Alternate World War II histories typically either kill Hitler, to end the war quickly or avoid it altogether, or correct one of his many strategic mistakes (invade Russia in winter, needlessly declare war on the United States), to enable an Axis victory.

There were many more inflection points, however, any one of which could have steered history in another direction. If you want to change World War II, here are 22 ways to do it.

Roosevelt is killed

Franklin Delano Roosevelt survived an assassination attempt by Giuseppe Zangara in February 1933. Had he died, it’s not hard to imagine another president keeping the United States out of the war in Europe.

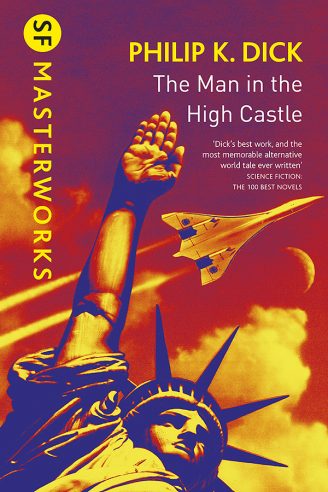

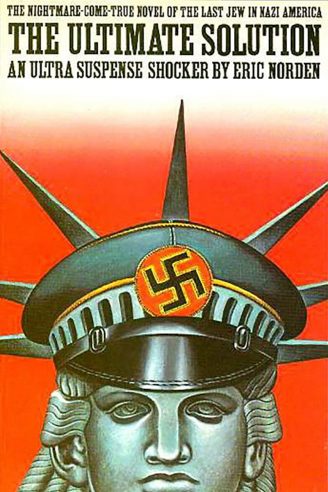

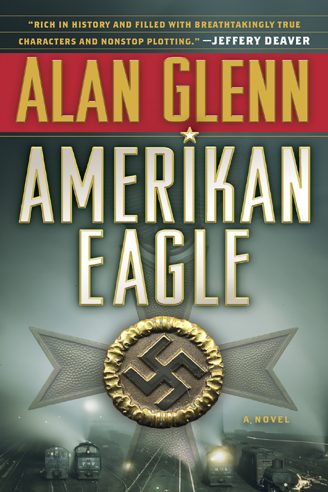

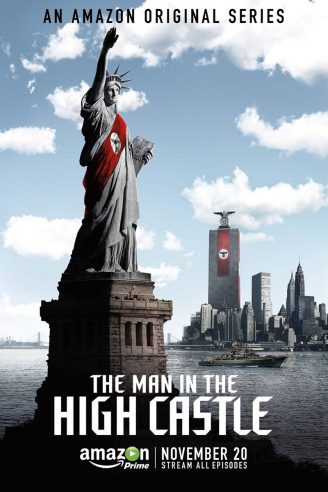

Several alternate histories take this route, including Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962), Eric Norden’s The Ultimate Solution (1973) and Brendan DuBois’ (writing as Alan Glenn) Amerikan Eagle (2015).

In Noel Hynd’s Flowers From Berlin (1985), Roosevelt is also killed, but by a Nazi assassin in 1939. Wendell Wilkie is elected president the following year.

Roosevelt loses reelection

Others let Roosevelt live but remove him from office before the war.

Wilkie is the usual replacement. Although the Republican came out in favor of FDR’s war policy after the attack on Pearl Harbor, various stories imagine how his 1940 election victory could have allowed the Axis to prevail. Examples include Robert Silverberg’s “Trips,” published in Final Stage: The Ultimate Science Fiction Anthology (1974), and Alan Rodgers’ “Ruby,” published in Full Spectrum 5 (1995).

In Barry M. Malzberg’s “Kingfish” (1992) and S. Andrew Swann’s “The Long View” (1995), the left-wing populist Huey Long survives an assassination attempt in 1935 and is elected president the following year. Swann’s story is unusual in that it has Long start World War II.

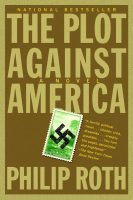

In The Plot Against America (2004), Philip Roth has Charles Lindbergh, the hero aviator and America Firster, elected president in 1940. FDR returns the following year, though, when Lindbergh disappears — just in time to put history back on the right track. (Our review of the 2020 television adaptation here.)

Britain stays out or makes peace

A popular way to keep the United Kingdom out of the war is to have Edward VIII, who was sympathetic to Hitler, remain king. In D.J. Taylor’s The Windsor Faction (2013), Wallis Simpson dies in surgery, preempting the 1936 abdication crisis. (The British government was opposed to the king marrying a divorcée.) In Jo Walton’s Farthing (2006), a similar cabal of Nazi-sympathizing aristocrats accepts Rudolf Hess’ peace offer in 1941.

In Guy Walters’ The Leader (2003), Simpson lives but Edward refuses to give up the throne, precipitating a constitutional crisis that ends with fascist party leader Oswald Mosley becoming prime minister and doing a deal with Hitler.

Another popular scenario is to keep Winston Churchill out of 10 Downing Street.

Edward Wood, the Earl of Halifax, who did argue for peace talks when Allied troops were trapped at Dunkirk, usually takes the fall. Examples include Stephen Badsey’s “Disaster at Dunkirk,” published in Peter G. Tsouras’ Third Reich Victorious: Alternate Decisions of World War II (2002, our review here) and C.J. Sansom’s Dominion (2012, review here).

John Charmley is kinder to Halifax in “What If Halifax Had Become Prime Minister in 1940?”, published in Prime Minister Portillo and Other Things that Never Happened (2003). He imagines Hitler would invade Russia and lose the war anyway. Britain emerges from the conflict still a world power instead of subservient to the United States.

In the video game Turning Point: Fall of Liberty (2008), Churchill died in a car accident in 1931 and Neville Chamberlain is still prime minister when Germany invades the UK. After defeating Britain and Russia, and conquering the Middle East and East Asia, the Axis powers launch an invasion of the United States in 1953.

War over Czechoslovakia

Had Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier, the French premier, held firm at Munich and refused to allow Hitler to annex the German-speaking parts of Czechoslovakia, World War II could have started a year early, when neither the Western Allies nor Germany were completely ready.

This was, in fact, the fear of both Italian dictator Benito Mussolini and German military leaders, some of whom were plotting a coup in case Hitler persisted. Robert Harris tells this story in his lightly fictionalized Munich (2017).

