The late 1960s were a time of upheaval in the transatlantic relationship. Charles de Gaulle had withdrawn from NATO’s integrated military structure and was seeking equidistance for France between the Soviet Union and the United States. Willy Brandt, West Germany’s first center-left chancellor, was pursuing Ostpolitik. Britain had finally been admitted to the European Economic Community, which — in Washington — raised fears of a united Europe challenging American primacy in the West.

Mired and later defeated in Vietnam, America’s prestige was at a postwar low. The oil-producing countries of the Middle East were starting to use their economic power for political gain. Japan was emerging as a global powerhouse in the East. The Atlantic alliance looked divided and exhausted.

Opening

The good news was that Moscow felt better. Having crushed the 1968 Prague Spring, the Soviets felt secure in their control of Eastern Europe. They had also achieved nuclear parity with the West and were willing to talk about normalizing East-West relations.

The rest of the Eastern Bloc felt less comfortable. The communist economies were stagnating. Eastern Europeans knew that Westerners were far better off. There were calls for increased openness to bring in Western investment and trade.

Daniel Thomas writes in The Helsinki Effect: International Norms, Human Rights and the Demise of Communism (2001),

The fact that such access could never be achieved without a lessening of political confrontation with the West contributed to the growing pro-détente lobby within the Warsaw Pact.

There was an opening to reduce Cold War tensions.

This caused concern in Washington. Hastings Ismay, NATO’s first secretary-general, had famously said the pact existed “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in and the Germans down.” If Eastern and Western Europe drew closer, and Brandt’s Ostpolitik succeeded, it could undermine NATO’s three goals.

Compatible

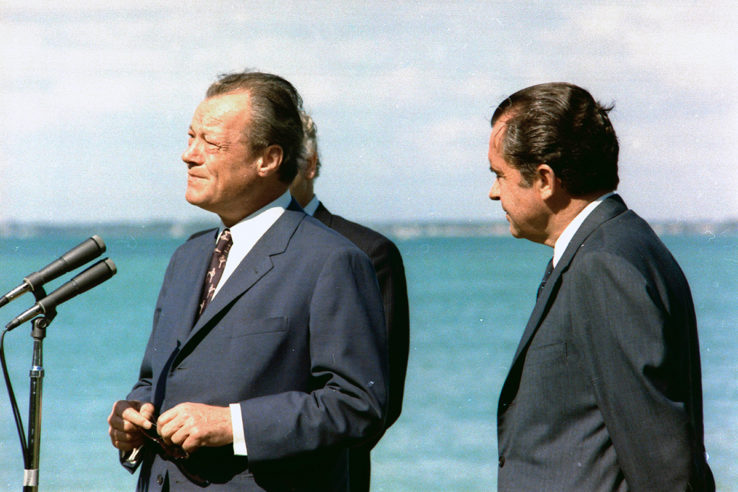

Brandt had broken with the foreign-policy consensus of the early Bonn Republic, which, under Christian Democratic leadership, was unambiguously Atlanticist. The Social Democrat believed in normal relations with East Germany, which West Germany had until then refused to recognize as an independent state. The Soviets reciprocated and negotiations about formalizing the borders in Eastern Europe followed.

Britain’s Labour government was sympathetic. France and the United States were skeptical. “Their concern that German Ostpolitik could acquire a dynamic of its own, and therefore needed harnessing, limited Bonn’s room for maneuvering,” writes Helga Haftendorn in “German Ostpolitik in a Multilateral Setting,” published in The Strategic Triangle: France, Germany and the United States in the Shaping of the New Europe (2006).

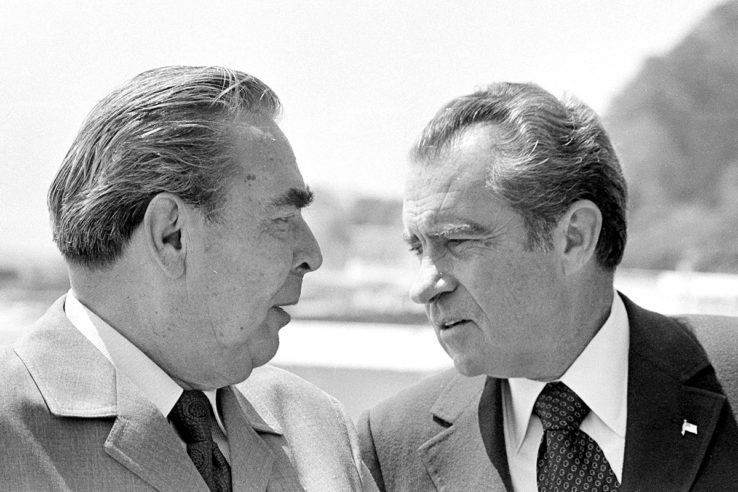

It eventually dawned on the Americans that Ostpolitik was in fact compatible with détente. The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty Richard Nixon signed with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in 1972 could not have happened without the Moscow and Warsaw Treaties of 1970, in which Bonn accepted the de facto borders in Eastern Europe. (But not the German right. See Niemals Oder-Neisse: The Border Germany Refused to Accept for 45 Years.)

In common

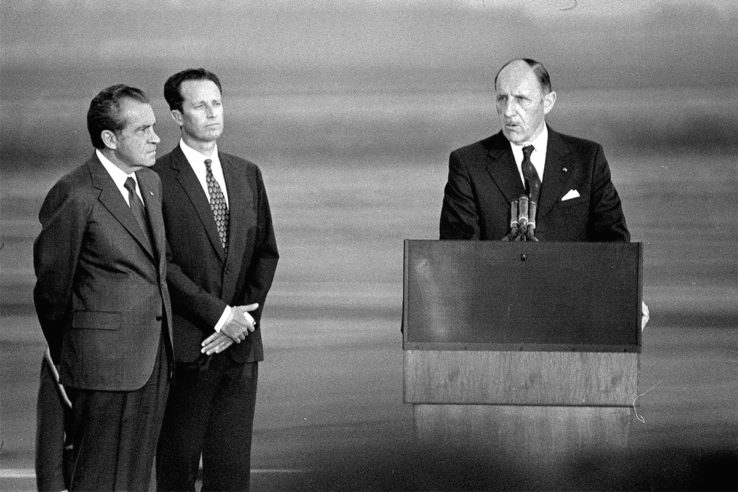

This recognition didn’t resolve all tensions in the Atlantic camp. When Nixon abandoned the gold standard in 1971, and when American weapons stored in West Germany were shipped to Israel in 1973 during the Yom Kippur War, Europeans were not consulted or even informed beforehand.

What kept the alliance going? For one thing, the Soviet threat. Memories of the Prague crackdown were fresh. Whatever qualms the Europeans had about American militarism, when it looked like Congress might reduce America’s troop presence in Europe after the war in Vietnam, the allies lobbied against it.

America’s sense of malaise going into the 1970s also reinforced the psychological need for allies and friends. America and Europe still had far more in common with each other than with the communist world.