Elevated railways, sky bridges, rooftop airports and a plan to drain the East River. New York City would have looked very different if these architects and engineers had had their way.

Arcade railway

This was essentially the first subway proposal for New York. In the 1860s, Egbert Ludovicus Viele, an engineer, came up with a plan for what he called an Arcade Underground Railway. It involved replacing the roads with railways and building another street level on top of it for carriages and pedestrians.

Owners of property along Broadway weren’t too happy about the proposal and it would take another forty years before New York got its subway.

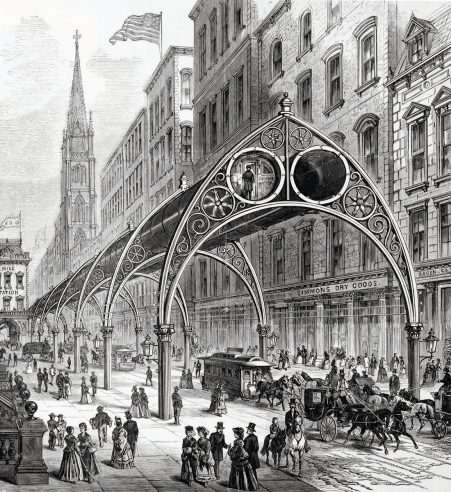

Pneumatic Elevated Railway

Even more steampunky was Henry Gilbert’s proposal for pneumatic railway tubes suspended from Gothic steel arches over New York City’s streets.

This was not a totally wild scheme. Gilbert had been the superintendent of the Central Railroad of New Jersey and obtained a patent for his elevated railway idea. He created a company but struggled to attract financing in the middle of the 1873 Wall Street Panic.

North River Bridge

The view of Manhattan from New Jersey would have looked quite different if Gustav Lindenthal had had his way. This Czech-born civil engineer called for an enormous, 1.8-kilometer bridge in 1887 that would have spanned the Hudson River.

The North River Bridge would have been sixty meters wide and sixty meters high to accommodate twelve railroads and 24 traffic lanes. It would have been twice the length of the George Washington Bridge, which connects Manhattan and New Jersey further up the Hudson River. The two supporting towers would have been bigger than the Woolworth Building, which was the world’s tallest skyscraper at the time.

The North River Bridge was never built, but Lindenthal did get to design a bridge on the other side of Manhattan: the Hell Gate Bridge, which connects Randalls and Wards Islands to Astoria in Queens.

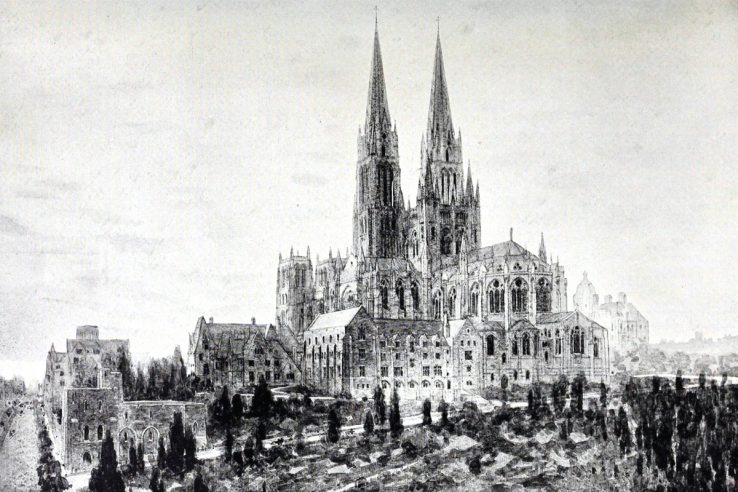

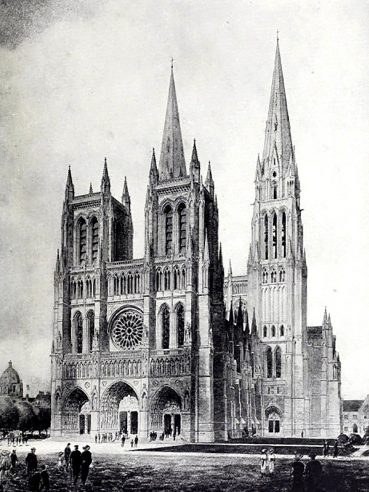

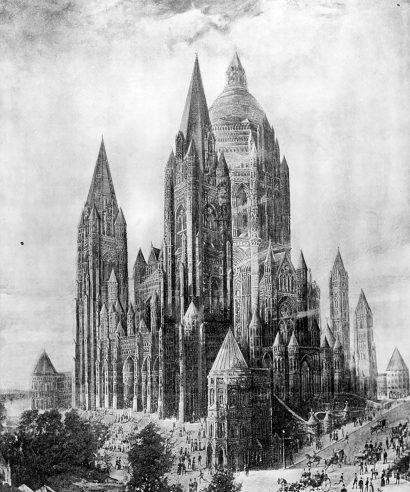

Cathedral of Saint John the Divine

Construction started on the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in 1892, but the building remains unfinished today. Hence its nickname: St John the Unfinished.

The cathedral was conceived as Byzantine-Romanesque, but after the death of Bishop Henry C. Potter, who had been the driving force behind it, the noted Gothic Revival architect Ralph Adams Cram was hired in 1908 to “Gothicize” the building. Cram’s design was clearly inspired by the Notre-Dame de Paris.

Other designs were submitted by Alexander Hay and William Halsey Wood. I’m not sure if Hay took part in the original 1888 competition, but Wood did. His design, a seemingly endless series of turrets, spires and arches surrounding an enormous domed tower, “drew both high praise for originality and criticism for impracticality,” writes Luis Rodriguez of the New York Historical Society.

Hotel Attraction

By 1908, Antoni Gaudí was already a well-established architect. He had designed various homes and public spaces in Barcelona in his unique, organic style and was about to commit himself entirely to the construction of his masterpiece, the Sagrada Família.

Before he did, though, Gaudí was commissioned by a group of New York businessmen to design a luxury hotel for the city.

Characteristically, Gaudí drew up plans for what would have been the tallest tower in New York at the time. Nothing came of his proposal. It’s unclear why. One story says the businessmen fell out with Gaudí over his left-wing political beliefs. Another says Gaudí fell ill.

Whatever the reason, Manhattan clearly missed out. The science-fiction series Fringe gives us a glimpse of what could have been. In its alternate-universe New York, Gaudí’s Hotel Attraction was built — and it looks amazing.

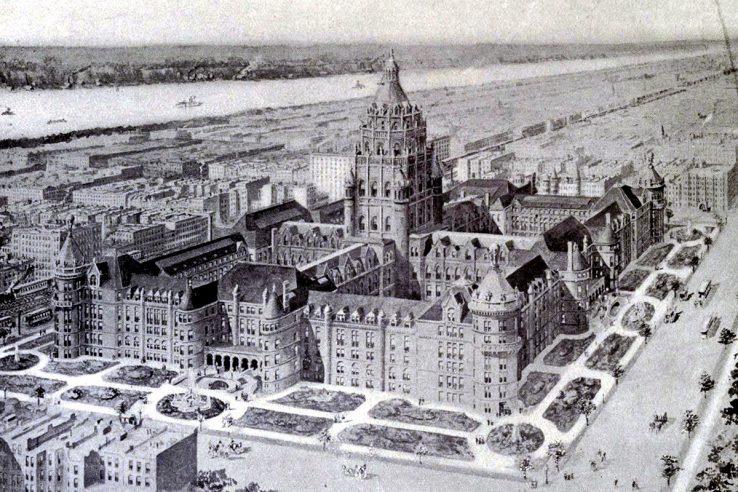

Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History is already one of the largest in the world, but its designers — Josiah Cady, Louis Berg and Milton See — had something even more monumental planned: a vast complex in Romanesque and Gothic Revival styles. Only the museum’s south range was built according to their design.

