A monumental elephant in place of the Arc de Triomphe. An aerodrome in the Jardins de Bagatelle. Multiple Eiffel Towers. Take our tour of the Paris that never was!

Paris in the Twentieth Century

Jules Verne’s Paris in the Twentieth Century (written in 1863 but not published until 1994) was rejected by his publisher for being too far out-there, but actually got many things right. His 1960s have cars, skyscrapers, underground trains and a network of computers that can be used to send messages. Women work the same jobs as men and have children outside marriage. Entertainment is dominated by nudity and sex. For most people in the 1860s, this would have been totally incredible.

Unlike Verne’s earlier and later books, Paris in the Twentieth Century is a dystopia. The protagonist is a romanticist disappointed in the modern world.

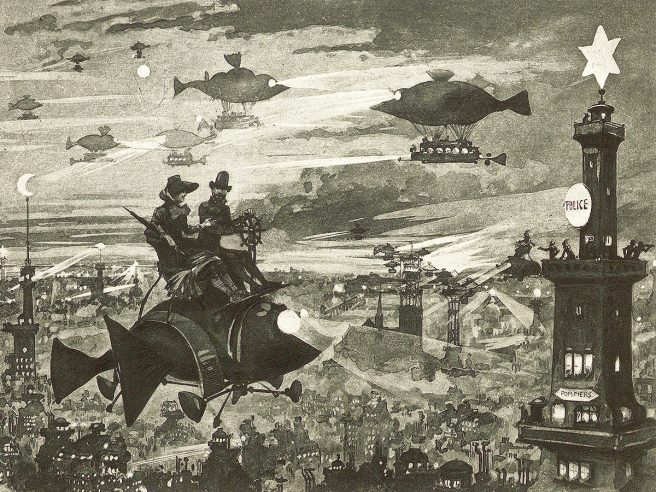

Verne’s contemporary, Albert Robida, imagines a happier, but less futuristic, twentieth-century Paris in Le Vingtième Siècle (1883). The streets are filled with smog and the skies are full of dirigibles. Police towers dot the skyline to keep an eye on the nighttime traffic.

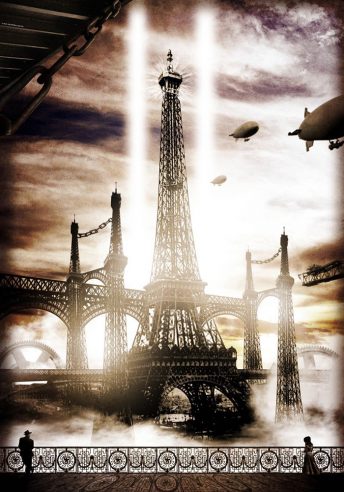

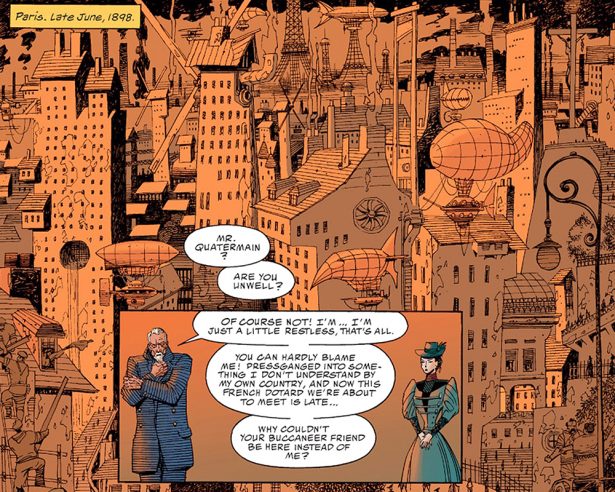

The Paris in Alan Moore’s and Kevin O’Neill’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is something of a homage to Verne’s and Robida’s. The sky is full of smog and dirigibles and there appear to be several Eiffel Tower-like structures on the horizon.

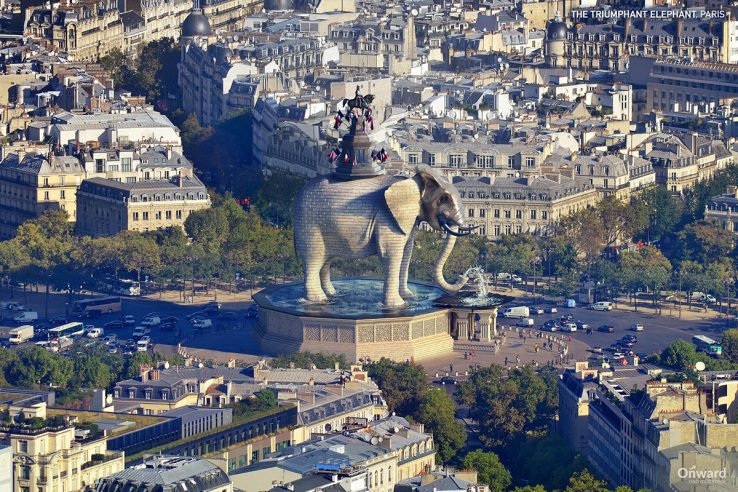

Monumental elephants

Paris could have had two monumental elephants. The first proposal dates from 1758, when architect Charles Ribert drew up plans for a giant elephant statue in central Paris. It would have water coming out of its trunk and music coming out of its ears, courtesy of an orchestra inside.

A full-scale plaster model of the Elephant of the Bastille was actually built in 1813. The monument was sponsored by Napoleon, but construction on a bronze version stopped when he was defeated at Waterloo in 1815. After rats took up residence in the plaster version, it was torn down in 1846. The July Column now stands where the elephant once did.

Eiffel Towers

Stephen Sauvestre’s contributions to the Eiffel Tower are largely forgotten, but he was responsible for designing the decorative arches at the base, the first-level glass pavilion and the cupola at the top.

His own design was even more ornate, with various domes on the first level and two supporting towers.

