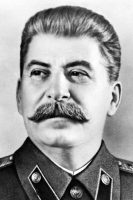

“The world will hold its breath!” is the reaction Adolf Hitler promised when planning the most ambitious conquest of the war he had inflicted upon the world: Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. When it came to pass, the German dictator had been largely justified in making his claim. Barbarossa was the largest invasion of all time and would lead to an existential struggle that, even in the context of the global conflict surrounding it, was incomparably brutal. The fact that the Eastern Front of the Second World War would have been the world’s deadliest conflict on its own is a testament to this fact, and ultimately it would prove to be Hitler’s undoing.

Barbarossa’s aims, strategic, racial, ideological, were designed to be the final culmination of Hitler’s plans for a vast Nazi empire in which there would be ample living space for an expanded German population and sufficient resources to fuel a superpower that would be able to conquer the United Kingdom and eventually go toe-to-toe with the United States. The peoples of the Soviet Union, decreed to be subhuman by Nazi propaganda, were to be deported, enslaved and exterminated to make way for the new master race, with their innate racial inferiority making their lands forfeit to their new Aryan colonists.

The failure of Barbarossa spelled the end of these plans, and made a mockery of the absurdity of Nazi racial doctrine, but also more importantly the supposed invincibility of the German Wehrmacht. The Soviet Red Army was badly mauled but it survived, and from Moscow to Stalingrad to Kursk grew stronger and more resilient until they outmatched their German foe and began to march west in the face of increasingly desperate German resistance, until the red flag was raised above Berlin.

Given the importance of the outcome of Operation Barbarossa in ensuring the demise of the Third Reich, it is only natural that it has been the subject of a great deal of speculation both in questions posed by historical works but also those of alternate history. Given that those of us involved with Sea Lion Press are lovers of both, I thought I would cover five of the most popular “what ifs” that are often discussed about Barbarossa to see whether or not we can draw some conclusions. Or at least generate more discussion about a part of the Second World War that is still poorly represented in popular retellings of the conflict.

So without further ado, let’s jump into the thick of the German invasion and consider a scenario that haunted many in the German High Command as the Red Army was bearing down on Berlin: What if the Germans had pushed onto to Moscow in the summer of 1941?

The crossroads: August 1941

The Second World War has been raging for almost two years and it appears to be reaching a crescendo. Across a thousand-mile front, millions of men and thousands of tanks and aircraft clash in some of the bloodiest battles in history.

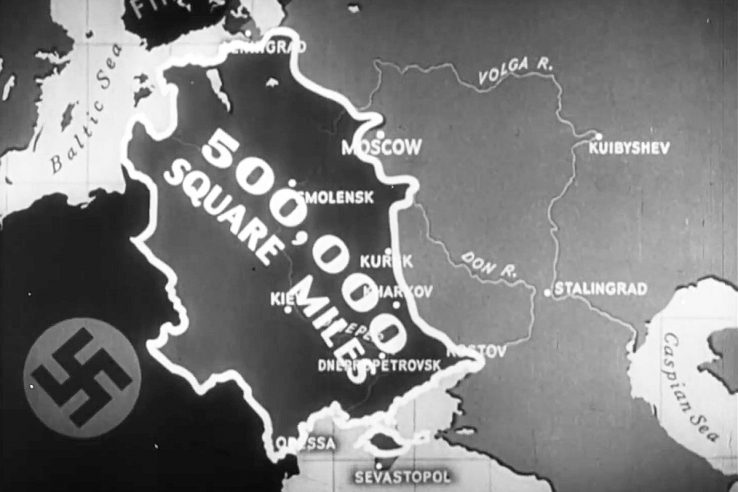

The Germans and their allies in the form of three vast Army Groups to the North, Center and South have advanced over hundreds of miles into the Soviet interior, leaving a trail of blood and devastation in their wake. Minsk and Smolensk have fallen among countless other cities and Moscow is now under threat. The Red Army, outnumbered from the first day of the German invasion, has lost over a million men dead and an even larger number captured or wounded, and many around the world are surprised they have not collapsed altogether. The Soviets have survived this onslaught, but it appears that the Germans may be ready to land a killer blow.

The Germans have paid dearly for their conquests. In the seven weeks since Barbarossa began, they have lost more men killed and wounded than in the entire war previously. This has had a jarring effect on German morale and even among the triumphant fanfare with which every Soviet city is taken the Nazi regime and the German Wehrmacht are not blind to the fact that their losses in men and materiel are far worse than expected. Regardless, they are convinced the conquest must continue regardless of the bloodshed.

