A little-known chapter in the history of aeronautics is the attempt to reach the North Pole by airship.

Salomon August Andrée

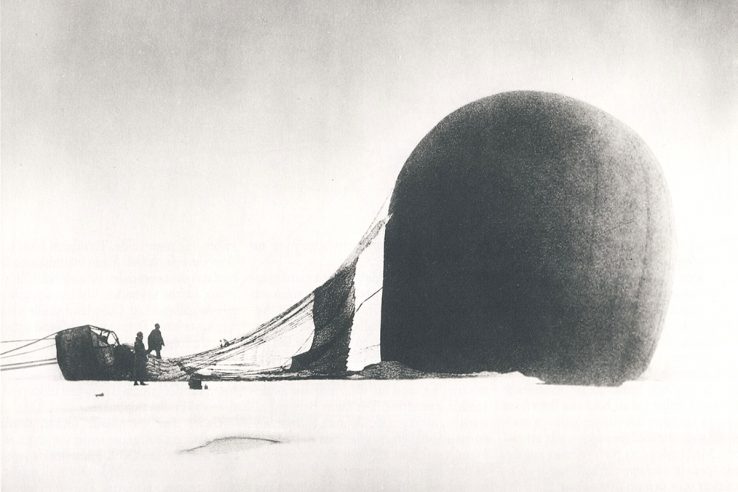

The daring Swedish adventurer Salomon August Andrée was the first to try. He and two companions made an attempt on July 11, 1897.

From the very beginning their adventure was doomed. He did not use a real airship, rather he employed a hydrogen balloon, the Örnen (Eagle). This balloon had severe technical difficulties and right from the start was leaking hydrogen and proved unable to gain altitude, repeatedly hitting the pack ice. Ultimately the endeavor had to be abandoned after only a few hours of flight.

Andrée and his men than set out to walk back over the ice toward Spitsbergen, a journey for which they were not equipped. After 83 days they reached Kvitøya, 400 kilometers east of their base camp. There they were caught by the sudden onset of winter. Sadly, all three perished on Kvitøya. Their remains and final records were not found until 33 years later.

Walter Wellman

The next to set out was the American journalist Walter Wellman. Wellman was already a renowned adventurer who had led an expedition to the Arctic in 1898.

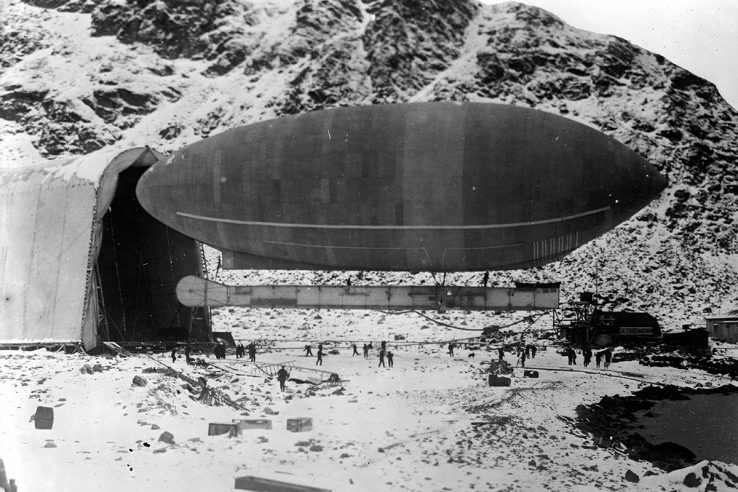

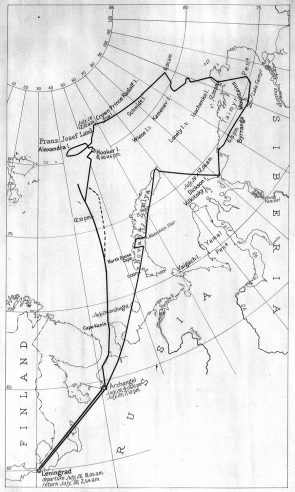

His first attempt to reach the Pole by airship was announced on New Year’s Eve of 1905 and the airship was built in Paris. He also had a hangar erected at Virgor Harbor, Spitsbergen, with a large base camp at the same location. The hangar, however, was never used for the expedition. On the first trial run of the airship’s engines in Paris, they self-destructed, setting Wellman’s plans back by two years.