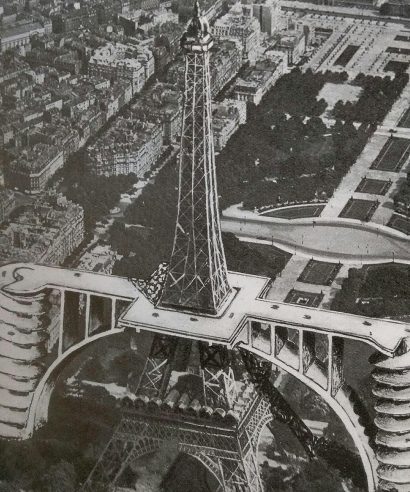

In 1936, André Basdevant proposed adding two ramps to either side of the tower to enable cars to reach the second level.

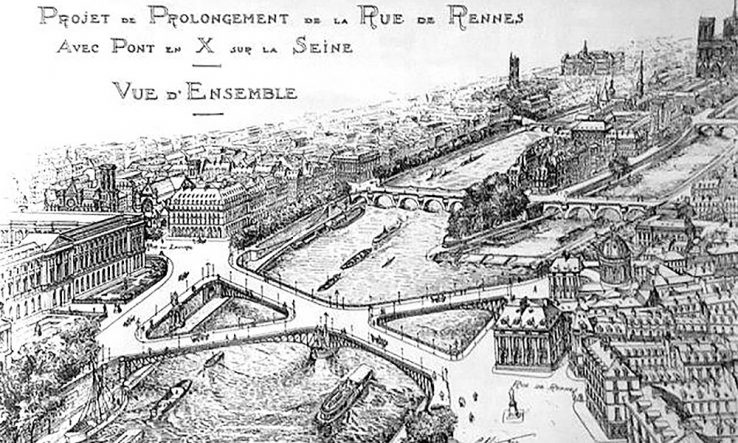

Bridge X

Architect and urban planner Eugène Hénard was obsessed with improving traffic flow in Paris. He called for a ring road around the city and two new thoroughfares meeting at the Palais-Royal that would have divided the capital into four districts.

His plan included an X-shaped bridge across the Seine just west of the Île de la Cité.

It was never built, but Hénard was given the chance to redesign the Place de l’Opéra. Construction on a ring road didn’t start until after the Second World War.

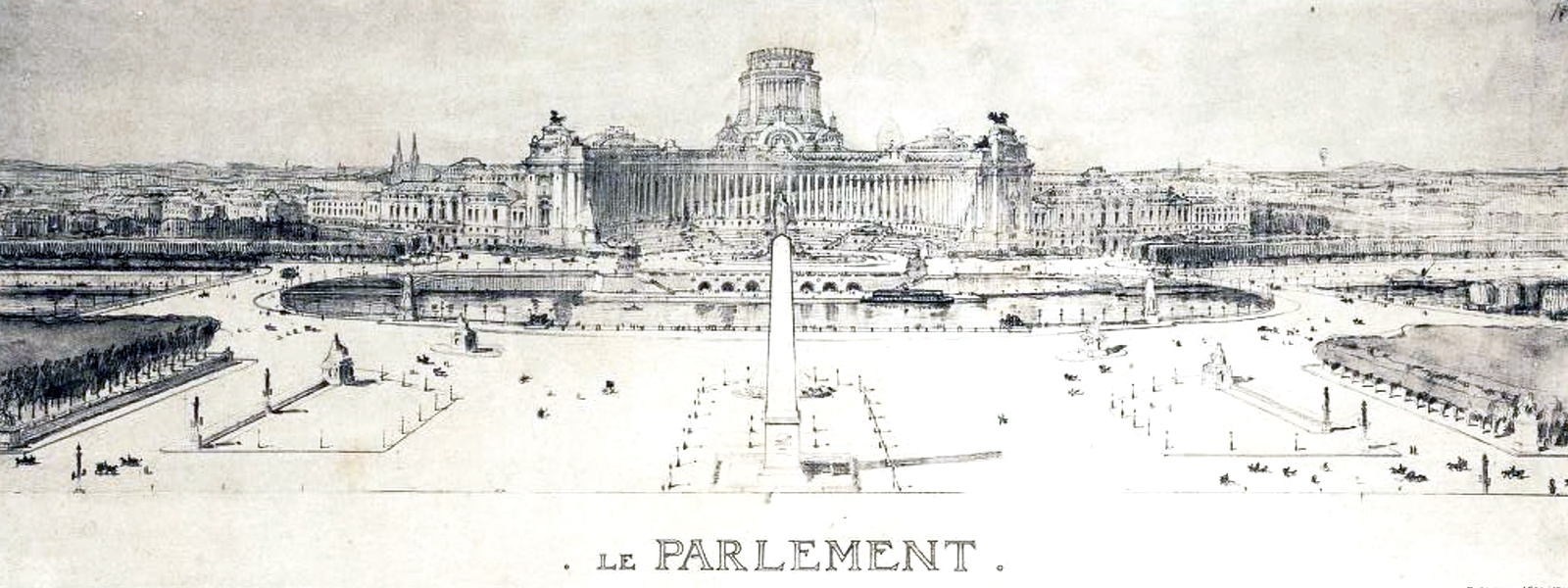

New parliament

Around the turn of the last century, the Bourbon Palace, across the River Seine from the Place de la Concorde, was considered too small to house the French parliament, which had doubled in size.

Étienne Coutan, then a young architect, proposed demolishing the palace and replacing it with a vast and monumental structure that would have dominated the Paris skyline.

Open air theater

Before he became an architect in the Art Deco style, Adolphe Thiers (not to be confused with the first president of the Third Republic) proposed replacing Square Barye on the eastern tip of Île Saint-Louis with an open air theater.