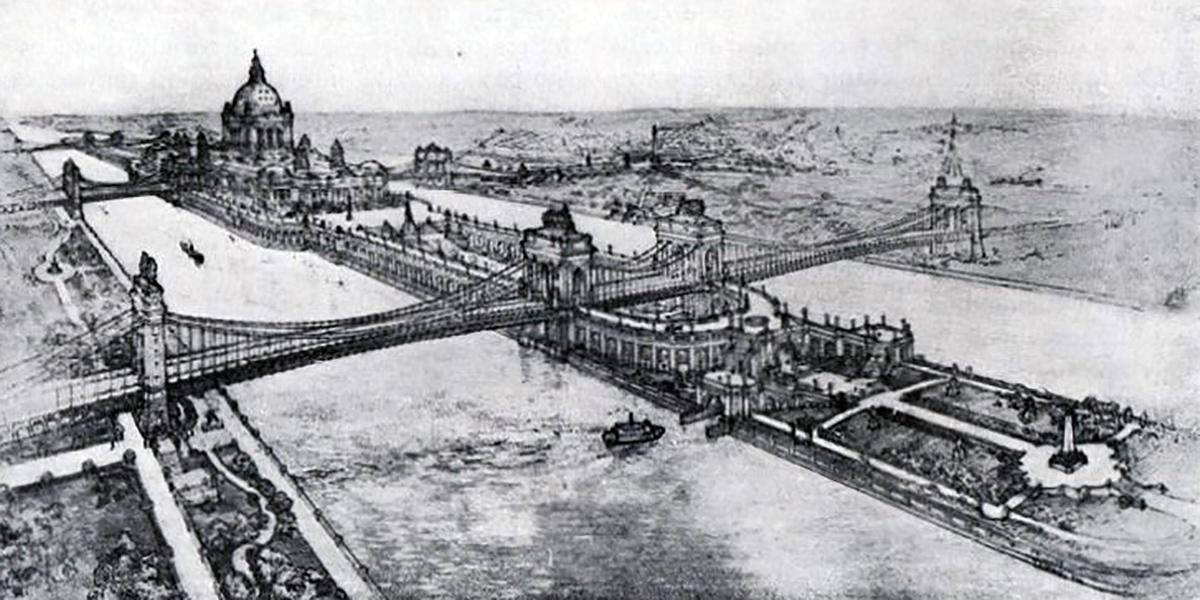

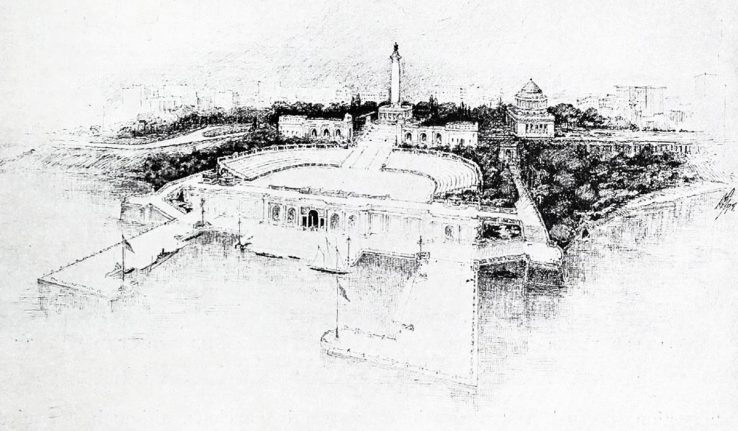

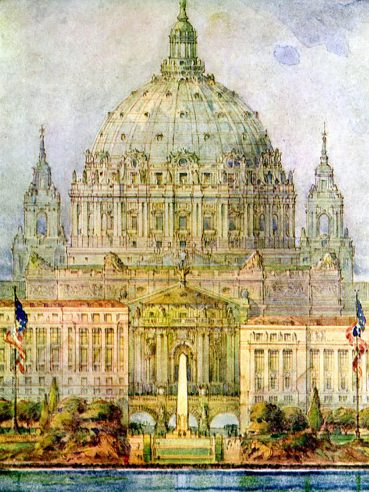

Civic Center on Blackwell’s Island

Around the turn of the last century, New Yorkers yearned for an Acropolis to crown their burgeoning metropolis. Former congressman John De Witt Warner lamented New York’s lack of “one or more great civic centers … effectively grouped … public or quasipublic structures that are, as it were, the vital organs upon which its vigor and character must so largely depend.”

Most of the planning centered around City Hall in Downtown Manhattan, but Thomas J. George, then a young architect, had a different idea: convert Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) into a new city center.

New York was expanding eastward, George argued, and Blackwell’s Island was closer to Midtown, the commercial heart of Manhattan. A Civic Center there would be truly central.

His scheme demanded the construction of two bridges, one of which would have passed right through the dome of the capitol, which bears a resemblance to the Administration Building Richard Morris Hunt had designed for the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893.

The Gotham Center for New York City History has more.

In 2019, the marketing agency iProspect created a digital rendering for Barratt London of what the Civic Center would look like today.

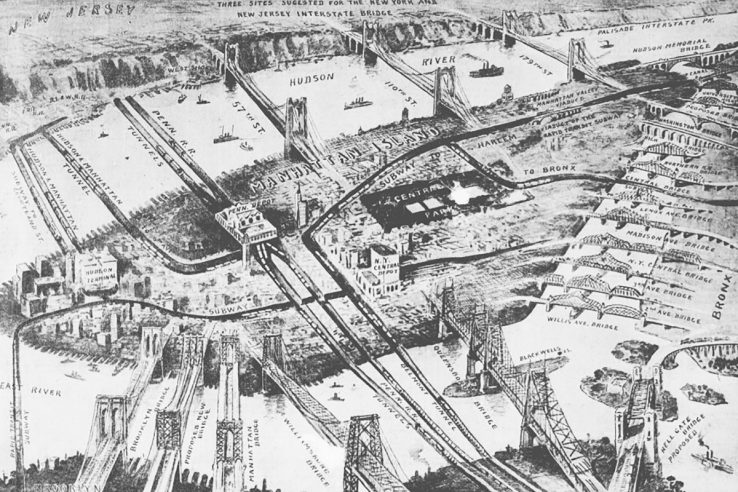

A few more bridges

New York Tribune published a map in January 1, 1911 that showed the various proposals for new bridges and tunnels around Manhattan.

Sandwiched between the existing Brooklyn Bridge and Manhattan Bridge was a new bridge named after “Long Pat” McCarren, the Democratic political boss of Brooklyn at the time. It came close to being built.

The Hell Gate railway bridge actually was built between 1912 and 1916. So was the Henry Hudson Bridge connecting the tip of Manhattan and the Bronx, although its construction was delayed until 1935 and plans for a highly ornamental concrete bridge were watered down a simpler, and cheaper, steel arch bridge.

The blog Stuff Nobody Cares About has more.

Future New York

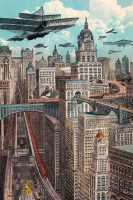

Many steampunks will be familiar with this picture. It’s a 1925 postcard that imagines the future of New York, but the original image is from 1911.

“The City of Skyscrapers” has elevated railways, both over its streets and between buildings, connected by huge (and probably hugely expensive) sky bridges. Airships fly overhead. All the towers are in the pleasant Renaissance and Gothic Revival styles of the early twentieth century.

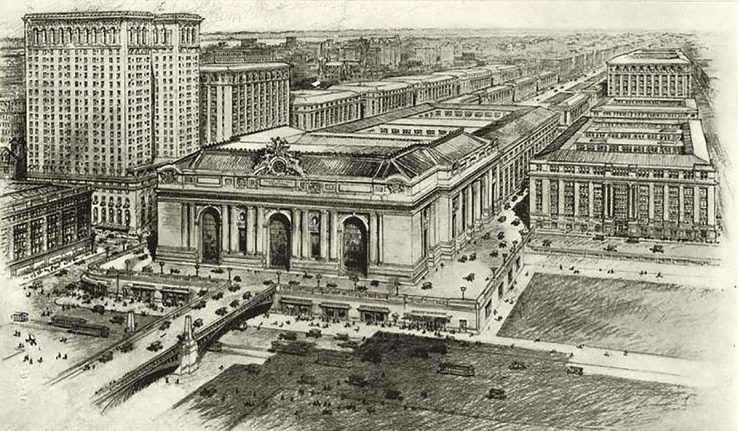

Grand Centrals that could have been

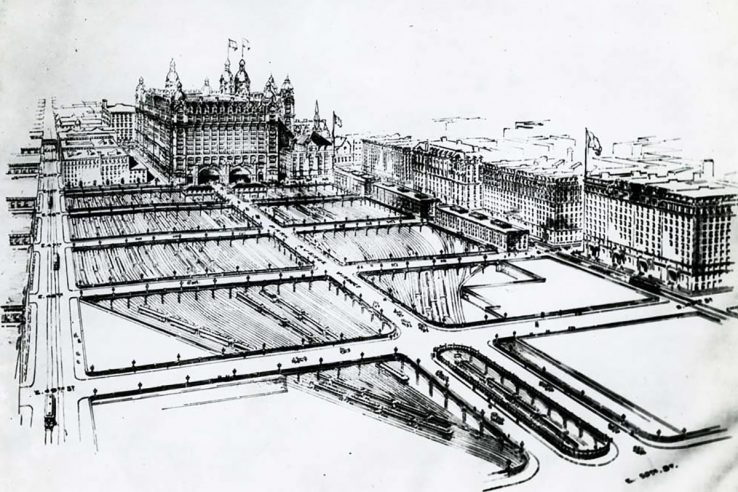

Between 1903 and 1913, New York’s Grand Central Station was torn down and replaced in phases by a Grand Central Terminal — still called “Grand Central Station” by most New Yorkers. Out of the many firms that vied to design the new railway station, two were selected: Reed & Stem of St Paul, Minnesota, who were responsible for the overall design, and Warren & Wetmore of New York, who were responsible for the building’s Beaux-Arts style.

