The years following the collapse of Wall Street in 1929 were some of America’s most iconic with regards to the dieselpunk genre. While the Roaring Twenties tore us away from the moorings of Victorian culture and the 1940s saw Uncle Sam fighting toe to toe against the Axis, many of the sights and sounds that we associate with dieselpunk are actually products of the 1930s.

The age of skyscrapers and the start of the sprawl

Flocking from the small towns of the Midwest, out-of-work families flooded the urban centers of Chicago, New York and the other metropolises of America looking for better lives. What they found was more of the same — unemployment, poverty, dust storms — but this migration cemented the city as the primary locale for America’s population (as opposed to the rural) for the first time in history.

Of course, this concentration of people lead to expansion and triggered the birth of the sprawling mega-cities seen today; a common trope in cyberpunk, dieselpunk and related punk fiction. The megacities and their newly planted skyscrapers (Bank of Manhattan Trust in 1930, Empire State in 1931, etc.) became the beacons of hope in America, despite the fact that there were scores of people starving to death in the neon canyons below.

White hats and black hats

Looking back at the thirties through the spyglass of history, certain trends peek through. Whether it’s due to “creative” journalism moreso than fact, America had more than its share of white-hat “good guys” and black-hat “bad guys” in the limelight at the time.

The everyman living in the city was just a bit player compared to notorious gangsters like John Dillinger and their G-Men counterparts in the fledgling Bureau of Investigation. During the 1930s, each side was painted as being larger than life. Dillinger’s face was in every cheap detective pulp as America’s “Public Enemy No. 1”, while at the same time, the urban folklorists portrayed him as being a Depression-era Robin Hood who only stole from the rich.

On the flip side, J. Edgar Hoover’s agents were seen as straight-laced and top-button knights charged with saving America from the plague of crime (if it said so in the serials, then it had to be true).

During the early thirties, there was no room for Regular Joe in the public eye anymore, but that all came to an end in 1933-34 with the death of Prohibition and Dillinger respectively.

As a matter of fact, 1934 alone saw the rise and fall of Bonnie and Clyde, Pretty Boy Floyd, Baby Face Nelson, Red Hamilton and other pinstriped ghosts that still haunt the pages of dieselpunk and crime fiction today.

The underdog fights for his livelihood

While the Depression forced some people into the arms of organized crime, others banded together to get what was owed to them.

In 1932, a literal army of 43,000 World War I veterans and their families marched on Washington demanding early payment for their war time contracts (not to be fulfilled until 1945). Starving and out of work, the “Bonus Army” set up camp and rallied around the nation’s capital, even going so far as to create their own military-organized town in the woods surrounding Washington.

Despite their camps being razed by tanks and infantry guided by General Douglas MacArthur (against the orders of the president, I should add) and dozens being killed or injured during the resulting battle, the Bonus Army finally received their due in 1936 and won a victory for the little guy when he needed it most.

