There are innumerable titles in the alternate-history genre that deal with a Great Britain occupied by the Nazis in the aftermath of their victory in the Second World War, from Len Deighton’s classic SS-GB to more recent works like C.J. Sansom’s lengthy and somewhat controversial Dominion (review here), not to mention many other titles published by indie authors.

There are so many, indeed, that it has become a distinctly tired trope within the genre, almost as stale as the overarching concept of the Third Reich Victorious scenario in general. Yet it cannot be denied that there is something to the concept of an occupied, fascist Britain that (perversely) appeals to me regardless of how uninspired it has become, and I’m always on the lookout for any alternate-history titles that offer an “alternate” take on the scenario and potentially rejuvenate it in the process.

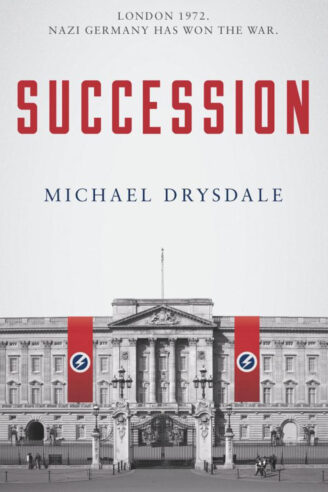

After a great deal of searching through the Kindle charts and on social media, I was finally able to come up with a potential candidate: Succession, by Michael Drysdale.

Unlike many other titles in the genre that I’ve noted above, however, Succession is not built on the concept of a direct Nazi occupation of the country; this is not a world in which a successful Operation Sea Lion led to Nazi jackboots marching through Whitehall. Instead, author Michael Drysdale offers us a far more nuanced and therefore interesting scenario, in which a failed Dunkirk evacuation and peace treaty leads to Churchill’s government fleeing to Canada with the nation’s gold reserves and Sir Oswald Mosley eventually ruling the country under the auspices of the British Union of Fascists in an authoritarian regime that brooks no dissension. But by the early 1970s, when Succession takes place, the BUF’s control over the country looks increasingly creaky, as does the European dominance of their Nazi allies in the face of American and Japanese technological progress and a constant, low-level state of civil war. It’s a deeply intriguing concept for a novel, especially creating a world in which the BUF have been dominant for thirty years, and I looked forward to jumping in and exploring Drysdale’s vision.

Upon starting the novel, it becomes clear that Drysdale certainly has a knack for rapidly drawing the reader into a narrative — in just a few short chapters we’re introduced to an Australian prospector who discovers a crashed aircraft and strong traces of radioactivity in its vicinity, and then a young woman who wakes up in London Victoria train station without any idea of her own identity or even where she is. Stumbling out into London, through her confused eyes we witness the tired, authoritarian world of a nation under BUF rule, in which Blackshirts hold daily marches through London, “subversives” who dare mock the aging leader, Mosley, are hunted by the police, and no one is certain of the loyalties of the person they’re speaking with.

Our main protagonist is Fleet Street journalist Andy Deegan, who balances a desire to report the actual, unvarnished truth with the needs of his family and the ever-present hand of the government censors who review and amend everything his paper publishes. A mysterious envelope is delivered to his office by unknown means and with no return sender; an envelope containing passport pictures of four men, three of which have been crossed out in red ink. A phone call from a frightened man, claiming to be the fourth photograph and in danger of being killed imminently, throws Andy onto the trail of the biggest scoop of his life — and one that could prove deadly both to himself and his family, and the BUF.

As Andy works his way toward revealing the identity of the murdered men, stonewalled by police and the BUF MP who owns his newspaper, a Salvation Army officer tries to help Mary uncover her identity. In the process, both of them find the apparatus of the fascist state increasingly arrayed against them in a desperate attempt to stop them uncovering a truth that could undermine the entire basis of the BUF’s thirty-year reign over the country.