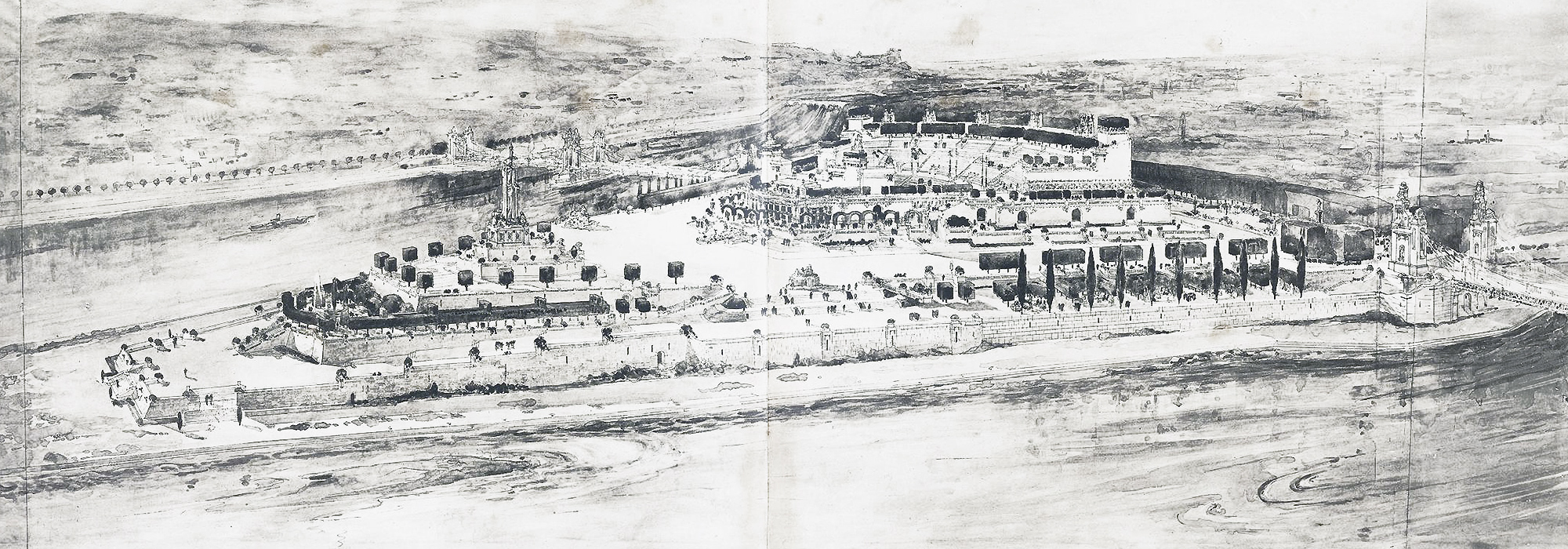

Palace of the People

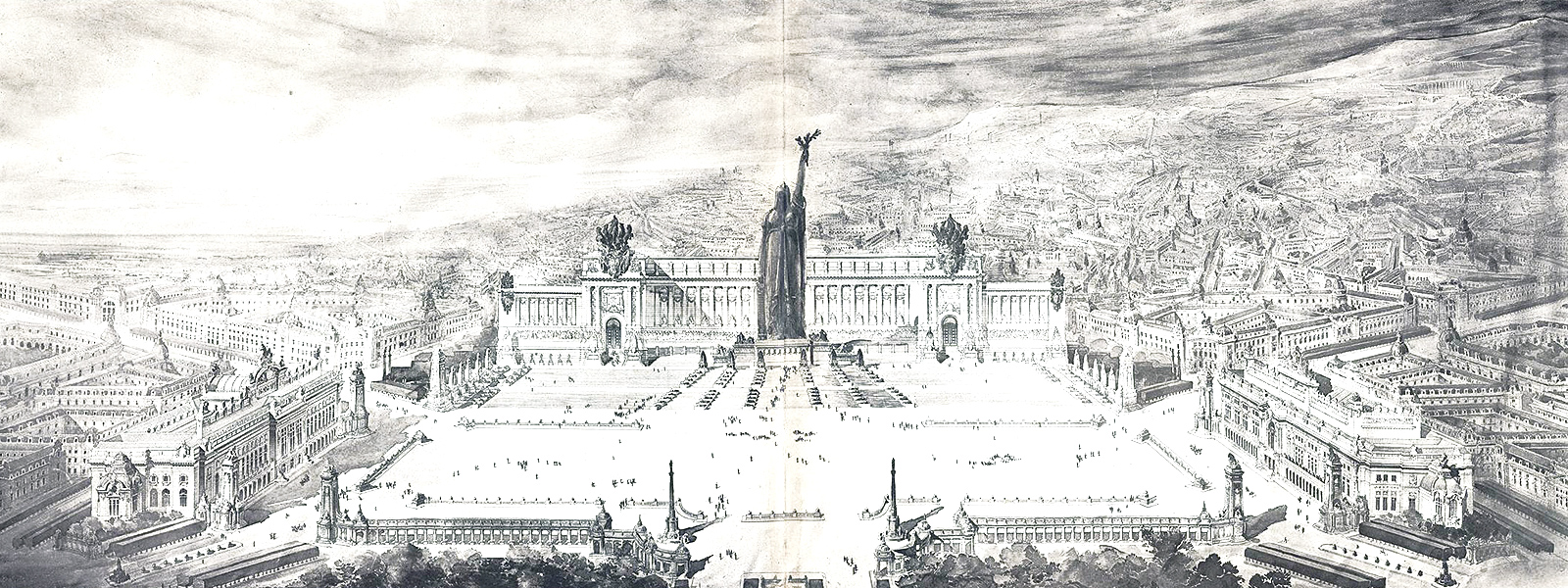

As a young architecture student, Léon Jaussely — who would go on to author the most significant revision of Barcelona’s urban expansion plan, the Plan Cerdá (also see Unbuilt Barcelona) — dreamed up a Palace of the People for Paris, built north of a vastly expanded Place de la Bastille.

The column in the center of the drawing is the July Column, which was erected in 1835-40 to commemorate the July Revolution.