There are surprisingly few alternate histories that start the war in 1938. Harry Turtledove’s The War That Came Early series (2009-14) is the exception. In it, the Spanish Civil War ends in stalemate, Germany allies with Poland against the Soviet Union and Japan invades Siberia.

France doesn’t fall

We think of the 1940 fall of France as almost inevitable. Many reflections have been written on French “decadence” and superior German Blitzkrieg tactics. But it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to change the outcome.

Military historian Mark Grimsley has pointed out that the Western Allies had more and heavier tanks and more fighting men than the Germans. Neither the French public nor French military commanders were defeatist. If anything, it were Hitler’s generals who feared the worst.

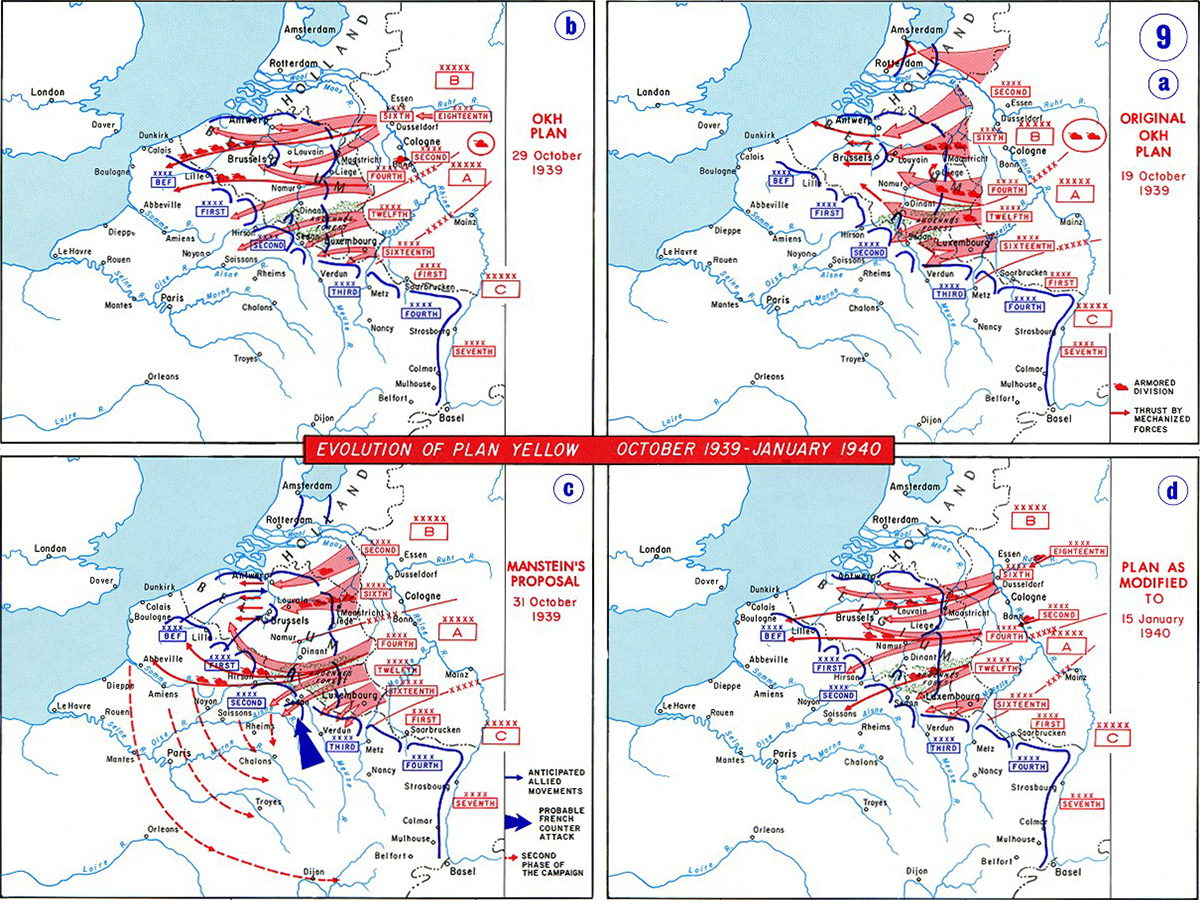

The key to the German victory was the decision to thrust into France in an armored offensive through the Ardennes, followed by an audacious crossing of the Meuse River near Sedan. The French troops in this area were outnumbered and second-rate. France had sent its best troops across the Belgian plain to establish a defensive perimeter east of Brussels under the assumption that the Germans would take the same invasion route as they had in 1914. It took the Allies four days to recognize their mistake, by which time it was too late. German armored columns had reached the English Channel, cutting off British and French troops at Dunkirk.

What looks like a masterstroke in hindsight was really an accident of history. Germany’s top military planner, General Franz Halder, had originally proposed an invasion through the Low Countries, called the Manstein Plan or Case Yellow, that was pretty close to what the Allies expected. But those plans fell into enemy hands when Mayor Helmuth Reinberger of the Luftwaffe was captured with the Case Yellow plans in Mechelen on January 10, 1940. Mechanical problems had forced his plane to land and the pilot mistook the Meuse River for the Rhine, stranding them both in Belgium.

Allow Reinberger to safely land in Cologne, where he was due to deliver the Case Yellow plans to the 1st Air Corps commander, and the war could have gone very differently. Allied troops could have tied down the Germans in Belgium. The French Third Republic would most likely have survived. Without access to French ports, Germany’s ability to wage submarine warfare would have been limited. Britain might not have suffered the Blitz. Germany would have been in no position to launch invasions of North Africa and the Soviet Union. A protracted Western campaign may even have persuaded German generals, who until the fall of France were deeply skeptical of Hitler’s self-described strategic genius, to remove the Nazi leader and sue for peace.

The only alternate-history novel I could find that follows this scenario is Alastair Reynolds’ Century Rain (2004). It takes place in an alternate 1950s where the early end of World War II has slowed technological progress and fascists now rule France.

Disaster at Dunkirk

The almost miraculous evacuation of Allied forces from Dunkirk begs an alternate history.

In fact, there are many in which the British Expeditionary Force and the remnants of the French army are destroyed and Britain is forced to capitulate. Examples include Inder Dan Ratnu’s Alternative to Churchill: The Eternal Bondage (1974), Andrew Roberts’ and Niall Ferguson’s “What if Germany had invaded Britain in May 1940?”, published in Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals (1997), and Guy Saville’s The Afrika Reich (2011) and its sequel, The Madagaskar Plan (2015).

