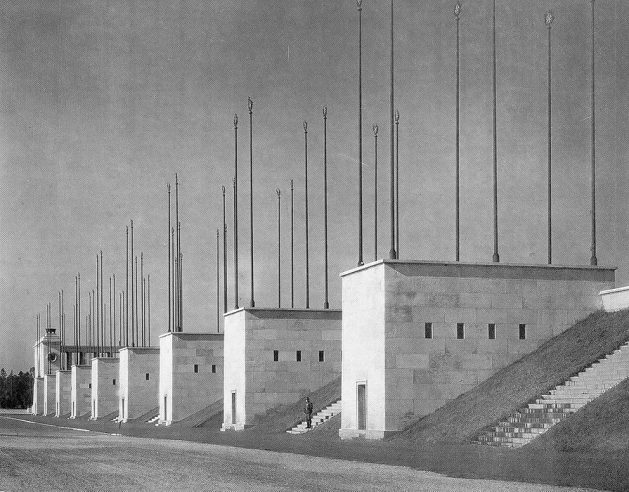

The Nazi Party Rally Grounds in Nuremberg, Bavaria were Albert Speer’s first assignment as Adolf Hitler’s chief architect. The grounds he designed — and which featured prominently in Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda masterpiece, Triumph of the Will — were based on ancient Doric architecture, magnified to an enormous scale and capable of holding over 240,000 spectators.

Zeppelinfeld

When Speer accepted the job, the only building on the grounds was the Luitpold Grove, a park and exhibition area originally built in 1906. The Nazis had expanded and converted it into the Luitpold Arena in the early 1930s for SA and SS ceremonies. A Memorial Hall (Ehrenhalle) was dedicated to the citizens of Nuremberg who had died in the First World War. The building had been designed by Fritz Meyer in 1930, consisting of a hall of arches, two side rooms in which books containing the names of the dead were displayed, and a forecourt flanked on both sides by a row of pillars, each topped with a flat torch bowl.

Speer started by adding a crescent-shaped tribune opposite the Memorial Hall and continued with his first major design for the area: the Zeppelinfeld.

Every year until the outbreak of World War II, the party faithful would gather here for a massive demonstration of Nazi power.

At the 1934 party rally, Speer famously had the site surrounded with 130 anti-aircraft searchlights, creating a “cathedral of light” that inspired a sense of mystery and meaning into the crowd.

The swastika on top of the field’s tribune was blown up in 1945, but the rest of the grounds are still there and open to visitors.

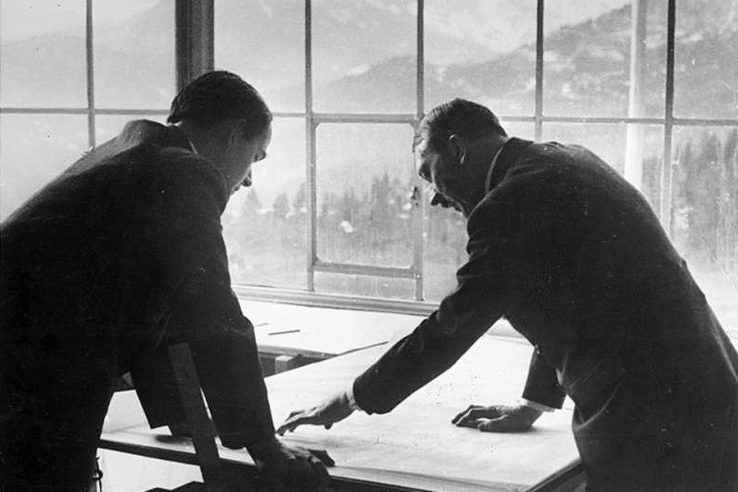

Plans

A much larger parade ground was scheduled for the army nearby, called the Märzfeld. It would have been the size of eighty football fields. Construction started in 1938 but was interrupted by the war.

Work also started on a large sports stadium and congress hall. The latter was supposed to seat 50,000 people. The roof was never built, but the structure, such as it is, now houses a museum.

Ruin value

At Nuremberg, Speer developed his theory of ruin value, which held that all buildings should be so designed as to make aesthetically pleasing ruins thousands of years into the future. In practice, this idea manifested itself in Hitler’s preference for monumental stone construction, rather than the use of steel frames and ferroconcrete.

Speer himself wrote in “Die Bauten des Führers,” published in Adolf Hitler. Bilder aus dem Leben des Führers (1936), that durability was the most important principle of the Nazi regime’s architecture:

The buildings of our Führer will speak of the greatness of our age to future millennia. As the eternal buildings of the movement rise in the various cities of Germany, they will be buildings of which people can be proud. They will know that these buildings belong to everyone, and therefore to each individual. The Führer’s buildings will determine a city’s nature, not department stores, administrative buildings, banks and corporations.

Apparently, the idea that his buildings would ultimately perish did not bother Hitler, although it scandalized his entourage.

4 Comments

Add YoursSpeer’s exteriors are massively ungraceful, looks like Speer was faced with a project titled “Use Concrete”.

I completely disagree, the buildings designed by Speer are perhaps the best examples of real architecture I have ever seen. It’s just a shame that some of these buildings remained as plans and were never built.

I have reassessed my opinion and I decided that I was completely wrong. Although I do not understand what you mean by “real architecture”. This is a style of architecture.

Having recently visited the Zeppelinfields, it is apparent that Speer’s notion of “ruin value” was right in the mark. Only his structures did not last thousands of years. They were already falling apart after a few short decades. Much of the reviewing stand was demolished for reasons of safety. Speer’s and Hitler’s preference for limestone as a construction material did not weather well and would have required a lot of maintenance. The catalog of Nazi architecture was built largely with native limestone.