In 1928, Karl Mannheim devised a completely new concept of generation. Not just the natural regeneration of a population, Mannheim theorized that a generation shares a common dramatic fact that influences and forms every concept, every belief, every behavior of that particular group of people that lives in the same time, place and cultural environment.

There’s no doubt that World War I formed the generation of Weimar. The young people who fought in the trenches thought their elders, their parents, their fathers and mothers, could not understand what that meant. The experience of war was so intense and life-changing that those young men truly believed nobody but others like them could understand. They did know that their fathers’ world was gone forever and its values with it, and so they thought their elders could teach them nothing useful and they had to create their own new world, with their own new values.

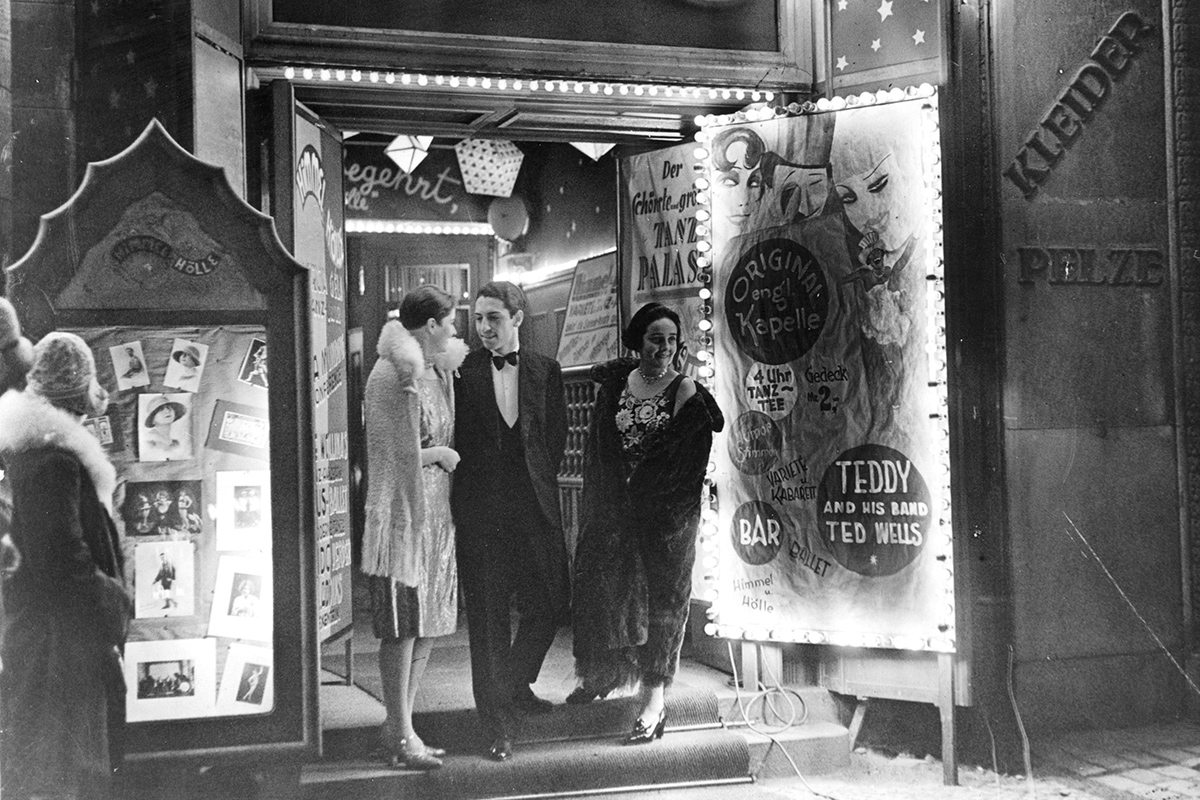

Besides, they were not scared of experimenting. Any novelty was worth trying.

For women, the war meant emancipation and independence. For young men, the war meant a new ideal, a new way of life and new expectations.

The patriotic soldier became the model to strive for. Strong, brave, physically apt and handsome, noble in spirit, he would give his life gladly for his nation and his people. It seems a very positive ideal, but it often turned on its head. Because this was the virile ideals, the contrary of it — or what it was perceived as contrary — became despicable: ugliness, immorality, cowardice, weakness. These characteristics were often attached to “the Other”, the outcast, like Jews, homosexuals, but also intellectuals and even former soldiers who couldn’t cope with the experience of the war or were permanently disabled.

