In a 1973 interview with Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune, French film theorist and director François Truffaut stated, to modest infamy, that “Some films claim to be anti-war, but I don’t think I’ve really seen an anti-war film. Every film about war ends up being pro-war.”

Alternate history is a genre with an image problem. I think this is a fairly uncontroversial statement. With the explosion of interest in alternate history within the media mainstream, from TV shows such as Apple TV’s For All Mankind or even Marvel’s inter-continuity anthology What If? (and recent film Dr Strange 2: Multiverse Boogaloo), we are in a period where alternate history has arguably truly emerged as a “legitimate” genre worthy of both mainstream attention and financial success. But when you ask the average person as to what, exactly, alternate history is, you will not hear of For All Mankind, or What If?. Every alternate historian has instead heard those dreaded words, “oh, you mean like, what if the Nazis won?”

As much as we may cringe at this question, put on a rictus grin, and explain away such associations with fascism, it is undeniable that there is a problem. It seems every other week on Twitter, alternate history circles are caught up in a tiff when someone pointedly critiques the genres perceived obsession with Nazis and Confederacy victory. Indeed, while I was writing this, such a conversation happened, which I will use as an example of its type.

MSNBC correspondent Katleyn Burns tweeted,

Alternative history is always like “what if the Confederacy won?” Or “what if the Nazis had won?” And never “what if all the Southern slaves had murdered all the slave holders?”

Which led to Matt Mitrovich of The Alternate Historian responding:

It frustrates me to see the same tweet: “why is alternate history just about WWII or the American Civil War? Why not about [insert person’s fav what if]? Meanwhile it apparently never occurred to them to Google it and find the dozens of stories people have written.

With all the respect in the world to Mitrovich, who is right that there are many published works of alternate history concerned with matters beyond the scope of that common what-if, and that really it’s not as common as one may think, this reaction does little to address the core frustration Burns’ tweet expresses.

It is easy to write “Google it,” reject the concerns and critiques of the genre and so dismiss the implication being made as historical reenactors may dismiss the crisis of the far right within their own hobby as ignorance. But it is foolhardy to do so.

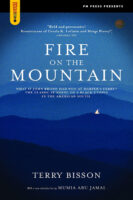

It’s perfectly fine to recommend, say, the excellent Fire on the Mountain, in which the Southern slaves do murder the slaveholders, as many did to Burns, but we cannot stuff Bisson’s novel into our ears as a shield against this problem. We cannot pretend there isn’t a wider image problem, because, as Mitrovich rightly notes, it’s always the same tweet. Like when we are confronted with that question in real life, when we face it online, it is easy to try and explain away the problem or even deny that there is one, but we must try and work out why so many outsiders have this negative view of our genre.

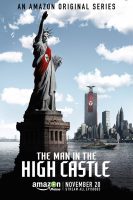

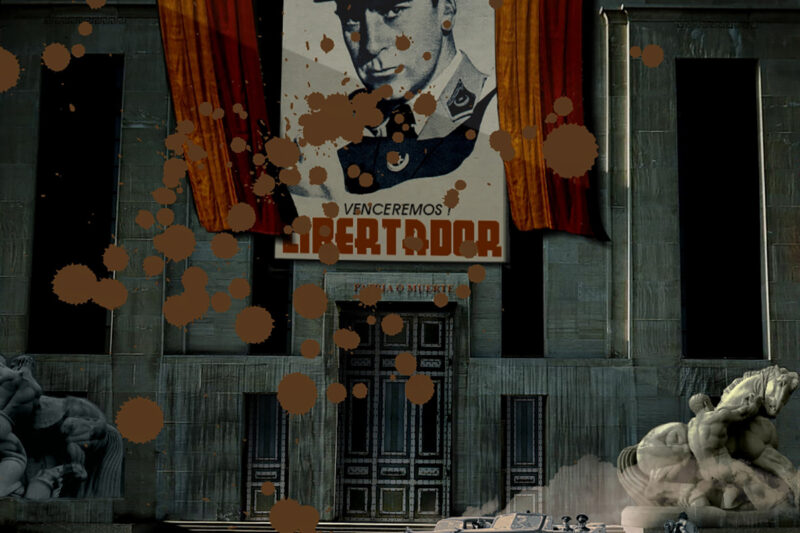

The answer is that not all fiction in a genre is equal, in terms of visibility and therefore influence. Numerically, of course, there may be more alternate histories that are not about swastikas over Whitehall or jackboots on Times Square, but what replies to this issue often fail to acknowledge, or rather do not want to acknowledge, is that it’s always the same tweet, because that’s how this genre is seen: as obsessed with the victory of Nazism and secessionist slave power. As much as I, personally, would like people to picture Ed Baldwin bouncing about on the Moon in his spacesuit when I bring up the genre, they do not see him. They see John Smith in his well-tailored SS dress uniform, draped in the swastika and stripes.

