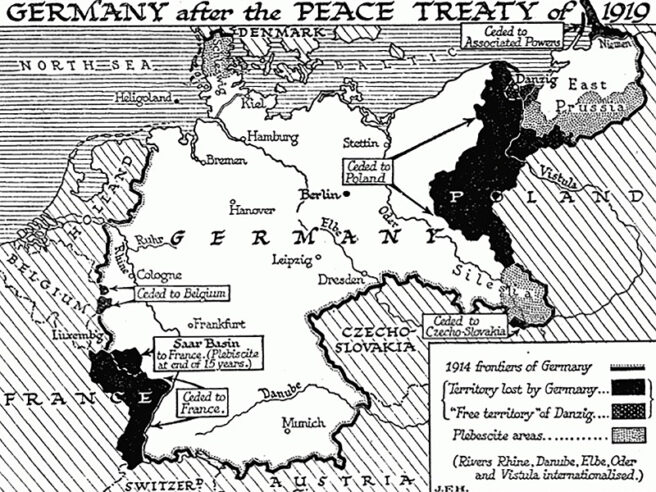

Germany’s World War I-era government collapsed on November 10, 1918. The armistice ending World War I quickly followed. From November 1918 through May 1919, Germany’s new civilian government fought a series of small-scale civil wars against German Communists.

Meanwhile, the victorious Allies were hammering out the terms of German surrender. They were harsh. The Allies presented those terms to German negotiators on April 29, 1919. The terms were published in Berlin on May 7, 1919. The Germans were furious, but by that time they didn’t feel that they had much choice but to sign. They signed the treaty a few hours before the deadline on June 24, 1919.

As Allied terms for Germany’s eastern borders became more apparent, some circles in Germany seriously considered going back to war, at least in the east. Cooler heads prevailed, and Germany’s border with Poland was temporarily settled through a mixture of plebiscites in some areas and small-scale wars between unofficial forces supported by the two countries in others. Germany actually didn’t do too badly in the border disputes. Some mixed areas went to Poland, but others went to Germany. Interwar Germany had quite a few Poles.

What might have happened if Germany had gone back to war?

Border war

In early March 1919, word of the plans for the German-Polish border leak out. Those early plans were much more favorable to the Poles than the border that was eventually established. They would have left three million Germans inside Polish borders, and would have given Poland a large chunk of Prussia.