In Saville’s novels, Germany takes over the French colonies in Africa. It deports the entire black population to Deutsch Westafrika, also known as “Muspel”, and Europe’s Jews to Madagascar, which is administered by the SS. Britain keeps Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Rhodesia and the Sudan. Italy, Portugal and Spain also retain their colonies. An African war now looms between Britain, Germany and Portugal.

Michael Peck, by contrast, has argued in The National Interest that the loss of some 200,000 British troops at Dunkirk should not have been fatal. It was the Royal Navy that prevented a German invasion of the United Kingdom and the Royal Air Force that won the battle in the air. But the destruction of the British Expeditionary Force would have been devastating to morale. British commanders might subsequently have hesitated to take the fight to the Axis in North Africa and Churchill might not have been able to send troops to Greece in March 1941 in a futile, but politically significant, show of support.

No Italian invasion of Greece

Hitler spent his dying days in the bunker under the Reich Chancellery in Berlin blaming his Italian ally, Mussolini, for Germany’s defeat. If only the Duce hadn’t disastrously invaded Greece in October 1940, requiring Hitler to delay his invasion of the Soviet Union to help, the war, he believed, could have been won.

William Sanders presents just such a scenario in “Duce,” first published Asimov’s Science Fiction (August 2002). In it, Nazi agents travel back in time and kill Mussolini before he can launch his Balkan misadventure.

Frederic Mullally’s Hitler Has Won (1975) similarly cancels the Balkan campaign and adds a Japanese attack on Vladivostok to allow the Axis to defeat the Soviet Union.

Invasion of the Middle East

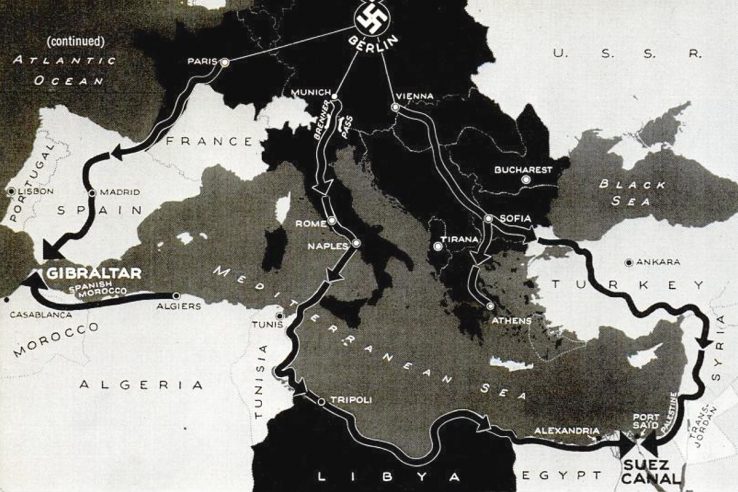

By the spring of 1941, Hitler controlled all of Western Europe and the question was where he would go next? Attempt an invasion of Britain? Or move into the Middle East and grab its oilfields? (Few anticipated at the time he would break his nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union.)

Life magazine suggested that year that Germany might move on Gibraltar as well as the Suez Canal to trap Britain’s fleet in the Mediterranean, cut off its supply lines to India and protect Europe from a blockade by sea with the oil reserves of the Middle East and the granaries of North Africa in its possession.

The prospect alarmed the Americans, who feared German troops could eventually reach Dakar on the West African coast and from there menace the Western Hemisphere.

The trouble — from Germany’s perspective — was Turkish neutrality. President İsmet İnönü had considered an alliance with the Soviet Union and the West to contain Nazi power before the war, but then the Soviets signed their nonaggression pact with Germany in 1939 and the Turks felt there was no point in allying with Britain and France alone.

To give the Germans a chance of reaching the Middle East, either Turkey needs to change its mind or Germany needs to violate its neutrality.

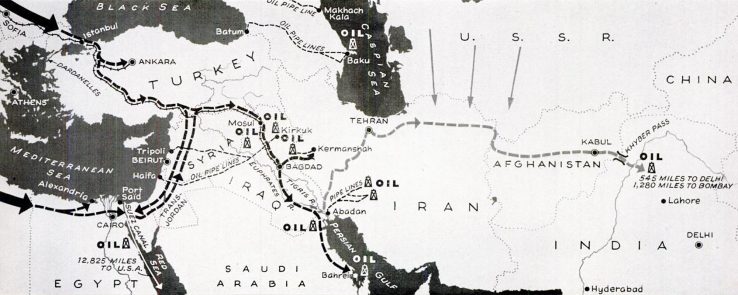

Hitler had offered İnönü parts of Greece in exchange for joining the war on the Axis side as well as buffer states in the Caucasus. John H. Gill imagines this would have been enough for the Turks in “Into the Caucus,” published in Third Reich Victorious. He even has Germany and Turkey team up to attack Russia from the south.

John Keegan argues in “How Hitler Could have Won the War: The Drive for the Middle East, 1941,” published in What If? The World’s Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been (1999), that the Turks, though “doughty fighters,” lacked the equipment to fend off a German invasion. Had Hitler decided to use Bulgaria and Greek Thrace as a springboard to invade European Turkey, capture Istanbul, cross the Bosphorus and capture Anatolia, Keegan doesn’t see what could have stopped him.

A rapid advance to the Caucasus barrier, Russia’s frontier with Turkey, would have secured the Wehrmacht‘s flank with the Soviet Union. From Anatolia, it could easily have irrupted into Iraq and Iran, thrust its tentacles southward into Arabia, and positioned its vanguards to envelop the Caspian Sea and menace Russian Central Asia.

Bryan Perret suggests in “Operation Sphinx: Raeder’s Mediterranean Strategy,” published in The Hitler Options: Alternate Decisions of World War II (1995, review here), that Germany could have captured Gibraltar and Malta if Hitler had taken Admiral Erich Raedar’s advice. Without those critical bases, Britain could have been pushed out of upper Egypt, although Perret speculates that the Allies would then have prioritized evicting the Italians from East Africa.

Ken Delve gives a similar scenario in Disaster in the Desert: An Alternate History of El Alamein and Rommel’s North Africa Campaign (2019). The Allied invasion of Tunisia fails, Erwin Rommel defeats Bernard Montgomery and seizes Egypt, leaving his Afrikakorps well-placed to sweep up through the Middle East.

Alexander Rooksmoor analyzes a similar scenario in Other Roads II: Further Alternate Outcomes of the Second World War (2014).

