Much of the Howard Hughes legend was well dramatized in the hit Hollywood film The Aviator (review here), starring Leonardo DiCaprio. With some alterations for narrative, the film was a great success and provided the viewer with a good understanding of Hughes and his eccentricities.

However, the film ends well before Hughes himself passed away in 1976 and left many details of his life uncovered.

Start in motion pictures

Howard Hughes was born on December 24, 1905 in Houston, Texas, the heir to wealthy businessman, Howard Hughes Sr., who ran the family business: Hughes Tool Company.

Hughes Jr. was unremarkable at school and never graduated his high-school diploma, however, by influence of his father he was able to sit in on some classes at a technical college.

Shortly after his eighteenth birthday, Howard’s father died and the family became embroiled in a legal dispute over his legacy. A friend of the deceased tool magnate, who was conveniently a judge, made the young heir a legal adult in 1925, allowing Howard to take sole possession of the company.

His uncle had been of great support to the young Howard and been custodian of the business before he could legally inherit it. The same uncle, Rupert Hughes, was a writer for Goldwyn’s motion picture studios. From this relation the young and eager Howard gained his interest in the motion picture business, which he would first enter into by creating the film Two Arabian Nights in 1928.

Two years later he released Hell’s Angels, the most expensive film then produced at $3.8 million, dwarfing even the follies of the great silent film director Erich Von Stroheim. The movie, financially a flop (loosing over a million dollars), still gave Hughes the lessons in the movie business which he would later use to full advantage when navigating his other films to release despite their controversial natures.

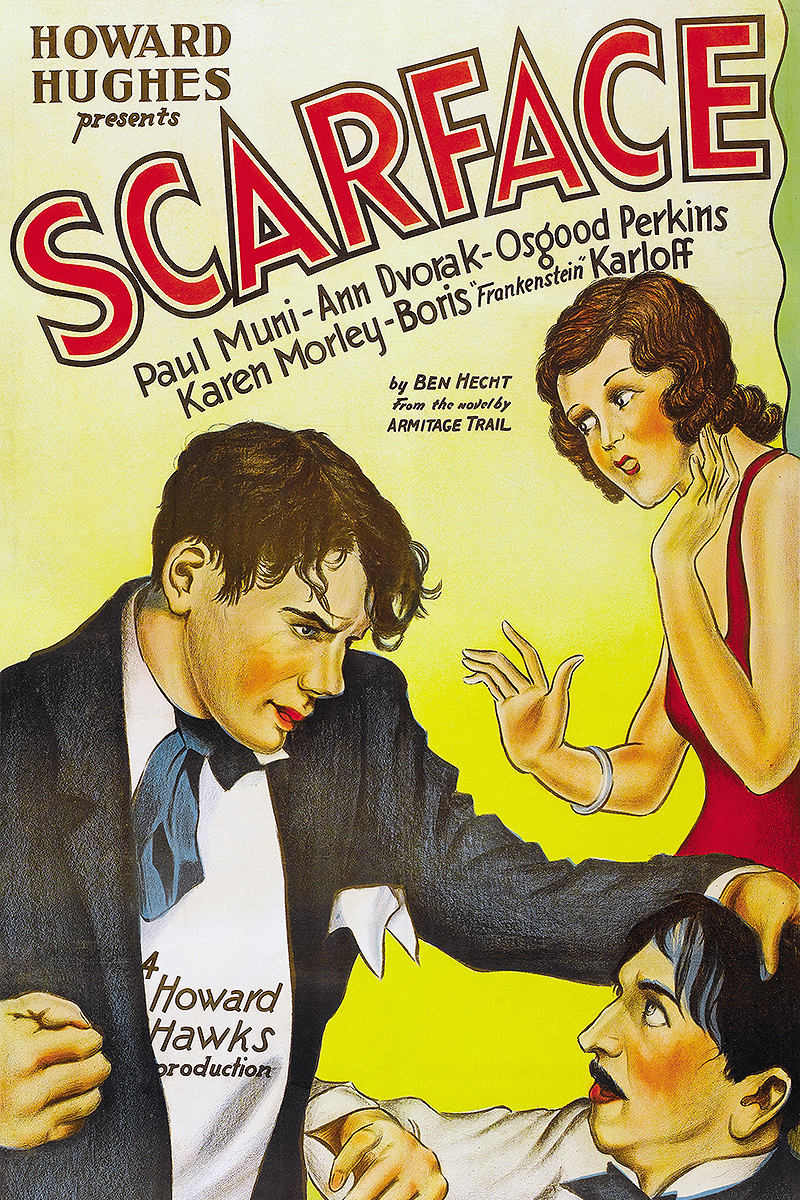

Howard always pushed the envelope with his motion pictures as he did with his other productions. Scarface (1932) was censured for violence and later, in 1941, The Outlaw received similar controversy for its sexual content. Famously Hughes designed a special kind of half-cup bra for the curvaceous Jane Russell so that her breasts would look full enough for her role in the film.

