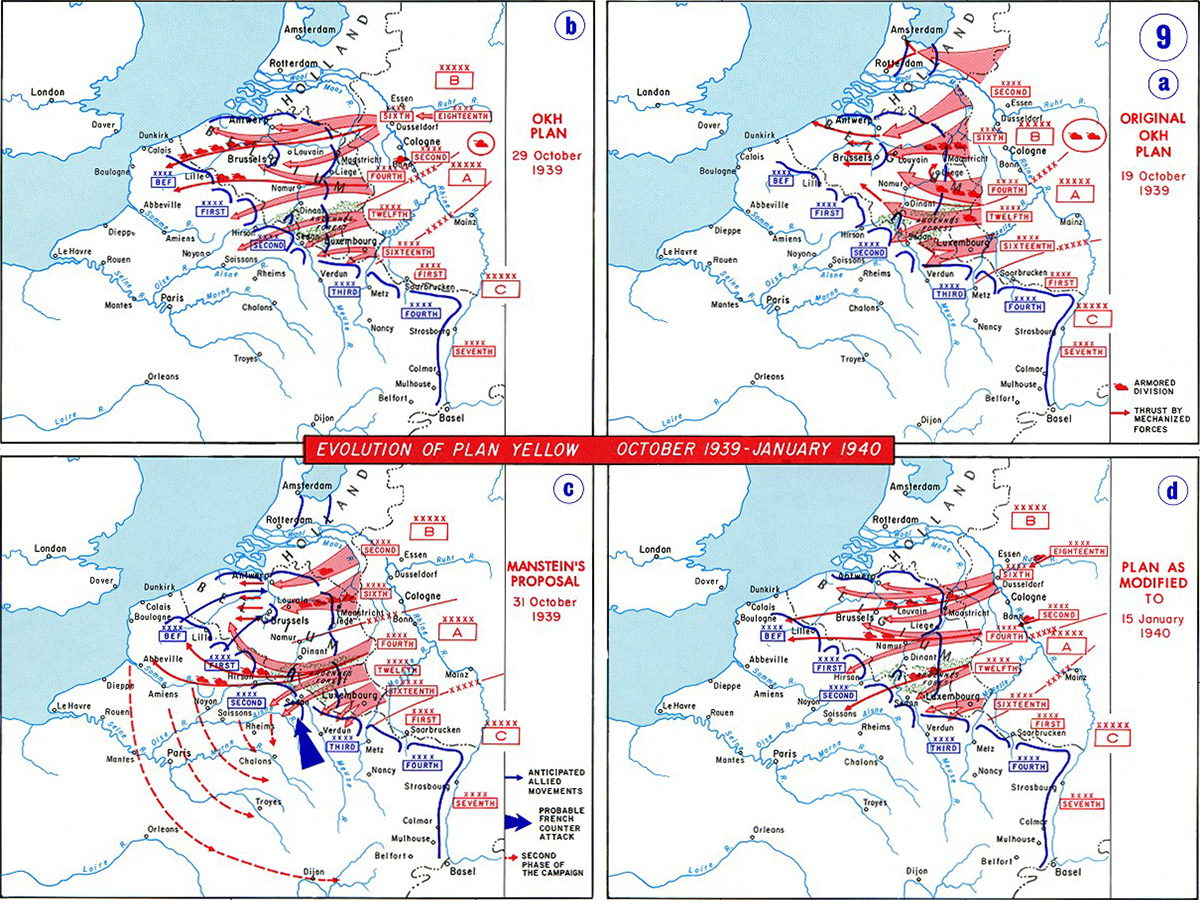

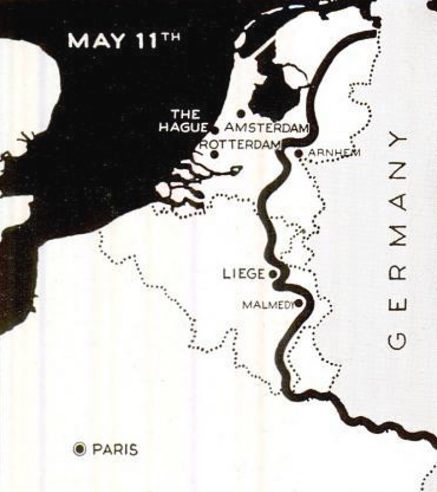

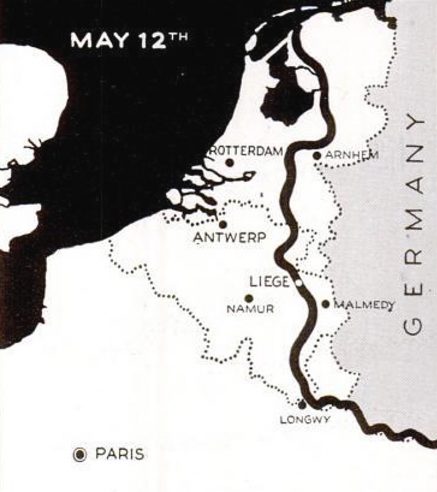

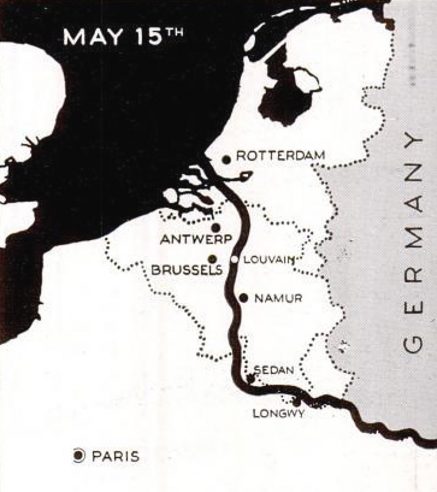

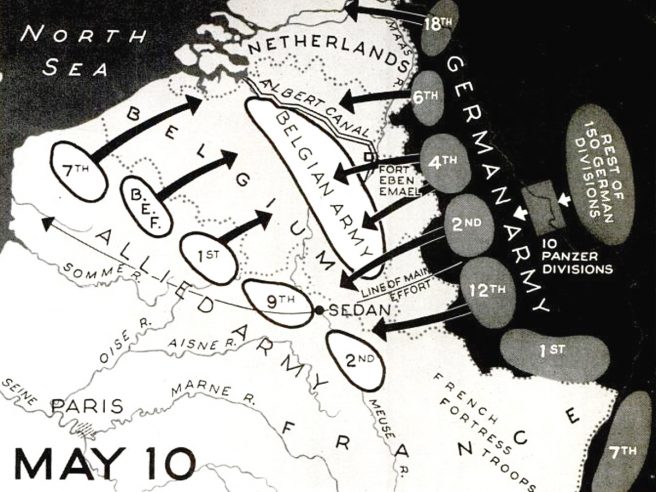

The key to Germany’s quick victory over France was the decision to invade through the Ardennes. French troops in this area were outnumbered and second-rate. France had sent its best troops across the Belgian plain to establish a defensive perimeter east of Brussels under the assumption that the Germans would take the same invasion route as they had in 1914.

