The centennial of the Sykes-Picot Agreement has flooded the better-informed parts of the Internet with everything from the depressingly familiar (blaming the treaty for all the Middle East’s problems) to the refreshingly critical. There seems to be more and more of the latter, which is heartening.

Sykes-Picot was after all not the only plan to partition the Ottoman Empire after World War I, as Middle East expert Adam Garfinkle writes in The American Interest. And blaming it, or any Western design, for imposing “artificial borders” on the region is a dangerous proposition. Taken to its logical conclusion, the idea that only borders that perfectly encompass certain ethnic groups are legitimate invites more conflict, not less.

The Middle East is not the only part of the world that can attest to that. Here are five examples where drawing lines on the map caused even bigger problems.

1. The patchwork that is Bosnia and Herzegovina

We’ll start in the region where attempts to draw the “right” borders for every ethnicity and religious group have caused possibly the longest tragedy. It even gave us a word for it: Balkanization.

From the Ottoman retreat from the region, beginning with the Turk’s defeat in the 1768–74 war with Russia, to the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the people of the Balkans have been shifted first between empires and later between states, most of the time without being asked for their opinion.

The history is too long and too complicated to rehearse in a few paragraphs. Let’s focus on one recent episode to make a broader point.

In 1995, world powers helped bring about an end to nearly four years of fighting in Bosnia by splitting the country in two. Named after the city in Ohio where the accord was signed, the Dayton Agreement created a Republika Srpska for ethnic Serbs (who are mostly Orthodox Christian) and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is itself divided into ten autonomous cantons that are controlled by Bosniaks (mostly Muslim) or Bosnian Croats (mostly Catholic).

As a result of ethnic cleansing and forced relocation during the war, the two new entities were more homogenous than the areas had been in the past. But a third of the Serb Republic’s population is still estimated to be non-Serb while a Serb minority (size unknown) remains in the federation.

The Dayton patchwork has kept the peace but entrenched ethnic divisions. Parties are organized along ethnic lines. Every political appointment must be considered within the context of ethnic politics. The presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of three members: a Bosniak, a Croat and a Serb. Minorities, like Jews and Roma, are ineligible.

Nor has the agreement ended ethnic tension. Serb nationalists still demand more autonomy from a central government that is among the weakest in the world. Some dream of joining neighboring Serbia, where their nationalist counterparts support the annexation of the Bosnian enclaves as compensation for giving up ethnic-Albanian Kosovo.

Clearly, finding the “right” borders is not in itself going to end every ethnic or sectarian conflict.

2. Joseph Stalin’s Central Asian shenanigans

Then again, deliberately drawing the “wrong” borders is always a recipe for disaster.

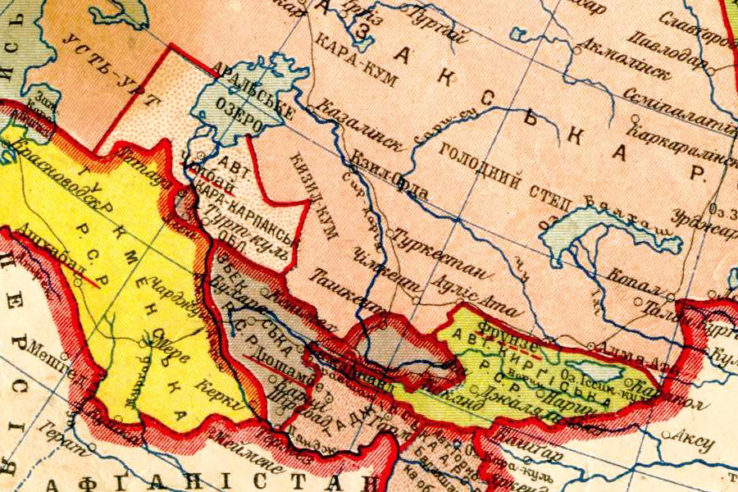

In the early 1920s, Joseph Stalin, the later Soviet dictator, was put in charge of reorganizing the socialist republics that had sprung up in Central Asia. Some, like the Bukharan People’s Soviet Republic, simply replaced the emirate that had preceded it. Others, like the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, were more ambitious: it sought to unite all Turkic-speaking peoples of the region in a single state.

In its infancy, the Soviet Union encouraged such national self-determination. Some of the revolutionaries who created the aforementioned republics saw the Bolsheviks as allies against the tsarist regime.

But Stalin worried that giving non-Russians too much autonomy would doom the multiethnic Soviet Union. As commissar for nationalities, he divided Central Asia into five republics, which survive to this day. Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, Turkmen and Uzbeks are all majorities in their respective republics, but that wasn’t always the case and each had large-enough minorities of the other to make trouble from the start.