Sea Lion is a success

Operation Sea Lion was the codename for the planned German invasion of Great Britain. Little came of it. The plan was abandoned as early as September 1940, when the Germans realized that Britain had both air and naval superiority.

Given that the German navy had no purpose-built landing craft or experience in amphibious warfare, the original plan, which called for landings from Dorset to Kent, was scaled down to a landing of nine division with around 67,000 men. Once they had secured the coast, the plan was to push north and encircle London. The Germans expected that would compel the British to surrender.

The 1943 American propaganda film Why We Fight: The Battle of Britain presents something close to this scenario. Click here to learn more about it.

Plans for occupation included the division of the United Kingdom into six military command zones with German troops stationed primarily in the south.

Examples of Operation Sea Lion succeeding in alternate history include Norman Longmate’s If Britain Had Fallen (1972), Len Deighton’s SS-GB (1978) and the BBC mini-series that was based on it (2017, our review here), Robert Blumetti’s The Lion is Humbled: What If Germany Defeated Britain in 1940? (2003), Murray Davies’ Collaborator (2003) and Martin Marix Evans’ Invasion! Operation Sea Lion, 1940 (2004).

In Gordon Stevens’ And All the King’s Men (1990), the Germans conquer England but the British continue the fight in Scotland.

Kenneth Macksey’s Invasion: The Alternate History of the German Invasion of England, July 1940 (1990) is a fictional campaign history of a German invasion of the United Kingdom. Michael Cronin’s Against The Day trilogy (1998-2005) centers on young resistance fighters in Nazi-occupied Sussex. In John Bowen’s No Retreat (1994), Britain capitulated in 1942. In the present day, a British government-in-exile operates out of a suburb of Washington DC. The world is divided between America, Germany and Japan.

In film, a Nazi occupation of Britain was most famously portrayed in 1964’s It Happened Here. It showed the country under a collaborationist fascist regime led by Oswald Mosley.

Better Barbarossa

Hitler was famously erratic in directing the war on the Eastern Front. When Operation Barbarossa failed to conquer Moscow — and Germany was running out of oil — Hitler turned his attention to the Caucasus and launched Case Blue the following year, which eventually got bogged down in Stalingrad.

What if the Germans had succeeding in taking Moscow? James Lucas explores this possibility in “Operation Wotan: The Panzer Thrust to Capture Moscow, October-November 1941,” published in The Hitler Options. Various novels are also premised on it.

In Jimmy Guieu’s La Stase achronique (1976), after defeating Moscow, Germany knocks America out of the war with V-5 rockets. In the present day, it has a base on the Moon and landed a man on Mars.

In David Downing’s The Moscow Option: An Alternative Second World War (1979, review here), Hitler falls into a coma and the German army, free of his meddling, marches into Moscow in October 1941.

In Owen Sheers’ Resistance (2007), the fall of Moscow and victory on the Eastern Front put Germany in a strong enough position to beat back the Allied landings at Normandy and launch a counter-invasion of the United Kingdom.

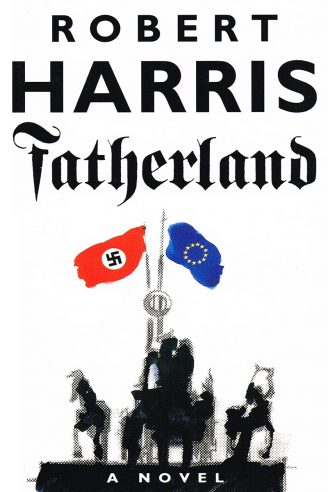

Another option is having Case Blue succeed. Robert Harris does in Fatherland (1992), although he diverges from our timeline at other points as well: Reinhard Heydrich survives an assassination attempt in 1942 and a massive U-boat campaign forces a starving Britain into submission in 1944.

No Barbarossa

Rather than a successful German invasion of Russia, how about no invasion?

This scenario is unpopular and, given that the whole point of the war for Hitler was to gain living space for the German people in the East, unlikely. However, there are a few alternate histories that explore this possibility: Hilary Bailey’s “The Fall of Frenchy Steiner,” published in New Worlds (June 1964), and Jack Wodhams’ “Try Again,” published in Amazon Stories (November 1968).

Third wave at Pearl Harbor

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was carried out in two waves. The first, consisting of 183 planes, targeted the ships. The second, consisting of 171 planes, attacked American hangars and aircraft. A third wave was contemplated to destroy fuel and torpedo storage, maintenance and dry-dock facilities, but Admiral Chūichi Nagumo decided against it, fearing that Japanese losses would outweigh the gains.

Many have argued in hindsight that Nagumo made a mistake. By sparing the onshore facilities, he made it possible for the United States to recover relatively quickly from the attack. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, later commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, believed a third attack wave could have prolonged the war by two years.

Frank Shirer imagines an even worse scenario in “Pearl Harbor: Irredeemable Defeat,” published in Peter G. Tsouras’ Rising Sun Victorious: The Alternate History of How the Japanese Won the Pacific War (2001). The aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, which in the real world was delayed by bad weather, has arrived in Pearl Harbor when the attack takes place. The battleship Nevada is sunk in the middle of the channel leading into the harbor, blocking it for months.

In Harry Turtledove’s Days of Infamy series (2004-05) and Robert Conroy’s 1942 (2009), the Japanese follow up with an invasion and occupation of Hawaii. There were Japanese military leaders who argued for this, but Nagumo thought it too risky and the army didn’t want to divert troops from China and Southeast Asia.

In Yoshio Aramaki’s novel series Konpeki no Kantai (1990-96) and the anime television series that was based on it (1993-2003), Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, is thrown back in time and given a chance to correct Nagumo’s mistakes. Japan manages to destroy not just Pearl Harbor but the entire US Pacific Fleet. America eventually surrenders, after which Germany, alarmed by Japan’s easy victories, declares war on its Axis ally.

David L. Alley tells an altogether different tale in December 7, 1941: A Different Path (1995). Rather than Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attack Vladivostok and invade Siberia. The Soviet Union is forced to fight a war on two fronts while America remains on the sidelines.

Heydrich lives

Reinhard Heydrich surviving his assassination by Czechoslovak resistance fighters is unlikely on its own to influence the outcome of the war. But many alternate histories let the ambitious SS officer live in order for him to play a major role after the war.

