What they call France here is the land beyond the Loire, which to them is a foreign country.

Jean Racine, 1662

The year is 1941. The location a nightclub and gambling den in French Morocco. A group of boorish German officials are belting out a loud piano rendition of “Die Wacht am Rhein”, to the forlorn disapproval of the rest of the patrons. With the tacit approval of the proprietor, Paul Henreid instructs the house band to play “La Marseillaise”.

Such is the set-up for one of the most emotionally powerful scenes in cinema history, from the 1942 film Casablanca. The location of the scene, the nationalities and loyalties of the characters, and the time and place in history of the both the story and the film’s production all combine in those emotions. The anthems being sung by each nation’s citizens — France and Germany — are given new context amid global war and the occupation of the former nation’s homeland by the army of the latter.

Both “La Marseillaise” and “Die Wacht am Rhein” were originally written at a time of national awaking. In implicitly identifying their people with their nations, they implore the former to fight for the latter. It is no coincidence that both songs reference the Rhine River, long thought of as representing the natural boundary between France and Germany.

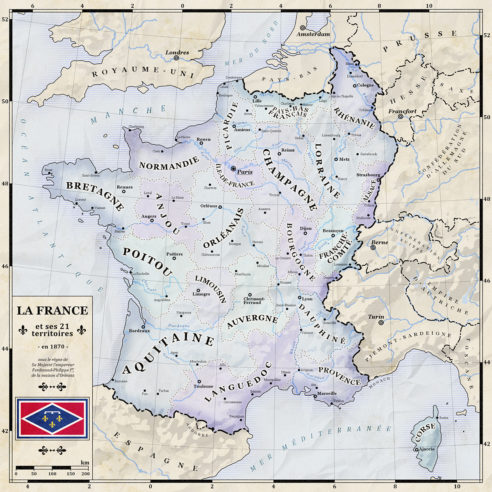

In our history, a powerful French state has been a near-constant of the European map since the Dark Ages. Modern-day France exists within the limits of physical geography. She is bounded by sea coasts and by the ranges of the Pyrenees, the Alps and the Jura mountains. Only her eastern frontier is less clearly defined.

But how inevitable is the emergence of this powerful, unified French state? Does geography make l’Hexagon inevitable? What limits does geography set for an alternate France?

Charlemagne’s legacy

The roots of modern France lie in pre-Roman Celtic Gaul, but the first identifiable precursor to the French nation-state comes with the fifth-century invasion of the Franks and with their establishment of Romanized Germanic dynasties and kingdoms. The most prominent of these dynasties were the Merovingians and Carolingians, and it was as part of the latter dynasty that Charlemagne created his empire stretching from Spain to modern Czechia and Denmark.

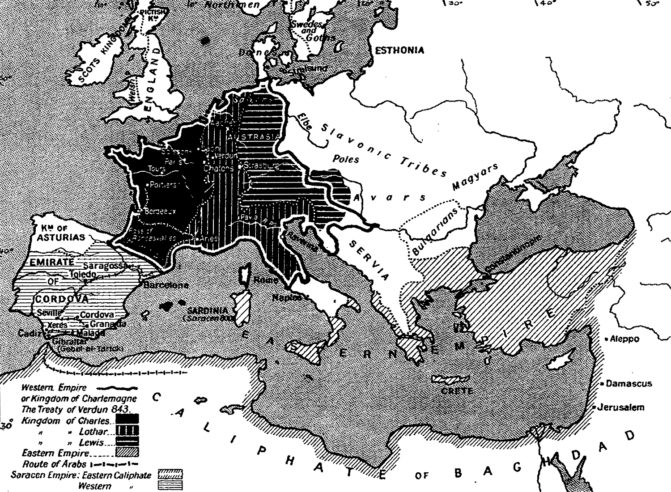

A period of bitter civil war over inheritance followed Charlemagne’s death, ending only when the Treaty of Verdun (843) formalized the division of the empire between his heirs. In heavily simplified terms, Verdun established the division between “France” and “Germany” as separate post-Roman nations with their common frontier originally upon the Rhône and Saone Rivers. History would see the original powerful core of the German kingdom weakened and decentralized — monarchs who subsequently held the title “King of Germany” would often derive their true power through other means (be those Spanish gold, Papal sanction or Prussian arms).