A decade later, Stalin added insult to injury by abolishing cultural and language institutes in favor of Russification and moving entire ethnic groups around the communist empire.

When World War II broke out, hundreds of thousands of so-called Volga Germans were forcibly relocated to Kazakhstan. Many thousands died on the way. The ones that made it helped tilt the republic’s ethnic balance in favor of non-Kazahks. By 1970, ethnic Kazakhs were a minority in their own country. Only after the Soviet Union’s collapse, when millions of ethnic Russians and hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans moved out, did Kazakhs form a majority again.

The ethnic tensions that Stalin stirred in Central Asia never went away. Tajiks, a Persian-speaking people, still live uncomfortably alongside Turkic Uzbeks in Bukhara, Samarkand and Surxondaryo. Kyrgyzstan has existed in a near-constant state of turmoil for the last twenty years with riots and revolutions often pitting ethnic Kyrgyz against Uzbeks, especially in and around the ancient city of Osh.

3. Expulsion of the Germans from Eastern Europe

Only a few years after the Volga Germans were collectively punished by the Soviets for the actions of their ancestral homeland, an even larger group of Germans was uprooted from Central and Eastern Europe.

As many as 31 million ethnic Germans and German citizens were cleansed from areas the Nazis had planned to incorporate into their Greater German Empire. Between 12 and 14 million resettled in Allied-occupied Austria and Germany, with the largest groups coming from East Prussia, Eastern Pomerania and Silesia, areas that had been under German control for centuries but were ceded to Poland after the war.

The flight took a heavy toll. Fatality estimates vary, but most recent studies put the figure around half a million.

The expellees that made it found themselves unwanted in a country devastated by war. They organized and made their voice heard in the early federal republic, winning nearly 6 percent of the vote in the 1953 election.

Mindful of the dangers a restive, nationality-based movement could pose, Konrad Adenauer’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) drew the expellees into a coalition government and enacted a Federal Expellee Law, which extended citizenship to the refugees. This took the winds out of the expellee movement’s sails; many switched to the Christian Democrats who, as late as the 1980s, formally called for the reintegration of Prussian lands into Germany.

It wasn’t until 1990, after the Berlin Wall had come down and East and West Germany reunified, that the country relinquished its territorial claims east of the Oder-Neisse line with Poland.

4. Poland’s changeability on the map

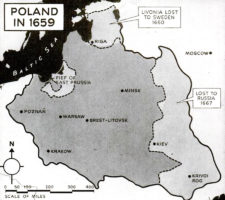

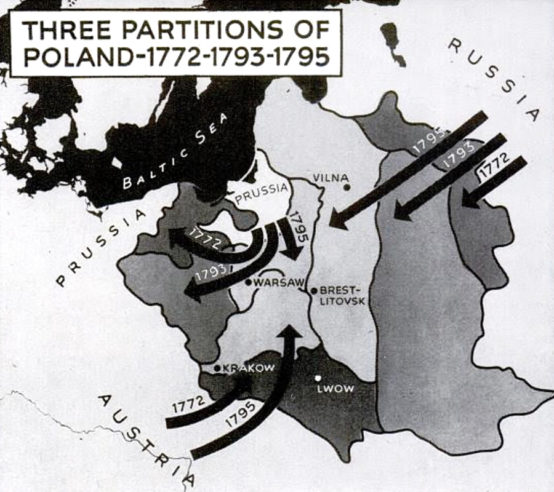

Poland itself has been subject to dramatic changes on the map. It went from one of the largest states in Europe as a commonwealth with Lithuania in the seventeenth century to disappearing from the map altogether in the nineteenth.

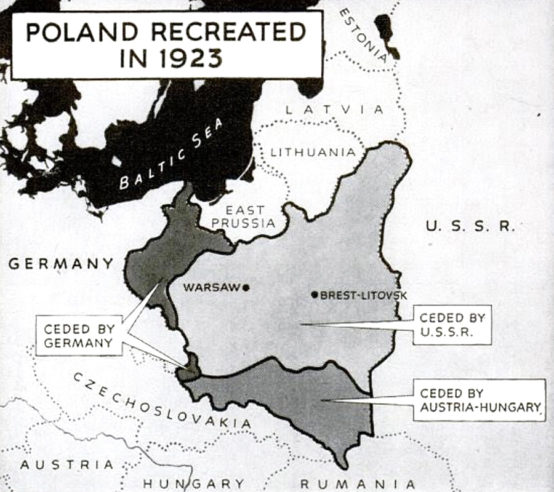

These territorial shifts had a profound impact on Poland’s political and social composition. It is now a century after Poland was restored but differences persist between those parts that were ruled by Germans and those that were part of Austria or Russia. Election maps can be drawn almost perfectly along these old lines: liberal, pro-European parties do well in the formerly German west while conservative, Euroskeptic ones win in the east.