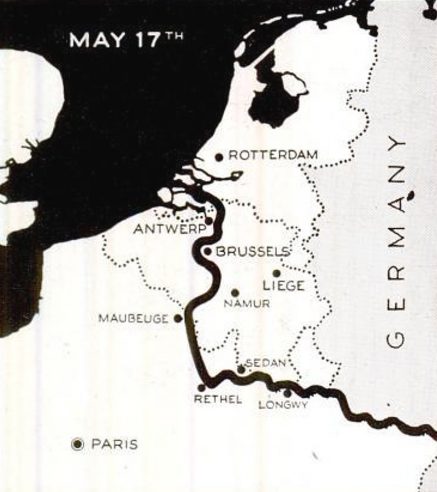

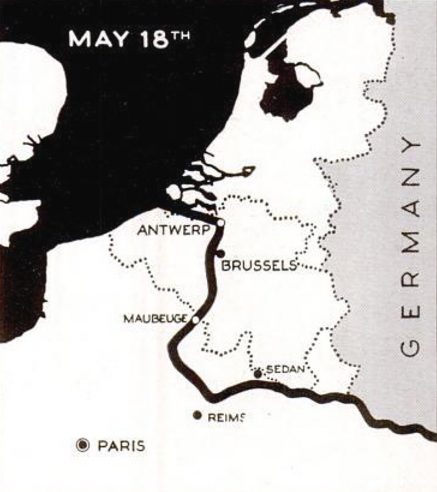

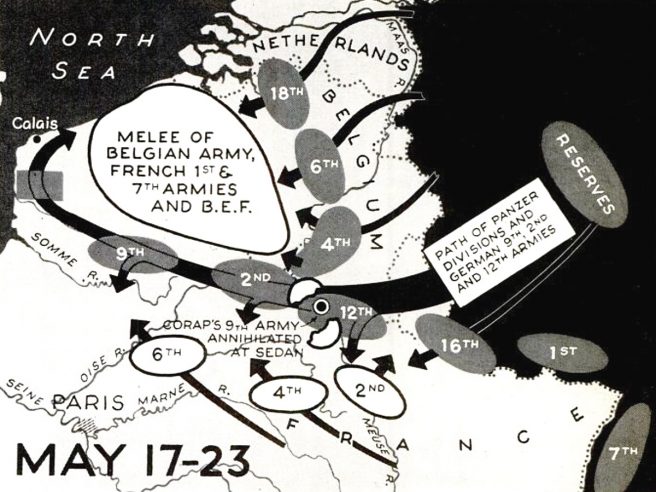

Indeed, some German troops did, but the bulk of the invading force was making its way through the forest. It took the Allies four days to recognize their mistake, by which time it was too late. German armored columns had reached the English Channel, cutting off the British and French at Dunkirk.

What looks like a masterstroke in hindsight was closer to an accident of history. Germany’s top military planner, General Franz Halder, had originally proposed an invasion through the Low Countries, called the Manstein Plan or Case Yellow, that was close to what the Allies expected. But those plans fell into enemy hands when Mayor Helmuth Reinberger of the Luftwaffe was captured with the Case Yellow plans in Mechelen on January 10. Mechanical problems had forced his plane to land and the pilot mistook the Meuse River for the Rhine, stranding them both in Belgium. Germany was subsequently forced to alter its plan of attack.

French prime minister Paul Reynaud realized the battle was lost when the Germans broke through at Sedan on May 15. When his British counterpart, Winston Churchill, visited Paris the next day to lift Reynaud’s spirits, he was told by Maurice Gamelin, the top French military commander, that there were no reserves to protect Paris. The fall of France was imminent. They best French forces could hope to accomplish now was to fight on for several more days to give the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) a chance to escape.

On May 20, Reynaud sacked Gamelin and put Maxime Weygand in command. Weygand managed to mount some counterattacks, but, again, the main benefit was to slow the German advance to the coast and give the British time to get out.

When May turned to June, and the BEF was surrounded at Dunkirk, Weygand faced a front stretching from the English Channel to Sedan with an army less than half the size of the Germans to defend it. Nevertheless, the French put up a strong resistance. At least their supply lines were shorter and German blitzkrieg tactics were no longer a surprise. The Germans, by contrast, were overstretched and increasingly relied on superior numbers and airpower, rather than superior tactics, to break through the French defenses.

Weygand’s defense in depth inflicted maximum attrition on the Germans, but he could only slow them down, not stop them. The French government declared Paris an open city on June 10. When German troops marched in four days later, they respected the declaration and the city was taken without violence.