Reed and Stem envisaged the new Grand Central as the heart of a “Terminal City” that would include new homes for the Metropolitan Opera and the National Academy of Design as well hotels and office buildings.

Other firms had different ideas.

McKim, Mead & White, who would later build the old Penn Station as well as the campus of Columbia University, proposed a sixty-story skyscraper, which would have been the tallest tower in the world at the time.

Samuel Huckle Jr. of Pennsylvania proposed a baroque turreted building.

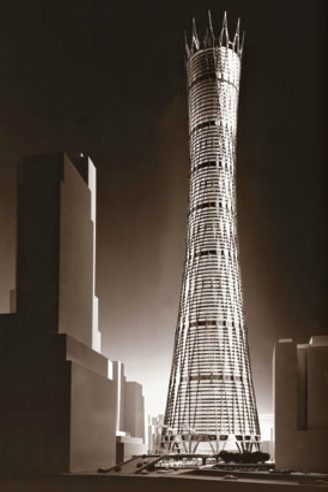

After the Second World War, Grand Central nearly fell victim to the same modernization craze that claimed Penn Station.

The first attempt to demolish the station came in 1956, when famed architect I.M Pei designed an eighty- to 102-story, hourglass-shaped tower known as the Hyperboloid. The railroad rejected it because it would have been too expensive to built.

By 1968, New York Central had merged with Pennsylvania Railroads to become Penn Central and they were looking for office space. Marcel Breuer designed a 55-story tower that would have stood above Grand Central. The terminal’s facade would have been preserved, but the entire main waiting room and part of the main concourse would have been demolished to make way for the skyscraper’s foundations.

Fortunately, the loss of Penn Station spurred New Yorkers into action. A Landmarks Preservation Commission was formed which designated Grand Central an historic landmark. Developers and the railroad appealed the decision all the way up to the Supreme Court, which finally ruled in the preservationists’ favor in 1978.

By then, the railroad had neglected maintenance and delayed repairs for two decades. It would take another decade for renovations to get underway and restore Grand Central to its former glory.

Grand Central’s official website has more.

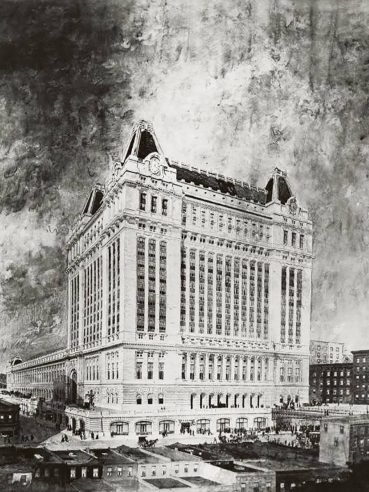

Manhattan Municipal Building

In the late nineteenth century, New York City Hall was running out of office space. Mayor Abram Hewitt appointed a commission to build a new Municipal Building, which organized four competitions between 1888 and 1907 for designs.

The winning entry was received from William Mitchell Kendall, a young partner at McKim, Mead & White. His proposal was a combination of Renaissance and Beaux-Arts influences.

Other firms that submitted proposals included Heins & LaFarge, founded by George Lewis Heins and Christopher Grant LaFarge; Hoppin & Koen, founded by Francis Laurens Vinton Hoppin and Terence A. Koen; and Howells & Stokes, founded by John Mead Howells and Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes. Henry Rutgers Marshall also submitted a design.

National American Indian Memorial

The National American Indian Memorial was a proposed monument to Native Americans on the site of Fort Tompkins in Staten Island, near the entrance to New York Harbor.

The project was the brainchild of Rodman Wanamaker, a department store magnate and patron of the arts. Congress set aside the federal land needed for the memorial in 1911, but neither it, nor any other government agency, was willing to provide funding. Wanamaker didn’t want to pay for the whole thing himself either and the project fizzled out during World War I.