In Harry Mulisch’s De Toekomst van Gisteren (1972), the July 20, 1944 plot kills Hitler and Ludwig Beck takes over as president. After he signs a separate peace with the Western Allies, however, Beck is overthrown by Heydrich and Himmler. The former eventually takes over as Führer.

In Robert Harris’ Fatherland (1992, review here), Heydrich has succeeded Himmler as head of the SS and is destroying all evidence of the Final Solution to pave the way for a détente with the United States. He is mentioned as a possible future Führer.

In Amazon’s television adaptation of The Man in the High Castle (2015-19, review here), Heydrich, by the 1960s famous for overseeing the German colonization of Africa, can no longer wait and stages a coup against Hitler.

Germany gets the bomb first

In the real world, Germany neglected its atomic bomb project and the Americans got there first. What if the roles were reversed?

Robert C. Fried argues in “What If Hitler Got the Bomb? (1944),” published in What If? Explorations in Social-Science Fiction (1982), that, even if the Nazis had got the bomb first and destroyed Leningrad and London, they still would have lost the war due to superior Allied air power.

Forrest Lindsey similarly argues in “Hitler’s Bomb: Target: London and Moscow,” published in Third Reich Victorious, that the Allies would not have capitulated. He imagines Germany building two nuclear bombs and using them against London and Moscow. Winston Churchill survives the bombing of the former. General Georgy Zhukov takes over in the Soviet Union when the Communist Party leadership is wiped out. Neither is prepared to give up the fight. The war continues much as it did in the real world, except the Americans speed up the Manhattan Project and D-Day coincides with the nuclear destruction of Berlin. Rommel, still alive, negotiates the German surrender.

On the other side of the debate, there are those who allege that the Germans in fact developed a nuclear weapon first. Geoffrey Michael Brooks and Rainer Karlsch claim in Hitler’s Terror Weapons (2002) and Hitler’s Bomb (2007), respectively, that a team of scientists led by Kurt Diebner successfully detonated a nuclear device near Ohrdruf, Thuringia in March 1945. Others maintain that the Germans tested a nuclear weapon on the island of Rügen in late 1944, which was home to a small air base at the time. There is no proof either happened.

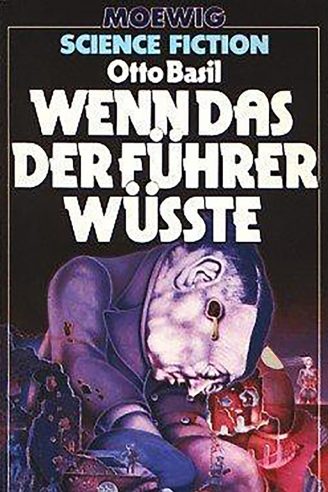

Brooks speculates that the objective of the Ardennes Offensive was to recover V-2 launch sites in the Low Countries which could target London. The idea was to equip the missiles with primitive uranium bombs and try to force the British out of the war at the last minute. Otto Basil’s Wenn das der Führer wüßte (1966) and Jean Mazarin’s L’histoire detournée (1984) follow this scenario.

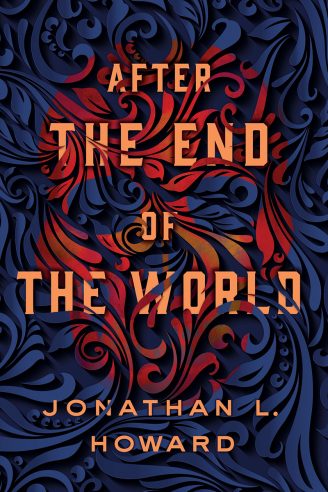

In A. Edward Cooper’s The Triumph of the Third Reich (1999), the Germans use the atomic bomb to defeat the D-Day invasion of Normandy. In Jonathan L. Howard’s After the End of the World (2017), they use the bomb against Moscow.

In Bruce Quarrie’s Hitler: The Victory That Nearly Was (1988), Germany starts its own “Manhattan Project” in 1939 and postpones the invasion of the Soviet Union to 1942. In the role-playing game Reich Star, Germany deploys nuclear weapons in 1943 and is able to conquer the whole world together with Japan. Two centuries later, the Axis powers control the Solar System and have enslaved technologically inferior alien races.

In the video game Wolfenstein: The New Order (2014), it’s New York that suffers atomic destruction at the hands of the Third Reich. In Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle, it’s Washington DC. In both cases, the nuclear attacks pave the way for an Axis invasion of the United States.

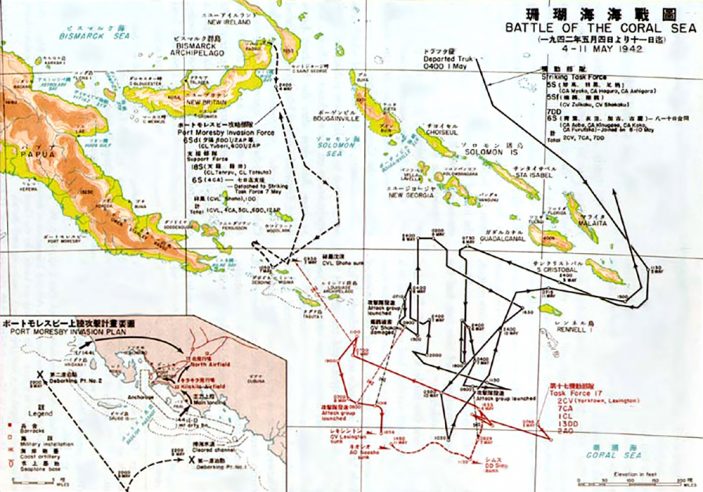

Japan wins the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea was the first setback for Japan after Pearl Harbor. Although the two sides lost roughly the same number of ships, the battle prevented Japan from invading New Guinea.

It doesn’t take much imagination to change the outcome, given how evenly matched the Allied and Japanese forces were. Sink the American Yorktown and allow the Japanese fleet carriers Shōkaku and Zuikaku to emerge from the battle unscathed and it would be possible for Japan to press ahead with landings at Port Moresby.

John H. Gill and John Hooker explore such scenarios in “Samurai Down Under: The Japanese Invasion of Australia,” published in Rising Sun Victorious, and The Bush Soldiers (1984), respectively. Both argue that a Japanese occupation of New Guinea could have served as a springboard for the invasion of Australia.

Another benefit for the Japanese of having the Shōkaku and Zuikaku remain intact is that they can then take part in the crucial Battle of Midway. In the real world, it was the Yorktown that joined that fight.

