If otherwise mountains had arisen, rivers flowed or coasts trended, then how very different would mankind have scattered over this tilting place of nations.

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803)

Last time we discussed whether it was by fluke or fate that a single United Kingdom had come to occupy the island of Great Britain. The UK being able to set most of her borders upon the shoreline has proven something of a geographic and historic advantage, one many other states and nations lack. What options remain for less blessed lands? Natural borders perhaps?

A “natural border” is a border between states that follows natural geographic features (rivers, mountain ranges, coastlines). But just how “natural” are natural borders? Say you’re creating an alternate-history map or else worldbuilding for a story or timeline: should the nations on your world map be created with semi-random borders in the interests of maximum divergence from our timeline? Or should their borders instead snap to natural features wherever possible — in effect converging to where these have occurred in our own history. Is there something inevitable about natural borders that makes them more likely to arise in any timeline? Does physical geography even hold so strong a control on borders in our own timeline?

History of natural borders

If like me you’re a bit of a map geek, and have further spent far too much free time playing strategy games, you’ll be familiar with natural borders. The current world map is dotted with them — the Pyrenees between Spain and France and the Andes between Chile and Argentina are obvious examples of borders set along mountain ranges. Rivers like the Rio Grande between Mexico and the United States and the Mekong between Thailand and Laos are similarly used, with the precise line along the middle of their stream marking the official border.

In strategy gaming and alternative-history mapmaking, a common goal for the purposes of immersion — indeed plausibility — is to give states “plausible” looking borders and to avoid “border-gore” (ugly-looking borders). Aiming for natural borders like rivers seems an intuitive way to do this. Of course, this can be taken too far…

It is easy to see how an idea like natural borders arose. From the time that states first developed as the preeminent division of human society, and further once those states began to build up their own foundation mythology through nationalism, it seems inevitable that there would follow attempts to justifying the extent and expansion of a given state’s territory.

Natural borders are more “real” because they are written in nature — impartial, indelible and assigned legitimacy by divine providence. This idea appeals to a “common sense” understanding of the world, that borders should be drawn where nature herself has set them. A straight line on a map is “artificial”. A wiggly line following mountain peaks is not.