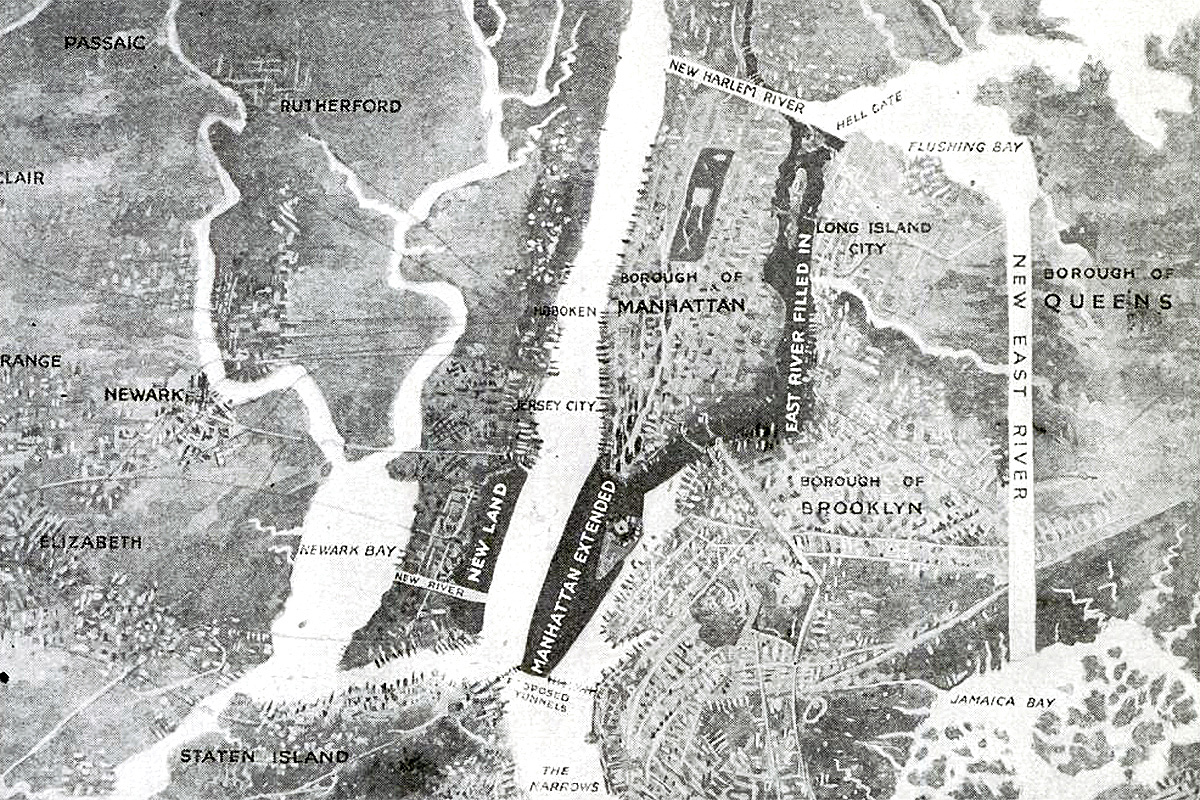

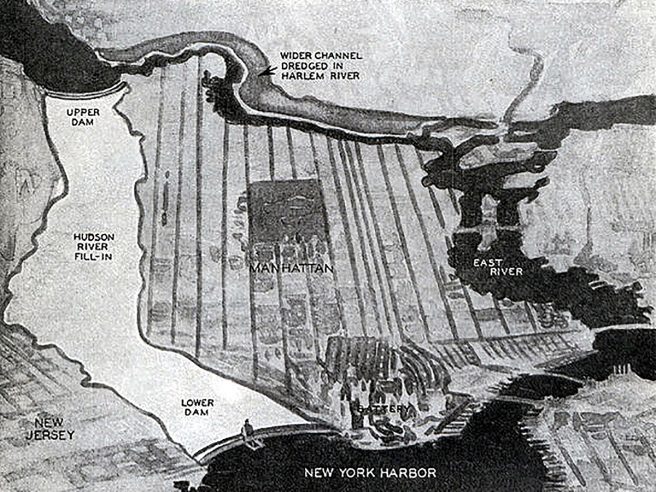

Proposals to drain the East River

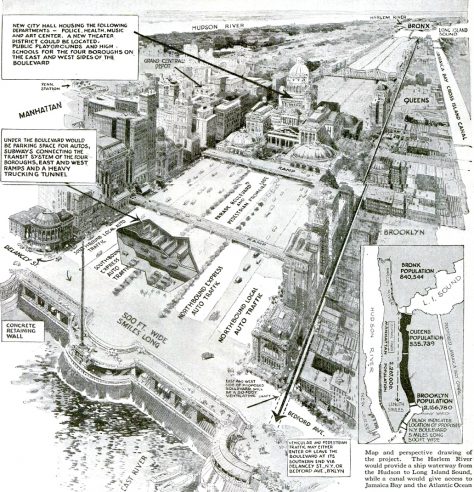

The first proposal to drain the East River came from T. Kennard Thomson, an engineer, in 1911. He suggested filling in the East River and extending Manhattan to the south. The Harlem River would be widened and a New East River dug east of Brooklyn to empty into Jamaica Bay. The Brooklyn Navy Yard, which would lose its access to the sea, was to be relocated to the mouth of New York Bay.

Thomson recognized that his plan would be expensive. But he also foresaw big rewards, writing in the January 1916 edition of Popular Science that the returns would “quickly pay off the debt incurred, and then would commence to swell the city’s money bags until New York would be the richest city in the world.”

Eight years later, John A. Harris, the deputy police commissioner of New York, similarly proposed draining the East River and transforming it into a transportation artery, including roads, subway lines and parking space, in order to relief congestion in Manhattan.

Harris envisaged the construction of two dams: one near the Williamsburg Bridge and one near Hell Gate. The riverbed would be “bridged with levels supported by steel uprights,” thereby connecting the boroughs of Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens, Popular Science reported that year. In the middle of the thoroughfare a new city hall could be built.

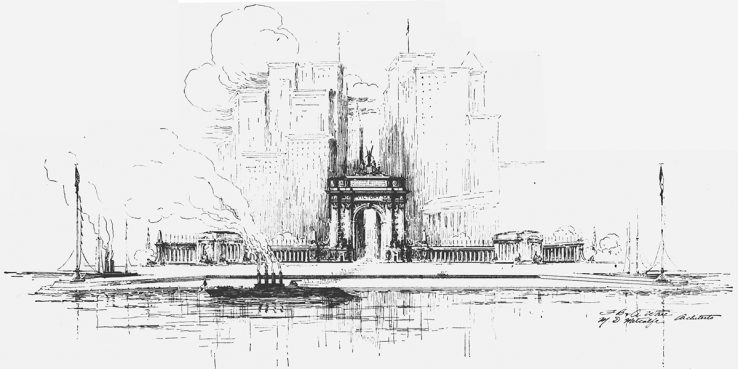

Victory Memorial

Immediately after the Great War, New York architects called for a monument to celebrate America’s victory.

The first proposal came from Donn Barber in 1918, who argued for integrating a sports stadium in a memorial site near Grant’s Tomb on Riverside Drive.

Otto Eggers and E.H. Rosengarten proposed a similar memorial about ten blocks down. It would double as a dignified harbor to welcome guests to the country.

The brothers Franklin and Arthur Ware and their partner, M.D. Metcalfe, similarly proposed a victory arch that would double as gateway to the city, but they more logically placed it in Battery Park at the southern tip of Manhattan.

Lighthouse

Did New York Harbor need a lighthouse? French architect Maurice Durand certainly thought so and proposed a structure that would surely have made an impression to those newly arriving in America.

Durand may have been biased, though. Designing lighthouses was his speciality. He built several on the Atlantic coast of his native France after the Second World War.

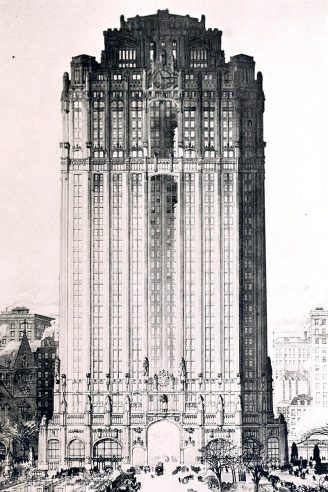

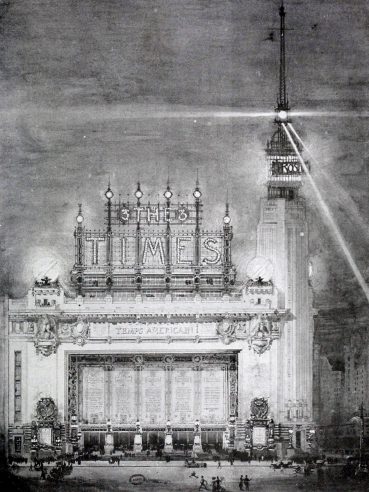

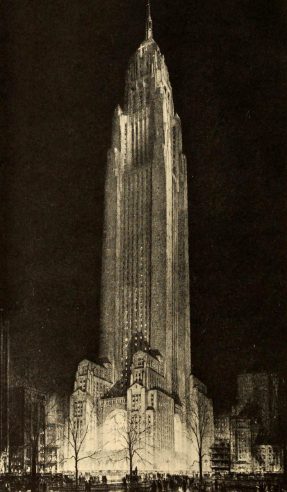

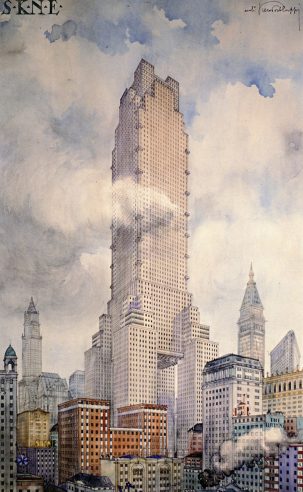

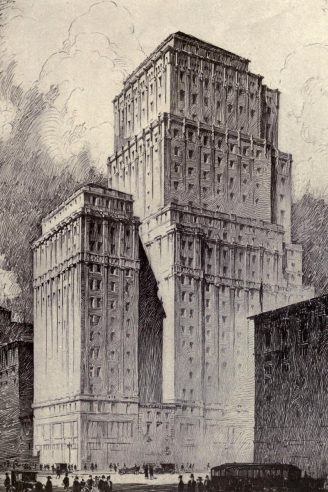

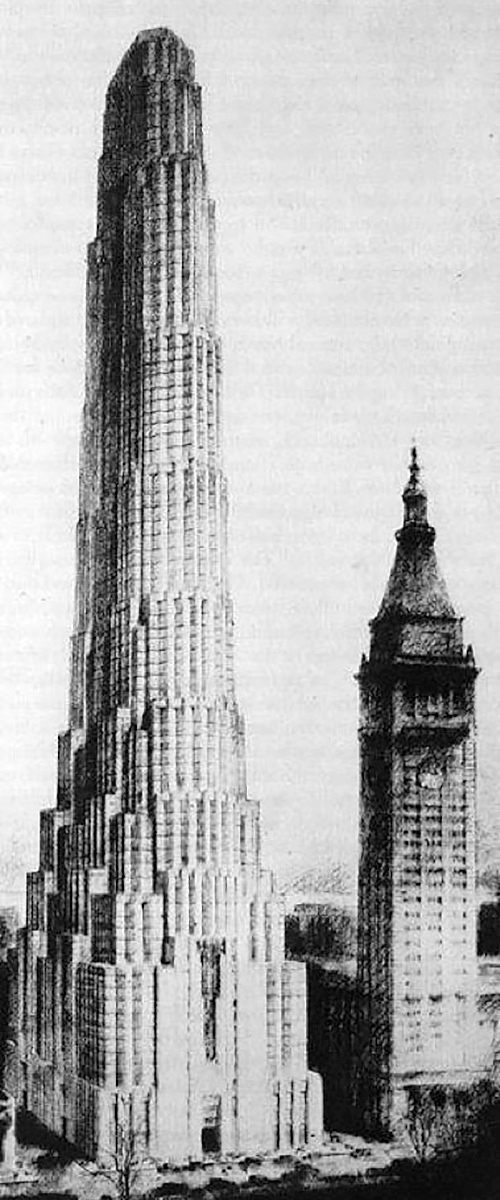

Unbuilt skyscrapers

Some of these look straight out of a Hugh Ferriss painting. The only thing they have in common is that none of them were built.