One of the most popular alternate history stories of recent memory was Amazon’s adaptation of The Man in the High Castle. Portraying the world of a supercharged Axis victory, in which the United States is split between a Nazi province on its East Coast and a Japanese protectorate on the West, the success of the show catapulted alternate history into mainstream respectability. Without it, we may very well not have shows such as For All Mankind, or adaptations of The Plot Against America, The Handmaid’s Tale and Bridgerton, nor the current feeding frenzy of interest in the genre.

However, High Castle is also a deeply irresponsible work, one which glorifies the conquering regimes. This is not a new critique, it must be said; Vox was full-throated in its condemnation of the show for becoming “plot-heavy Nazi kitsch,” as was Salon. Even director and producer Daniel Percival talked of his anxiety around attracting far-right fans in 2017 due to the iconography of the show, but justified the production as a way to reflect anxieties around the resurgence of fascism in our contemporary politics, particularly the Trump Administration of the latter teens.

Any good work of speculative fiction is reflective in such a way; Handmaid’s Tale was a mirror to Margaret Atwood’s anxiety of the Moral Majority and emergence of radical feminism with the hypothetical Gilead while Nineteen Eighty-Four reflected George Orwell’s anxieties of post-war England with the imagined Airstrip One. So it’s not terribly surprising that Percival would consider High Castle as an avenue to discuss his fears of Trumpist neofascism.

But there is a difference between an imagined country being used to discuss our anxieties, and using an historic regime to do the same. While we may shudder at the plausibility of Gilead and Airstrip One, as readers we accept their fictionality. They warn us that the respective totalitarian ideologies of the two regimes could succeed, future tense. But when we use real-life regimes to do this, an important thing happens. For High Castle to work, we must accept first that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan could have succeeded, past tense. Narratively, they must be empowered to victory. As writers we must revise history often along negationist lines to allow such a victory to occur. We proclaim that had things just gone another way, fascism could have triumphed as a legitimate alternative to democracy. And in allowing the Axis powers or Confederacy or whoever to have their victories, we debase ourselves morally, as we validate the real-world views of those who shoveled millions of human beings into ovens. And that’s the damn problem.

In a previous article, I discussed the ways in which Harry Turtledove’s foundational genre work, The Guns of the South, upheld the Lost Cause. High Castle, comparatively, upholds mythology around the Reich. In both show and books, we are presented Nazi Germany as a hyper-efficient regime empowered to the point of Venusian colonization. While there’s an obvious absurdity to the sheer expanse of Nazi Germany (and Imperial Japan), one which is directly commented upon with the in-text alternate history The Grasshopper Lies Heavy — which depicts a supercharged British Empire in a similar position (note that this is novel specific, in the show the novel Grasshopper is replaced with film reels showing in-real-life events) — nonetheless the Reich is shown within the flawed 60s lens of a frighteningly efficient regime that was capable and confident enough to conquer the Solar System, while Imperial Japan sits on the western shore of the United States, like a nightmare from the feverish depths of American wartime hysteria.

The depiction of the Japanese is, of course, Orientalist. The regime which in our world fought a genocidal race war in China worships the I-Ching, with inscrutable trade officials who practice wabi (far out of reach for our white points of view in the Pacific Coast, naturally) seeking cultural validation through the “authenticity” of Americana. But like Nazi Germany, Japan is presented to have been powerful enough to have conquered the Pacific United States. The idea of the Co-Prosperity Sphere, little more than Japan’s aim to dominate East Asia and the Pacific under a belief of racial superiority over the ethnic groups of the region, is ennobled in its victory, which shows us how such dramatically failed ethno-imperialism could have won.