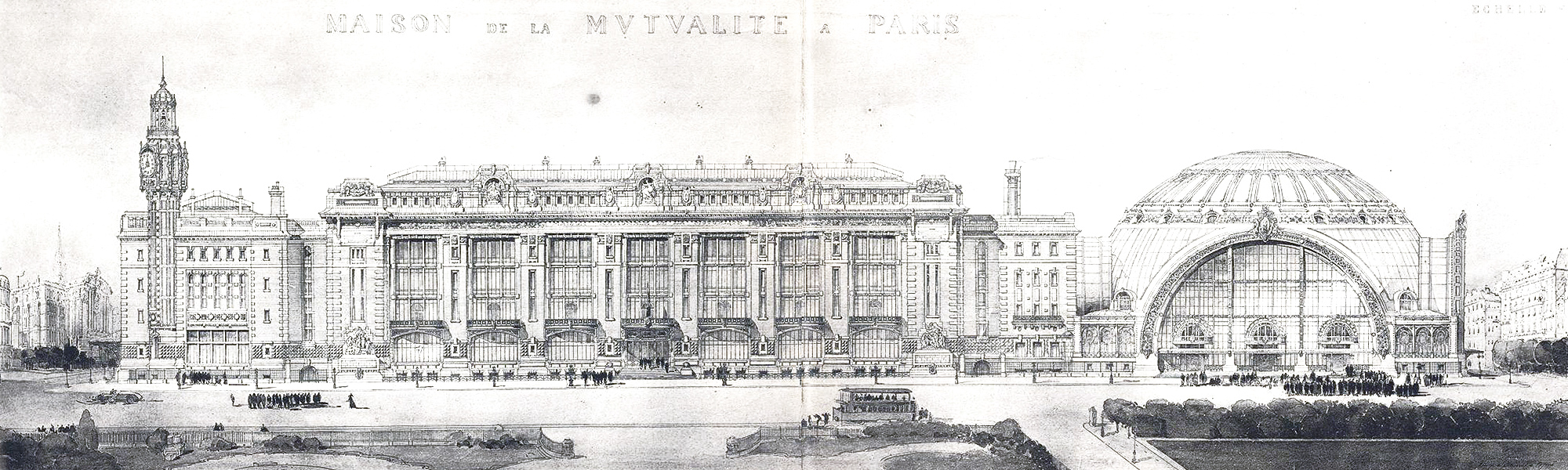

Maison de la Mutualité

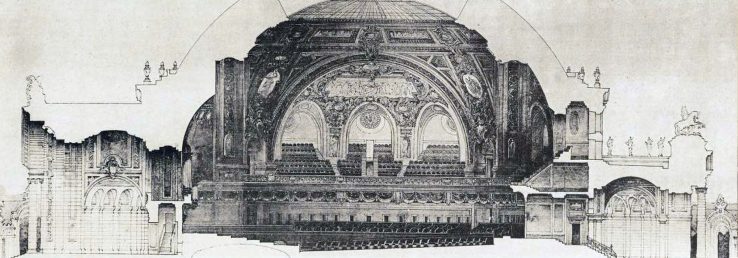

The Maison de la Mutualité was built in the early 1900s in the Art Deco style. If architect Henri Ebrard had had his way, the theater and conference hall would have been done in the more traditional Beaux-Arts style instead.

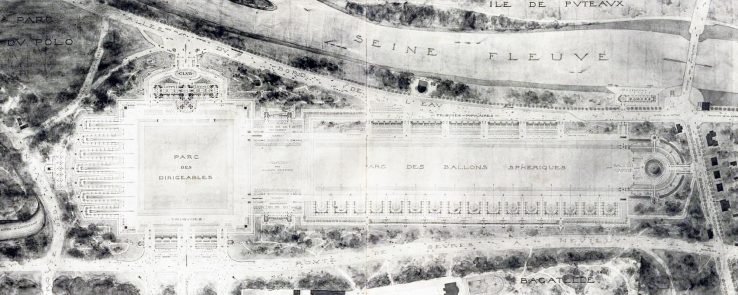

Aeroclub

The fact that this wasn’t built must be steampunks’ biggest regret: an “Aero-Club”, or aerodrome, west of Paris in what are now de Jardins de Bagatelle. The designer was Henry Bans.

Newspaper office

Little is known about this drawing, except that it was entered into a competition for the design of a Paris newspaper office.

The byline credits a “Laprade”, which suggests the architect may have been Albert Laprade, who started his career in the studio of René Sergent, a Louis XV-style specialist.

Laprade’s own style became more modernist after the First World War. Starting in the 1930s, he became a well-known advocate of town preservation and restoration.