The first was a proposal for a newspaper office by a French architect called Boussois. (I haven’t been able to find his first name.) The Gothic Revival skyscraper was a study by Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, who moved to California where he would go on to define the Spanish Colonial Revival style. The tower with the impressive spire was designed by Clarence Howard Blackall, a Brooklyn-born and Paris-educated architect who designed many theaters in Boston. The S.K.N.E. tower was a study by Italian architect Piero Portaluppi. The bulky building on the right was Albert Buchman’s and Ely Jacques Kahn’s 1921 proposal for the New York headquarters of the Borden milk company.

Living on a bridge

This actually is a Hugh Ferriss painting, but the design was Raymond Hood’s.

The architect of 30 Rockefeller Plaza suggested that, to reduce congestion and create living space, fifty- to sixty-story apartment buildings could be added to New York’s bridges. There would be room for 50,000 residents on either side of this beast.

Le Corbusier in Central Park

This isn’t strictly an example of the “unbuilt” New York, since it was never a proposal. But it’s fun to imagine: what if Le Corbusier’s infamous 1925 Plan Voison for the demolition and reconstruction of Paris — named after its sponsor, aircraft and automobile builder Gabriel Voisin — were realized in Central Park instead?

Architizer has more.

Larkin Tower

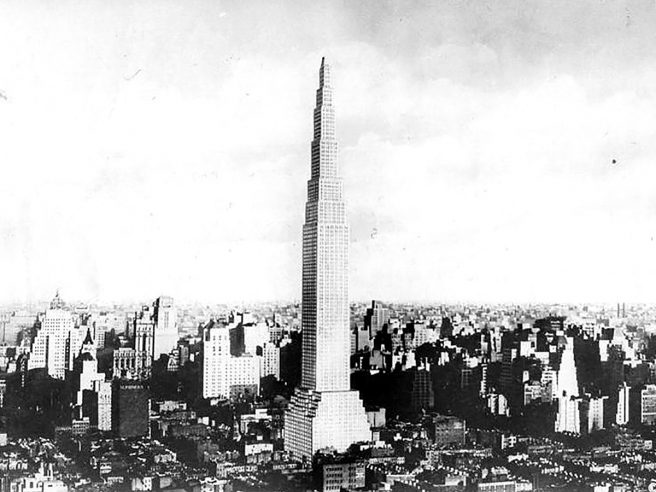

Businessman and self-styled architect John Larkin twice tried to built the tallest tower in the world.

His first attempt was in 1926, when he proposed a 110-story Larkin Tower for Midtown Manhattan, not far from Times Square. The tower would have been 370 meters high, pretty much the same height as the Empire State Building that was completed five years later. It was never built.

Larkin recycled his design in 1952, when he announced plans for a 600-meter high World Trade Building. This was unreal. Today there are only four buildings in the world that tall and they were all built in the last decade.

The New York Times has more.

Metropolitan Life Tower

By the 1920s, the headquarters of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (also known as MetLife) on Madison Avenue — known for its distinctive clock tower — was becoming too small. Architects Harvey Wiley Corbett and Dan Everett Waid were hired to design a new building, which would sit on the same bloc.

Their proposed 100-story tower would have been the tallest in the world at the time, but the 1929 crash intervened. Only the base of what was called the North Building was constructed, between 1932 and 1950, thirty stories high.

Opera House

In the late 1920s, the Metropolitan Opera was looking for a new home. Benjamin Wistar Morris developed a plan for a new opera house on a stretch of Midtown owned by Columbia University, however, the Met could not afford it. John D. Rockefeller Jr., the son of the oil magnate, was willing to help pay for the new building. Columbia leased the plot to Rockefeller for 87 years at a cost of $3 million per year.

Then the stock market crashed and the Met had to abandon its quest for a new opera house altogether. Rockefeller went ahead with the construction of what became Rockefeller Center.

Chrystie-Forsyth Parkway

New York City acquired the land between Chrystie and Forsythe Streets in 1929 with the intention of demolishing the tenements that littered the area. The Regional Plan Association, a group of bankers, developers, railroad men and philanthropists, suggested replacing the houses with a grand avenue: the Chrystie-Forsyth Parkway. Their design maximized air and light by incorporating low-rise buildings, parks and adequate spaces between Art Deco skyscrapers.

Nothing came of the proposal. Instead, a park was built, named after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s mother, Sara.

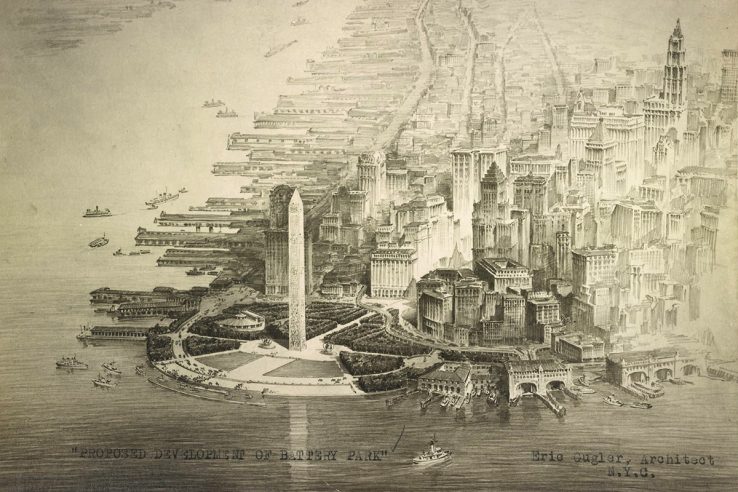

Obelisk at Battery Park

As late as 1929, there were still plans for a World War I memorial. Eric Gugler, who would go on to design Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Oval Office, proposed this 180-meter obelisk at Battery Park. Similar to the Washington Monument, but — this is New York, after all — 75 meters taller.

Civic Center

I’m not sure if this was a serious proposal or Chester B. Price’s imagination running wild. There is little information about this architect and illustrator online. The New York Times ran a short obituary in 1962. The Smithsonian American Art Museum has a small collection of his work online.

In any event, his tower would have overshadowed both the old City Hall and the new Manhattan Municipal Building (of which we saw alternative designs earlier).

New York in 2031

In September 1931, Science and Mechanics featured on its cover a vision of New York in a hundred years drawn by Frank Rudolph Paul.

The Empire State, the tallest building in the world at the time, is dwarfed by colossal buildings twice its size. An even larger structure looms in the background with statutes that themselves are the size of skyscraper.

Future Tower City

Edwin Maxwell Fry didn’t look quite that far ahead. The British architect, who would go on to design many buildings in colonial Africa, was hired by the aforementioned Regional Plan Association to design a “Future Tower City” in 1931.

Much like their failed Chrystie-Forsyth Parkway, the association’s rationale in this case was to clear Manhattan of slum and working-class areas that they claimed outraged “one’s sense of order.”

Sunnyside Yards Terminal

Also in 1931, the same Regional Plan Association proposed building an office and terminal building on top of the Sunnyside Yard in Queens — which is still an eyesore.

The tower, designed by Arthur C. Holden & Associates, “would dominate all this part of the Borough of Queens,” the association wrote.

You can find out more at the RPA’s blog.

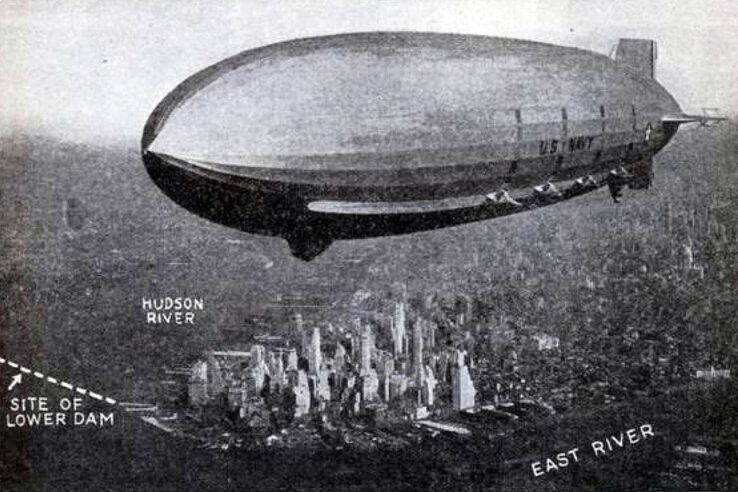

Filling in the Hudson River

Norman Sper was a publicist and engineering scholar who proposed damming the Hudson River on the north and south sides of Manhattan to create around ten square miles of new land.

