The era of steampunk ends with the First World War. While authors have played with twilit eras of brass and steam existing deep in the twentieth century before, these tend to be aberrant epochs, places where the life of the Gilded Age has been unnaturally prolonged. When the war breaks out, as it does in Ian R. MacLeod’s House of Storms (2005), and as it is implied to do in Stephen Baxter’s Anti-Ice (1993), it symbolizes the end of an age, the final verdict of a world too frivolous to last, yet too innocent to deserve the coming judgment.

However, Scott Westerfeld, a specialist in young-adult science-fiction, who made his mark with the popular Uglies series, has taken a different tack. Rather than positioning the Great War as the end of steampunk, Leviathan imagines a war that has been colonized by the steampunk aesthetic.

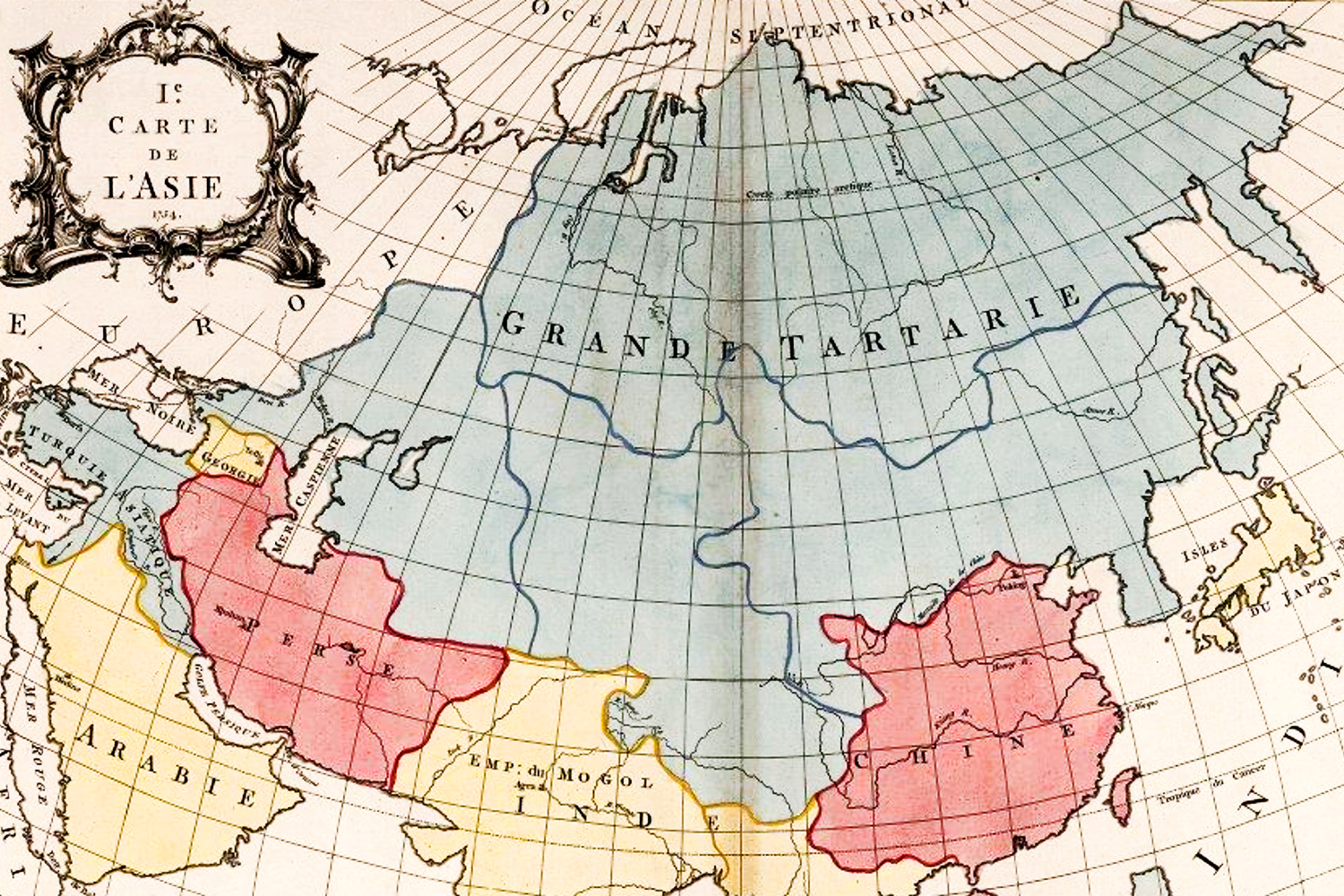

While conflict breaks out in August 1914 upon the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, it is not one between monarchs, empires or markets, but between industrial ideologies.

On one side are the “Darwinist” empires of Britain, France and Russia, which, thanks to the discovery of DNA by Charles Darwin in the 1860s, have created societies powered by artificially-created lifeforms.

Arrayed against them are the “Clanker” powers of Central Europe and the Middle East, which have taken a hyperindustrial route to power, with fleets of airships and heavily armored walkers prowling the forests. (The arsenals of both sides are beautifully rendered by the magazine serial-inspired sketches of Keith Thompson, which flit about the book.)

To guide the reader through his world, Westerfeld relies on a number of archetypes and plotlines familiar to any reader of period adventure fiction and to any reader of steampunk, in fact.

The Clanker side of the conflict is explored by Aleksandar von Hohenberg, allohistorical son to the late archduke, who is forced to flee into the Austrian wilderness with a loyal retinue and a small stormwalker after catching wind of a German conspiracy against his life.

The Darwinists, on the other hands, are represented by Deryn Sharp, a classic girl in midshipman’s clothing swept into a mock-Napoleonic sailing/zeppelin story aboard the titular HMAS Leviathan, a great aerial whale carrying an ecosystem of offensive weaponry.

Westerfeld cleaves quite close to the pulp-adventure roots of his story, with plenty of chases, pitched battles, races against the clock, secret castles, budding romance and secret weapons to go around.

