On the eve of America’s entry into World War II, George Fielding Eliot reported for Life magazine that the country essentially had three ways to defend itself against an Axis invasion.

He rejected the first option, a purely defensive strategy, out of hand. Protecting just the United States, the Caribbean, the Panama Canal and Samoa, but not Canada, Greenland, Newfoundland and South America, would allow Germany and Japan to gain footholds in the Americas.

The whole of military history rises up to warn us that this is the inevitable prelude to defeat.

The choice, he argued, was between hemisphere defense and sea command.

Hemisphere defense

This would make the best use of distance, which Eliot argued was in America’s favor, and cover its deficiencies in terms of time.

If we are given enough time, we can make ourselves so formidable in this hemisphere that no combination of powers would dare attack us. But if we are attacked tomorrow, we may be in bitter difficulties.

The subsequent history of the Second World War would bear that out.

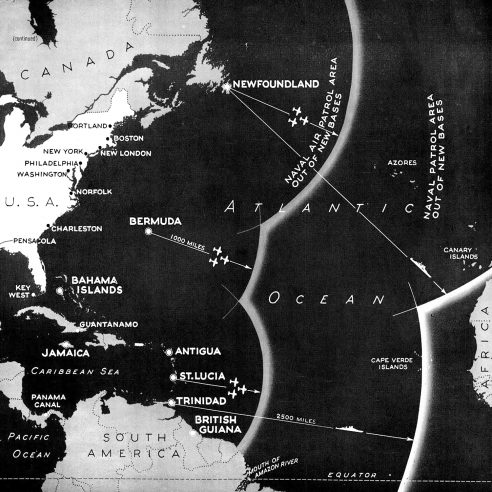

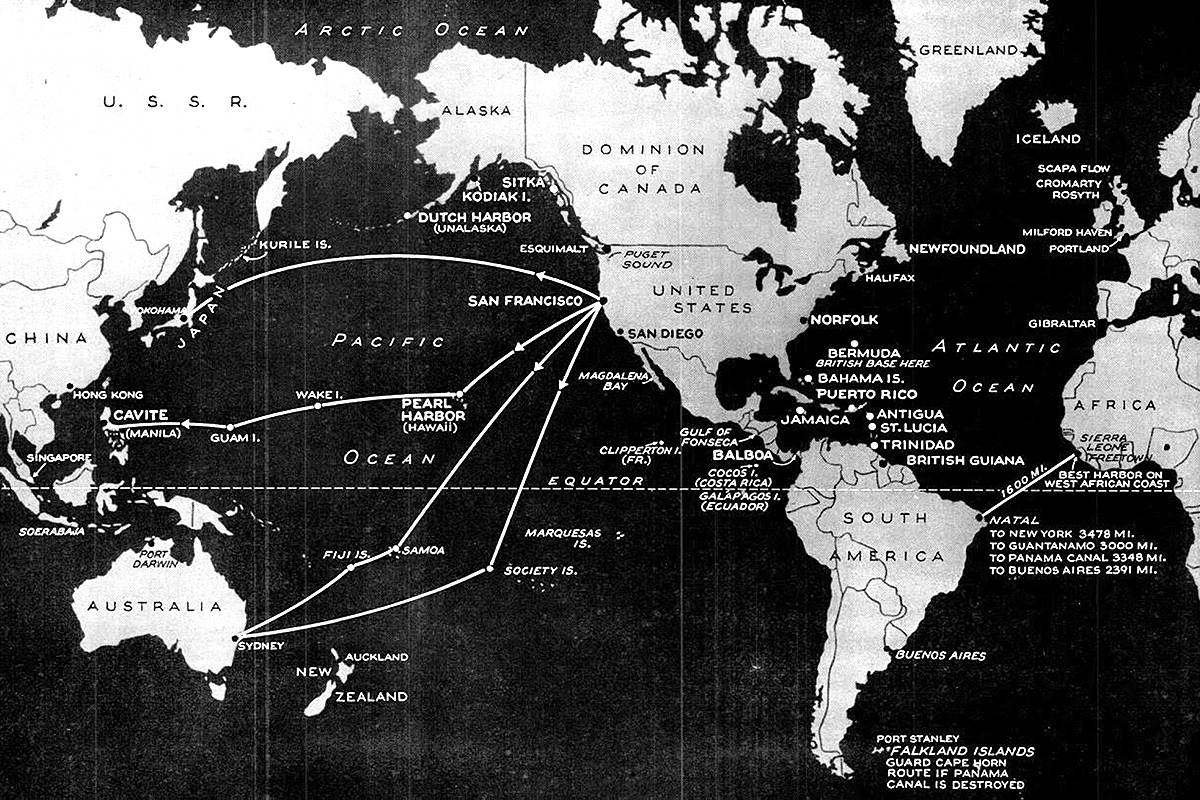

To deter a German invasion, Eliot called for military bases in Newfoundland (then not yet part of Canada), Greenland, Bermuda and northeastern Brazil and ideally the Azores and Cape Verde as well.

With the exception of Brazil (a site in British Guyana was chosen instead) and Cape Verde, America would establish bases in all those places — and in many cases maintain them all throughout the Cold War.

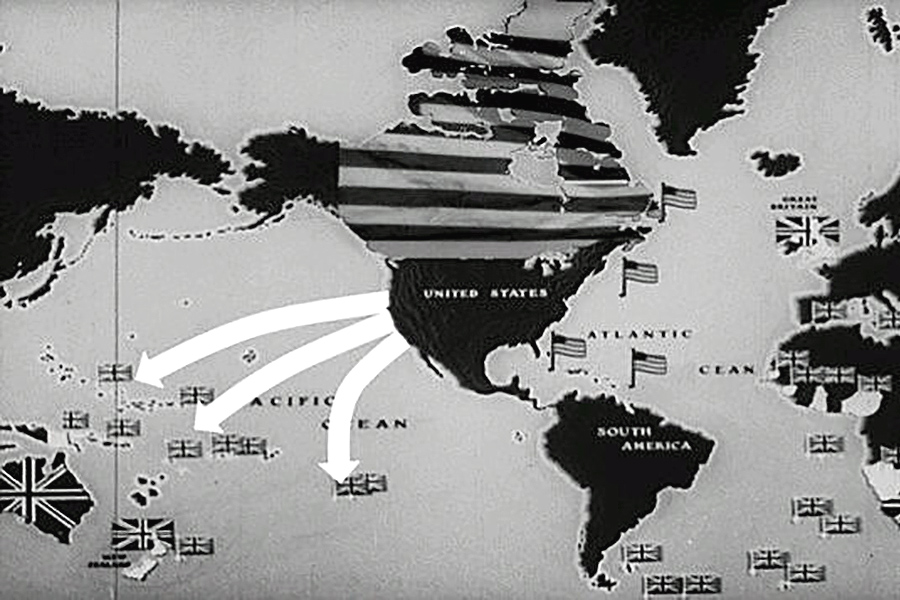

Command of the seas

The more ambitious — and in Eliot’s view the superior — strategy was to attempt command of the oceans.

America was already dominant in the Pacific. To control the Atlantic, Eliot called for an alliance with Britain and its dominions: Australia, Canada, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa. Without the British Fleet, he warned, America’s naval forces would be stretched thin.

That is the strategy America chose — and arguably the one it maintains to this day.