Japan wins the Battle of Midway

Taking place only half a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Battle of Midway was arguably the decisive naval engagement of the Pacific War. The four Japanese fleet carriers — Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū and Hiryū — were all sunk, as was the heavy cruiser Mikuma. Japan would not be able to recover from the loss.

Had the battle gone differently, Theodore F. Cook and Forrest R. Lindsey speculate that the outcome could have been disastrous for the United States in “Our Midway Disaster: Japan Springs a Trap, June 4, 1942,” published in What If? The World’s Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been, and “Nagumo’s Luck: The Battles of Midway and California,” published in Rising Sun Victorious.

Lindsey argues that defeat at Midway would have forced America to sacrifice its “Europe first” strategy and defend the West Coast. It successfully fights off Japanese attacks on Panama, Pearl Harbor and San Diego and eventually still wins in the war.

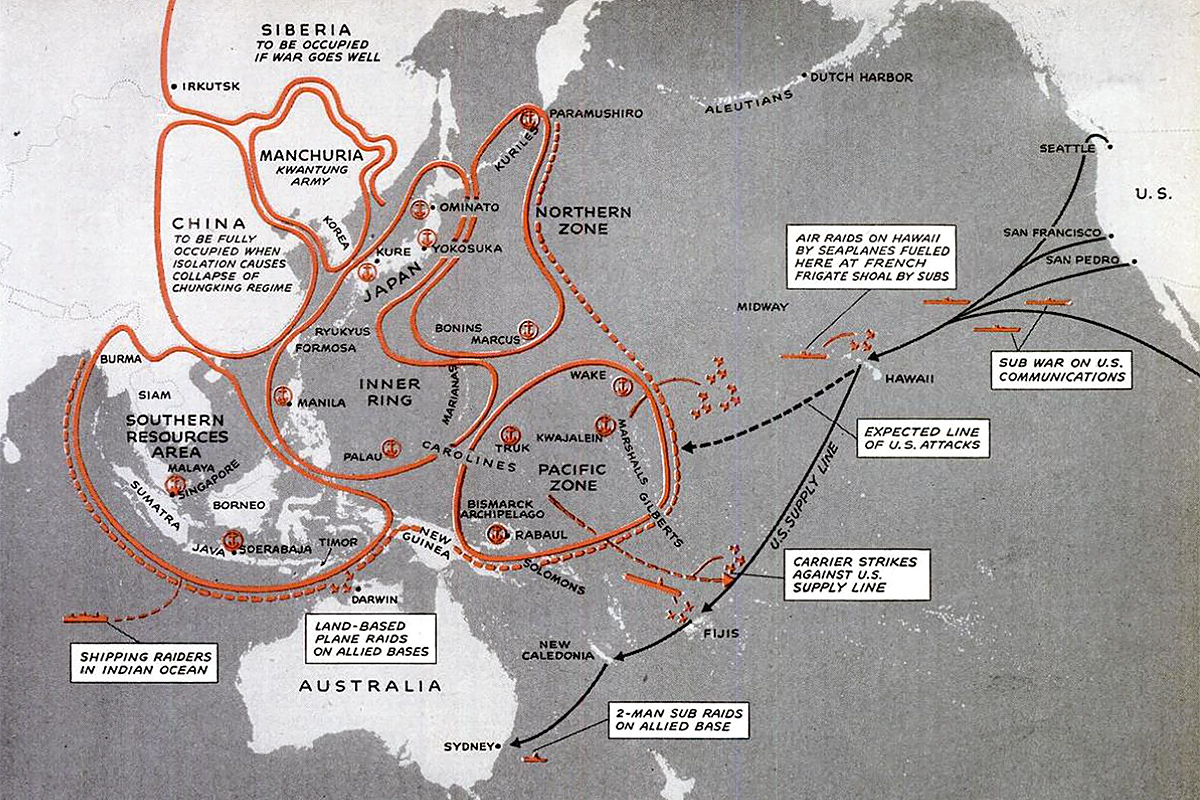

In the real world, Japan never had any designs on the continental United States. Life magazine knew this as early as December 1946. The attack on Pearl Harbor was only meant to immobilize the American fleet so the Japanese could take the Philippines, Guam, Singapore, the East Indies and Wake Island.

Then the Japanese thought they would have time, behind their outer defenses, to exploit their new “southern resources zone” for raw materials which they needed to complete their hopelessly deadlocked war in China.

When the war went better than expected, Japan’s leaders, shocked by the 1942 Doolittle Raid on Tokyo, miscalculated: they extended their defensive perimeter to include Kiska, Midway, New Caledonia and all of New Guinea.

“This rash decision cost them most of their carriers and air force,” leaving the empire vulnerable once the United States had fully mobilized.

Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson use defeat at Midway as the beginning of an elaborate alternate history in MacArthur’s War: The Invasion of Japan (2007). Douglas MacArthur sidelines Admiral Nimitz and FDR, troubled by low approval ratings, a desperate Congress and an unsuccessful Manhattan Project, allows him to carry out his preferred Pacific War strategy, which focuses on capturing the Philippines, Iwo Jima and the Japanese home islands.

Allied invasion of Southern France

In the real world, the Western Allies didn’t invade the south of France until two months after D-Day. Churchill had argued against it, preferring a simultaneous invasion of the oil-producing regions of the Balkans, but this was vetoed by Stalin, who considered Southeastern Europe to be his sphere of influence. The Free French, by contrast, pushed for an invasion of southern France and by July the ports of Normandy could no longer handle Allied supply needs.

What if the Allies had prioritized the liberation of France and attacked from the south?

In Second Front: The Allied Invasion of France, 1942-1943: An Alternative History (2014), Alexander M. Grace has the Allies negotiate with Vichy France for a safe landing on the Mediterranean coast as early as 1942.

The Germans, distracted in Stalingrad, are slow to react. By the time Erwin Rommel is dispatched to stop the Allied invasion, George Marshall and George Patton are already moving their troops, joined by the French, up the country. With losses mounting in the East and West, German military leaders start thinking of ways to get rid of Hitler.

William Jackson imagines a broader Southern Europe strategy in “Through the Soft Underbelly: January 1942-December 1945,” published in The Hitler Options. The Allies expand the 1943 invasion of Italy and simultaneously land troops in Greece, thereby persuading Turkey to attack Nazi-allied Bulgaria. The British invade Yugoslavia in January 1944 and the Americans land in southern France in June. Finally, a joint American-Commonwealth force lands in Pas de Calais in August. The European war ends in December 1944.