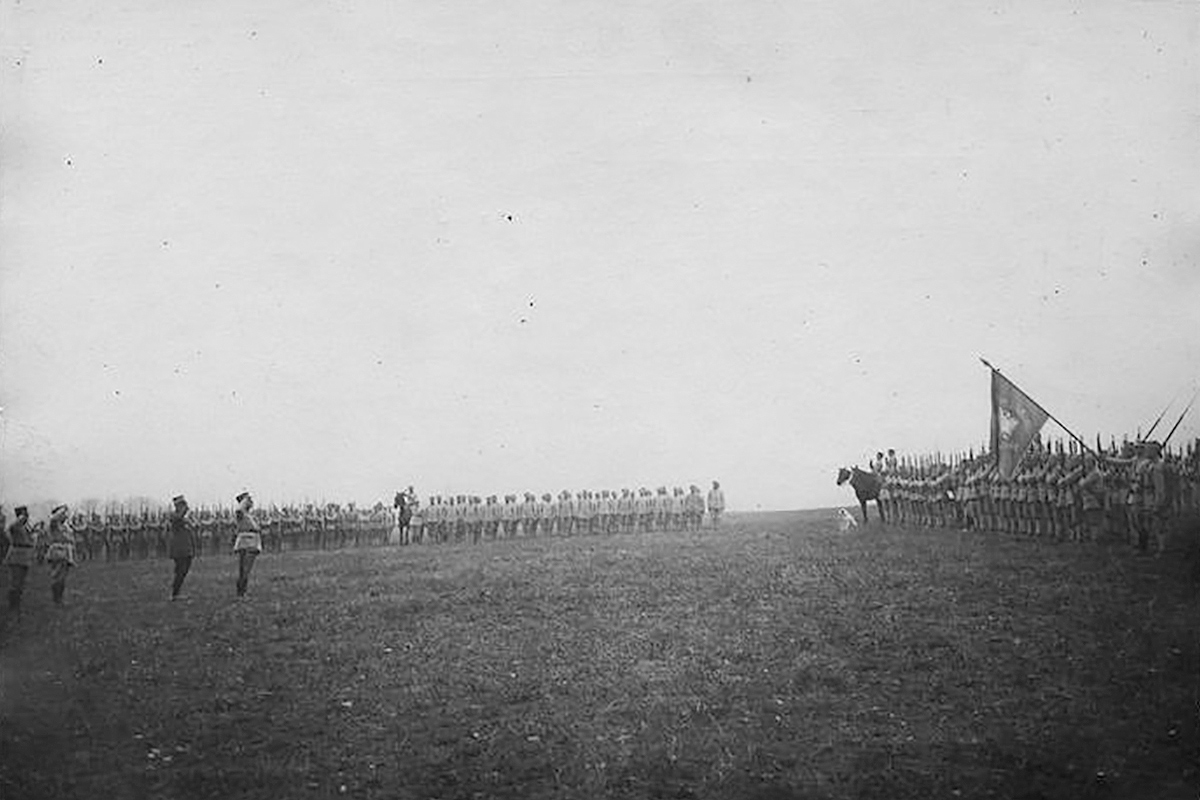

The Allies deny that any border has been agreed upon. That is true, but it is not believed in Germany. Germans in the disputed regions have already formed militias to fight the Poles and the Communists, but the fighting with the Poles has died down to some extent. German nationalists now begin mobilizing for an all-out war. The German army also begins making contingency plans for resuming the fighting if the peace plan is not acceptable. German militias in border areas with Poland become very well armed. They win some big victories in the renewed fighting and it becomes obvious that the Polish army itself is in trouble.

The most effective Polish army in existence in 1919 is something called Haller’s Army (or Blue Army), after General Józef Haller. It is a French-trained and -equipped group of somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 men who were being groomed for a role on the Western Front at the end of World War I. In March 1919, Haller’s Army is still in France. It’s needed urgently in Poland. In our history, Germany reluctantly allowed Haller’s Army to be shipped across Germany over a period of time — probably in late March or early April 1919. In this scenario, the Germans don’t actually refuse to let it cross, but they procrastinate throughout April. The Poles desperately need that army. They are fighting border wars with German nationalists in the west and Ukrainian nationalists in Galicia in the east. German soldiers returning from the Eastern Front are encouraged by German nationalists to turn over their weapons to the Ukrainians. Some even stay as mercenaries or advisors.

The Allies are reluctant to start the war up again. They take some precautionary steps, but otherwise wait to see if the German government will sign the peace treaty. Parts of Haller’s Army gradually filter over to Poland in roundabout ways through May and June, but the Poles take it on the chin both in the German border areas and in Galicia. Lviv falls to the Ukrainian nationalists in early May. Along the German-Polish border, the German militias gradually advance, constrained more by fear of Allied intervention than by Polish opposition. Haller’s men gradually change that as the deadline for the peace treaty approaches. The Allied attitude toward the Germans hardens as it becomes obvious that the German militias are being used by the German government to impose their vision of peace in the east. As a result, the Germans fare worse in the peace treaty than they did in our timeline. The Allies repeatedly demand that Germany disband its militias. Germany claims that it does not control them.

The Germans still have forces on the other side of Poland, along the old Eastern Front with Russia. The Allies have encouraged those forces to remain as a screen against the Bolsheviks. As tensions rise between the Poles and the Germans, supplies to those forces through Poland becomes an issue. Germany tries to keep that eastern army in existence. That’s difficult because the men are tired of war and just want to come home. Poland frantically tries to build a modern army while the new German regime tries to consolidate power, partly by appealing to German nationalism and anti-Polish feelings.

Dangerous game

The Germans work frantically to line up allies. They try to line up discontented elements in what used to be Austria-Hungary. They try to work out a tacit understanding with the Bolsheviks to cooperate with the Germans against the Allies. In our history, a Bolshevik regime took power in Hungary from March to July of 1919 but was defeated by the Czechs and Romanians. In this scenario, the Germans wouldn’t be eager to help the Bolsheviks given their own internal situation, but they might use the situation to distract the Allies.

The German government knows that Germany can’t win a renewed war. They also know that the Allies are not at all eager to restart the fighting either. They play a dangerous game, skating to the edge of renewed war to gain concessions. The deadline for the Germans to sign the treaty comes and goes. The Germans say that they don’t want a renewed war, but that no German government can sign that peace treaty. They also play the Bolshevik card, saying that trying to impose the treaty will lead to a Bolshevik takeover in Germany.