While the story is kept at a brisk pace, some of the characterization and worldbuilding does come off as flatter than an adult reader would expect, with the characters occasionally being overshadowed by the exotic machinery they interact with.

This flatness, however, is alleviated by hints Westerfeld drops of broader forces in his world.

Despite the pulpy exoticism of the struggles between the Darwinist and Clanker forces, there is a very real sense that both sides are fighting blind, with little understanding of how to get a proper handle on their opponents. Akin to our world, both sides have plenty of technology but little doctrine, a flaw made all the more unsettling by the fact that the Darwinists and the Clankers are quite capable of fighting a World War II-esque conflict continent-wide.

While the philosophies of both sides are kept in the dark (though there are intriguing hints that the Social Darwinism of our history has been replaced by a vaguely modern conception of ecosystems and webs of cooperation), the analogy to our history does suggest that the course of the war, and the era of totalitarianism beyond it, could develop in potentially horrifying directions.

As Leviathan is billed as the first part of a trilogy (the second book, Behemoth, is scheduled for release in 2010), Westerfeld will no doubt be coming back to address some of these issues.

As it stands, Leviathan is a solid introductory novel. While not a transcendent work, it sets up a neat little world with the potential for future growth while providing a superb introduction to steampunk for younger readers.

It is not the Great Steampunk Great War novel, but is it an enjoyable romp through a gadget-festooned landscape, a sort of final breath of mechanical irreverence before the coming winter.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 9 (November 2009), p. 10-11, with the headline “Adventures at Armageddon; Review; Leviathan”.

3 Comments

Add YoursLeviathan was a good start to a fine trilogy, though the UK hardcover I bought gave no hint that it was anything other than a standalone novel, apart from the text itself. And Keith Thompson’s illustrations were indeed excellent. I’m pleased extensive illustration has come back into fashion more recently with the Dieselpunk/Steampunk novels Timeless: Diego and the Rangers of the Vastantic and Above the Treeline.

The artwork form Timeless: Diego and the Rangers of the Vastantic — at least what Google image search turns up — looks amazing!

Amazing indeed! And beautifully integrated into the story. There are over 150 large color illustrations.