The seeds of nationalism

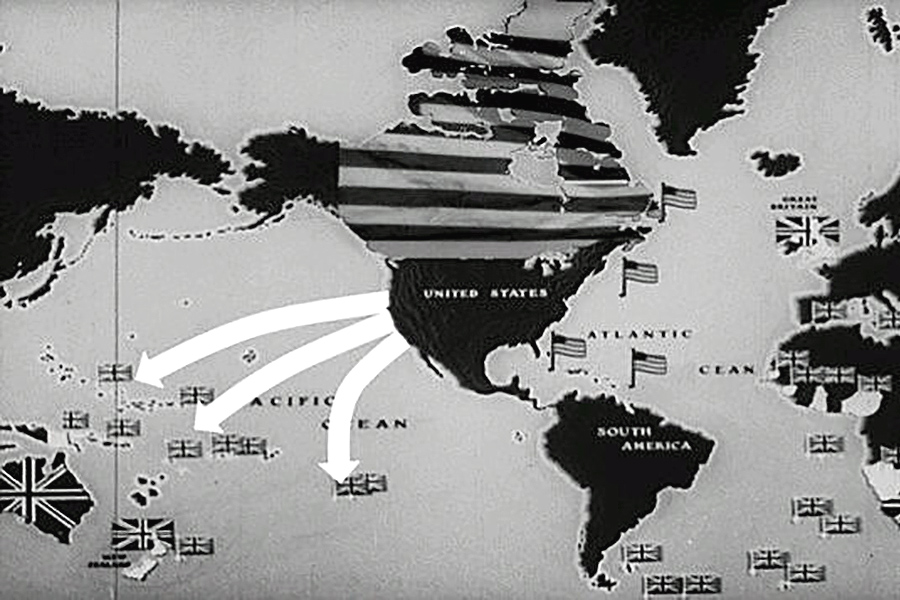

When Wall Street collapsed, it sent ripples around the world, toppling over countries that were finally healing from the Great War. We already know about Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and the workings of “His Excellency Benito Mussolini, Head of Government, Duce of Fascism, and Founder of the Empire” (as he was known during the late 30s), but America fell on a jingoistic crutch as well. As a kneejerk reaction to the 1929 crash, President Herbert Hoover effectively taxed international trade out of competition with national goods thanks to the H-S Tariff in 1930.

It was certainly an “every man for himself” age. Even Lady Liberty was closing her gates in favor of her children. An age of paranoia began and the flag waving cries of “America First” were heard from coast to coast.

Swingtime and interracial community

At the Cotton Club you could jitterbug to the child of African-American jazz music known today as “swing music.” The kids went crazy for the sounds of Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Duke Ellington, Artie Shaw, Cab Calloway and Chick Webb with vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday and Peggy Lee at the ready to keep America dancing after dark.

Unlike anything else, swing is the iconic soundtrack of the 1930s, because it not only spread around the Western world and was the most popular music at the time but because it also triggered an age of whites and blacks coming together in relative peace for the first time in America.

While this peace wasn’t always a dream, the halls of Big Band music housed the ideas of tolerance and started a bigger change in America that we still benefit from today.

Age of the airship

Until the Hindenberg disaster in New Jersey, airships were a real, luxurious form of travel, not unlike today’s cruise ships.

The dream of powered flight born of the 1900s and steeled during the Great War was in its prime in the 30s, giving birth to reliable airplanes and sturdy dirigibles more than capable of international travel (a fact proven by heroes like Lindbergh and Earhart in the late 20s).

Combined with skyscraper docks for airships in New York and other mega-cities, today’s world could have surely lived up to our dreams of Metropolis and Gotham. Had it not been for Germany’s lack of helium, the matchstick of fate would have never ignited humanity’s fear of these great machines and ruined our chances for a sky-filled future.

Unless we build the future now, we won’t be alive to enjoy it

The 1930s saw two World’s Fairs that focused the nation’s energies into dreaming of a better tomorrow.

The first, Chicago’s Century of Progress in 1933-34, would never have been built if it weren’t for the readily available laborers looking for work. It showcased the world of tomorrow; a world at peace with itself and open to the idea of the future not just as a progression of time, but as a goal to be achieved.

Take this quote from the 1939 World’s Fair in New York for example:

The eyes of the Fair are on the future — not in the sense of peering toward the unknown nor attempting to foretell the events of tomorrow and the shape of things to come, but in the sense of presenting a new and clearer view of today in preparation for tomorrow; a view of the forces and ideas that prevail as well as the machines. To its visitors the Fair will say: “Here are the materials, ideas and forces at work in our world. These are the tools with which the World of Tomorrow must be made. They are all interesting and much effort has been expended to lay them before you in an interesting way. Familiarity with today is the best preparation for the future.”

While the New York World’s Fair was a financial nightmare as a business venture, it succeeded in its goal of bringing the future to life inside a temporary utopia. Not unlike Disney’s EPCOT Center two decades later, the 1939 World’s Fair served as a cultural showcase and as a model for how different countries could learn from one another and work together even as the tide of war crashed against these ideals in the real world.

These are just a few of the tropes used in dieselpunk, but as you can see, the 1930s were a time when the ideas of the 20s were forced into reality. The market crash stopped the party and put America back on the tracks (for better or worse). Had it not been for the Second World War, the dieselpunk future could have easily been the world we live in now.

That doesn’t mean it’s gone; it just gives us a better world to work toward today.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 19 (July 2011), p. 4-5, with the headline “Surviving the 1930s”.