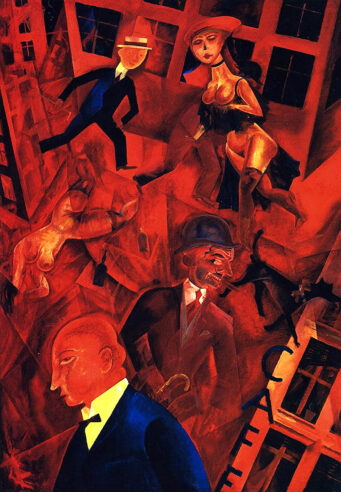

The Weimar Republic is often considered one of the most remarkably energetic periods in the artistic history of humanity, a roaring surge of modernism in all fields of arts, where experimentation was the norm. For a glorious, if all too short, period over the “Golden 1920s” and the first part of the 1930s, while Germany went through one of the most troubling political and economic times in her history, Berlin was one of the most exciting places in Europe where an artist could be. Possibly in the world.

The Weimar Constitution guaranteed to everyone the right to “express his opinion freely in words, writing, print, pictures and in any other manner,” and artists, both Germans and foreign, took this opportunity to its fullest. No aspect of the liberal life of the republic was left out. Arts often depicted the liberation of women, the free expression of homosexuals as well as the realities of post-war that people would have probably preferred not to see.

One of the centers of this new concept of arts was the Bauhaus in Weimar, an ensemble of artists, but also an educational institution, which offered tuition in many modern arts and encouraged the use of new materials and new industrial processes. It was also a kind of utopian social commune, an experiment just like the republic itself was.

Art was often a political assertion in the Weimar Republic. This is why the reaction to arts was likewise political. The right-wing parties and völkisch sensibilities saw this freedom of expression as a true subversion. Art didn’t shy away from any forms of corruption, both personal and political, of sexual display and of mutilation. It depicted and scrutinized the uncomfortable realities of postwar life. It was accused to try and destroy everything that still was genuinely and traditionally German. Acting like a deforming mirror, modernistic art of all forms was considered to not a depiction of reality, but an apology of everything decadent or corrupted.

Since in the eye of the right everything subversive was automatically Bolshevik, this artistic attitude was dabbed Kulturbolschewismus (Cultural Bolshevism). It would have been called “degenerate art” only a few years later.

Neue Sachlichkeit

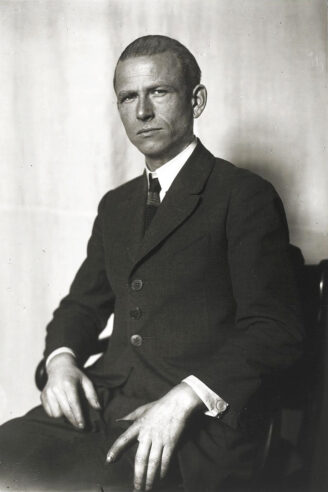

In November 1918, Expressionist painters Max Pechstein and César Klein formed an artistic group whose purpose was to go beyond Expressionism. The November Group “were confident that merely by rejecting the sentimentality of prewar German Expressionism, and substituting a more realistic, sober view of the life around them, they could not only bring about a new society but usher in a ‘new man’.”

This was the beginning of what was known afterwards as Neue Sachlichkeit, which is often translated into New Objectivity, but could also be understood as New Realism.

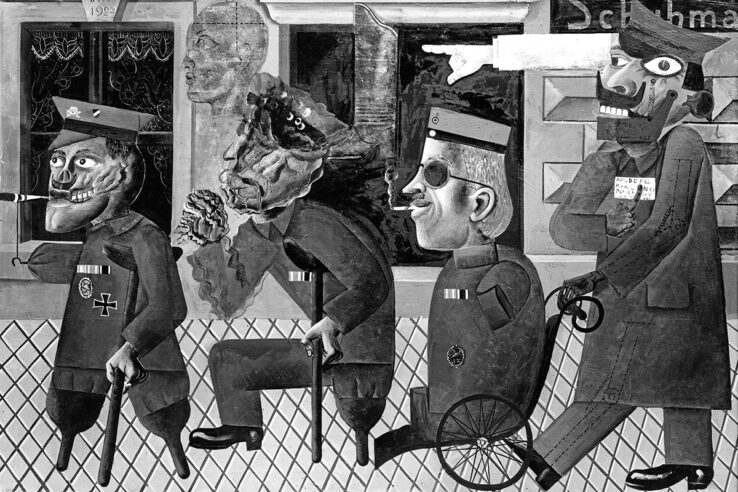

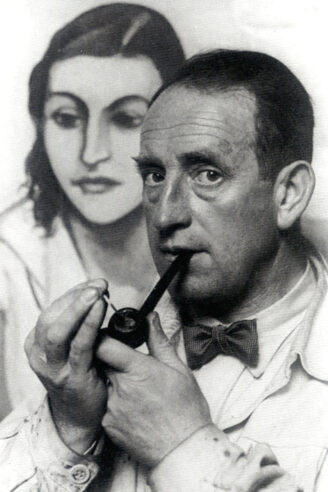

The artist who joined this movement didn’t share a style but rather an ideal, and most of them had been in the war. Otto Dix had been a machine-gunner during World War I and George Grosz had fought in the trenches too. These artists saw with great clarity the consequences of the war, which were never good in their eyes. If the republic had brought freedom — which was what allowed them to express their opinion — it had also brought corruption, illness, deformation, both physical and intellectual. They sought to express this not by turning inside themselves and their own experience, but by depicting it as it truly was and everyone could see. The subjects of their art were the maimed veterans, the disfigured bodies and faces, the underworld with its prostitutes and gangsters, the corruption of politicians and rich industrialists.

Their realism became sometimes so extreme that it almost turned grotesque and slid into surrealism, which gave one more key of interpretation to the reality they knew.

The work of these artists was considered by the right degenerate art without exception.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 12, 2018.