By contract, the French monarchy grew from a modest base to become more powerful as the centuries passed, all the while accumulating more territories and expanding to fill out the modern “hexagon”. A weakening of the Holy Roman Empire in the thirteenth century allowed French kings to expand their realm eastward toward the Alps. Recurring wars with England, while temporarily weakening the power of medieval France, ultimately allowed for a consolidation of power in the crown itself. Aquitaine, Burgundy and Normandy were all conquered or else subordinated, bringing substantial revenues to the crown. Somewhat cynical exploitation of the papal crusade against Cathar heresy in Occitania further allowed the French king and his northern nobles to expand their territories into the wealthy lands south of the Loire. Nominally independent states like Burgundy and Brittany — in the habit of acting independently at times of French weakness — became integrated over the centuries, being downgraded from kingdoms to mere duchies and stripped of local privileges.

At the close of the Middle Ages, a resurgent France was surrounded through inheritance by the domains of the Hapsburg rulers of Spain and Austria, whose possessions in the Netherlands, Rhine valley and northern Italy almost completed that encirclement. France’s position was one of both weakness and strength, as felt and exploited during the Thirty Years War. A clear military incentive existed then for France to set her southern frontiers against Spain and Hapsburg Italy upon defensive mountain ranges, and to push her eastern border with the remaining Hapsburg realms as far east and removed from Paris as possible.

Typically thereafter the dominant great power of Europe, France found herself the target of alliances of containment and convenience as signed between other powers. Some of her farthest eastern territorial advances of the seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries were pushed back with France by now assuming close to her modern shape. The posited long-held dream of Louis XIV — that of a French border on the Rhine — would not be fully achieved until the time of Napoleon, and then only for a matter of years. The defeat of Napoleon and the 1815 Congress of Vienna set the borders of nineteenth-century France with the most significant changes coming with Italian and German unification.

A series of diplomatic crisis — the mood music of 1815-1914 Europe — occurred along the Franco-German border. The Rhine Crisis of 1840 inspired the poem which became the song “Die Wacht am Rhein”. The Luxembourg Crisis very nearly triggered war between France and Prussia, as indeed war was soon after provoked by the Hohenzollern candidacy. Defeat in the Franco-Prussian War saw much of Alsace and Lorraine transferred to the new German Empire, with Revanchism over the lost territory lasting through until the First World War.

Though happy to rebadge the expansionist designs of the Bourbons, French revolutionaries did do away with a mosaic of royally owned semi-states and reorganized what had been a sub-feudal state into a single unitary nation. By the late-nineteenth century, substantial efforts were being made to erase linguistic differences across the Metropole. In schools, punishments were administered for children caught speaking Occitan, Basque or Breton over Parisian French. Assimilationist policies sought to develop a collective French identity at the expense of regional minorities, and these were broadly a success: from being a minority language within France at the time of the Revolution, by 1860 some 80 percent of the national population could speak standard French.

A series of factors, eventually self-sustaining, drove the development and growth of the French state to its historical dimensions. Rich agricultural land supported a large population. A political and cultural heritage inherited from both Classical and Germanic traditions established the nucleus of a state which would go on the acquire more territory and power over the centuries. Historical circumstance conspired to give French leaders opportunities to expand that state, or else to recover from reverses. But the question for alternate history as always remains: how might it have gone otherwise?

Holy Frankish Empire

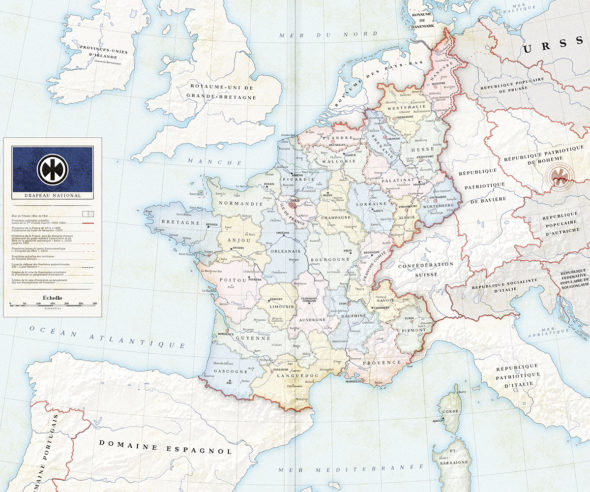

It’s a classic alternate-history scenario: the switch. What if, following the division of Charlemagne’s empire, it had been the territories of the left bank of the Rhine, and not those of the right bank, that fell into a thousand tiny statelets?

After all, Frankish inheritance tradition is right there. Successive divisions and subdivisions of inheritance might have resulted in a map of early modern France more closely resembling a slice of honeycomb than a hexagon.

