In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Canada’s railway companies built grand hotels along the routes of the country’s burgeoning rail network. Many of these hotels were built in French château- and Scottish baronial-inspired styles, rich in dormers, towers and turrets.

When air travel started to compete with the railways in the second half of the twentieth century, many of the hotels struggled. Some were closed and torn down. The ones that survived are now national landmarks.

Let us take you on a tour of the grandest of Canada’s railway hotels.

Windsor Hotel, Montreal

The first of the grand railway hotels, the Windsor, embodied the commercial success of Montreal, then Canada’s largest city.

It took a few years for the hotel to become successful, but by the turn of the century it had become the center of Montreal’s elite social life. A fire in 1906 provided the impetus for an expansion, doubling the number of rooms. During their royal tour of Canada in 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth stayed at the Windsor.

Another fire destroyed a third of the hotel in 1957. The damage was so extensive this time that the original building had to be torn down entirely. The Windsor continued to operate out of the North Annex, built in 1906, but the hotel fell into decline. It closed in 1981. The North Annex is now an office building.

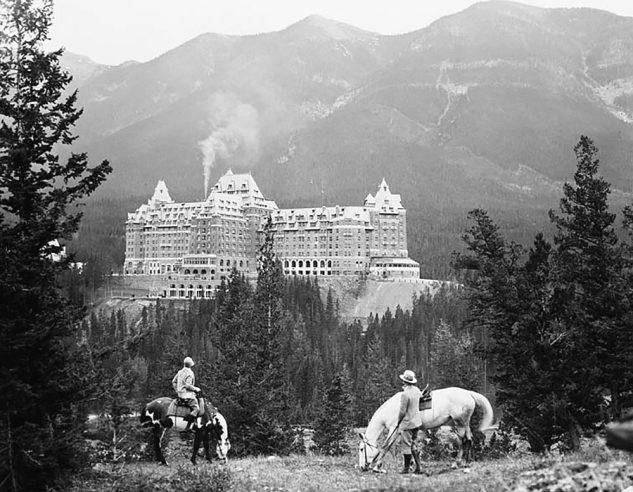

Banff Springs Hotel, Alberta

Located in the Banff National Park of Alberta, the Banff Springs Hotel has gone through several iterations.

The original hotel, which opened in 1888, was an Alpine structure adorned with stone accents, dormers and turrets. But it had accidentally been built the wrong way around, with its back to the mountain vista. Expansions were made in 1902. Only four years later, plans were drawn up for a complete overhaul. Walter Painter, the architect, designed an eleven-story tower in concrete and stone, flanked by two wings, this time facing in the right direction. For a time, the so-called Painter Tower was the tallest building in the country.

World War I delayed the completion of Painter’s plan. It wasn’t until after a fire in 1926 had destroyed what was left of the original hotel that his two wings were finally completed.

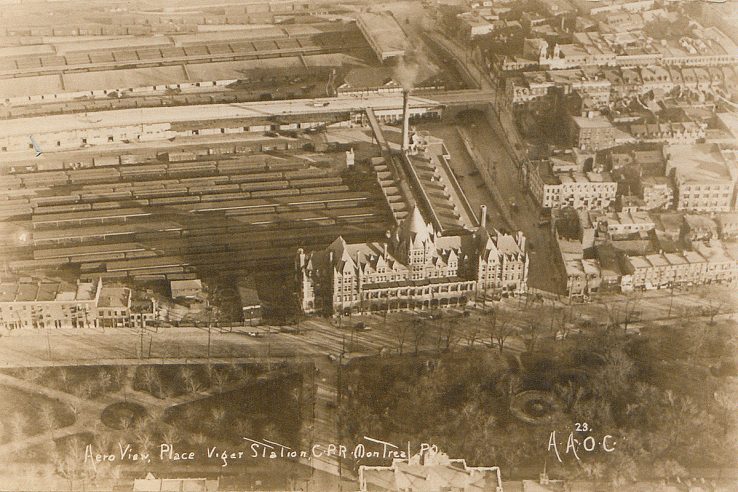

Place Viger, Montreal

Killing two birds with one stone, the Place Viger in Montreal served as both a railway station and a grand hotel. Built in the Châteauesque style, inspired by French Renaissance architecture, it opened its doors in 1898.