It was only at this point that the Germans attacked the formidable Maginot Line, which was now seriously undermanned. Some fortresses held out until the very end, but the war was clearly lost. Reynaud resigned on June 16. He was succeeded by World War I veteran and Marshal of France Philippe Pétain, who, in a radio address to the French people, announcing his intention to seek an armistice with Germany.

Pétain would serve as head of the collaborationist French state in Vichy until 1944. Weygand initially collaborated with the Germans as well until the Vichy government allowed the Axis use of military bases in the French colonies.

Greece

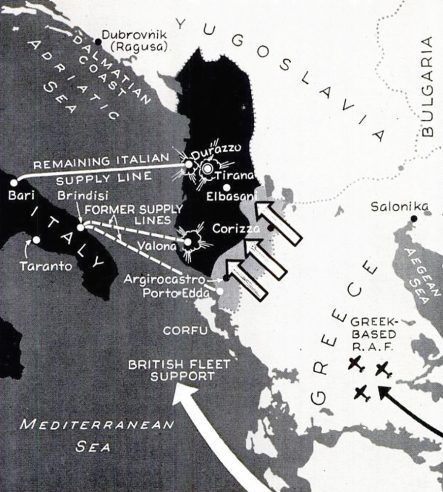

Italian forces had played only a tiny role in the fall of France, and they certainly hadn’t been instrumental. Keen to prove himself to Hitler, Benito Mussolini launched an invasion of Greece in October.

It was a disaster. Mussolini already held Albania, which meant the Greeks knew where the attack would come from. They had prepared well. Greeks defenders stopped the Italians right at the border and were even able to advance a few kilometers into Albania in January 1941. The Italians tried a second time in March, but this Spring Offensive ended no better for them than their first attempt.

The fight had also worn out the Greeks, who appealed to the British for help. Britain sent weapons, ammunition and military gear, which to Hitler raised the specter of a British threat from the south. He decided to help the Italians.

German support was made easier by Bulgaria’s accession to the Axis in March. The following month, German troops invaded from the north. The Greeks were now forced to defend a front straddling their entire border, but they resisted British suggestions for a tactical withdrawal. Axis forces were able to break through and reach Athens on April 27 and the southern coast on April 30. The conquest of Greece was completed with the capture of Crete a month later.

Hitler would later blame Mussolini for diverting German troops from the planned invasion of the Soviet Union, causing them to just fall short of seizing Moscow before the winter of 1941.

Yugoslavia

Another setback to Hitler’s plan to invade Russia was the March putsch in Yugoslavia. Pro-Western Serb nationalists overthrew the Axis-friendly regency of Prince Paul and installed the seventeen-year-old Peter II as king. Hitler immediately ordered an invasion, which began on April 6.

Following a devastating bombardment of Belgrade, which made it difficult for the Yugoslavs to coordinate their defenses, Axis forces attacked from Austria, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. It took them only two weeks to reach Belgrade.

Middle East

With the entire Balkans now under Axis control, and the newly-formed German Afrika Korps advancing on Egypt, an invasion of the Middle East seemed possible. If Germany were to simultaneously move on Gibraltar and the Suez Canal, it could trap Britain’s fleet in the Mediterranean, cut off the empire’s supply lines to India and protect Europe from a blockade by sea with the oil reserves of the Middle East and the granaries of North Africa in its possession.

The main obstacle was Turkey’s neutrality. The Nazis offered Turkey parts of Greece in exchange for joining the war on the Axis side, as well as buffer states in the Caucasus, but President İsmet İnönü turned them down. His sympathies were with the Allies and the Germans recognized that an invasion would have needlessly made an enemy out of Turkey.

Click here to learn more about Hitler’s feared invasion of the Middle East.