Drysdale gives us an entirely convincing alternate Britain in the 1970s, in which the jeans, long hair and rock music of our period coexist uneasily with the fascist state and its increasingly brutal attempts to keep the population in check. Authoritarianism exists in a thousand forms, most of them simultaneously overt and yet strangely petty; for every Blackshirt march through the capital, police officers checking for those not cheering the procession or the forced haircuts of those deemed to have hair too long for them, Drysdale also gives us a world in which faded posters in the Post Office give crude “signs” of being Jewish or a homosexual and headmistresses enforce attendance at “patriotic” children’s camps. Drysdale has obviously done his research for Succession, and the various ways in which a moribund BUF tries to retain control obviously take inspiration from our timeline’s Nazi Germany, yet have also been deftly adapted for Britain.

Perhaps the part of the book that affected me the most was a discussion about the change in the Metropolitan Police: where once it was a matter of pride that someone being lost could consult a police officer for help, in this world you’re most likely to instead be arrested for wasting police time. Even the Samaritan Army — that most British and inoffensive of charities — are openly mocked and even assaulted by Blackshirts without any protection from the authorities. It’s a distinctly grim yet entirely believable scenario, and one that Drysdale implements perfectly.

Yet all is not well in the country for Mosley and his cabinet. There are signs of unrest around almost every corner, and it’s obvious that the regime cannot match the smartness and glamor of their Nazi compatriots, even if the latter do fall into fratricidal conflict every few months. Through the eyes of Andy Deegan, early on in the novel, we see his notes on the tired, aging Mosley and desperately ill king as they meet with the latest leader of the German Reich and parade through London; it takes an almost super-human effort to rewrite it as something positive, and throughout the novel it’s remarked upon that the king is rarely seen in public any more. Much of the brutality seen throughout the novel is increasingly tinged with desperation, and there are signs that the youngest generation are no longer content to simply bow to fascist oppression. Drysdale paints a vivid and persuasive picture of a second-rate fascist party struggling to control a nation deprived of its former world status and desperately trying to maintain its glamor compared to the victorious Third Reich, its pageantry a pale reflection of Nazi Germany and its rulers.

There are also some fascinating and thought-provoking worldbuilding elements that Drysdale sprinkles throughout the novel, engaging with elements of this particular alternate-history scenario that never seem to get much consideration in. While the notion of détente between Nazi Germany and the United States is quite a common trope — though the idea of Richard Nixon traveling to Berlin and declaring “I am a Berliner” is a delightful image — Drysdale also develops the notion of “Free” Britain and the Churchill government-in-exile in a way I haven’t seen before.

While it’s incredibly powerful in the early 1940s, bolstered by the bulk of the Royal Navy, the War in the Pacific and then decades of fruitless attempts to gather support to invade the UK leaves it a pale shadow of itself, eventually reduced to just a few retired admirals in Bermuda. Drysdale cleverly makes use of HMS Belfast — that stalwart of the British museum scene — as a metaphor for the fall of Free Britain. While initially loyal to Mosley, it mutinies in 1943 and subsequently fights alongside Free British forces in the Far East. But after the conflict it’s eventually sold to Canada as Free Britain cannot afford to maintain it and its aging crew; renamed Newfoundland, it becomes a “goodwill vessel” that visits the UK to demonstrate the slow thaw in attitudes between fascist Britain and its former dominions.

All of this excellent worldbuilding is linked to a fast-paced and engaging plot, one that moves smoothly from Andy Deegan investigating a series of murders to picking up clues to gradually uncovering evidence as to Mary’s true identity — and a secret power struggle at the very top of the BUF. It’s a narrative that unrolls smoothly throughout, each chapter streamlined and absent of the padding that often dogs titles in this genre, escalating all the way to an explosive conclusion that completely changes the nature of the regime and its control over the nation.

I could, perhaps, have done with a few more chapters at the very end of the novel to expand on some of the points raised by the very end of the plot, and to explore some of the key results of the changes that take place. But this is a distinctly minor point to bring up, and does nothing to change the fact that Succession is a fantastic novel by Michael Drysdale — the kind of title that the alternate-history genre desperately needs to keep stale scenarios like this fresh and engaging to its readers.

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.