Germany had been a Kaiserreich — an Empire — for over fifty years. In this time, many rights had been extended to a larger population. It could be said that democracy had advanced, although the government responded to the Kaiser rather than the Reichstag, the parliament.

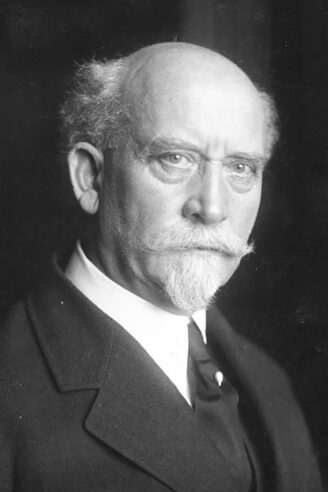

In the dramatic times at the end of World War I, in the hope to create a change that would please the Allies, Kaiser Wilhelm gave the chancellorship to Crown Prince Maximilian von Baden, who had always been of liberal feelings. After trying unsuccessfully to turn the Empire into a parliamentary monarchy, Von Baden opened the Reichstag to the Social Democratic Party (SPD). He immediately started to negotiate with the United States a possible peace, but didn’t find the favor he was hoping for.

The sense that the war was ending, and not favorably, arose in the country. The rebellion spread all over Germany, picked up by the bigger personalities of the Communist Party.

Hoping this would calm things down, removing the main connection between Germany and the war, Max von Baden resigned his chancellorship in the hands of the SPD leader, Friedrich Ebert, and urged Wilhelm II to abdicate.

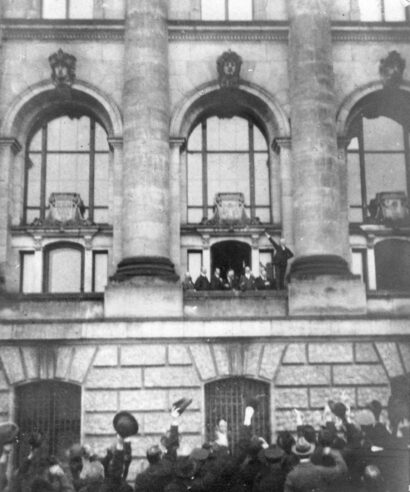

This happened on November 9, 1918. Trying to prevent the Communists from proclaiming a socialist republic which would end up under the influence of Russia, one of Ebert’s fellow partymen, Philipp Scheidemann, proclaimed the Republic of Germany without any consultation. Only afterwards, in the town of Weimar in Thuringia, away from the mess in Berlin, the democratic Reichstag wrote its own constitution.

For the short time it lived, the Weimar Republic was indeed a beacon of democracy. It allowed large parts of the population to take part in the political life, a few for the first time ever. It was, in fact, the first German regime which granted the right to vote to women and full citizenship to Jews.

Engulfed, like all the Western world, in the dramatic social changes of the beginning of the twentieth century, the republic embraced it and made it its own.

Freedom of expression was widely recognized, giving rise to an extraordinary diversity of papers, magazines and publishing houses. Philosophy and literature flourished. Many artistic movements — Expressionism, Dadaism, the Neue Sachlichkeit, to mention only a few — were at home in Germany and found there their highest form of expression. New ways of creating design, using new materials and new industrial processes arose (Bauhaus).

In a society that had been extremely strict under the Empire and had known the rebellion after the war, sensuality and sexual impulses became an ever more common way of expression, especially when meeting the sexual liberation common to all the Western world. It was in Germany that the first institute for the study of sexuality was founded by Dr Magnus Hirschfeld, who was an activist in the movement for the rights of homosexuals. The Reichstag even discussed the practice of abortion and contraception, which should have been available freely.

It has often been speculated that the republic, born in messy times and always moving on rocky ground, never really had a chance for success. Socialists, social democrats and Communists, who should have been the republic’s paladins, never supported it as much as they should (or could) have, disappointed as they were with what they considered only small improvements. They expected a lot more from democracy.

Besides, the republic had many enemies who gladly pointed out its weaknesses.

One weakness was the political divisiveness. The republic’s parliamentary situation was always shaky. There was never a majority who could safely govern, because even inside the same political areas there was no agreement. Both the left and the right were divided into many smaller groups and entities that seldom came to an agreement. This created mistrust in the population, who generally believed politicians were corrupt and selfish.

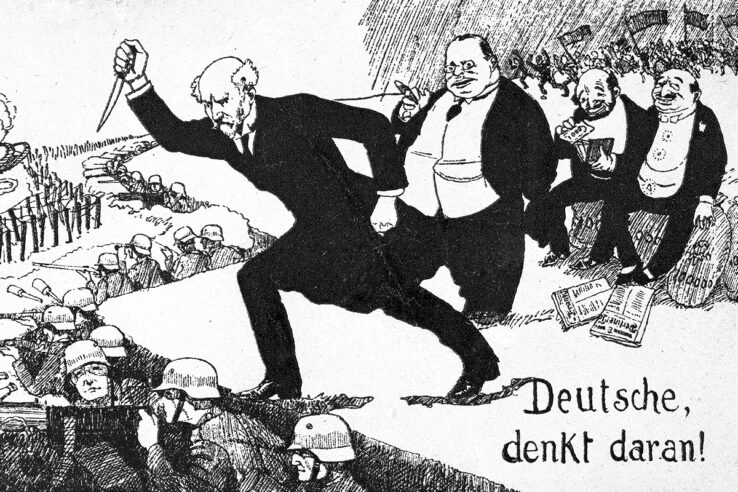

This mistrust was good soil for any kind of conspiracy theory. The most followed was the Dolchstoßlegende — the stab in the back. It theorized that Germany was actually winning the war (Germans had firmly believed it to the end. Besides, they were led to believe so) and the November 1918 surrender was engineered by socialists, liberals and Jews in Germany’s civilian government. It wasn’t at all the result of military defeat or exhaustion. The fact that the new bourgeois government signed the hated Treaty of Versailles, and that the military generals didn’t even participate in the meeting, made this belief even stronger. Many right-wing parties used this theory for gaining momentum, and none better than Adolf Hitler’s NSDAP.

Weakness was the inclination of the republic to come to terms and compromise with forces that were their natural opponents. For example, in the revolutionary times, the government had to compromise with the army in order to bring back law and order, in spite of the Reichswehr being one of its strongest enemies.

Today, though, historians tend to agree that the SPD had very little choice. The compromises they accepted were not out of weakness or indecision. If they hadn’t accepted them, the republic’s life would probably have been even shorter.

But maybe the ultimate weakness of the republic was the exceptional power the constitution gave to the president. In times of crisis, he could jump the Reichstag and take his own decisions, as the old emperor would.

This constitutional provision is widely considered one of the main causes that would eventually allow the Third Rich to rise to power.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 4, 2018.