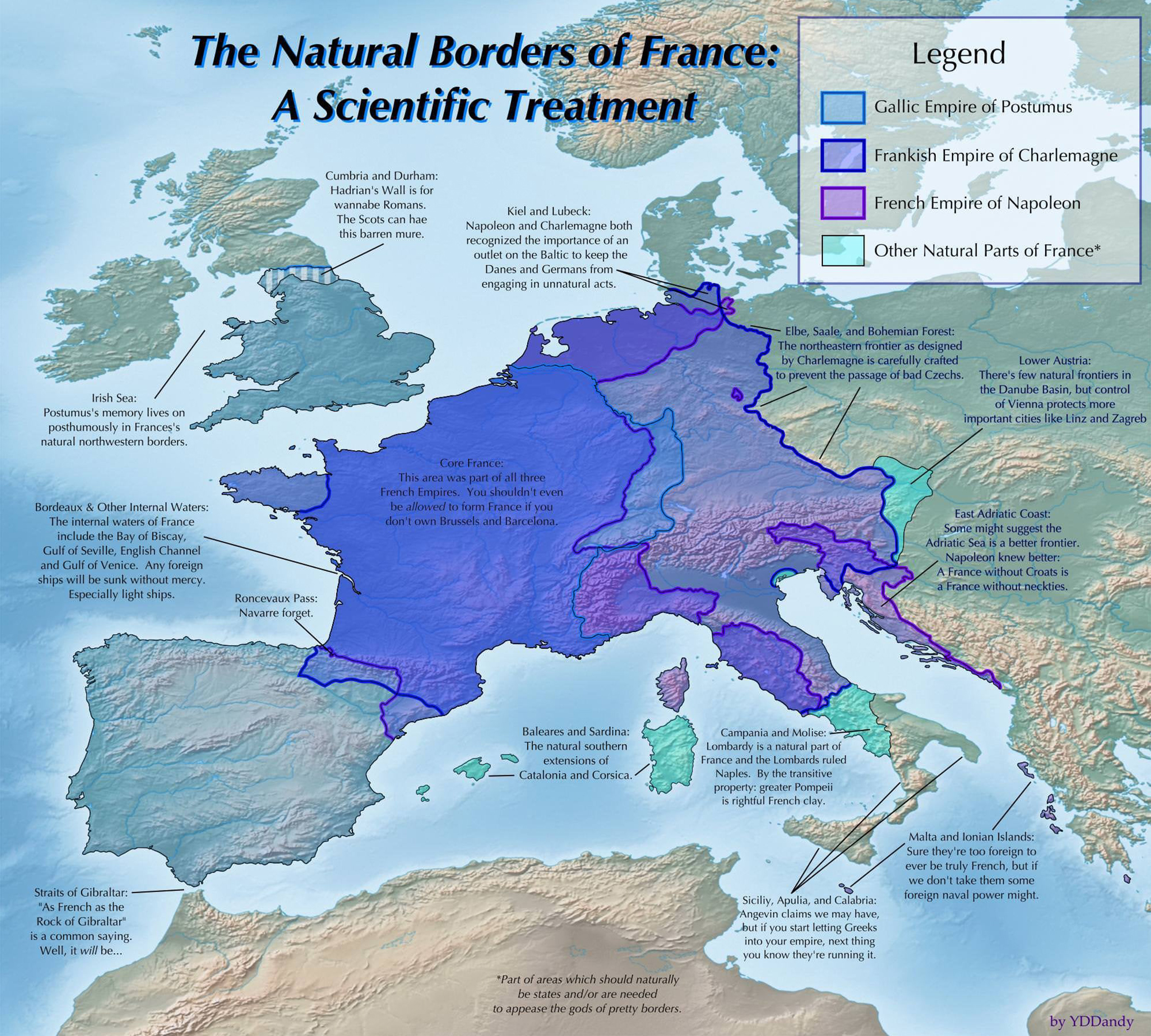

Natural borders, or limites naturalles, became an influential idea in eighteenth-century Europe, particularly in the France of Louis XIV. Coincidentally, France was undergoing a period of territorial expansion at this time. To speak of natural borders was to invoke natural law, an authority higher even than history or legal precedence — which is all rather convenient when planning a war of conquest.

The end of the ancien regime didn’t kill off the the idea of natural borders. Indeed, it quickly became a central Jacobin tenet that nature’s designs were far more egalitarian than the former “unjust” hereditary boundaries. A century later, the former viceroy of India, George Curzon, would write of “natural and artificial frontiers,” with the implication that natural boundaries were intrinsically more appropriate than those not based on the physical landscape.

To this day, the idea that somehow natural borders are better, or indeed more likely to arise naturally if a region is spared outside interference, is a potent one. A century of conflict in the Middle East is simplistically attributed to European-dictated frontiers, a.k.a. “lines on a map,” when the region’s deadliest conflict since the First World War, the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88), occurred over a frontier agreed between the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Persia in 1639. Serious economic papers have been written attempting to claim that the prosperity of a country has a meaningful correlation to how “squiggly” its borders are.

Regardless of whether natural borders are an intrinsically “good thing”, are they more plausible or likely to arise than corresponding “artificial borders”?

The case for

The obvious argument for natural borders comes from their inherent strategic use. A frontier set upon an impassible mountain range or along a deep and fast flowing river provides a barrier against the movement of hostile armies, far more so than a straight line drawn through an open plain. It follows that nations, especially those primed to be on the defensive against invaders, will aspire to set their frontier at these natural features.