The Viger competed with the Windsor Hotel. The first was favored by French-speaking elites, the second catered to Anglophones.

When the city’s commercial center shifted northwest in the beginning of the twentieth century, the hotel lost its appeal. The Depression forced it out of business in 1935. The railway station continued to operate until 1951. The building was then converted into office space. A highway was built next to it in the 1970s, straight through the historical heart of the city, making the whole area undesirable.

In recent years, the Viger and its surroundings have seen a revival. The building is now home to apartments as well as offices.

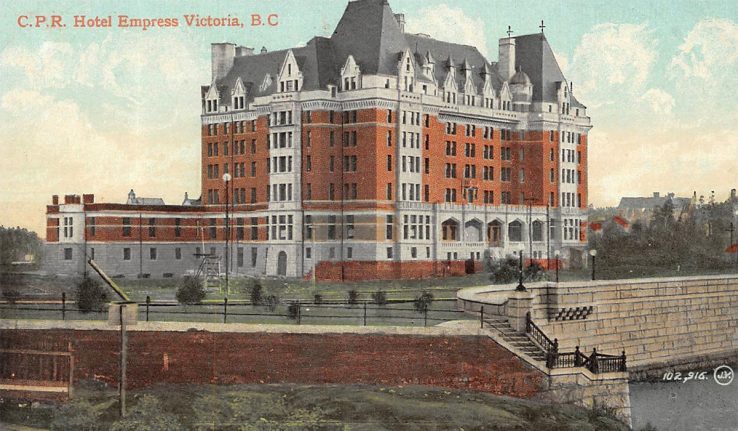

The Empress, Victoria

The Empress hotel in Victoria, British Columbia, was built in the first decade of the twentieth century to accommodate Canadian Pacific’s steamship service, whose main terminal was just one bloc away. When Canadian Pacific ceased its passenger services to the city, the hotel was successfully remarketed as a resort to tourists.

The interwar years were the hotel’s heydays. Edward, Prince of Wales waltzed into dawn in the Crystal Ballroom in 1919. His brother, then-King George VI, and his wife, Queen Elizabeth, attended a luncheon at the Empress in 1939. Shirley Temple, the American actress, stayed there to escape kidnapping threats in California.

In the 1960s, it looked like the Empress might be demolished to make way for a modern, high-rise hotel, but local opposition thwarted this (diabolical) plan. Instead, the hotel was renovated.

Another renovation followed in 1989, when a health club and indoor swimming pool were added. The most recent restoration was in 2017.

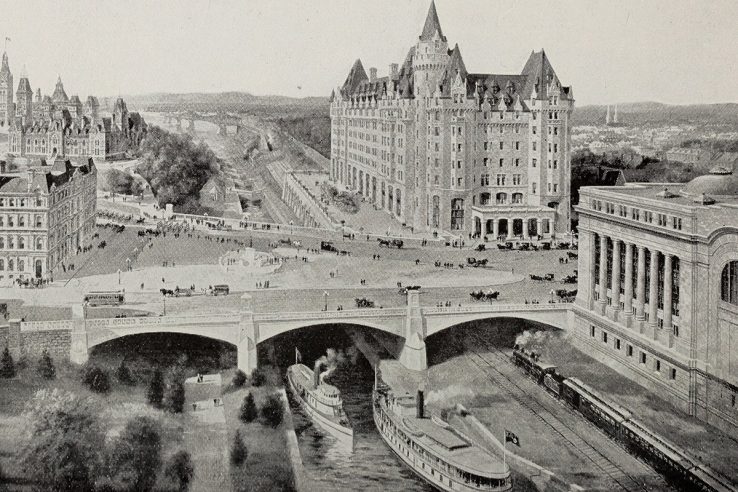

Château Laurier, Ottawa

Built in tandem with Ottawa’s downtown Union Station between 1909 and 1912, the Château Laurier was built by Canada’s Grand Trunk Railway, which later merged into the Canadian National Railways. The hotel was named after Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, who supported its construction.

