Usually, when people seek a look for steampunk, or a setting for a character or story, their minds take them to the grimy streets of London or a city somewhat based upon that hub of Victorian life. Such is all well and good, with plenty of opportunity for urban adventure and the fantastical, technological elements which lend steampunk its science-fiction heart.

In Grandville, the setting switches to Paris and we can visually see Bryan Talbot’s wonderful art work bring to life the Belle Époque-esque steampunk France, but nevertheless the urban setting doesn’t disappear.

However, that’s not the sum of it. In S.M. Stirling’s Peshawar Lancers (2002), we see a wonderful steampunk world mostly featuring agrarian northern India as the new seat of the British Empire after an apocalyptic meteor strike in the 1870s.

Toby Frost’s steampunk science-fiction series Space Captain Smith takes his characters into the unknown frontiers of the British Space Empire, including planets based on India and combines elements of steampunk science fiction and frontier adventure.

The comic series Virtuoso is the closest example which comes to mind; the story of a weapons manufacturer set in a part of Africa which becomes a steampunk technocracy. While it retains the cultural influences of Africa, is still a great comic series, it misses what I feel is part of the appeal of nineteenth-century Africa; the rugged frontier element.

This is a somewhat arrogant view — that while London can be a technologically advanced city of gears and steam power, Africa’s cities and regions must remain the plains, jungle, veldt and desert with kraals and European settlement cities being the only good ones.

Aside from this, however, there isn’t much steampunk “stuff” set outside an urban scene and those which take a setting within the British Empire are often limited to London.

Age of Exploration

This is a shame as the British Empire incorporated hundreds of cultures and spread across a third of the world. Whatever one’s historical interpretation of the empire as good, bad or just neutral historical institution, one cannot underestimate its influence throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

During that period of Victorian civilization, heroes were usually those who were away from the urban centers, performing daring-do in the far-flung corners of the empire.

The same went for France and the United States. The frontiers of their respective empires naturally furnished suitable setting for adventure. Weird West tales are a good example of this employment of the rugged frontier, away from civilization, as a setting for adventure tales within the steampunk genre.

H. Rider Haggard’s famous creation Allan Quatermain was the principle protagonist of the steampunk tales of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, created by Alan Moore, a series which is much more far-roaming than many steampunk settings, but nevertheless not so much set in the frontier realms of the British Empire which became the subject of so much interest toward the end of the nineteenth century — Africa.

As the imperial powers entered into Africa’s interior in the famous “scramble,” their agents brought back tales of the “dark continent” which astounded and amazed readers and listeners. It was a golden age of exploration, much of it by private individuals less interested in imperial expansion than they were driven by the pursuit of fortune and glory.

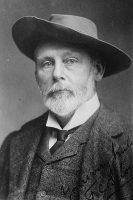

Frederick Courtney Selous

Such a man was the prime influence for Haggard’s Quatermain: the great hunter, adventurer, zoologist and conservationist Frederick Courtney Selous.

Selous, born in 1851, set out from London at the age of nineteen to make his fortune in the Cape Colony, as it was then. Not long after his arrival, he set out into Matebeleland (part of present day Zimbabwe) and gained permission to hunt ivory from its king, a rare honor for white men.

During the course of his adventures, Selous rose in fame and published a number of books. He became a household name as an adventurer and explorer to rank with Stanley and Livingstone. His books on his travels in East Africa, and also his volume on his Canada hunting trip, are glimpses into an age when some of the world’s surfaces were still much unexplored and, to be mapped would require the hard grit and tenacity of these tough but knowledgeable explorers. who embodied the Victorian values of Anglo-Saxon stoicism and enterprise.