Within the show, this sense of glorification is exacerbated to hitherto unseen scale by the depiction of Obergruppenführer John Smith, a character unique to the show and notably its most developed. Portrayed by the deeply charismatic Rufus Sewell, he is the protagonist of the political intrigue within the Nazi hierarchy, something largely unseen in the novel, rising and rising to Reichsführer of North America. The show takes deep care for us to understand Smith, his motivations and goals, to cheer him in his successes such as wiping out Führer Heinrich Himmler or outsmarting other collaborationists, such as J. Edgar Hoover, and to watch him rise, rise and rise. We cheer for him in his victories, we weep for him in his defeats, marvel with him as he traverses the quantum superposition and enters other worlds, and once we’re done, we’re happy for the catharsis of his suicide. When I think of Smith, I think of what David Chase said of his prestige TV antihero, Tony Soprano:

[The audience] had gleefully watched him rob, kill, pillage, lie and cheat. They had cheered him on. And then, all of a sudden, they wanted to see him punished for all that. They wanted “justice”. They wanted to see his brains splattered on the wall. I thought that was disgusting, frankly. The pathetic thing — to me — was how much they wanted his blood, after cheering him on for eight years.

Whereas The Sopranos cuts to black and forces us to look at ourselves in the mirrored screen of our TV sets and contemplate our hunger for violence, High Castle grants catharsis of perceived justice for the events it encouraged the audience to cheer on, an emotional and intellectual out for four years of tuning in each week to see what the American Adolf would do next. The audience is permitted to admire Smith on condition his downfall be spectacular and violent. But where does that leave us when we are permitted to admire a Nazi?

I should stress that I do not believe Philip K. Dick was himself sympathetic to these regimes, and neither are Percival and his writers on the show. But such questions of sympathies are irrelevant, because what do their versions of High Castle tell us? That Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan could have been triumphant over democracy and that the Reich would have built bullet trains and flown Concords and colonized our Solar System by early 1960s, etcetera. The average viewer departs from these interpretations, even when discounting the more fantastical elements, under the impression that there is “efficiency” in fascism, that the trains run on time. So is it any surprise that those with an ounce of critical thinking recognize this as glorification? Is it any surprise neo-Nazis revel in this world, or that a normal person may even walk away having a warped, even positive, view on the Reich and Imperial Japan due to the fiction of the show?

And when we look at other Nazi victory narratives that are at the forefront of alternate history’s mainstreaming, what do we see? A similar world of technological wonders in the Wolfenstein franchise with a catchy soundtrack of German-language cover songs and a London swaddled in swastikas in SS-GB to backdrop a detective thriller.

Just as Truffaut felt that every anti-war film ends up being pro-war, we must grapple with the possibility that works of Nazi victory invariably glorifies Nazism, even if the writers intention was otherwise. “To portray is to ennoble,” and in a time of reemergent fascism, it is our duty as the children of democracy to be wary of any such ennobling.

Is there an alternative? Of course. There are countless alternate history novels that are not Nazi victories. Apple TV’s For All Mankind has been renewed for a fourth season. The BBC moved away from dreck such as SS-GB and toward adaptations such as Mallory Blackman’s excellent Noughts + Crosses. And, at the risk of becoming a slightly self-aggrandizing advert for this very website, Sea Lion Press, mercifully, has very few true “Nazi victory” stories. A recent buyer’s guide listed only three, plus one Confederate victory.

The site prides itself on the diversity of its outlook, and Tom Black has been very conscious in curating such a collection which reflects the wider diversity in the genre. The move away from Nazi victory is the movement of the future, and as alternate history continues in the mainstream we will almost certainly see more and more examples that perhaps will redefine the popular perception. That will end the awkward question “oh so you mean like, what if the Nazis won?” Who knows, perhaps they’ll ask “oh you mean like, what if Harold Wilson was a spy?”

But that isn’t where we are right now. We cannot simply reassure ourselves that it is happening, and so insist that this tumor in our genre and the resulting image problems of it does not exist to those who continue to express frustration. We must actively work toward that point rather than just hope for it, if there is any hope for the genre’s future and its reputation.

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.

1 Comment

Add YoursThese works seem to ignore Americans being a contentious lot. One Star Trek TOS had a character named Bell who was concerned about a “dangerous anarchy.”

It may be that a directionless disintegration of the USA..considered really just a UK colony doing what Germany tried to do to Europe…shows how any thought to world domination falls apart…even China’s perhaps.