The 1920s saw the rise of the new woman, but also the strong reaffirmation of masculinity.

Front Generation

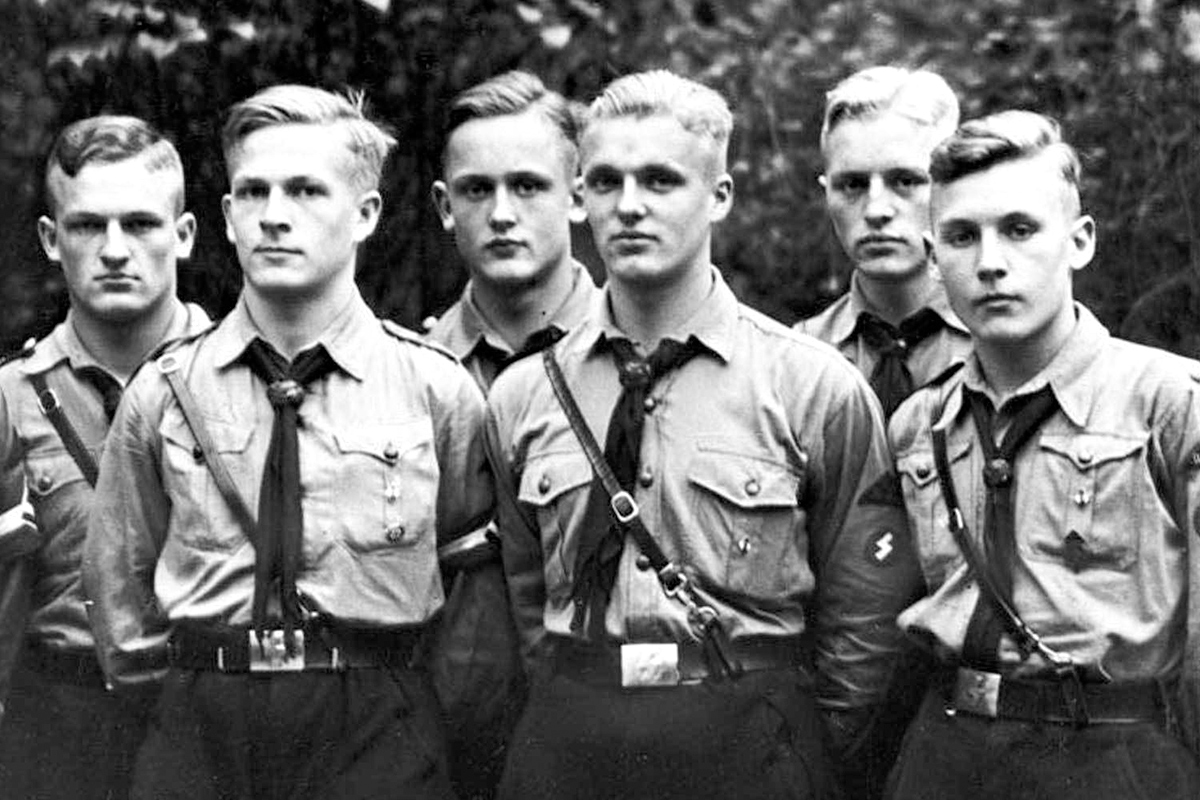

The Frontgeneration started to come together right after the war, in the messy world of the Revolution and then the Weimar Republic. At first, they gathered in organizations that were almost secret societies, to share the experience that non-veterans could hardly understand. These youths sought to create a new world, different from the one which died in World War I. They utterly refused the passivity of their elders and wanted to act. They refused to look back at the past and tradition and stubbornly looked ahead. They felt that they had fought a war that had taken all certainties from them, but had also given them the skills to create a new reality that rested on the values they had learned in the trenches: bravery, courage, camaraderie.

These values of the trenches soon merged with the new nationalism, which brought these “secret societies” to light. Paramilitary forces of every kind were born, entities that sought to recreate a romanticized version of the experience, the brotherhood of the trenches. The virile affirmation of national pride often turned into violence, since for these youth that had fought in the trenches, violence was a part of life that they were ready to use again.

The Weimar Republic was a heavily militarized society, where the elders came from a Prussian cultural upbringing and the young came for World War I. Seeing a future of peace was probably hard for everyone.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 29, 2018.