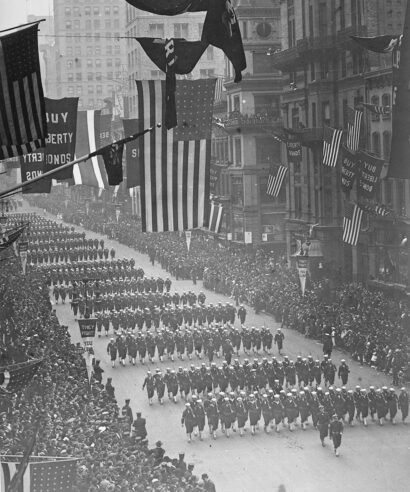

The situation gets out of control. Haller’s army is now mostly in place. The French have sent large amounts of equipment to Poland, though it takes a while due to the roundabout way it has to get there. Large numbers of French officers are training the new Polish army. The tide turns in the war between the German militias and the Poles. The Germans funnel more arms and men to the militias and to the Ukrainians. The Allies are somewhat split. The French want to make sure the Germans are not in a position to become a power in Europe again. The English are reluctant to go to war again to put more Germans in Poland. The Italians aren’t pleased with their booty from the peace treaty. Any Italian contribution would be token. The Americans just want to get their people home again. But none of them are willing to let Germany get away with defying them. The Allies declare that a state of war exists and issue an ultimatum to expire in 48 hours.

Pseudo-World War II

The German government makes the decision to sign but is quickly overthrown by nationalist army officers. In the chaos, the Bolsheviks make another bid for power. As the fighting inside Germany goes on, the time limit on the ultimatum expires. The Allies start their advance. The German Bolsheviks are put down with a great deal of ruthlessness, and the new regime tries to gather the shattered country for war. Germany is still under blockade and they desperately need food. The Germans decide to try to hold the line in the west while destroying Poland or forcing it to capitulate in the east. That would give Germany renewed access to the Ukraine’s farmlands and give it a fighting chance.

In Russia, the fighting complicates an already strange multisided struggle. The Allies want to help a White (anti-Bolshevik) Russian regime to power. Then they could funnel aid to Poland through Russia. The Russian Bolsheviks are trying to help their German comrades overthrow the German government, but the Russian Bolsheviks are tacitly allied with that German government against the White Russians and the Allies. The White Russians aren’t thrilled by the existence of an independent Poland, but are willing to tolerate it for the time being in order to get Allied aid. Ukrainian, Lithuanian and Belorussian nationalists are willing take help from anyone who will give it to them, but they are smart enough to realize that the Germans are probably going to lose, so any alliance with the Germans is unspoken. German “mercenaries” train their armies in exchange for food. Unfortunately, the nationalist governments are weak enough that they can’t really ensure that food. They are also wary of the Germans, because the Germans helped overthrow an earlier Ukrainian government in favor of a puppet government.

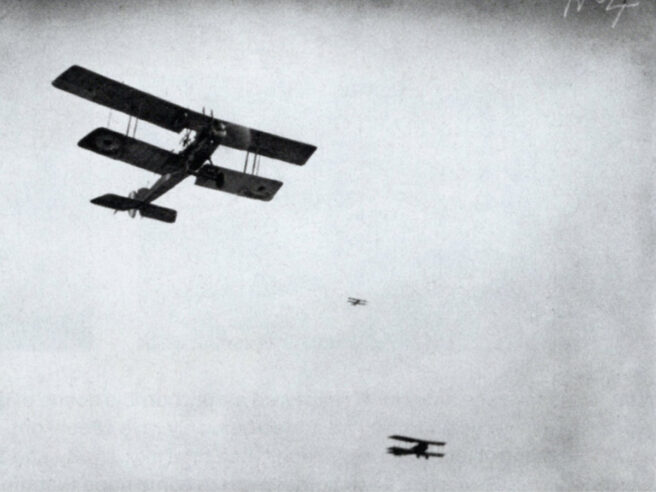

This strange pseudo-World War II goes on from about June 27, 1919 to late November 1919. The Germans initially win big in Poland while giving ground reluctantly in the west. The Allies have such a superiority in tanks and aircraft and manpower by mid-1919 that the German retreat in the west starts to become a collapse. The German offensive into Poland takes Warsaw, but the Poles fight on and the Germans have to pull most of their forces out to fight in the west to avoid defeat.