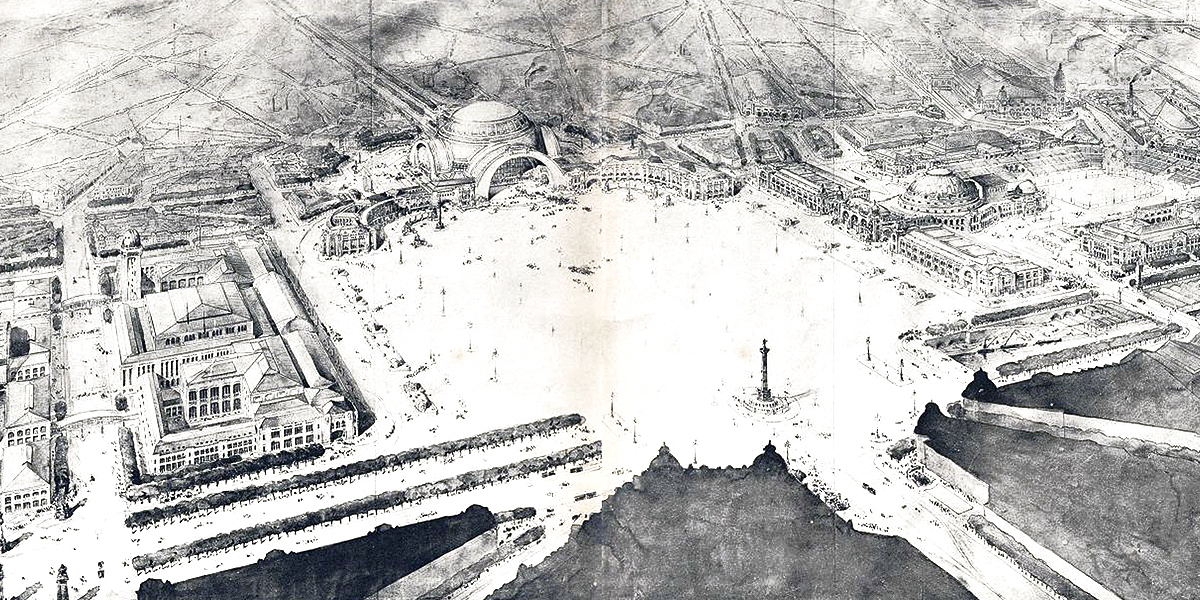

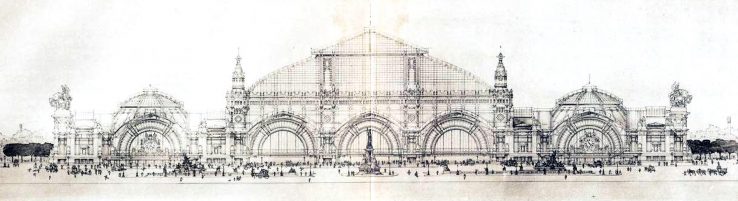

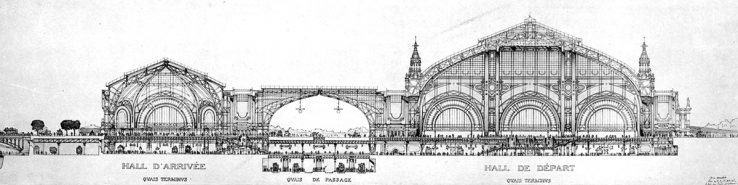

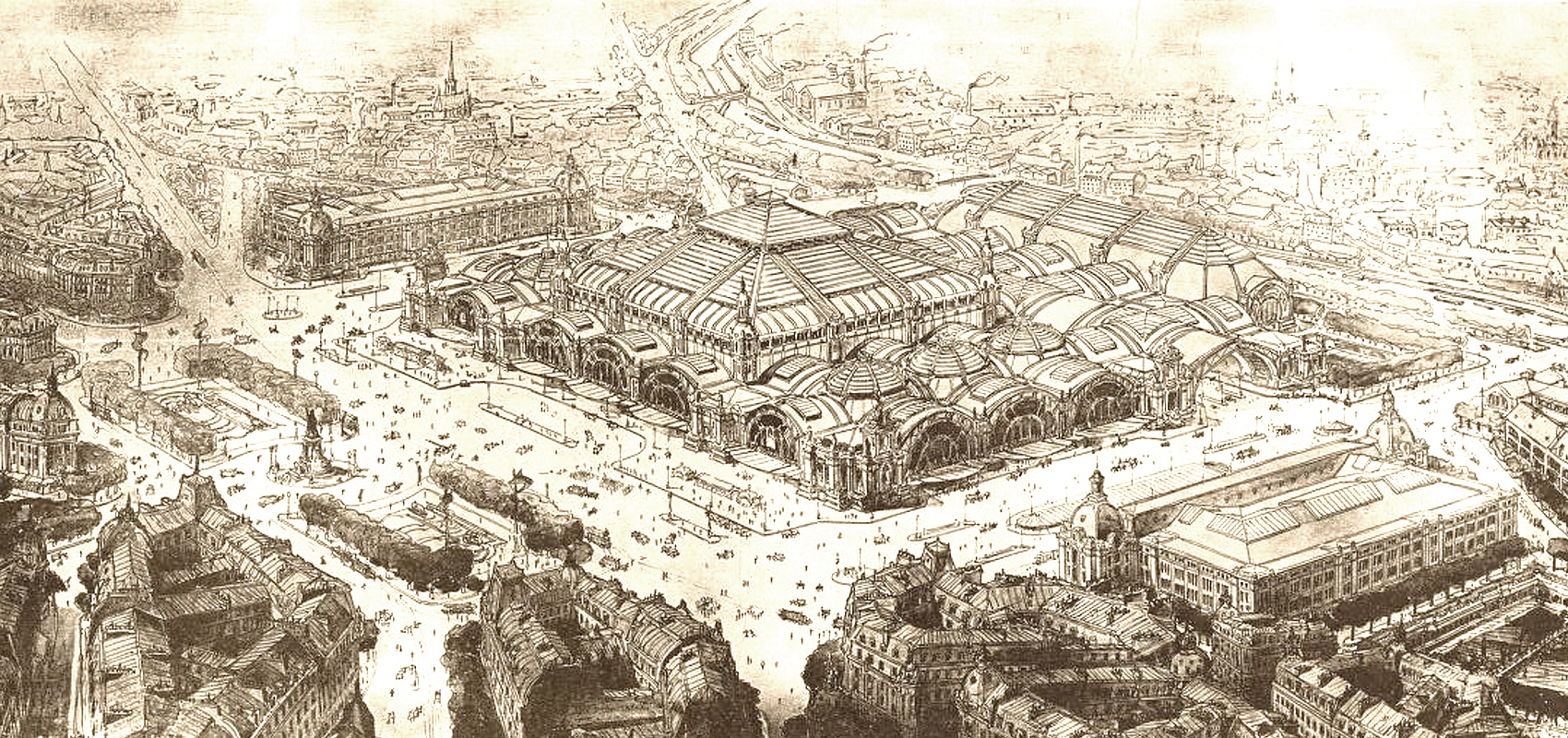

Place de la République train station

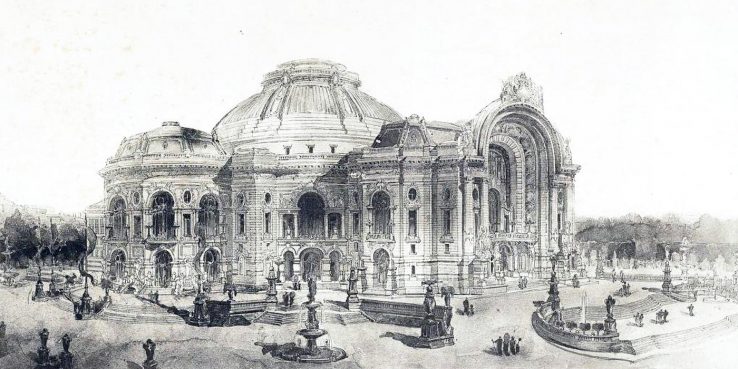

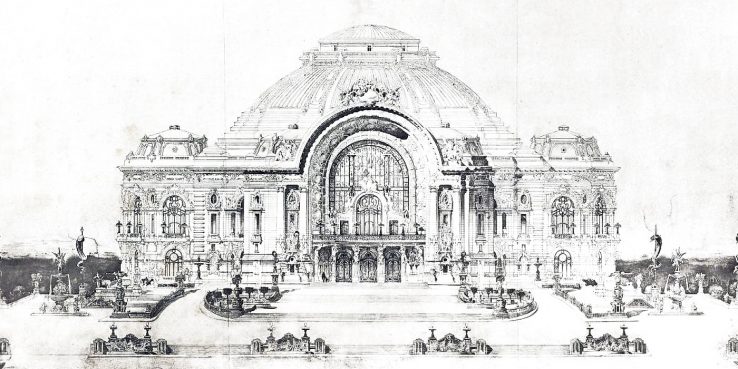

In 1909, Paul Bouchet won a National School of Fine Arts competition for the construction of a new train station in the center of Paris.

Bouchet proposed a huge Crystal Palace-like building that would sit between the Place de la République and the Canal Saint-Martin. A roofed passageway would separate the departure and arrival halls. The railway tracks would be underground.

Expanded Place de la République

Architect Claude Mortello had his own ambitious plan for the Place de la République that similarly involved tearing down half the neighborhood around it.

Concert halls

Eugène Chifflot and Maurice Prévôt both designed these various concert halls for Paris.

Unfortunately, that’s all the information I could find, which suggests these may have been doodles rather than serious plans.