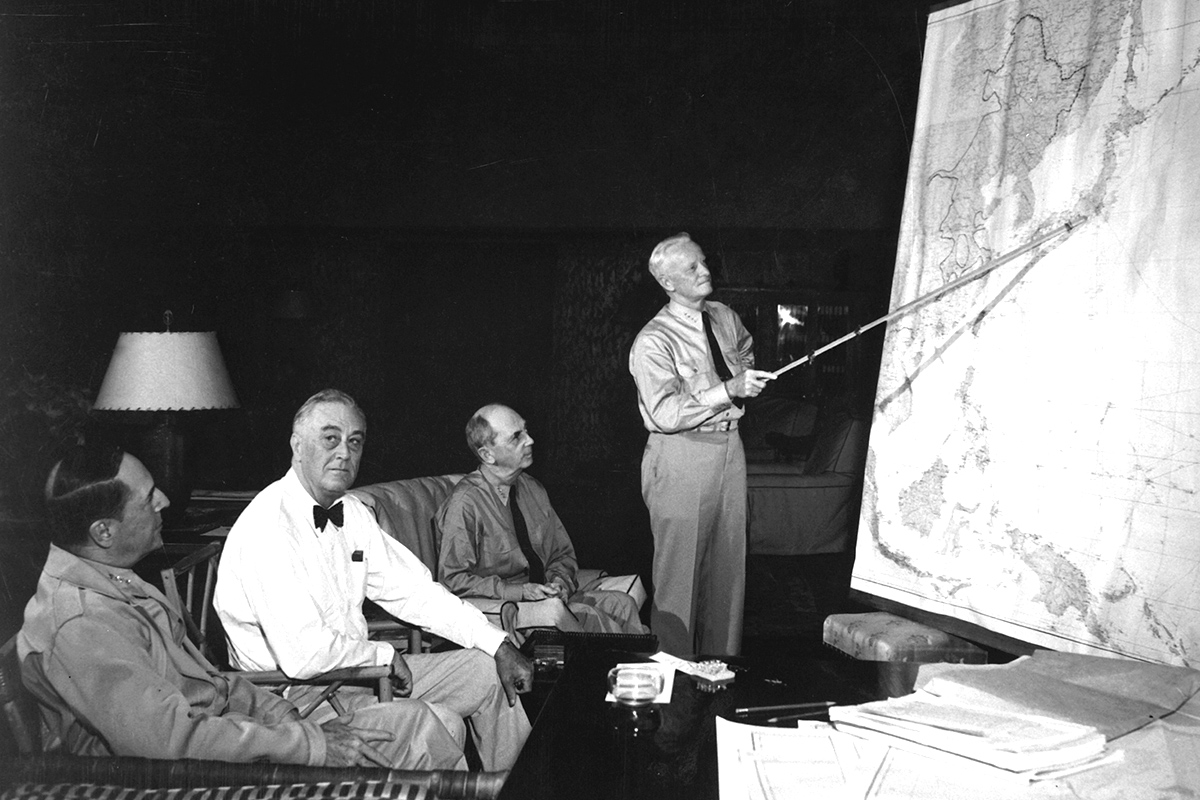

Roosevelt dies at Tehran

There are two ways to kill FDR at the Tehran Conference of 1943. One is medical. The president was said to have suffered a “digestive attack” while meeting his British and Soviet counterparts at the wartime conference. His doctors eventually decided it must have been the flu, although there were rumors of poisoning.

The other option is more sinister: there really was a Nazi plot — according to the Soviets, anyway — to kill all three leaders at Tehran. The Western Allies were skeptical of the intelligence and Otto Skorzeny, the SS officer who was allegedly in charge of the operation, wrote in his memoirs after the war that an assassination attempt had only been briefly discussed and dismissed as unfeasible.

That hasn’t stopped the Russians from dramatizing the plot in fiction. The most famous example is the 1981 French-Soviet film Teheran 43.

If it’s just Roosevelt who died, the effect on American policy could have been profound, as Alasdair Wilkins writes at io9: Henry A. Wallace, the vice president, was (at the time) pro-Soviet. (It wasn’t until the early 1950s that Wallace recognized the Soviet Union for the totalitarian dictatorship it was.) A President Wallace might have been less insistent on Russia joining the war against Japan and more lenient at Yalta, where the three powers effectively split Europe into American- and Soviet-aligned blocs.

D-Day disaster

To create an Allied disaster on D-Day, most alternate histories put Rommel in northern France instead of at home celebrating his wife’s birthday, enabling him to orchestrate a more effective German response. Examples include Peter G. Tsouras’ Disaster at D-Day: The Germans Defeat the Allies, June 1944 (1994) and Tim Kilvert Jones’ “Bloody Normandy: The German Controversy,” published in The Hitler Options.

Tsouras also grants Rommel’s request for an extra Panzer division. Jones argues that the Germans could have been more successful in repelling the Allied invasion if Hitler had been persuaded that the Normandy landings were the real thing and not a diversion.

Matt Mitrovich of Alternate History Weekly Update cautions against making an Allied defeat on D-Day a decisive moment in the war. The Soviets had already pushed the Germans back into Central Europe and the Americans and British were moving north in Italy. The war would have continued, perhaps with the Soviets advancing farther west and the Americans using the atomic bomb to force Germany’s surrender.

American politics could have taken a different turn, though. Dwight Eisenhower may have resigned after a failed D-Day and almost certainly wouldn’t have run for president in 1952. The Republican non-interventionist Robert A. Taft or the Democrat Adlai Stevenson would have been president at a crucial time in the Cold War.

Hitler is killed

We’ll take one kill-Hitler scenario: what if the July 20 plot, dramatized in the 2008 film Valkyrie, starring Tom Cruise, had been successful?

It was the most elaborate of almost two dozen attempts on Hitler’s life since his rise to power in the early 1930s. Among the conspirators were former army chief of staff Ludwig Beck, who was supposed to take over as German president; the deputy chief of military intelligence, Hans Oster; and Claus von Stauffenberg, who planted the bomb in Hitler’s East Prussian headquarters.

