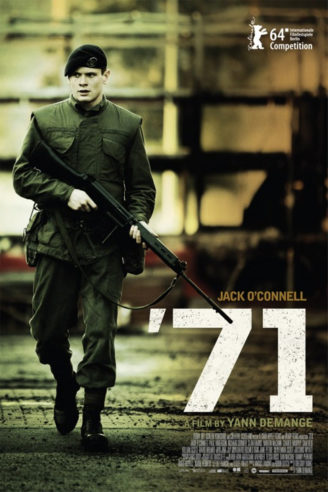

If I had to describe ’71 in a single sentence, I’d say “Black Hawk Down in Northern Ireland”. It has the same inciting incident: a soldier is cut off from his unit in a foreign land and has to survive surrounded by enemies. But that is where the similarities end.

For one, it is made clear to our protagonist (Jack O’Connell), after he goes through boot camp, that he is not leaving the country. This soldier is British, and he is being sent to Belfast, a city engaged in low-scale civil war between Catholics and Protestants. In an attempt to placate a riot, he is lost in the chaos and has to navigate a complex world of sectarian tensions and conflicting paramilitaries.

Almost immediately, the movie slams you with the reality of the saying, as Orwell did, “Those who ‘abjure’ violence can do so only because others are committing violence on their behalf.” One generally thinks of the United Kingdom after World War II as a peaceful country; indeed, one book I’ve read about the subject is entitled The People’s Peace, by Kenneth O. Morgan (1990). But even on that windswept island, there was war: pubs in Guildford and Birmingham were bombed by the IRA, to give but two examples.

Across a sea that at its shortest is merely twelve miles, there was a very different story. The Troubles were a brutal ethnic war, one that fortunately did not devolve into what was seen in Rwanda or Bosnia, but with no less hatred and division. The officer who briefs our protagonist stresses that “You are not leaving this country.” Yet what he sees in Belfast is very different from the pristine first-world image of postwar Great Britain. It is a divided city, not unlike Berlin, on the frontline in its own war. It works very well as a way of showing that war, chaos and violence are never far away.

The film works magisterially as a meditation on the pointless cruelty of sectarian conflict. Bars are bombed and children are killed in a seemingly never-ending slog between the warring factions. There is a constant fear among civilians that one paramilitary or another will end up destroying whatever prosperity they have eked out. It isn’t romantic or heroic in the slightest; it’s just deeply sad.

’71 joins the exalted ranks of anti-war films, and succeeds in being one without falling victim to French New Wave director François Truffaut’s objections to such stories: that even anti-war films need to make war exciting in order to retain their audience, hence they can never be fully anti-war. I would recommend it wholeheartedly to anyone interested in sectarian conflict or Irish history.