Stalin remains defiant, but the situation is clearly desperate. Through superhuman efforts, much of the Soviet Union’s industry has been evacuated east by train to the Ural Mountains and Central Asia, far out of reach of German bombers but also temporarily unable to function to the needed capacity. The Red Army is undergoing a mass mobilization, but raising new armies is a costly and time-consuming enterprise even when not in the midst of an invasion. Many reservists have been captured before they could even put on a uniform.

Hitler is frustrated that the Red Army has not yet been destroyed, but he is confident that victory is within sight. A significant number of the enemy’s surviving troops lay in the south alongside two of the most important goals of the conquest of the Soviet Union: the vast breadbasket of the Ukraine and the oil of the Caucasus. He is adamant that a move south will ensure victory, but many of within the German army disagree, including the majority of the German General Staff and the Supreme Commander of the German Army, Field Marshal Walther von Brauchitsch.

In a memorandum to Hitler on August 18, Von Brauchitsch outlined the broad support among his peers for advancing onto Moscow, where the largest concentration of the Red Army was now preparing to defend the city. Destroying these forces and taking the city would be more advantageous to the German war effort, he argued, as it would not only greatly weaken the Red Army’s strength but also their spirit by taking the Soviet capital. Losing Moscow as a railway hub would also greatly hamper the Red Army’s supply situation, perhaps to breaking point.

Ultimately this suggestion is rejected by the German dictator, who issues a memorandum on August 21 reaffirming his commitment to prioritizing the seizure of Ukraine and the Caucasus to the south and Leningrad (modern say St Petersburg) in the north.

Despite even more German success in the late summer and early autumn of 1941, the Soviet Union continues to fight on, the Germans conquer the Ukraine and although Leningrad is besieged it does not fall. Operation Typhoon, a desperate lunge at Moscow in the late autumn of 1941, spells the end of Hitler’s plans as it grinds to a halt in the fire and snow outside the city before being driven back by an unexpected Soviet counterattack. Barbarossa has been a failure, and although it is not immediately evident in the winter of 1941 it has sealed the fate of the Third Reich.

And we all know what happened next.

Onward to Moscow

The General Staff’s proposal to continue the central advance toward Moscow was more enticing to Hitler than it often seems and was not rejected out of hand despite his repeated insistence on the need to strike north and south first. Historian David Stahel argues that Hitler may have considered the option of Moscow as a superior target even as the German move south was already underway, causing even greater strain to German supply lines that were already reaching their limit.

Whether or not Hitler would actually have ever given the green light to prioritizing Moscow over Kiev and Leningrad is debatable, but given that he at least considered doing so historically it can’t be dismissed as a possibility. With Hitler’s blessing the central advance would have been resumed, at least when Army Group Center was ready to do so.

In his book The Road to Stalingrad (1975), John Erickson points to the fact that by August the German advance in the center had been “bludgeoned to a pause” by the Red Army’s tenacity in defense alongside desperate counterattacks. Even as the German high command deliberated on where to strike next, German troops in the field were having to fight off a Soviet offensive forty miles outside Smolensk without having recovered from the battle that had seen them take the city.

The Germans held, but it was clear that Army Group Center was worn out. Any move on Moscow would have required a pause that might have stretched into late September. Historically, the Germans were unable to stop another Soviet offensive in the Yelnya salient to the southeast of Smolensk in early September and were forced to withdraw from the area. This was the first real Soviet victory against the Germans since the start of Barbarossa and although it has largely been overshadowed by the German capture of Kiev shortly after, in this scenario it would have fallen upon a German army in the midst of recovery and preparation.

David Glantz, the leading Western historian of the German-Soviet war, has pointed out that these offensives were far too costly for the Soviets to be considered worthwhile, but had the Germans been preparing an offensive towards Moscow it’s possible they would have been abandoned, leaving the Soviet defenses far stronger. The Germans, however, likely wouldn’t have been able to rely on the Soviets to stay quiet in the south merely because they had chosen to ignore them. The three armies destroyed in the Battle of Kiev, around 600,000 men, would likely have attacked the German’s southern flank and it’s questionable as to whether or not the Germans could have held them off without having to cancel their plans for taking Moscow altogether.

Assuming the Germans were able to do so, an attack toward Moscow in late September would have seen the Germans entering into a bitter fight with the largest concentration of Red Army forces while holding off Red Army counterattacks from the south and beginning to endure the autumn rains that would begin to turn poorly constructed roads into muddy ditches. Delays would have been inevitable in fighting this battle outside Moscow, buying the city time to prepare for its own defense.