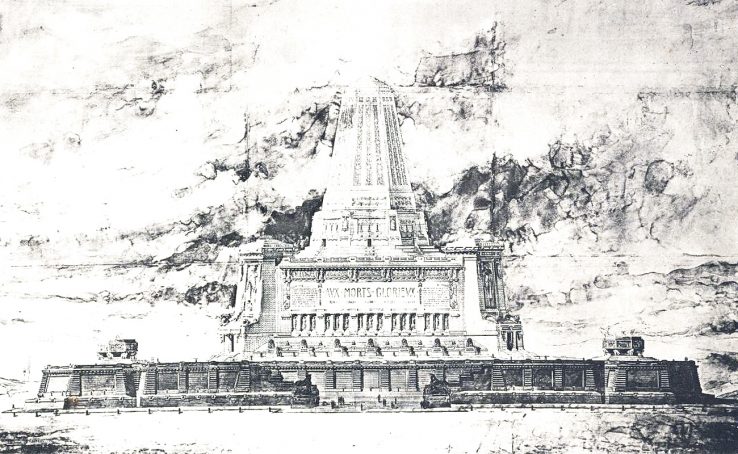

Monument to the Glorious Dead

Another one that sadly comes without specifics. All I know is that it was the brainchild of one Alphonse Gougeon.

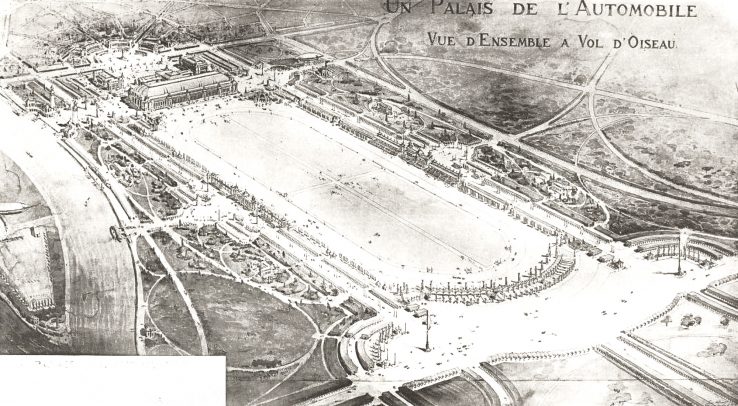

Automobile palace

Jean Hébrard designed this Automobile Palace as a student at the National School of Fine Arts. He moved to the United States in 1907, where he taught architecture at Cornell.

Hébrard served in the French army during World War I and returned to the United States in 1926, where he resumed teaching at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Michigan.

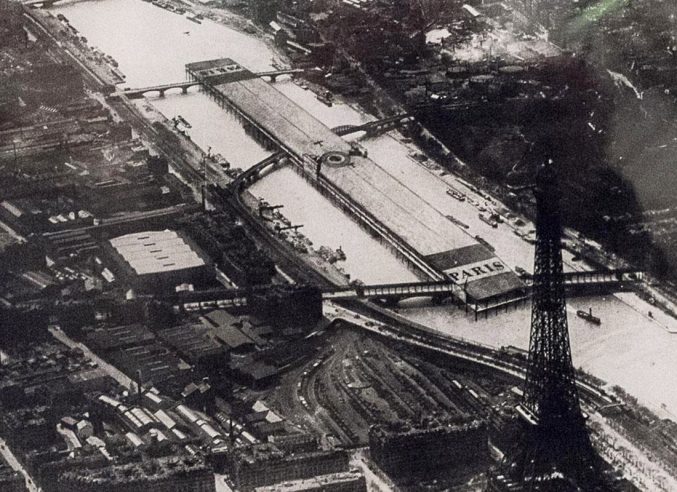

Airport on the Seine

In 1932, André Lurçat proposed building a mile-long runway on the River Seine. It would have consisted of two levels: one for landing and takeoff and a lower level to process passengers and baggage. Planes could be launched by catapult while brilliant beams of light would create an aerial corridor for nighttime landings.