Russia

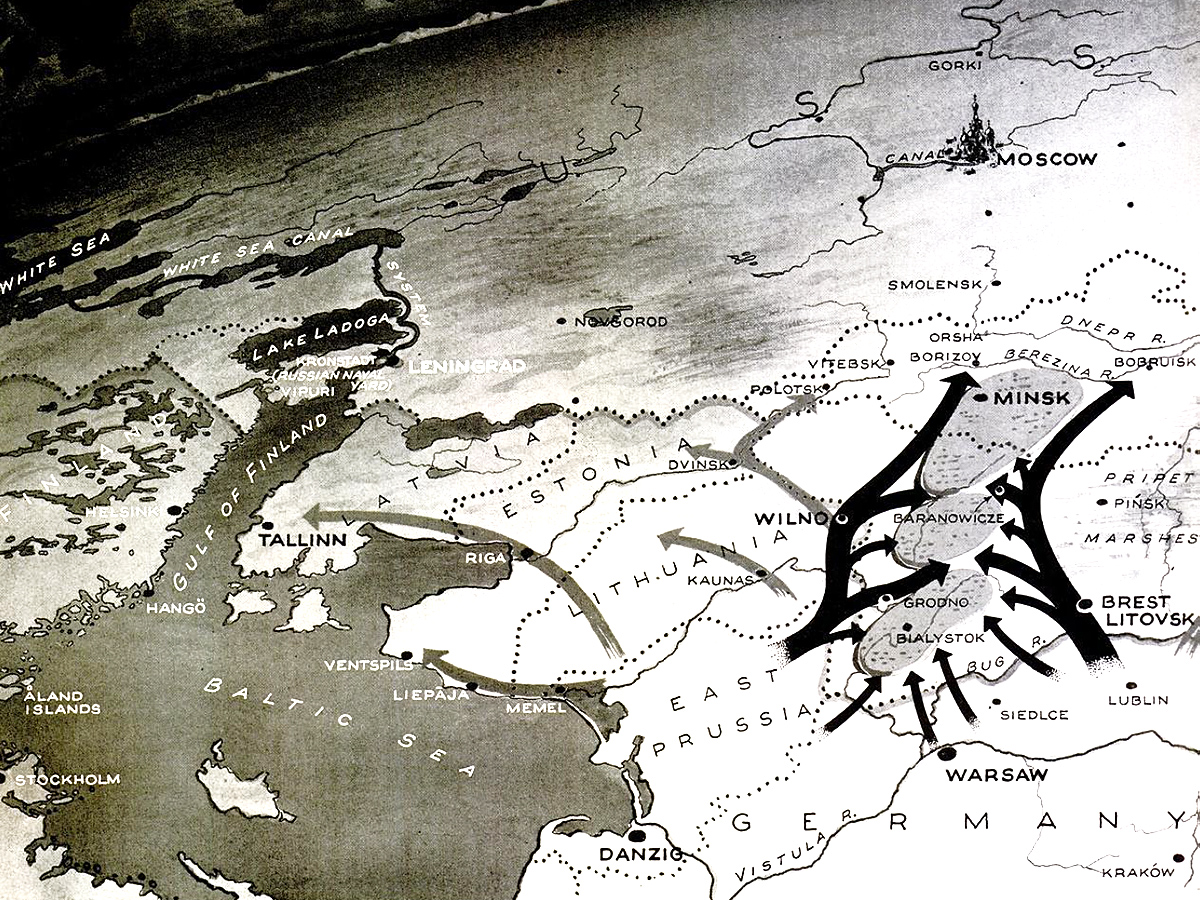

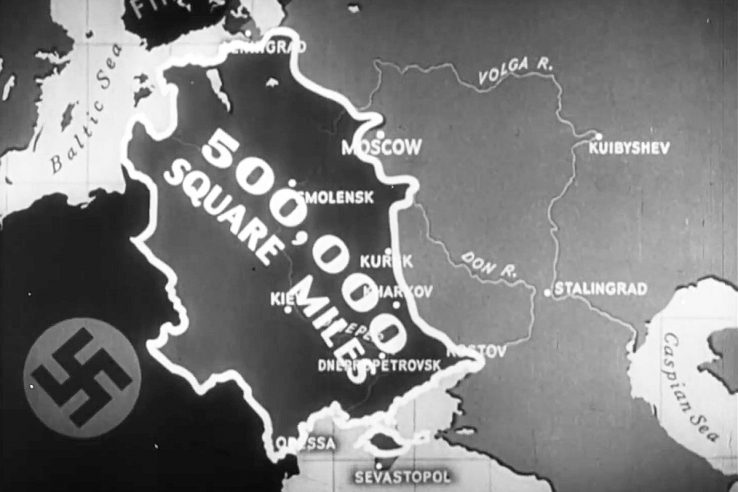

Instead of the Middle East, Hitler attacked his nominal ally, Russia. Launched in June 1941, the goal of Operation Barbarossa was to establish German control from Arkhangelsk in the north to Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea. Leningrad, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod (known as Gorky in