Modern Mechanix reported in March 1934 that the plan would have involved widening the Harlem River in order to allow for sufficient drainage into the East River.

Sper estimated his project would cost around $1 billion to execute, or $19 billion in today’s money. But the potential profits were enormous:

An annual income of a hundred million dollars a year would represent a return of ten percent on the investment of a billion dollars and engineering experts all agree that this would be only a trifle of the amount that could be realized from this great project.

Several engineers consulted by Modern Mechanix agreed, but this was 1934 — the height of the Depression. It’s not hard to understand why this reclamation project never happened.

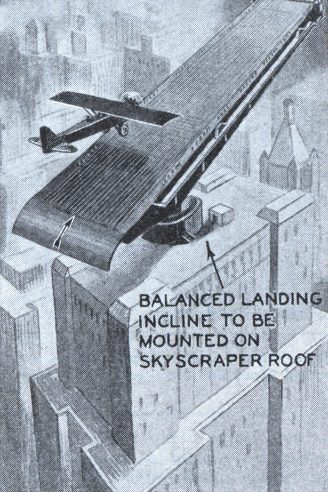

Rooftop airports

Modern Mechanics reported in February 1930 that one New Yorker had come up with a particularly novel way to make the city easier to reach by aeroplane. He proposed to put turntable runways on top of skyscrapers:

The device is declared to offer many advantages over the proposed platforms for such landings. The landing table can be tilted at any angle and swung about in any direction so that the wind is along its axis. The incline naturally serves as a brake on the landing ship and air blasts assist in checking the speed of the landed ship. The turntable would also present an incline which would enable a faster than ordinary take off.

I know the taxi ride from JFK to the city can be a drag, but I’d still take that over risking my life with one of these contraptions. Who was the brilliant/maniac New Yorker who came up with this?

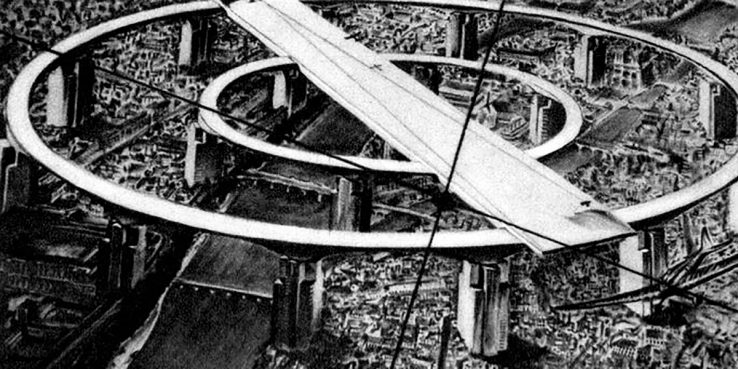

Turns out it can always get worse.

From the same magazine — Modern Mechanix — comes this idea by “a French engineer”:

Proposed as a solution to the problem of locating an airport in the heart of any big city, a design for a long orientable runway, which would be mounted on circular tracks atop tall buildings.

What could possibly go wrong?

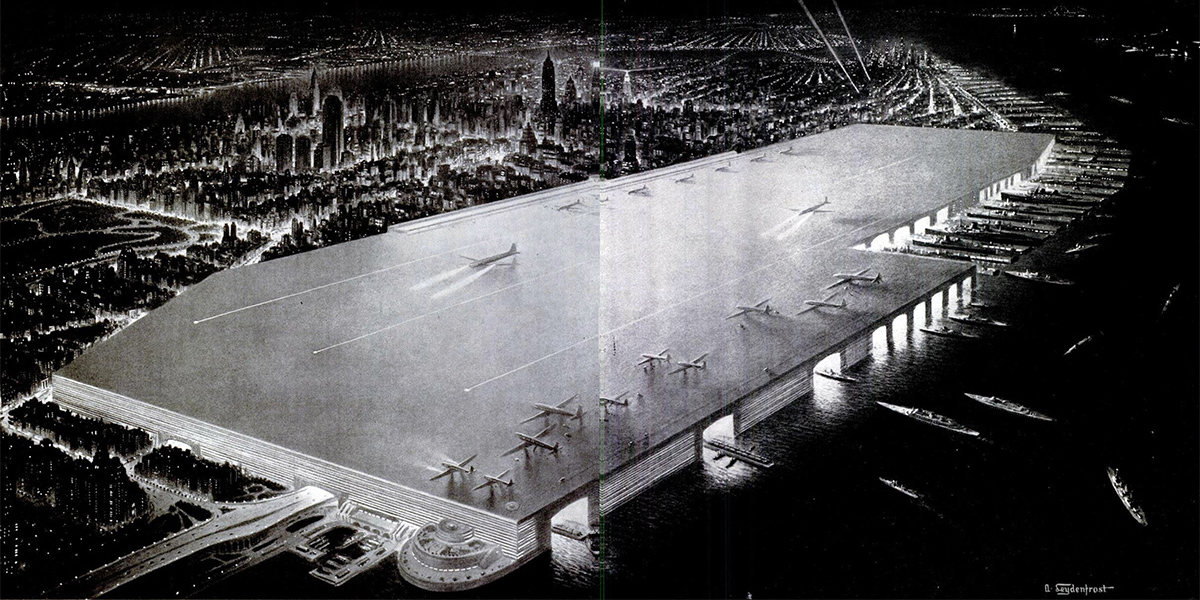

Nightmare airport

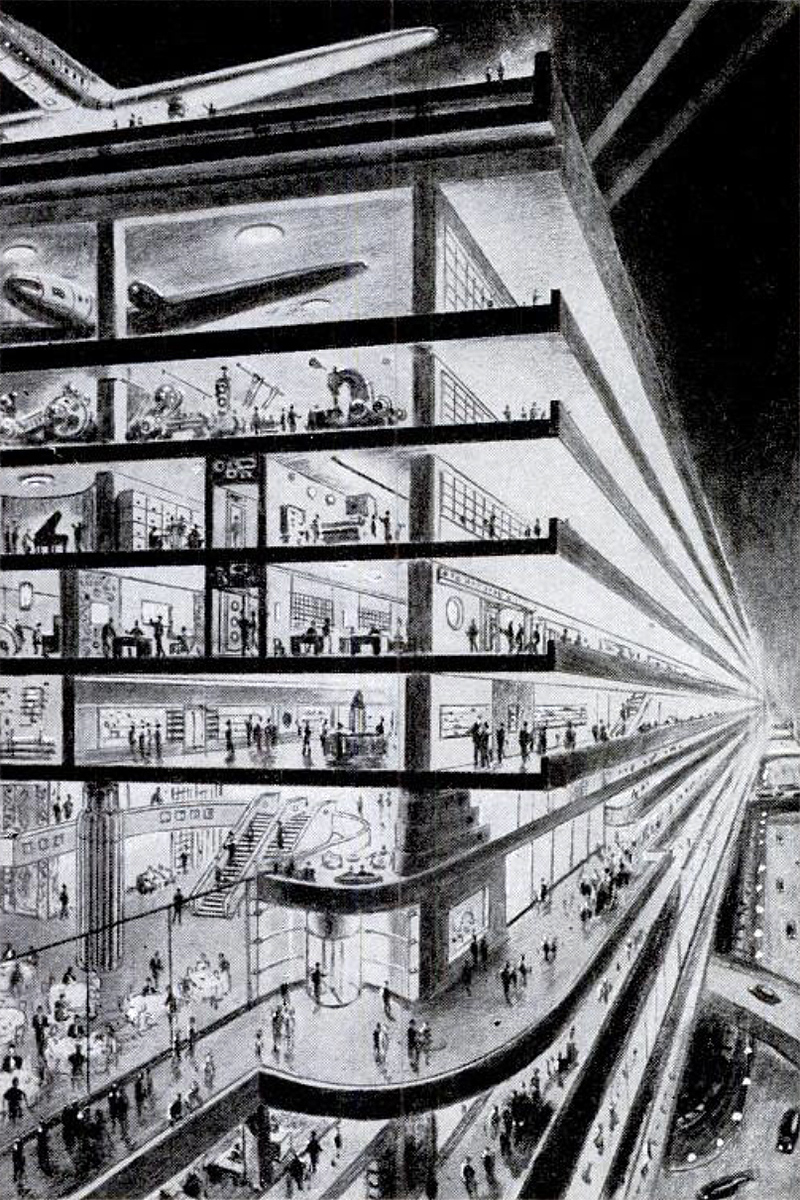

This may have seemed like a good idea pre-9/11, but the idea of building a huge airport in Manhattan would surely be laughed out of the room today.