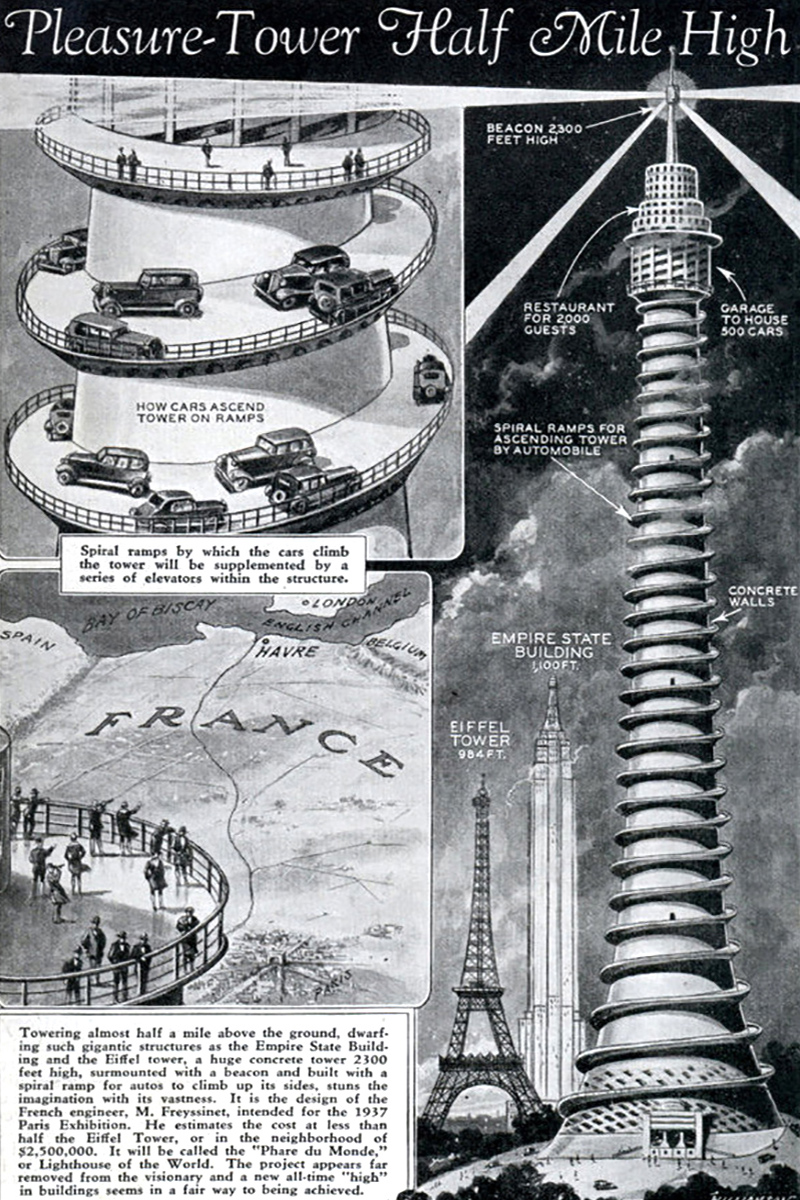

Phare du Monde

Eugène Freyssinet, a French civil engineer who specialized in the construction of bridges and airship hangars, proposed a gargantuan “Lighthouse of the World” for the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris.

Modern Mechanix reported in July 1933 that the 700-meter-high tower would have dwarfed the Empire State Building and the Eiffel tower and that its design, including “a spiral ramp for autos to climb up its sides, stuns the imagination with its vastness.”

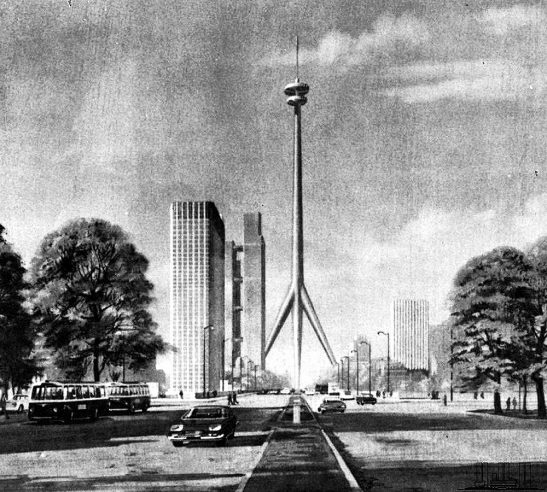

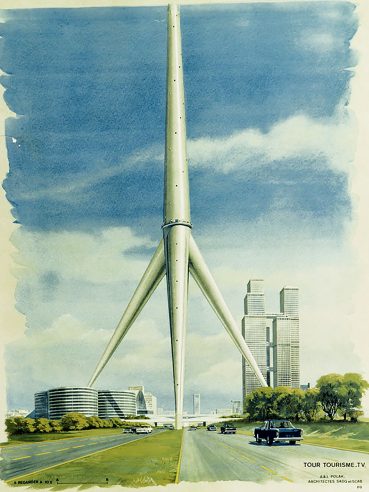

Polak Tower

In the early 1960s, the Belgian architects André and Jean Polak, who built the Atomium in Brussels, designed a 750-meter-high tourism and broadcasting tower for Paris that would occupied the spot where the Arch of La Défense now stands. It would have included a restaurant 600 meters up in the air with spectacular views of the city.