Soviet times) and Stalingrad (now Volgograd) would all be conquered. The Soviet Union would be deprived of the bulk of its population and industrial strength.

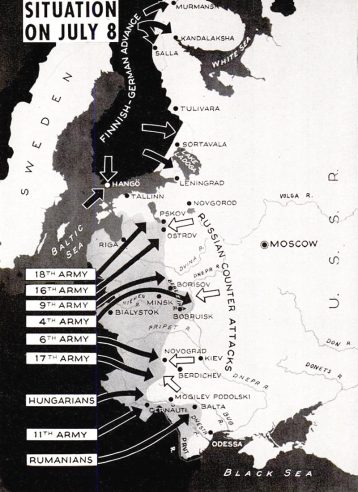

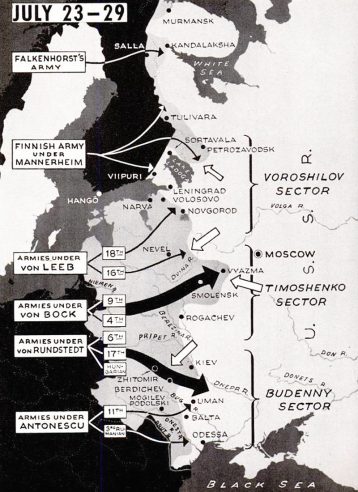

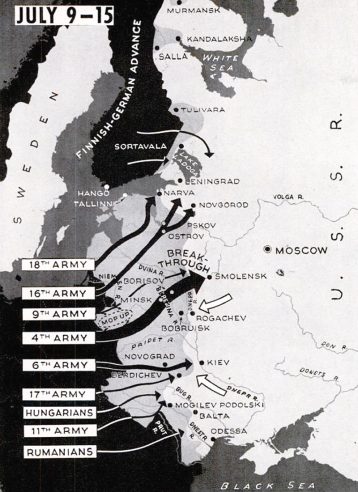

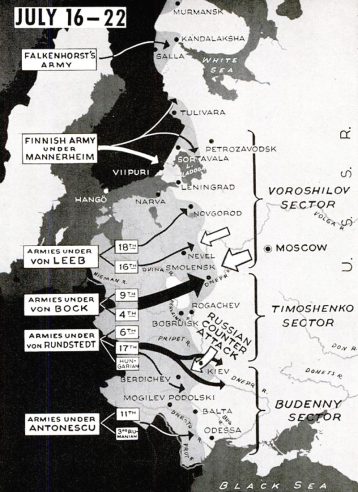

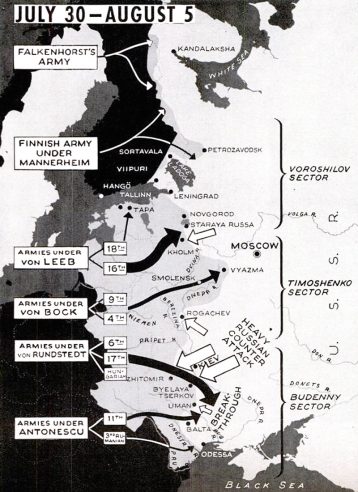

The attack was carried out in three major thrusts.