A decentralized, “balkanized” France might resemble medieval Italy — populous, wealthy and an enviable center for cultural development and political intrigue — but it would not be a European power of military or political significance. The French language might still serve as a lingua franca, but there would be no Francophonie as in our history. French outside of Europe would be the language of a diaspora and not that of a colonial empire.

Of course, without the actions of a latter-day French Garibaldi, there likely won’t even be a single French language. A “France” united as one nation by the romantic nationalism of the nineteenth century will be very different to the republic that developed in our history.

This further assumes that unification would still ultimately come from within. Perhaps instead it would fall to a well-intentioned cartographer to mediatize the Merovingian mess?

Langue d’oïl versus langue d’oc

For a less extreme scenario, what about the historic division of modern France, that between the north and south?

The creator of a timeline should be wary about interpreting these divisions too strongly, else a dozen clichéd secession maps might follow. That said, there is a significant historical difference between northern and southern France, most prominently in linguistics. There would have been no single uniform Occitanian language, but a distinct language/dialect continuum can at its broadest be traced from Catalonia to Gascony and across to Provence.

In our timeline, this part of France enjoyed significant political autonomy up until the time of the Albigensian Crusade and even afterward remained culturally apart from the rest of the metropole, until revolution and nationalism drove the nineteenth-century push towards Francization.

In a world where Catharism survives, or else where the kings of France lack a similar justification to fully integrate the south, might the Age of Nationalism herald not Francization but instead the awakening of a separatist Occitan nationalism more potent than that of our own history? Might a single Occitanian emerge which, contrary to the rules of “natural frontiers”, straddles both sides of the Pyrenees?

Die Wacht am Rhone

But suppose an alternate France does cover both the north and southwest of the present state; where else might her limits be set? The integration of Provence and much of southeastern France into the greater metropole is as much a product of the dynastic rivalries of the Middle Ages as it is any notion of geographic determination. Had any of those rivalries played out differently, the territory east of the Rhône might instead today be part of a surviving independent Burgundy, a united Greater Italy or else an Aragonese-Catalan nation which stretches all around the Gulf of Lion.

A France bounded by rivers all down her eastern frontier has considerable implications for French national policy. Without Provence, France is not tied to the Alps and perhaps has less incentive to precipitate or intervene in wars across the Italian Peninsula. This France would also be more vulnerable to invasion from any power able to project itself from within that peninsula.

No Provence means no Toulon — and that means a much reduced or non-existent France as a naval power in the Mediterranean. In our own history, French naval strategy has often been at a disadvantage due to the need to combine both the French Atlantic and Mediterranean fleets to offset the local supremacy of a rival power, typically Great Britain. This need left French fleets vulnerable to being blockaded or else bottlenecked at the Strait of Gibraltar. A French navy limited by circumstance only to Atlantic harbors might through concentration of forces find itself at an advantage in exerting French power across the Atlantic Ocean, the English Channel and the North Sea.

Conversely, without Toulon and the ability to project power from a Mediterranean base, French influence in North Africa and Egypt would not exist as in our timeline. Egypt might be an exclusively British protectorate from earlier in history or else she might fall to some other power. The Rosetta Stone might never be discovered without the actions of a Corsican general and hieroglyphs might remain forever undeciphered. Without a Mediterranean interest, Corsica itself would likely never come into French possession. Perhaps the island remains an independent republic to this day, or instead provides fodder for discussion on obscure websites about how many British MPs the island would have received if the 1956 referendum result had been accepted.

Without a Mediterranean France to prop up the sultan, Russian ambitions upon Constantinople might be realized in the nineteenth Century. Other great powers might also profit from the power vacuum in the middle sea. Perhaps in another timeline that iconic scene from Casablanca is reversed entirely?

The territorial and political evolution of modern France into a unitary state bounded by (mostly) natural borders appears to be inevitable in hindsight, however, that geographic course was set as much by historical circumstance and dynastic fluke as by any natural imperative. France being a power — indeed the European power — for much of her national history has both driven and been driven by her territorial expansion and centralization. As a result, it should be clear that, given any particular divergence in that evolution in another timeline, l’Hexagone might assume a very different shape indeed.

But while we’re talking of natural imperatives, what of a nation of a rather different character; one whose destiny of territorial expansion seemed so evident as to be spoken of in such terms even at the time? Will this be an example of geographic determinism — or will the reality be rather less manifest? Find out next time…

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.