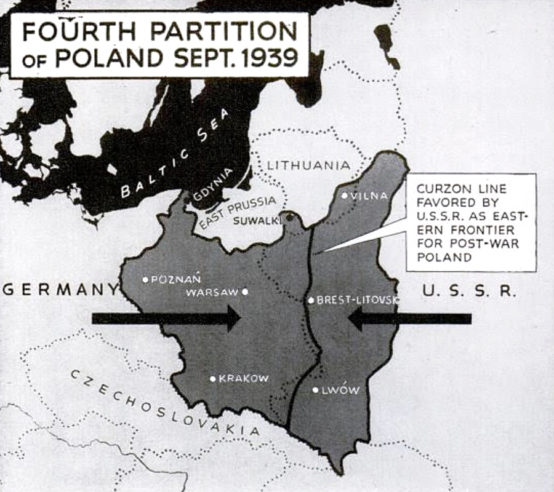

The European powers did not dismember Poland at once. They went through three rounds of partition between 1772 and 1795. Then Napoleon’s France revived it as a puppet state, the Duchy of Warsaw, in 1807. The Congress of Vienna, which withdrew the map of Europe after Napoleon’s defeat, restored Poland in 1815, but it was gradually absorbed by Russia in the years thereafter. When it was restored again after World War I, British foreign secretary George Curzon proposed a border further to the west that came to be known as the “Curzon Line”. It wasn’t implemented at the time; the allies restored “Congress Poland” instead. But the Soviets fell back on Curzon’s proposal at the end of World War II to claim Poland’s Eastern Borderlands, which were added to the Belarusian, Lithuanian and Ukrainian Soviet republics. Poland was compensated with territories in the west, taken from the defeated Germans.

Around one million Poles were transferred from the Russian borderlands to these “Recovered Territories” in the west.

As far as ethnic displacements go, this one was relatively bloodless and many ethnic Poles actually wanted to leave the Soviet Union.

It ended up making the west of Poland more cosmopolitan, which goes some way to explaining its more liberal outlook today. The east, by contrast, which was under direct Russian control for much longer, saw fewer population changes. Family and local ties there stretch back centuries, hence its more conservative instincts.

5. The impossible partition of India

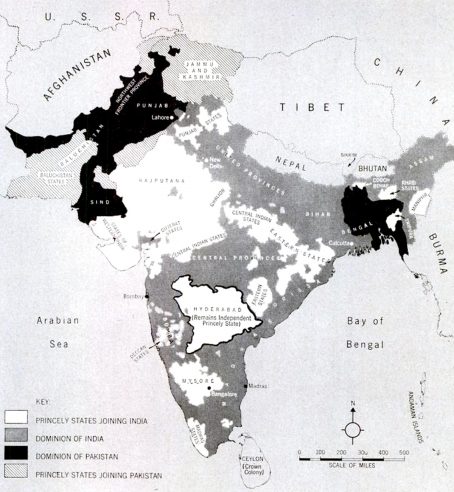

Speaking of Britons drawing lines on the map, perhaps the most consequential in history was a little-known civil servant, Cyril Radcliffe. A lawyer by training, Radcliffe was given the impossible task of partitioning British India into Hindu- and Muslim-majority states.

Radcliffe had never been to India before 1947 and only got five weeks to complete his work. Two members of the Indian National Congress, representing the new India, and another two from the Muslim League, representing what would become Pakistan, were supposed to help him out. But the four often deadlocked, forcing Radcliffe to make all the difficult decisions.

The Welshmen didn’t start from scratch. The British had mapped the subcontinent extensively through the years, including the preponderance of Hindus, Muslims and other sects in given areas. Radcliffe could also take natural boundaries, like waterways, and irrigation systems into account.

But the information available to him was far from complete and even if he had had all the facts — as Radcliffe himself would later say to justify his decisions — some people were bound to end up on the “wrong” side of the border.

The Punjab, straddling the Indus River, had changed hands between empires for centuries. It was populated by Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, not to mention a score of ethnic and language groups. No border there would have been perfect.

But no one expected it would be a calamity. In the end, some 14 million people — roughly seven million from each side — fled when they discovered that Radcliffe’s lines on the map would leave them under the control of the other. There were communal riots. People died from exhaustion on the road. Nobody knows how many perished. Estimates range from 200,000 to a million. No doubt it was one of the largest and most lethal population transfers in history.

1 Comment

Add YoursAfter Sykes-Picot, you have the never-implemented partition plan of the Mandate of Palestine.