The tower was canceled for financial reasons and because the advent of satellites made tall broadcasting towers redundant.

La Défense cable car

In the late 1960s, Jean Pomagalski, an engineer and builder of ski lifts, suggested building a cable car, or téléphérique, along the northern circular boulevard of the then-new business district La Défense.

Aérotrain

A more serious proposal was to build a high-speed hovertrain connecting La Défense with the planned commuter town of Cergy. A contract for this Aérotrain was signed, however, resistance from the state-owned railway company SNCF, which preferred to use its own trains, and the projected cost of building the required elevated tracks convinced President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing to cancel the project in 1974.

I.M. Pei’s Grande Arche

Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei did not impress Parisians with his proposal for the Grande Arche of La Défense. A Danish couple was chosen instead to build this twentieth-century version of the Arc de Triomphe. Pei was commissioned by President François Mitterrand in the 1980s to renovate the Louvre, to which he added his distinctive glass and steel pyramid.

Jean Patou’s Les Halles

Victor Baltard’s glass-and-iron Les Halles market was demolished in the 1970s to make way for a large underground railway station and shopping mall.

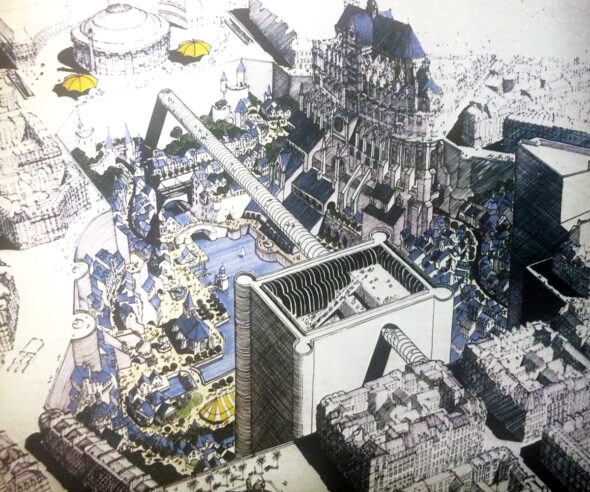

The International Union of Architects, headquartered in Paris, did not approve of the design and invited alternate submissions. They received more than 600, including one by Jean Patou of Lille, who proposed filling up the enormous open pit that had by then emerged at the foot of the Church of St Eustache with a pond and medieval-style buildings. A glass tube would have connected the historic Commodities Exchange with a tower on the site where the Châtelet-Les Halles train station was built.

April’s Extraordinary Paris

In the 2015 French-language animation film Avril et le Monde truqué, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 is averted when Emperor Napoleon III dies in an accident. In the following decades, top scientists, such as Albert Einstein and Enrico Fermi, mysteriously disappear, setting back the pace of progress. By the 1940s, the world has run out of coal and is burning wood instead to power its engines. The people of Paris have to wear masks outside to survive the smog. The French Empire is plotting a war against forest-rich Canada.

The rest of the plot involves a talking cat, a secret lizard city underneath Paris and the terraforming of the Moon, Mars and Venus.

Revoir Paris

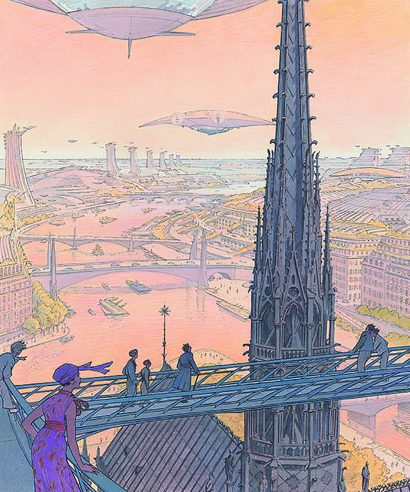

In François Schuiten’s and Benoît Peeters’ Revoir Paris (2014-16), a girl living on a space colony in the year 2156 dreams of a Paris that never was.

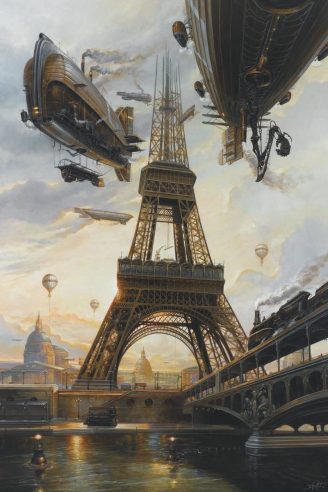

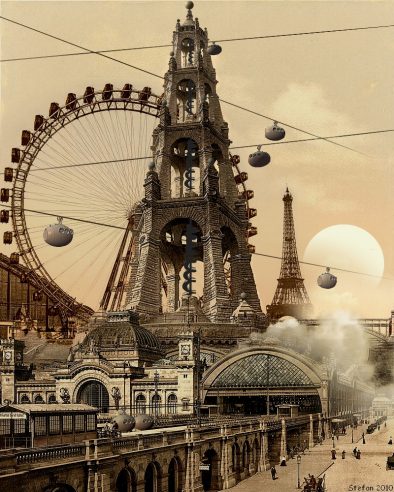

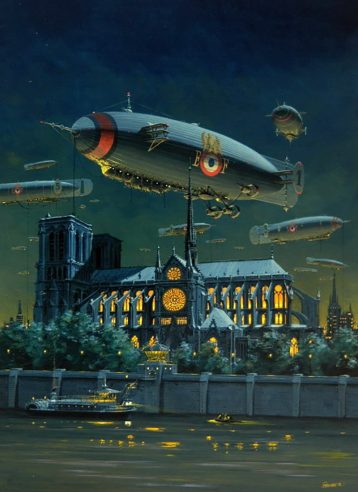

Steampunk Paris

Marcin Gęzikiewicz, Didier Graffet, Stefan Prohaczka, Ludovic Ribardiere, Gilles Roman, Sam van Olffen and “Manchu” have given us their own interpretations of a steampunk Paris.