Aviation: Hughes’ true passion

While movies were a hobby, Hughes’ true passion was aviation. He had acquired his pilot’s license on the set of Hell’s Angels and after that there was no stopping him.

In 1932, he set up the Hughes Aircraft Company, a subsidiary of Hughes Tools, which was born out of a project converting a military aircraft of former US Air Service stock to a racing craft. The company later produced the H-1, the most advanced aircraft of 1935, when it broke an air speed record by flying 352 mph.

Again in 1937, a variant of the H-1 Racer, this time with longer wings, won the transcontinental speed record. Hughes later claimed that the infamous Mitsubishi Zero fighter plane of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force was a copy of his H-1.

He topped these records by a round-the-world flight in a customized Lockheed 14, which took only three days and nineteen hours. The New York-to-Paris leg cut the previous record for that journey (set by Charles Lindbergh) in half.

Unreliable contractor

With war looming, Hughes Aircraft concentrated on military contracts, however, Hughes proved unreliable for this as two of his famous follies proved.

Part of the problem was that he insisted on a great level of secrecy and would reveal little of his projects till their final unveiling, even to the USAAF.

He was also reluctant to use standardized materials, knowing that those that he proffered would achieve better results, even though they were more expensive.

Both of his craft flew in 1947, one of them crashing, killing two almost along with the test pilot, Hughes himself.

This was the XF11 spy plane, which was developed for wartime reconnaissance but arrived two years late.

The second project was the one which Hughes is best remembered for: the H-4 Hercules, known to the media and general populace as “the Spruce Goose” for its unorthodox construction of wood due to wartime material constraints. This was to be a joint venture with the shipbuilder Henry Kaiser, who later dropped out due to Hughes’ delays.

Hughes’ albatross

The concept for the H-4 was a “Flying Liberty Ship” to ferry troops over the Atlantic to Britain and Europe without the threat of Germany Navy U-boats, which were costing millions in shipping and material during the Battle of the Atlantic. The idea was sound if unorthodox for its day and in many ways visionary. The contracts were specifically awarded by President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the expense of others which his advisors said would be more feasible. Doubtless Hughes’ influence spanned to the highest corridors of power even then.

Before and during the Second World War, flying boats, as they were known in Britain, or flying clippers, in the US, had performed the duties of modern airliners by transporting passengers across the world in a level of comfort that is now impossible for us to imagine as modern-day airline passengers are crammed into awful plastic seats with microwave food. Travelers onboard the flying-boat routes enjoyed silver service, sleeping cabins and personalized welcoming cards.

At the outbreak of war, these huge vessels were assigned to military duties, yet all were dwarfed by a German craft: the Blohm & Voss BV238. This is perhaps the closest relative to the vast creation of Howard Hughes.

The BV238 was a transport plane prepared for long-range operations with the Wehrmacht. She had a wing-span of 188 foot and 11 inches and was 150 foot, 11 inches long. The H-4 Hercules, however, was a titan among mere Luftwaffe giants and when she flew in 1947, over two years after her need had gone, she was the largest aeroplane in the skies. The H-4 had a fuselage/hull length of 219 foot; 69 foot longer than the massive wingspan of the BV238.

The H-4 was derided by press and public alike and her immense cost ($5 million for just the one craft when the initial order was for three units) brought the attention of a special inquiry by the United States Senate into what was alleged to be war profiteering on Hughes’ part. However, it transpired that Hughes had sunk millions of his own vast fortune into the project.

Unfortunately, the H-4 never flew again after her maiden flight, when she covered just one mile at a height of approximately 75 feet above Long Beach, California. This remarkable craft is on display at the Evergreen Aviation Museum in Oregon.