Defeat comes anyway. The Allies have literally thousands of tanks, and use them in masses. They have control of the air. The only reason the war doesn’t end sooner is that the Allies can’t find a German government willing to surrender to them, so they have to take the entire country, fighting pockets of diehard nationalists and Bolsheviks. Although troops from the west and Poland link up in November 1919, pockets of fighting go on into 1920. Diehard German troops continue fighting on various sides of the Russian Civil War for years afterward. (Which implies that the Russian Civil War lasts longer in this scenario — I’ll get to that.)

How realistic is all of this?

The Germans would be stupid to do this, but there have been plenty of times when a determined minority have forced a government into an impossible situation. If the Germans from the areas that were to be lost to Poland had time to organize, they could have made it impossible for Germany to sign the Versailles Treaty. I can’t see the Allies letting the Germans get away with not signing, so I think it’s very possible that war could have come again in 1919, in spite of the war-weariness in every country.

Short-term consequences

In Russia: With a war going on with Germany, Allied aid to the White Russians in 1919 would be more determined. I suspect that the Whites would be able to physically occupy Moscow and possibly Petersburg. That wouldn’t end the Civil War. The Bolsheviks would probably regroup somewhere in Russia, just like the Chinese Communists did after they lost to Chiang Kai-shek in the first round of the Chinese Civil War. There would be a long period of chaos in Russia as the White Russians attempted to establish effective control. They would be resisted by the remaining Bolsheviks and by a bewildering array of local forces representing peasant and worker factions. I could see civil wars continuing into the mid-1920s.

In Germany: That’s a tough one. If the German Communists were smart, they would try to wrap themselves in the mantle of opposition to foreign military presence. German nationalists would blame the Communists for a “stab in the back”. Separatist forces would be strong in some parts of Germany. (They were in our timeline immediately after World War I.) France and Poland would encourage those separatists. The Allies would give Poland its maximum demands against Germany. Any disputed areas would go to Poland, including about a third of the part of East Prussia cut off from Germany by the Polish corridor. The rest of East Prussia would become a nominally independent state under Poland’s watchful eye. Initially, the Allies would try to extract huge war reparations from Germany. When that doesn’t work, they would start dismantling industrial machinery and carting it off. Eventually they would realize that wasn’t going to work either. Germany would have to be integrated back into the world system in some way. I suspect that would happen in the mid-1920s.

In the Allied countries: The Allies would end up with a big emotional commitment to Poland’s borders with Germany. After all, that’s what round two of World War I was all about. They would also end up with more experience at mobile warfare and more appreciation of the value of tanks. Unfortunately, they would also end up with more obsolete Renault FT tanks. That haunted the French army through the beginning of World War II in our timeline. There would be even more fear of Germany throughout Europe. I think the Americans would still go isolationist. England and France would probably be forced to remain close for a while longer, but they would still become rivals to some extent in the 1920s. Italy would still be dissatisfied by the peace, and it would still probably give rise to Benito Mussolini or someone like him. As revolutionaries in Russia, Lenin and company would have less influence in the rest of the world than they did as the leader of a major power. That would have major impacts on European politics. I have no idea how that would play out.

In Central and Eastern Europe: Poland would expand at the expense of Germany, but it would also have less territory in the east. Given this scenario, I suspect that Poland would not be able to expand very much into disputed territory on the east. It would probably end up with about the eastern borders it has now. There would probably be an independent Ukrainian state, though it would not control the majority of Ukrainian territory. It would be somewhat larger than the Ukrainian-speaking part of Galicia. Its existence would be precarious, with both the Poles and the Russians claiming parts of it, but both of them would be otherwise occupied so it might survive. I doubt that much else would change. The winners among the little countries of Central and Eastern Europe would still be too greedy for their own good. The losers would still want revenge.

Long-term consequences

Would there be a Great Depression? Probably. World War I did too much damage to the world economic system. Those chickens had to come to roost somehow and somewhere.

Would there be a real World War II? Eventually. The Germans wouldn’t find it quite as easy to rearm in this situation. The Poles would know that German rearmament would eventually mean the destruction of their country. They might intervene quickly and unilaterally. At the same time, I can’t see the likes of France, England and Poland keeping the Germans down in the long term.

Two nightmare scenarios:

- World War II is delayed long enough that when it does come it ends with two or more combatants using nukes.

- World War II comes earlier, before tanks and trucks are reliable enough to pull off quick advances. Europe could not have survived another World War I-style war of attrition and remained civilized.

This story was originally published on Dale’s website in January 1998.