In order to begin analyzing dieselpunk as a serious genre within the literary world of fiction, it is necessary to realize its development from steampunk as well as cyberpunk, both to which dieselpunk owes a lot, as well as from pulp comics and literature published throughout the 1930s, 40s and 50s.

The term that was first coined by Lewis Pollak to describe the fantastical setting of his Children of the Sun became a definitive choice word to encapsulate a form of science-fiction that starts with the end of the Roaring Twenties through to the beginning of the Cold War, culminating primarily with the Red Scare of the era and its dread of a nuclear Third World War.

This newfound genre gained further notoriety on the Internet among fans of pulp-orientated literature and buffs of neo-noir cinema. Elements from both enhanced the genre’s anachronistic setting within a realm that combined the advanced and somewhat dystopian aspect of the 1930s with an overabundant use of Art Deco and Futurist outlook in style and design.

Yet even nowadays the term has hardly been recognized by peers of science-fiction — unlike steampunk and cyberpunk — because dieselpunk has yet to officially spawn more original material than the Children of the Sun role-play.

The idea of dieselpunk

What I seek to demonstrate in this article is how the “idea” of the dieselpunk setting has long existed within fiction, much like its predecessor steampunk.

It were the visionary imaginations of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells that inspired steampunk’s purpose in a post-modernist literary world crying out for nostalgic revival supplemented with a touch of cynical worldviews. Steampunk grew in the ranks of seminal, alternative fiction over time, yet has remained very much true to the conscious mind of readers and writers of the fantastic adventure genre of the turn of the century — a genre that, until now, had no proper name.

And much like the predecessors and purveyors of steampunk discussed a future of steam-powered technology and optimism and adventure during the sometimes crisis and despair of the Victorian era, so dieselpunk also will become accepted eventually in the same respect.

Notable precursors to the dieselpunk genre encompass the very same themes and ideas expressed in steampunk — ransposed into the 1930s.

We find a tumultuous time in which society has not recovered entirely from the horrific experiences of the Great War, yet one in which the threat of another war seems ever present.

It is also a time in which the dirtier and grittier aspects of an advanced technocratic society become apparent and accepted.

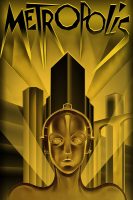

Metropolis

There are two significant works of period fiction, very different in story and scope, which together perfectly demonstrate the converging dichotomy found in the dieselpunk world of the Interbellum — the period that forms perhaps the definitive setting for dieselpunk fiction.

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927), although set in a distant future, beyond the typical timeframe of dieselpunk, makes for an excellent example of the genre’s style and technology as prevalent in a future dystopian society: large factories, big pumping machinery and other forms of radical technology and science that at the time of the film’s making were but pure fantasy, emphasized by German Expressionism. The design and setting of the cityscape represent the Futurist style of the dieselpunk setting.

Altogether, Metropolis perfectly exemplifies the “Piecraftian” dieselpunk, one that predicts the darker and despairing outcome of a world changing event, be it a war or cataclysm. In this case we recognize that Lang seeks to show us the dire consequences of a war out of which a totalitarian regime emerges victorious. This brings about a world in which the freedom and happiness of the masses are compensated in order to stabilize peace.

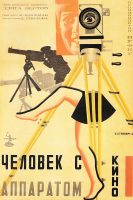

Man With A Movie Camera

Man With A Movie Camera (1929), directed by Dziga Vertov, is a depiction of the urban-industrial life in the Soviet-Russia of the 1920s.

The film represents a vision of progression as it portrays the enthusiasms and hopes of a society emerging from a worn and weary past and now confident about its future. Citizens are shown at work and at play, interacting with the machinery of their modern world. The visuals possess a raw element of experimentation, involving stop-motion animation as well as montage to evoke the spirit of the times and cast an entirely idealistic outlook of society in Odessa and other Soviet cities upon the rest of the of the world.

Vertov portrays his story in a quasi-observational documentary style, even incorporating elements of propaganda filmmaking to the simplistic narrative. To the extent that it can be said to have “characters”, the film interacts with the perspectives conveyed by the allusive Cameraman of the title and the modern Soviet Union he discovers and presents in the film.

This example perfectly fits the “Ottensian” dieselpunk as a hopeful and excited view of the modern world that emerges from the ashes and suffering of the past and is invigorated by the radical advances of technology and science.

Influence on dieselpunk

Although the two films are completely different and were never intended to be considered dieselpunk, their imagery and themes have inadvertently influenced dieselpunk culture.

Metropolis is a film that questions technocratic and societal class issues within the frame of science-fiction. The unique style of German Expressionist mise-en-scene evokes the fantastical and seems to place the events of the film beyond any time we could possibly relate to.

However, it is the underlining story which harkens our consciousness to the issues of totalitarianism and class struggle — which were ironically carried through to the 1930s up until the 1960s, when civil liberties were finally recognized for every man and woman. The film was made in 1929 before the Second World War, but was perhaps reverberating the effects of the Great War that were still fresh in the minds and had left scars on many around the world.

Man With A Movie Camera was made in the same time as Metropolis, yet with a very different purpose: to document life under communism. A new world was opened to Russian eyes after the revolution; people were no longer struggling to live, for everyone was considered an equal in Lenin’s state. The film represents confidence in a social system that was still in its early stages at the time.

Through it, we garner an optimism about a future which seems to have no bounds. One is excited by the great improvements made to society, by the pushing of boundaries of a strong industrial nation that is exploring new concepts and ideas about technology and society and also a nation that perpetually oils the gears of the machine-state that will lead it to greater heights.

Unlike Metropolis, Man With A Movie Camera promotes an enthusiasm that people were not to dwell morbidly on the war and regime of the past, but that they would improve their situation by working harder and moving faster and further to unknown reaches for the benefit of all involved.

Precursors to the genre

What makes Metropolis and Man With A Movie Camera precursors to the genre?

Not only do they evoke the experience of the era in which dieselpunk is set; they also promote two very different ideals which were fictionally drenched in fast-forward thinking dreams for science and society — both with an important socio-political message.

Both films illustrate the new and the upcoming technologies of the Interbellum, for at the end of every war breakthroughs in science are brought to public awareness. A race for arms and the previously unexplored carried on even into the Second World War and the Cold War; and with it came the increasing production of consumer products, be they automobiles, telecommunications or fashion.

So it is acceptable to acknowledge that throughout the 1930s, 40s and early-50s, the world was constantly changing politically and technologically, spawning new advances in culture and science. This highly unstable period that was in a flux of progressing toward greater power in both a technologic as well as a political aspect brought about many great social crises and awakenings, reinforced, of course, in the very films which were at the time prophetic in their own analyses of the times.

But because neither film embodies dieselpunk absolutely, they can only be seen as precursors to the genre. They can be considered as strong influences to the genre, just as Jules Verne and H.G. Wells relate to steampunk and George Orwell’s 1984 and Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville to cyberpunk. And just as in steampunk and cyberpunk, many of the themes and designs and imagery found in these films, have been adopted into the dieselpunk setting, influencing other works which have become generally accepted over time as existing within the known genre.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 3 (November 2008), p. 14-16, with the headline “The History of Dieselpunk, Part I: Proto-Diesel”.