The next try did not go as planned either. Strong and unfavorable winds delayed the launch of the expedition well into August of 1907. In September, Wellman ordered a successful, if rather short trial cruise before returning to the United States.

Wellman made a final attempt to reach the Pole in the Airship America in 1909, but again disaster struck. After about sixty miles of flight, the America lost its ballast line and had to perform an emergency landing on the polar ocean. Wellman and his crew nearly drowned but were saved by a Norwegian ship.

Roald Amundsen and Umberto Nobile

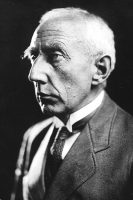

Wellman never returned to the Arctic. It would not be until 1926 that an airship would actually reach the Pole and it had an illustrious captain, Roald Amundsen.

The gifted engineer of Amundsen’s airship Norge, Umberto Nobile, deserves much of the credit for the mission’s success. Throughout the flight there was much friction between the highly egocentric Amundsen and the Italian Nobile: the former could hardly bear the presence of someone equally able and successful as himself. Their friendship broke, despite or maybe because of their shared success.

In a strange twist of fate, a later journey by Nobile to the Pole in his airship Italia in 1928 (without Amudsen participating) would prove to be Amundsen’s doom.

Nobile reached the Pole, but on the journey back the Italia crashed and a massive rescue operation was launched. Among the participants was Amundsen, who died when the Latham 47 flying boat he was a crew member of crashed. The bodies of Amundsen and the rest of the crew were never recovered.

Graf Zeppelin

The final journey by airship — and from a scientific point of view the most successful, judged by the amount of data collected — came in 1931.

The LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin cruised in the Arctic for a week, originally to meet a submarine owned by the Australian explorer G.H. Wolkins there. This would have been a true steampunk event, having a zeppelin meet a submarine in the polar seas. The rendezvous was called off, however, when the submarine was scuttled due to age and technical difficulties before the start of the Graf Zeppelin‘s polar cruise.

The Graf Zeppelin took detailed measurements of the area surrounding the North Pole and collected a huge amount of data, which for the first time made a complete picture of the polar region possible.

The one remarkable thing about this journey was its financing: it was planned and executed during a time when the Weimar Republic was still shaken by the economic crisis of the late 1920s. The money was gathered by an extraordinary marketing trick: The LZ-127 was carrying thousands of airmail letters which were stamped with a special “North Pole stamp” once the zeppelin reached the Pole, making them highly collectable. There were thousands of people in Germany willing to have such a letter and as such willing to finance the project.

Progress

The dash for the North Pole by airship and zeppelin remains a remarkable example of human endurance, determination and inventiveness. It also shows the spectacular technological progress made in the mere 45 years between Andrèe’s first attempt in 1897 and the comparably very comfortable and safe week-long cruise of the Graf Zeppelin in 1931. In less than a generation, humans had been able to turn one of the most remote and inhospitable places on the planet into a location that was and still is relatively easy to reach.

It is a shame that airships have fallen out of favor with the masses, as they could provide travelers with such magnificent views over the Arctic landscape while slowly cruising over it.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 10 (January 2010), p. 14-15, with the headline “To the Pole by Balloon”.

1 Comment

Add YoursThe ill-fated 1928 ITALIA flight was the subject of the excellent 1969 Russian/Italian movie THE RED TENT, starring Peter Finch as Nobile and Sean Connery as Amundsen. Nobile saw and liked the movie (he died in 1978).