At the time, the Hughes H-4 was seen as a tremendous joke, however, large aircraft for troop transport are now the norm, such as the C-130, also called the Hercules. The flaw with the “spruce goose” perhaps rests with its flying-boat design. Before the war, the largest planes were usually of this type. After the war, the jet engine and better materials allowed quicker and larger planes to connect cities around the world.

Paranoia

Throughout the 1950s, Hughes built a series of spy satellites for the CIA and other US government agencies, which brought him more and more in contact with both the agency and organized crime. The 1960 election victory of John F. Kennedy might well have been connected to the fact that Richard Nixon’s brother did not pay back a loan to the billionaire aviator. A Hughes employee was also central to the infamous Watergate scandal.

In 1966, Hughes sold his remaining stock of Trans World Airways, a company he had bought in the 1930s. He had fought tooth and claw against rival airways, including Pan America (dramatized in much of the Scorsese film), for the development of the airline and made it into one of the most successful of the postwar era, despite numerous setbacks and board disagreements, often started by Hughes.

Hughes became increasingly paranoid throughout his career, a symptom of his mental illness which had first developed in the mid 1940s, and combined with his obsessive compulsive order to make him a well-known eccentric.

During the Vietnam War, Hughes made much money selling helicopters, including the now widely used and developed Apache attack helicopter. But the same high costs (which the US Army claimed were inflated) and slow delivery times which had made Hughes an unreliable contractor during the Second World War also dogged him in Vietnam. Hughes Helicopters lost out to Bell later in the war.

In April 1972, Hughes practically withdrew from public life altogether after a regression in his illness and conducted business from a set of sealed-off hotel suites. The entrepreneur eccentric finally passed away in 1976, leaving a fortune of $2 billion dollars.

The later scandals of Howard Hughes’ life, and the mental illnesses which plagued him from a young age, seem to detract from the earlier Howard Hughes, which is how your correspondent prefers to remember him: a man who dared to push the envelopes of technology and even legal business practice in pursuit of his passion of aircraft and their design. “I’m not a paranoid, deranged millionaire,” he once said. “Goddammit, I’m a billionaire!”

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 10 (January 2010), p. 5-7, with the headline “The Aviator”.

2 Comments

Add YoursOne fictional portrayal of Hughes, acted by Terry O’Quinn, in a Dieselpunk movie is his appearance in ‘The Rocketeer’ (1991). Hughes is shown as sponsoring the development of jet packs in the 1930s.

Howard Hughes wasn’t uneducated by any means – he spent pretty much all of his time as a boy with the free run of Hughes Tool Company, learning everything from engineering to materials to machining and manufacturing processes and the then-new electrical and electronic systems from some of the most knowledgeable people on the planet, so it’s no surprise he was bored with school. This is far beyond what can be obtained by any combination of degrees, and he was clearly capable of pushing the envelope of what technology could do. (BTW, I learned this first-hand from people who knew him there – he was flaky later, but all of them regarded him as a complete technology genius early on.) I would rank Hughes as among the top engineer entrepreneurs of the 20th century, along with Ford, Chrysler, Edison, Eastman, Land, Moore/Noyce, etc.

Making a good business out of it was another matter: with the exception of Hughes Tool Company (referred to as Toolco by insiders), which already had this culture and was wildly profitable, his other tech ventures (especially Hughes Aircraft and Hughes Electronics) were famously focused on building great products and taking care of customers was secondary, though this later improved once Hughes became less involved. It’s quite true that Noah Dietrich was a needed counterbalance to Hughes’ “irrational exuberance”.

Also, while Hughes himself may well have had a family tendency toward mental illness, he was clearly never the same after he was nearly killed in the crash of the XF-11, which caused literal brain damage and started a lasting downward spiral. (Before the crash, he really was the model of Tony Stark – billionaire playboy pursued by Hollywood stars (not just starlets), engineering genius, and captain of multiple industries – oilfield, airline, aircraft, electronics, movies, etc. He was also good enough at golf to play professionally had he wanted to.)

It’s hard to conceive of someone with Hughes’ influence today – You’d kind of have to combine the kind of big Hollywood studio owner that no longer exists with maybe Elon Musk to get even close. His wealth allowed him to make business mistakes that would have sunk anyone else, but Toolco was an unbelievable cash cow: As the sole owner of Toolco, so he was MAKING A MILLION DOLLARS A DAY in the depths of the depression!