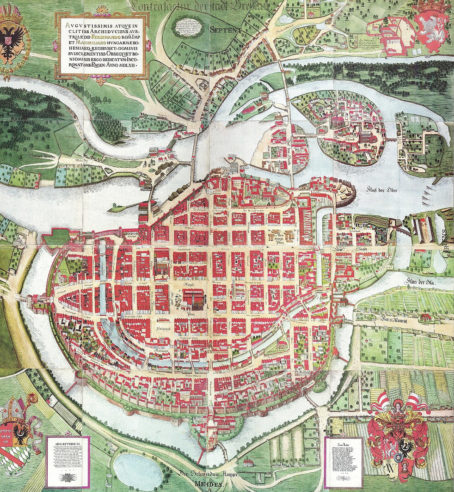

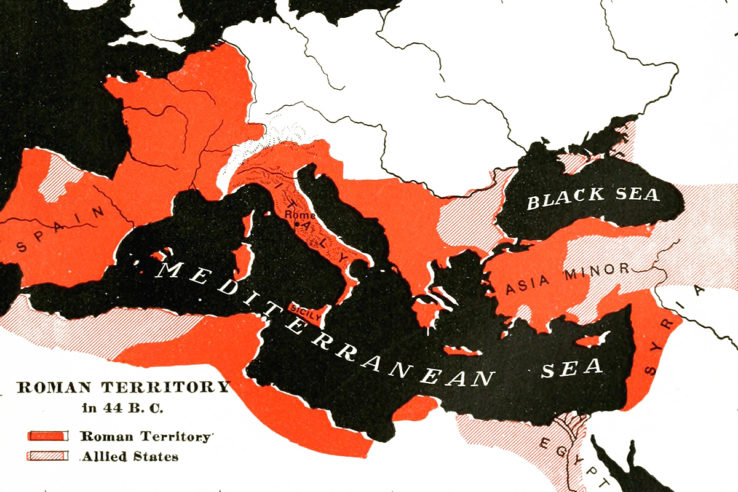

The expansion of Ancient Rome from one natural barrier to the next, ultimately settling on a frontier formed by the Rhine and Danube Rivers, is a prominent example of a strategic natural border.

Likewise, Czechoslovakia’s interwar defensive plans hinged upon their natural borders as set by the Sudetes with pillboxes and other defenses being built in the hope of resisting a future German invasion. Given the choice between a defensible border and one which advantages their enemy, wouldn’t any nation in history, or alternate history, aspire to such perceived security?

Borders which follow natural features have arisen across the globe at all times and places, wherever settled peoples have formed into organized states. Justification for natural borders has been sought through nationalism or by appealing to concepts of Volk, as in eighteenth-century Europe. Alternatively, in China the idea of natural zones of control arose around the same time. There is a long history of attempts within political geography to reveal links between topography and states or boundary. If the concept of natural borders has arisen — you might say “naturally” — in our timeline, might it not do so in any other?

Natural borders are practical, not just to the alternate cartographer, but to the surveyors and diplomats who have endeavored to set borders in our own history. When it comes to drawing lines on a map, it’s easier to draw these where there are already lines, especially if there is interest in settling the matter quickly and definitively without too much care as to the situation on the ground.

An accurate means to measure longitude was not widely available until long after the historical age of exploration with the result that many early maps show the American continents stretched east-west far beyond their now-known limits. The straightforward papal mediation of Spanish and Portuguese claims via the Treaty of Tordesillas, into “Old” and “New World spheres”, was rather spoiled by the South American continent’s insistence on extending further eastward than first assumed. Even on land, notionally straight borders, such as that between the United States and Canada along the 49th parallel, are in practice defined by the historical markers of imperfect surveyors. At local scale, such borders more closely assume a zig-zag course of cumulative human error than the geometric ideal.

The United States as a single entity has been defined by natural borders during its early history. The original Thirteen Colonies, whatever their notional “sea-to-sea” charter claims, were in practice bounded by the crests of the Appalachian Mountains, from Georgia up to Pennsylvania, and by the Green Mountains and the wilderness of the St Lawrence River in New England. After independence, the frontier became for a while set upon the course of the Mississippi and thereafter at the western limits of that river’s drainage basin. The present day American border with Mexico in part follows the course of the Rio Grande. The border with Canada is the exception that had arisen only after decades of negotiation and dispute.

Mountain borders form some of the oldest and most continuously maintained borders in the world. The current Pyrenean mountain border separating Andorra from France and Spain was fixed by feudal charter in 1278 and has remained so ever since. Similar barriers, separating Italy from the rest of Europe, India from the rest of Asia and Magyar Hungary from Slavic kingdoms to the north, east and south, have consistently arisen throughout our history. It seems highly likely that they would favor similar borders in any alternate history.

The case against

In practice, rivers make awful borders. While they may indeed make for good frontiers, in far away, badly defined and scarcely populated lands, they are far less useful in densely populated countries.

The city of Wrocław on the Oder River — otherwise known as Wrotizlava, Vratislavia, Vretslav, Presslaw and Breslau — has in its long history been home to a multitude of different cultures, religions and languages. It has been incorporated in every major state to dominate central Europe, from medieval Poland to Nazi Germany, and yet could never have been said to belong firmly and homogeneously to any of them. No attempt in history to set a border along this particular stretch of the Oder could have “naturally” divided this city, nor apportioned it to one state or other. Populations mix and river valleys are as much channels for communication and trade as they are barriers. Two communities on opposite banks will often have stronger mutual ties than will either with the peoples inhabiting distant uplands on their same bank.