I’m not sure if it was more realistic half a century ago, but this is what Life magazine published in March 1946: A “dream” airport for New York on the Hudson River shore.

It is an airport built 200 feet above street level right over 144 square blocks of Manhattan’s crowded, valuable West Side from 24th to 71st Streets and from Ninth Avenue to the river.

The top would be roughly the size of Central Park and accommodate three parallel runways.

Under the landing platform would be ten stories of apartments and office space, topped by a vast hangar deck with a 50-foot ceiling clearance.

Further down, traffic would be tunneled through the network of buildings while ships could dock right under the terminal.

The idea came from William Zeckendorf, a New York real-estate mogul. He estimated that building this monstrosity would cost around $3 billion, or nearly $40 billion in today’s money. He also figured it would take 55 years to recoup the investment.

Life predicted increased air travel would make Zeckendorf’s idea “a necessity”. Thankfully, they were wrong about that.

In 2019, the marketing agency iProspect created a digital rendering for Barratt London of what this airport might look like in today’s Manhattan.

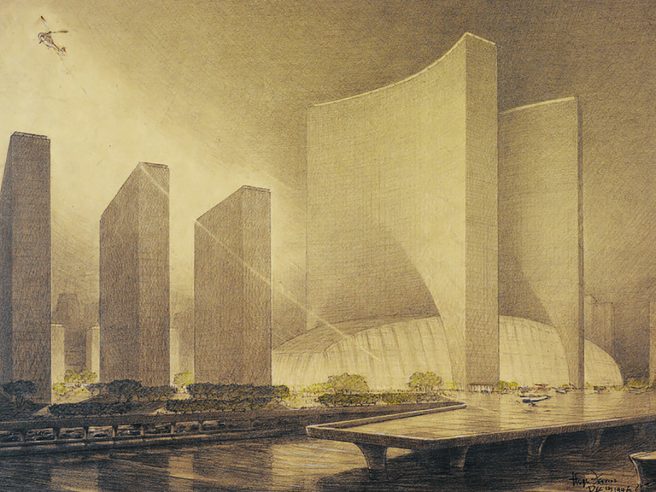

X-City

An airport on the Hudson River wasn’t Zeckendorf’s only pet project. Where John D. Rockefeller Jr. had his Rockefeller Center, Zeckendorf would have X-City, a modernist building complex on Manhattan’s eastern waterfront. It was to have apartment and office buildings, a marina, a new home for the Metropolitan Opera and — of course — a rooftop airport.

Zeckendorf didn’t have the money to make it happen, though. In 1946, he sold the land to the Rockefeller family, who donated it to the United Nations.

Untapped Cities has more.

Brooklyn Battery Bridge

The Brooklyn Battery Bridge was one of the first controversial projects of New York’s all-powerful building master Robert Moses.

In the late 1930s, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia sought to alleviate congestion in the city. The original plan was to build a tunnel between Brooklyn and Manhattan. Moses preferred a bridge.

Locals objected. A bridge would have ruined Battery Park and obstructed the view of the Manhattan skyline. Property owners on either side of the water feared it would depress the value of their real estate. Eventually it took the intervention of federal authorities to stop Moses.

The New York Preservation Archive Project has more.

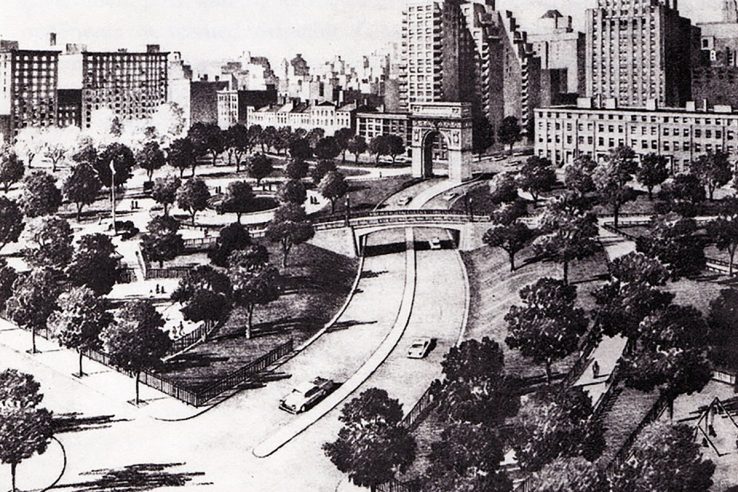

Avenue through Washington Square Park

Moses’ next defeat came in Greenwich Village. Now a charming neighborhood, in the 1950s it was pretty desolate. Moses’ plan to clean it up was to extend Fifth Avenue straight through Washington Square Park. The argument was that it would improve the flow of traffic and provide access to his planned Lower Manhattan Expressway.

Community resistance, led by activist Jane Jacobs and former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, defeated the plan.

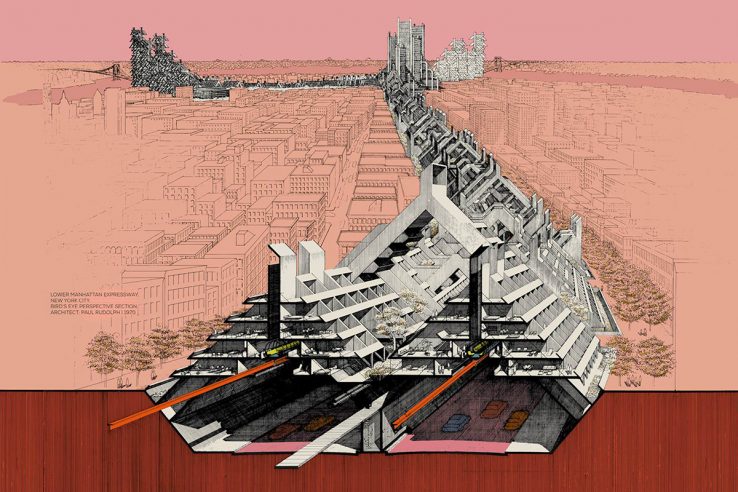

Paul Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway

The whole Lower Manhattan Expressway project — a proposal for an elevated, ten-lane highway through the middle of Lower Manhattan — was hugely controversial. The city ultimately abandoned it in 1968 after years of protest.

A year earlier, the Ford Foundation had employed the Brutalist architect Paul Rudolph to breathe new life into it.

Rudolph went way beyond the original plan. He sank the expressway into the ground and added enormous towers and monorails on top of it. The old city would have completely disappeared under vast pyramid-shaped, glass-and-concrete monstrosities.

Learn more about the history of the Lower Manhattan Expressway from The New Yorker and Curbed.

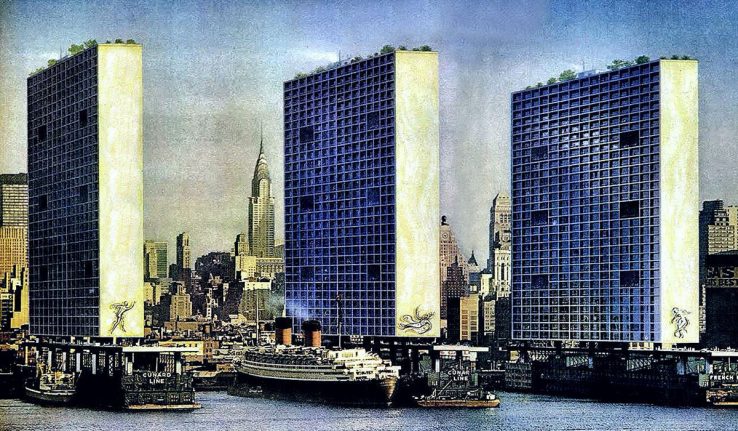

Towers on the Hudson River Piers

Life magazine reported in November 1962 that Governor Nelson Rockefeller had proposed a dramatic plan for constructing skyscraper apartment buildings on tax-exempt real estate. These would rise in so-called “air space” above publicly owned highways, schools, subway yards and — as shown in the picture — piers.