Von Stauffenberg was supposed to leave two bombs, but he didn’t have time to activate both. Two bombs almost certainly would have killed Hitler, but it wouldn’t have guaranteed the success of the coup. In the alternate histories Fox on the Rhine (2000), by Douglas Niles and Michael Dobson, and Der 21. Juli (2001), by Christian von Ditfurth, Hitler is killed but Himmler ends up as Führer.

In Fox on the Rhine, Rommel, who in reality sympathized with the plotters and was forced to commit suicide, retains command of the German forces in the West. Under his leadership, the Germans turn Belgium and northern France into one large tank battlefield, climaxing in a very different Battle of the Bulge.

In the sequel, Fox at the Front (2003), Rommel surrenders to the Western Allies in hopes of preventing a Soviet occupation of Germany. With Rommel’s troops now fighting on his side, General Patton beats the Russians to Berlin.

This scenario is not entirely far-fetched. Weeks before the end of the Second World War, British strategists came up with a plan, called Operation Unthinkable, for a war with the Soviet Union. It envisaged 100,000 Wehrmacht soldiers joining American and Commonwealth forces in liberating Poland. Click here to learn more.

Germany refuses to surrender

In the final months of the war, rumors spread that the Germans were preparing to make a final stand in the Alps. A sprawling national redoubt, called the Alpenfestung, was allegedly being prepared for a protracted effort to save National Socialism from defeat.

Time magazine reported in February 1945 that top Nazi officials, accompanied by Hitler Youth fanatics and dedicated SS officers, were planning to retreat, “behind a loyal rearguard cover of Volksgrenadiere and Volksstürmer, to the Alpine massif which reaches from southern Bavaria across western Austria to northern Italy.”

Life magazine similarly reported two months later, mere days before Hitler shot himself in Berlin, that the German army was “wheeling back toward the best defensive positions in Europe, the Bavarian and Austrian Alps.” Salt mines in the area had been converted into war factories, producing guns, fighter planes and gasoline, it said. “There were said to be subterranean hangers, tremendous depots of coal, grain and foodstuffs.”

Some of this was true. There really were underground factories and some fortifications were made. But most of it was Nazi propaganda.

What if the Alpenfestung was real and Germany refused to surrender?

Thomas Ziegler images in Die Stimmen der Nacht (1984) that a still-alive FDR would have ordered a nuclear strike on Berlin to force the Nazis to give up.

In Harry Turtledove’s The Man with the Iron Heart (2008, our review here) and Robert Conroy’s Germanica (2015), Nazi hardliners wage a Werwolf insurgency against the Allies from their mountain stronghold. In the former they are led by Reinhard Heydrich, in the latter by Joseph Göbbels.

Click here to learn more about the German national redoubt that wasn’t.

Japan refuses to surrender

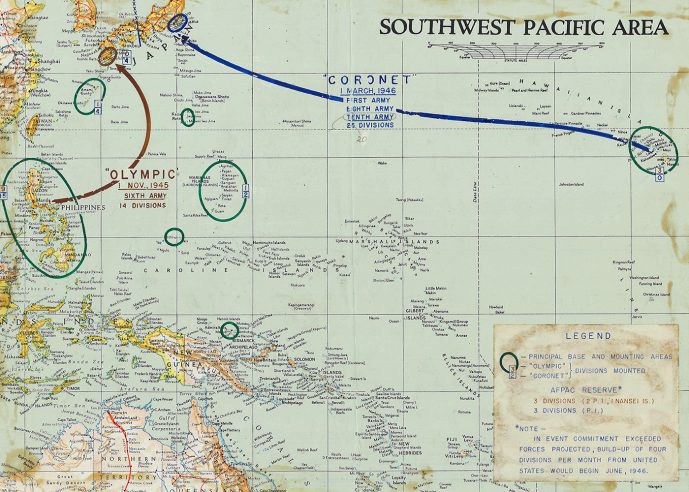

What if Japan had refused to surrender? Before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it certainly had no intention to. Japan’s leaders knew that they could no longer win the war, but they planned to make the cost of invading and occupying their islands so high as to force to Allies into an armistice. The entire Japanese population was called upon to resist the “white devils”. American military leaders estimated that the invasion, codenamed Operation Downfall, could cost between half a million and a million Allied lives.

If the Trinity nuclear weapons test in July 1945 had been a failure, and no nuclear weapons were available to force Japan’s capitulation, then Downfall would almost certainly have been carried out.

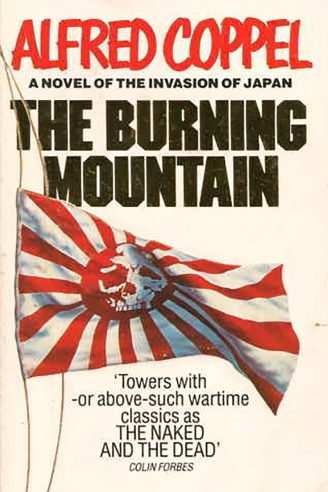

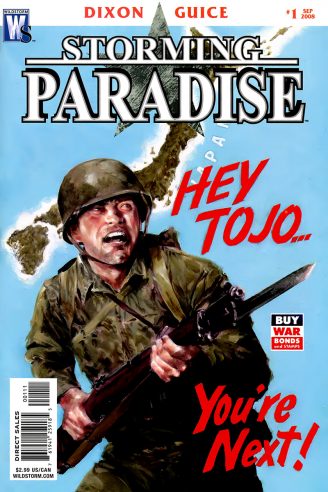

It is in Ronald W. Clark’s The Last Year of the Old World (1970), Alfred Coppel’s The Burning Mountain (1983) and the Storming Paradise comic book series (2008-09), written by Church Dixon.

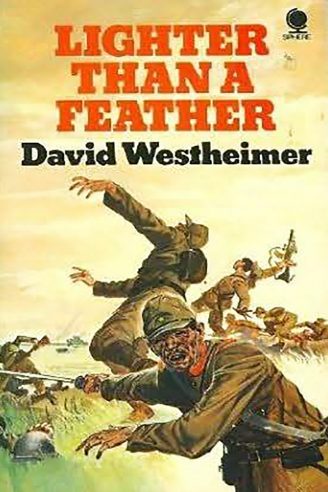

David Westheimer’s Lighter than a Feather (1971) is written from the perspective of a soldier taking part in Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyushu. The other half of Downfall, Operation Coronet, was the planned invasion of Honshu.

In Robert Conroy’s 1945 (2007), America develops and uses atomic weapons but Japan simply refuses to surrender, leading to a bloody war of attrition and Vietnam War-style protests in the United States.