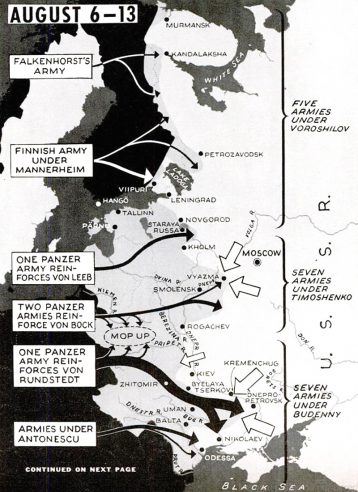

- Army Group North, under the command of General Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb and consisting of the 16th and 18th Armies of the German Wehrmacht, invaded the Baltic republics with the goal of reaching Leningrad.

- Army Group Center, under General Field Marshal Fedor von Bock and consisting of the 4th and 9th Armies and the strongest armored and air units, attacked Belarus with the goal of reaching Smolensk and eventually Moscow.

- Army Group South, under General Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt and consisting of the 6th, 11th and 17th Armies, with additional forces from Hungary, Italy, Romania and Slovakia, attacked Ukraine with the goal of reaching Kiev before continuing eastward over the steppes toward the oil-rich Caucasus.

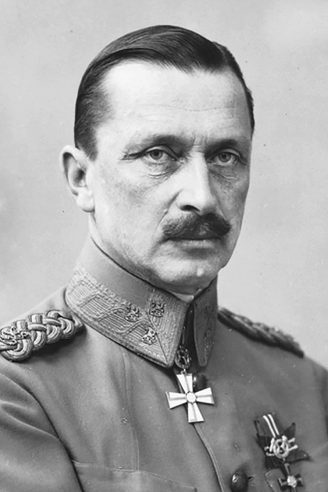

Finnish forces simultaneously launched an attempt to retake Karelia under Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim.

On the Soviet side, Marshals Kliment Voroshilov, Semyon Timoshenko and Semyon Budyonny commanded the defensive sectors. All three suffered under micromanagement from Joseph Stalin. Much like Hitler when the roles were reversed a year later, the Soviet dictator would initially allow no retreats, hampering a defense-in-depth strategy that had served Russia well during Napoleon’s invasion and which Marshal Georgy Zhukov implemented the following year.

The German occupied more than half a million square miles of Soviet territory and came within striking distance of Moscow before they were ground to a halt in the mud and snow of the Russian winter. Once he was confident the Japanese would not attack in the Far East, Stalin ordered his Siberian army to assist in the defense of the capital. The Germans lost the Battle of Moscow in January 1942. Operation Barbarossa had failed.

An angered Hitler relieved Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch as supreme commander of the German Army and took command himself. With his Panzers running out of fuel, he decided not to try for Moscow again in the spring of 1942 but rather divert his forces to the south to seize the oil fields of the Caucasus and the city that bore his enemy’s name: Stalingrad.

Stalingrad

The objective of the 1942 German summer offensive, codenamed Case Blue, was to thrust across southern Russia, cut off remaining Soviet forces in the Caucasus, take the oil and then encircle Moscow.

The Caucasus part of the operation, called Edelweiss, initially went well, until stiffer Soviet resistance and lengthening supply lines slowed the Germans down. They never reached the Caspian Sea.

They did cross the River Don and reach Stalingrad, but five months of vicious fighting over the city precipitated the reversal of all of Germany’s 1942 gains on the Eastern Front. It was the beginning of the end of Hitler’s empire.

4 Comments

Add YoursThanks for another excellent piece, Nick! I urge readers to click and enlarge all the maps. They’re great!

I often wonder why Britain and France declared war only on Germany, just one of the three countries that invaded Poland in September 1939. Russia and Slovakia got a free pass. Fear of Russia’s military might was an understandable concern, but no excuse from an ethical and political viewpoint.

Thanks, John!

Great article Nick.

The maps are excellent.

I never knew that there was a mini-fascist state (territory) in Slovakia allied with Nazi Germany when Poland was invaded.

Thanks for that.

Marc

Thank you for reading!