The dystopia is a familiar trope in the “Piecraftian”, darker side of dieselpunk.

Erika Gottlieb argues in Dystopian Fiction East and West: Universe of Terror and Trial (2001) that dystopian fiction looks at the totalitarian dictatorships of the dieselpunk era as its prototype: “a society that puts its whole population continuously on trial, a society that finds its essence in concentration camps, that is, in disenfranchising and enslaving entire classes of its own citizens, a society that, by glorifying and justifying violence by law, preys upon itself.”

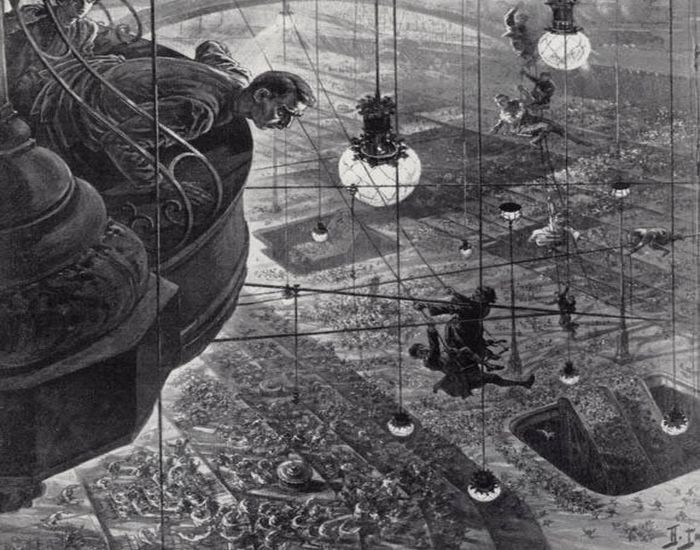

One of the earliest dystopias comes from that great fountainhead of science-fiction, H.G. Wells. In his 1910 novel The Sleeper Wakes, our hero — a confirmed Marxist who falls asleep in Victorian Cornwall — wakes up in London two centuries later to discover that, owing to a trust-fund set up by his brother, he is now the ultimate capitalist and owner of half the planet. Wells describes a technological wonder world with aeroplanes, radios, televisions and automatic tailors. Old landmarks like the Houses of Parliament and St Paul’s Cathedral are tucked away in the basement. The Thames has become an underground canal.

So far, so good — but we gradually discover that the corporation ruling in our hero’s name is far from benevolent and a third of the population lives in virtual enslavement to an organization descended from — wait for it — the Salvation Army!

The urban dystopia more familiar to dieselpunks will be Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. A technocratic utopia on the surface, with sky scrapers the size of small cities and sky bridges crisscrossing the bottomless concrete canyons, the futuristic city only runs on the labor performed deep below by workers without rights nor any hope of a better life.

As Piecraft himself has written, the 1927 German film is really a precursor to the dieselpunk genre. The “large factories, big pumping machinery and other forms of radical technology and science that at the time of the film’s making were but pure fantasy” have inspired similarly depressing industrial landscapes in later dieselpunk fiction. Metropolis‘s theme — a world radically changed, and not for the better, by war or a cataclysm — is one that resonates in the darker side of the genre today.

In this case we recognize that Lang seeks to show us the dire consequences of a war out of which a totalitarian regime emerges victorious. This brings about a world in which the freedom and happiness of the masses are compensated in order to stabilize peace.

Which goes to the essence of the dystopia.

George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) is the most famous example. It introduces a world where surveillance is so omnipresent that even thinking the wrong thoughts can be cause for persecution. In “With Folded Hands …” (1947), Jack Williamson has robots take over to prevent humanity doing any harm to itself. Recurrent themes include an all-powerful state and no hope of ever regaining what has been lost.

Or is there? The dystopian London of Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta is not too dissimilar from Orwell’s. But this time our hero isn’t beaten by the system. The anarchist “V” manages to topple a Nazi-like dictatorship by challenging the tradeoff people made in the first place: After nuclear war, the British accepted tyranny as the price for security. Some, like “V”, never will.