Had the Germans been able to reach Moscow, they likely would have attempted to surround it first, further extending their supply lines, before the ensuing battle for the city descended into desperate urban warfare.

By the winter of 1941, the city may or may not have fallen but the new Soviet divisions arriving from Central Asia and Siberia that led the Soviet counterattack outside of Moscow historically would likely be ready to come to the city’s rescue. With the Germans extended further east than they ever were historically it’s quite possible the majority if not almost all of the German forces that made up Army Group Center would have been cut off and destroyed. This would be Stalingrad a year earlier, only much worse for the Germans.

It’s not difficult to see how the above situation may have unfolded into a catastrophe for the Third Reich, but having examined the potential risks of continuing to advance toward Moscow it’s only right to consider how it might have been a benefit.

Let’s assume that the Soviets continue to wear themselves out on counteroffensives in the center and that any potential counteroffensive in the south is also hampered by a successful defense from Army Group Center and minor attacks from a reduced Army Group South. Let’s also say that the Germans are ready to attack by the middle of September and are able to launch another vast encirclement of Soviet forces like those they had achieved previously and would continue to do so historically. The battle outside Moscow is a decisive German victory and they are able to surround the city before it is properly prepared for defense, and take it shortly after. What happens next?

It’s unlikely that Stalin would have chosen to stay in the city in such a scenario, relocating to the city of Kuybyshev (modern-day Samara) 500 miles east of Moscow, where much of the Soviet government had already moved in fear that the city might fall. Lenin’s tomb along with anything that hadn’t already been taken east would have gone with him. Although the loss of the city would have been a great blow to Soviet morale, Stalin would likely have stressed that Napoleon had also taken Moscow only to be defeated eventually and that history would repeat itself.

As if to emphasize Stalin’s point, Moscow would have burned to the ground shortly after the Germans entered the city as it did with the French. The Soviets had planned to plant explosives within most major buildings within the city including, the Kremlin itself. Even if the Germans could take the city, they wouldn’t be allowed to have it, although this wouldn’t have been much consolation to the Soviets, who would have now faced severe consequences from their inability to hold the city.

With the city being the most important railway hub in the country, the loss of Moscow would have impacted across the entire eastern front and within the interior of the Soviet Union. The Soviet ability to rebuild and relocate that had been so vital to their survival during Barbarossa would have been seriously hampered.

In the north, it’s likely that Leningrad would not have been able to endure the Finnish-German siege of the city without the lifeline that was ultimately reliant on the Soviet Union’s railways. And if Leningrad fell, the Finns and the Germans would also likely have been able to advance on the northern port of Murmansk if they had chosen to. Losing Murmansk would have helped to close the Soviet Union off from the outside world and British and American aid that likely would have become far important in such a scenario.

The prospect of retaking Moscow would be bleak as winter set in, with the Germans able to entrench themselves, establish airfields further east than they could historically, and with the Soviet’s logistical issues it’s likely any attempt may have resulted in another costly failure for a Red Army that couldn’t continue to afford such losses in manpower and material.

In the south, the Red Army forces would have withered on the vine, preparing for the inevitable German attack in the summer of the 1942. Hitler would undoubtedly have insisted that this would be the year that would see the end of the Soviet Union and the enshrining of German hegemony over Europe. The fact that the capture of Moscow had failed to bring about total victory would be forgotten about. While the fate of the Soviet Union still hung in the balance, Operation Barbarossa would have been an unblemished, albeit only partial, success.

A lot of ifs

The Germans opting to advance on Moscow in the August of 1941 could have potentially brought great reward and would have been a disaster for the Soviets had it succeeded — but the strategy requires too much reliance on luck to be considered realistically preferable to the course the Germans took historically and has far more potential pitfalls should the Soviets have resisted as bitterly as they had done in so many instances of those first weeks of Operation Barbarossa.

The decision to move on Kiev and Leningrad was the “safe” option for an invasion already compounded with risk and given the Red Army’s failure to obligingly cease to exist after the first few weeks of the German-Soviet War, it is perhaps understandable that Hitler realized his luck may be changing. With hindsight, it is interesting to speculate on how different decisions may have changed the prospect for a German victory, but when considering the option for Moscow one thing becomes abundantly clear: Barbarossa was always going to fail.

Or was it?

Find out next time!

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.