The Rhine is commonly spoken of somewhat partially as being a “natural border” for either France or Germany. While this reading appeals to the notion of a frontier against an “other”, it ignores the centuries of intertwined commerce and culture of our history’s Rhineland.

Further, the fluid and evolving nature of feudal obligations over that history created an entangling of German and French feudal hierarchies across the border region, further blurring the line as to which areas were “naturally” of one side or the other. It took the upheaval of the Napoleonic Wars, and two further world wars, to settle the lasting borders of Western Europe — of which the Rhine provides only a small segment.

Rivers also by their very nature tend to move. This can be the incremental effect of ongoing erosion and deposition along their courses or else the abrupt change of a flood event leading to an entirely new course. If that river sets a border, then inevitably this border will also be seen to have moved, in turn a cause for conflict between states that might have otherwise felt secure behind their “natural borders”.

Just such a conflict — the Chamizal Dispute — arose between the United States and Mexico over the shifting course of the Rio Grande. The dispute took the better part of a century to resolve and almost resulted in the dual assassination of two nations’ presidents.

For added irony, as part of the resolution to the dispute, both nations agreed to build a man-made channel to prevent the Rio Grande from shifting in the future, thereby keeping the border permanently fixed. A natural border became a distinctly man-made one.

A similar problem, though more easily resolved, occurred when navigational improvements to the course of the River Meuse left parts of Belgium on the Dutch side of the river and vice versa. With Dutch police having no jurisdiction over these enclaves, and Belgian police having no easy access by which to enforce the law, the areas in question degenerated into lawlessness, until a land swap could be arranged fifty years later.

For every major river that forms a political border, there are dozens that don’t. The Nile, a river which might be more closely tied to one particular polity than any on Earth, has never been set as a border between different realms. The Danube flows through states and at times major empires. While parts of it form borders, such as between Slovakia and Hungary, and the historical northern border of the Ottoman Empire, the river serves as much to tie disparate lands together. Four capital cities are on the Danube and parts of Germany, Austria, Hungary and Serbia sit on both banks. The Huang He River is seen as part of the Chinese heartland and not as a frontiers on which a border might be set, were that its frequently shifting course could make that possible.

Just as better surveying techniques have made it easier to set geometric or other “artificial” borders, so have they made it easier to dispute natural borders. A new survey of mountain peaks may shift the border line or else disputes may arise over exactly what counts as an island for the purposes of setting territorial waters. Rivers that are assumed to follow a certain course in their unmapped headwaters at the time a treaty is signed may afterwards be discovered to be less than cooperative.

Technological advances also enable rivers to be crossed or bridged more easily and for mountain passes to be discovered and opened up to higher traffic all year round. Hannibal leading elephants into Italy would conjure up a somewhat different scene if the Carthaginian general were able to make use of tunnels through the Alps. The strategic advantages to natural borders have eroded at the same time as those borders have become lesser barriers to human communication.

The fundamental issue with the concept of natural borders is that they are by nature an essentialist argument — an appeal to nature as an authority and as the arbiter of what ought to be. In practice, they only exist so long as the political will exists to maintain them. Natural borders are part of the mythology that has allowed for the idea of a state being equivalent to a geographic place to become institutionalized to the point where it seems intuitive. Germany is both a state and a place, therefore it seems natural that the one should map to the other. Where Germany as a place ends — however those geographic limits can be defined — so should end the limits of the German state. Natural borders allow for these limits to be set in a way that may seem more credible than mere nationalist imperative.

Of course, as a final note, one thing the alternate historian should bear in mind is that nation states are far from the only possible form of socio-political organization. Would their absence from the world make natural borders any more or less likely?

Conclusion

For an alternate historian, already primed to strip away the certainties of determinism, the opportunity is always there to be more critical of any construction that claims to be inevitable. The existence of “natural borders” in history owes more to post-facto justification of territorial ambition, and to a correlation with genuine geographic influences, that to any overbearing influence of topography on political organization.

While the aesthetic urge will always remain to produce maps with “pretty” borders — ones which perhaps mimic the fractal complexity of natural features — there should be no need to limit borders to these natural features in the interests of plausibility. More of Europe’s interstate borders were created by the Big Three at Yalta in a single afternoon than were ever set in stone by all the mountain building in geological history.

What’s that? I can still hear the words limites naturelles being muttered at the back. Well, I suppose there’s still time for a hexagonal look at the matter next time around.

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.