The plan was for middle-income families, earning between $5,000 and $10,000 per year — too much to qualify for public housing but too little to afford private rent in Manhattan — to populate these riverfront apartments.

ABC Tower

Bertrand Goldberg’s proposed headquarters and transmission tower for ABC television would have graced the New York skyline at 400 meters, making it the tallest building in the city at the time (1963).

The main building, 175 meters high, was a complex circular structure of concrete and glass which resembled a set of bundled tubes. The various clusters were organized around a communal space in the center for joint enterprises. The transmission antenna would have stood next to it.

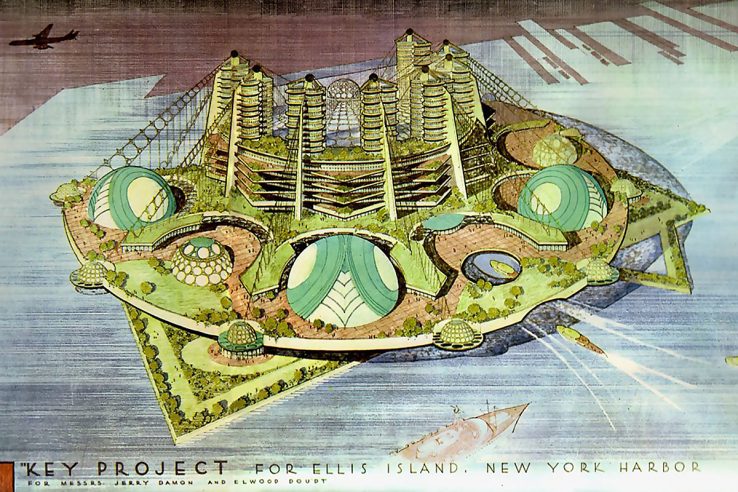

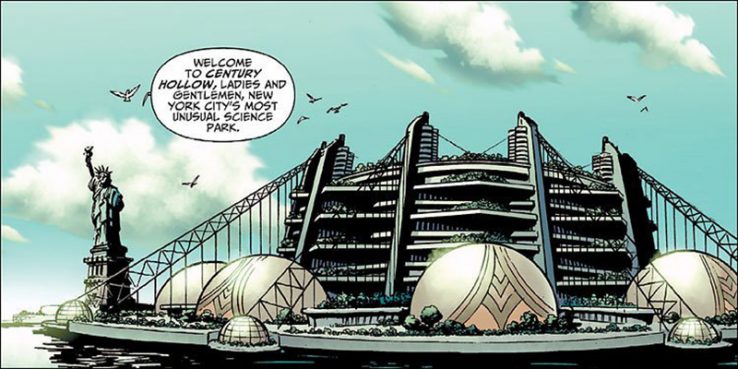

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ellis Island

After the immigration center on Ellis Island was decommissioned in 1954, the site was offered to developers. The winning bid proposed to build a “completely self-sustained city of the future,” designed by the recently deceased Frank Lloyd Wright. It consisted of thousands of apartments and huge, air-conditioned domes with hospitals, schools and theaters.

The scheme was rejected, but it featured in Grant Morrison’s Manhattan Guardian comic 2005.

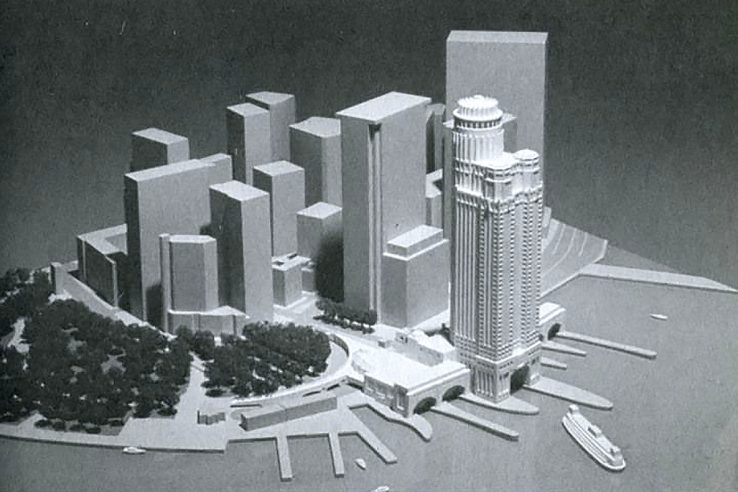

Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe’s Battery Park Apartments

You don’t have to be a fan of Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe’s work to see that his proposal might have been an improvement over the bland, grey- and pastel-colored towers that were built on the southeastern tip of Manhattan instead.

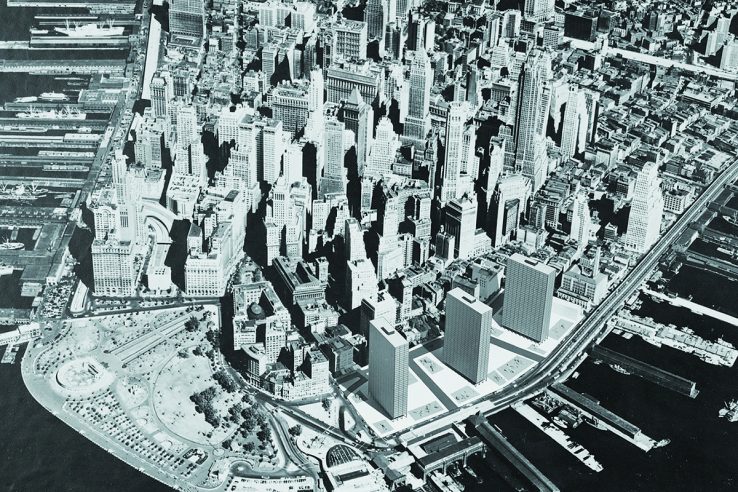

World Trade Center

One of the early proposals for the World Trade Center, published in June 1960, was for an exhibition hall and 50- to 70-story building on the site of the South Street Seaport, which had seen a continuous decline in business for decades.

Ultimately, a site on the other side of Manhattan was chosen: Radio Row, a neighborhood in the Lower West Side that was also in need of a revitalization.

Victor Gruen’s Welfare Island

Victor Gruen, an Austrian-born architect known for his urban revitalization proposals which had inspired the master plans for Fort Worth, Texas and Kalamazoo, Michigan, was commissioned in 1961 to come up with a plan to breathe new life into what was then known as “Welfare Island” due to the presence of many alms houses, hospitals and even a lunatic asylum.

Gruen would have paved over the entire island and erected multiple tower buildings to house up to 70,000 New Yorkers. There would have been pools, tennis courts, shops and schools. Mayor Robert F. Wagner was impressed, but others thought the proposal monstrous.

Under Wagner’s successor, John Lindsay, the city opted for a more modest plan by Philip Johnson and John Burgee. It introduced more green spaces, better transit access and just 5,000 additional apartments.

South Ferry Plaza

In 1987, the firms Fox & Fowle Architects and Leslie E. Robertson Associates proposed building a skyscraper on top of the South Ferry terminal in Lower Manhattan. The building, 330 meters high, would have been topped off by a glass dome with an observation deck and restaurants that lit up at night, hence the project’s nickname, “A Lighthouse at the Tip of the Island.”

Dieselpunk tower

This design by Mark Foster Gage Architects would have put a 102-story dieselpunk tower in the heart of Manhattan’s so-called Billionaires’ Row: a set of luxury skyscrapers along the southern end of Central Park.

6sqft reports the whimsical design is a “habitable sculpture of sorts, adorned from top to bottom in ornaments ranging from gears and propellers to an abstracted pair of birds diving in for a landing on two wing-supported balconies.” At the top would be a temple-like observational platform, crowned by a golden wreath.

Sadly, nothing came of the project.

5 Comments

Add YoursFascinating! I’ve been perusing this article and its links for days, and I’m still not finished. I once again wonder why the roads not taken seem more interesting!

I’m glad you enjoyed it! It took me a few months to collect all of this.

I guess partly it’s our fascination with the what-might-have-been and partly because some ideas were never realized because they were overly ambitious or impractical?

I love these “what if” designs and scenarios.

Readers of this article might be interested to see the latest in an irregular series in the UK’s ‘The Guardian’ newspaper about unbuilt constructions in cities. This one features Bristol, a port city in South-West England. In my view, the bridge proposed in 1793 and the tram terminus that won a competition in 1895 but was never built, are the best:

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2019/mar/12/weirs-and-aerial-walkways-the-bristol-that-might-have-been

That William Bridges bridge looks amazing!