Although it looks French from the outside, the interior of the hotel is more English or Scottish. Until a restoration in the 1980s, the lobby featured dark-oak panelling and a railed gallery overlooking the double-height space and trophies of the hunt.

An east wing was added in 1929, adding 240 rooms to the hotel. An Art Deco-style swimming pool and spa were added the following year.

The hotel was the place to be and be seen in those years. Richard Bedford Bennett, a native of New Brunswick, lived in the Château Laurier during his stint as prime minister from 1930 to 1935. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s English- and French-language radio stations operated out of the hotel’s top floors from 1924 to 2004.

Given its proximity to Parliament Hill, the American Embassy and other government buildings, and the fact that it has hosted many political meetings over the years, the hotel is sometimes referred to as “the third chamber of Parliament”.

Fort Garry Hotel, Winnipeg

Also built by the Grand Trunk Railway, the Fort Garry Hotel was the largest building in Winnipeg, Manitoba when it opened in 1913. The architecture was inspired by the Château Laurier as well as the Plaza Hotel of New York, which had been built six years earlier.

Canadian National Railways took over the hotel when it acquired the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in 1920. The prominent John Draper Perrin family of Winnipeg bought it in 1979. It was later operated by a Quebecer hotelier. Now it is an independent hotel again.

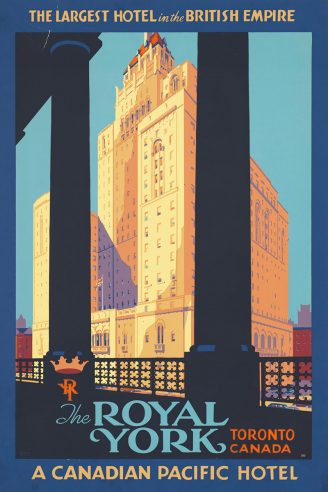

Royal York, Toronto

Built across the street from Toronto’s Union Station, the Royal York was the tallest building in the British Empire when it opened its doors in 1929. It was state-of-the-art. The hotel had ten elevators to reach all 28 floors. All 1,048 rooms were equipped with radios and private showers. Amenities included a concert hall and a golf course. Opening night, on June 11, 1929, was the city’s most exciting social event of the year.

The hotel was modernized in the early 1970s. The marble pillars in the lobby were covered with wood panelling, contemporary wall lamps were added and the rugs were replaced with carpet.

Some of these changes were reversed in the late 1980s, when the Royal York underwent a $100-million restoration. A health club and pool were also added. The hotel’s in-house nightclub, the Imperial Room, was converted into a ballroom and meeting hall.

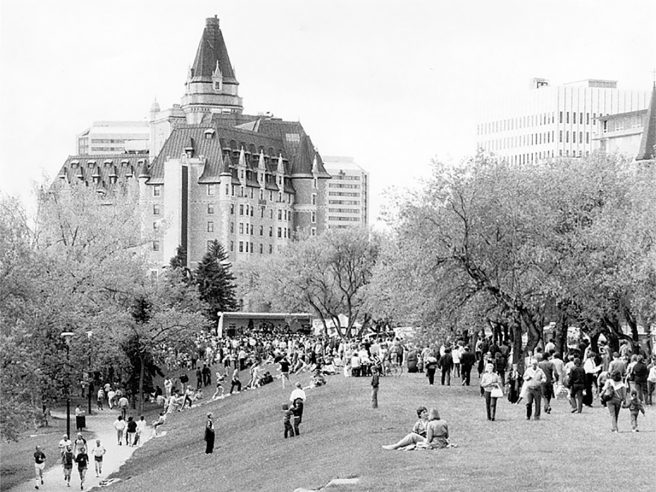

The Bessborough, Saskatoon

The Bessborough (or “Bess”) in Saskatoon, the largest city of Saskatchewan, was built by the Canadian National Railway in the early 1930s. Deliberately resembling a Bavarian castle, the hotel was named after the governor general of Canada at the time, Sir Vere Ponsonby, the Earl of Bessborough.

The Depression delayed the hotel’s opening until 1935. It was hailed as a sign of progress for what was still a relatively small city at the time. A railway hotel put Saskatoon on the map.

A $9-million restoration was completed in 1999 to return many of the hotel’s historical features.