Philip Jacobus Pretorius

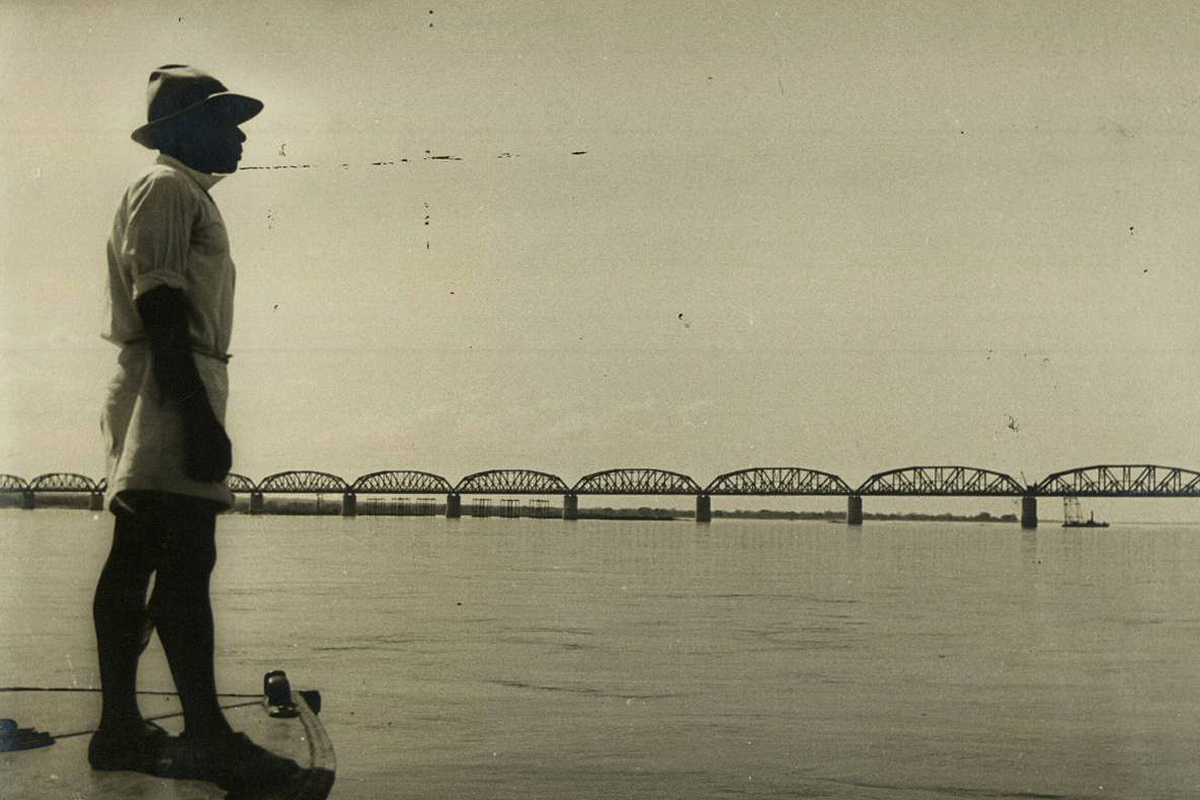

The Boer contemporary of Selous, P.J. Pretorius, was another great white hunter of the prewar era. Known as “Jungle Man,” he lived deep in the Bundu and would go without contact with other Europeans for years at a time, hunting ivory in the Rufiji and further afield.

When the Shütztruppe sought to confiscate his land, he defied and threatened to exhaust the region of its ivory; rendering it worthless to Wilhelmine Germany. He promised to resist arrest, even if the entire German army were sent to find him.

However, he could not make true his claim and was shot in the legs and so began the remarkable story of how this adventurer journeyed over two hundred miles to the nearest British outpost with bullets in his leg.

On his travels, he came into knowledge of the locale of the German cruiser Konigsberg, hidden in the Rufiji Delta, and so for the first time in history an African big-game hunter became a vital tool in cruiser warfare as Pretorius offered his services to the Royal Navy.

Years later, Pretorius put the remarkable details (covered much better than here!) in the book Jungle Man at the behest of his friend Jan Christian Smuts, former Boer commander, prime minister of South Africa, general in the British Army and inventor of Holism, another of Africa’s personalities seemingly imported from the pages of adventure fiction and whose biography is also well worth the read.

Heroes and villains

One must concede, however, that Africa is somewhat tainted. White heroes in Africa may seem to be heroes for some, but it must be remembered that they can be interpreted as wicked villainous imperialists or thieves by many others.

Fortunately for Selous and Pretorius, they are favored in history by and large and Tanzania’s largest game reserve is named in honor of the former.

J.C. Smuts, for his stand against the British, is held as a Boer hero. Later, as a general in British service, he is respected by the British. And for his stand against apartheid in the 1948 election, he is looked on as one of the better white rulers of South Africa. He is often voted by black and white South Africans as the second-best prime minister in the history of that country.

Nevertheless, others, such as Cecil Rhodes, are somewhat rightly condemned by us today as exploiters.

Africa’s rich setting

We must judge the past by its own standards and not our own, this is true, but for the purposes of modern science fiction with a Victorian bent, it can seem very anachronistic to have white heroes in Africa and one must look to indigenous Africans as well to furnish one’s stories with great characters, past such caricatures as Rider Haggard’s Umslopogaas; the Zulu warrior sidekick of Quartermain.

Africa’s cultures furnish a large part of her setting for adventure fiction and anyone with an author’s knowledge of that variety of peoples, languages and beliefs could craft a fine steampunk tale set there with the requisite respect and admiration for what they speak of, and not of a critical or arrogant leaning.

It can be difficult to show another culture in fiction without seeming to patronize, but when one sees what Africa can offer, particularly to Victorian science fiction, it is my humble belief that one should try. To ignore the setting in case of offense is to undervalue it for what it is: one of the most beautiful continents in the world possessive of a vibrant history, black, white and Indian Asian, and to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Part of the issue in underappreciating Africa is that many if not most steampunk are white, very few of them black, even fewer actually in Africa. This subject was tackled in an article at The Gatehouse some months back, when the subject of racial minorities and representation were addressed, unfortunately with backlash which only took the issue back into “we can’t talk about that” territory.

So I appeal to any budding steampunk authors out there to — should you want to — grab the Impi by the horns and give Africa a fair representation within steampunk literature; utilize her history, cultures and characters to blend a great adventure yarn set either in the frontiers of the Rufiji or Masaai Maras, the veldt or in African cities of wonder, such as in Virtuoso.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 21 (November 2011), p. 5-7, with the headline “African Adventures”.

2 Comments

Add YoursI am really enjoying this site. Very similar interests – I am particularly into pre-Modern architecture and city-scapes.

While not Africa, the British Raj gave rise to the Indo-Saracenic style of architecture – an East meets West style, which is one of the most impressive forms.

I often imagine how much better and more interesting the built world would be today if Modernism/Internationalism had never taken root (the much more beautiful and artistic arch. styles & schools partly died as they were associated with the Old Order of Empires and Monarchies that had brought on two world wars and devastated much of the world). Less is More, Efficiency-above-all Modernism was a top-down movement and a reaction against the “buildings of kings” and the White City on a Hill – in my opinion the acme of human buildings & cities: 1880 – 1920.

Look forward to exploring the rest of the site.

Thank you so much! You may be interested in our various #Disney stories as well.