According to the blog The Flying Fortress, there are “two flavors of dieselpunk”: a pre-nuclear “Ottensian” dieselpunk (named after me!), which revels in the bliss and progress of the 1930s, and a post-nuclear “Piecraftian” dieselpunk, which is sometimes post-apocalyptic.

The distinction may be more complicated, as Piecraft himself suggests in the fourth issue of our webzine, the Gatehouse Gazette. He identifies two types of “Ottensian” dieselpunk:

- The “Hopeful Ottensian,” epitomized by the 2004 Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow; and

- The “Dark Ottensian” of films like Delicatessen (1991) and The Mutant Chronicles (2008), in which “the dark pillars of petroleum fumes and engine noises and vehicles no longer bring about sentiments of joyous anxiety and wonder but one of conformity and pollution.”

The Flying Fortress agrees that “everything looked better” in the 1930s.

Men’s and women’s fashion is really stylish and snazzy, especially the military stuff. Workwear had a certain charm to it, too. But just look at those automobiles and manufactured goods, like typewriters and cameras… beautiful.

Hopeful Ottensian embraces the styles and technologies of the era; it imagines the Jazz Age never ended. This is what we like to call decodence.

Deco and ephemera

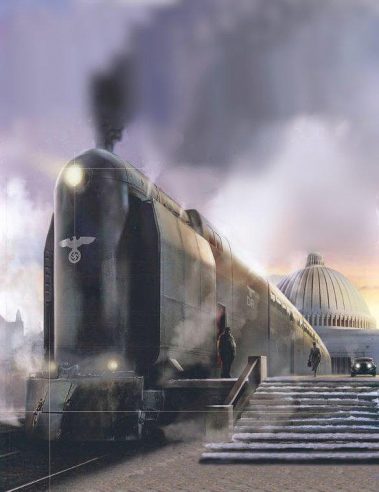

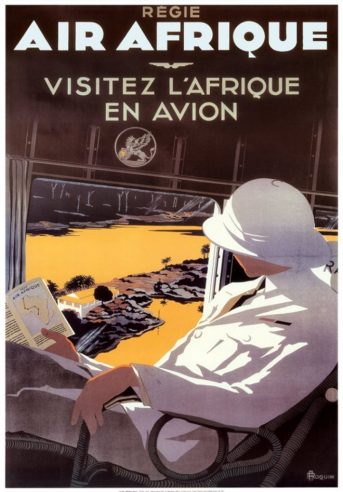

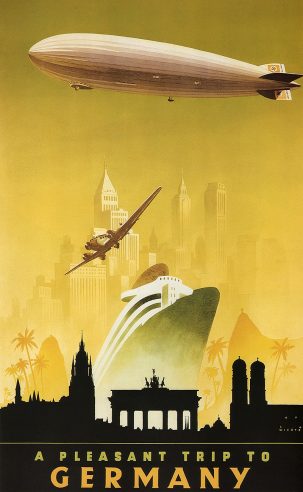

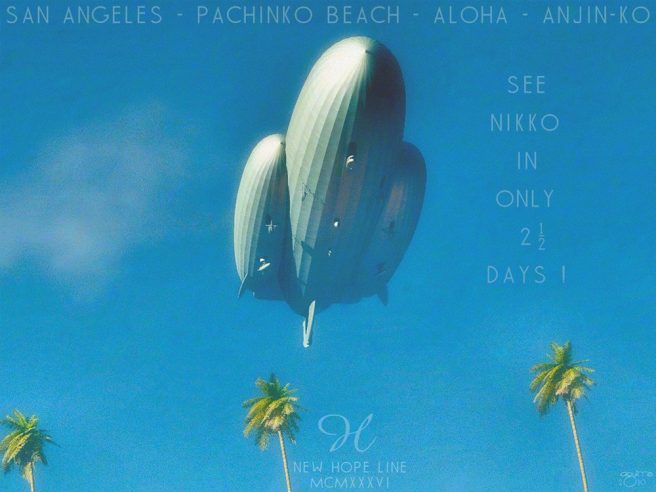

We find the optimism and progress of the 1930s expressed in the travel ephemera of the era. Their Art Deco styles drew inspiration from modern aviation, electricity, the radio, the ocean liner and the skyscraper. It was in streamline styles that this technology fully manifested itself and at the time it was considered elegant and functional and the look of the future — and therefore perfect to evoke a sense of luxury and now.

Art Deco “celebrated the machine age,” according to Ann Mette Heindorff.

Its central characteristics [were] clean lines and sharp edges, stylishness and symmetry.

Deco imagery graced the brochures of travel companies and modern-day artists know how to use it to make their work look vintage.

Whereas airships can feature in both steampunk and dieselpunk, the aeroplane belongs positively to the latter and may actually be the most quintessential of modern technologies defining the genre.

Airlines, which operated a mode of transportation unique to the machine age, employed the best in graphic design from the 1920s and 30s.

Not only ocean liners and aeroplanes underwent a transformation of streamlining and style. Automobiles and trains also appeared gloriously in advertisements and magazines as symbols of modernity and the march of progress. They represented the freedoms and luxury that came with the Golden Age of travel, a time when travel was still very much conducted in style.

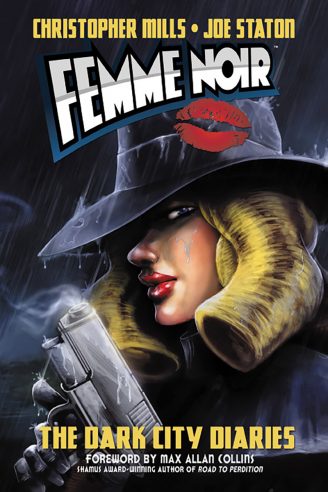

Heroes of pulp

The same 1930s and 40s that seem so styleful and elegant in advertisements were not devoid of less glamorous activity. Dieselpunk also explores the dark side of town, the crime and corruption of hardboiled detective novels and the moral ambiguities of film noir. And, of course, the genre needs heroes to combat those depravities.

Thus we find protagonists “that represent the qualities of the heroic spirit of the times,” writes Piecraft: “a strong sense of morality with a cynical mindset to the world around him attributable to some past personal conflict.”

Such values are defined by the strive to seek a resolution to the perpetuating crises that have developed in the world. Most notably the Nazis are seen to be the root of all wordly woes, as exemplified in the Indiana Jones series, The Rocketeer (1991), Hellboy (1991), the video game Return to Castle Wolfenstein (2001) and even Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004).

He adds, “The characters of Sky Captain and The Rocketeer are the new hope with a ‘can do’ attitude for a generation in a time of turmoil.”

Like the heroes of pulp literature and Golden Age comic books, they are idolized as “adventurers at heart, fearless, yet very human still. The rugged and tough exterior is the stock for most pulp-orientated heroes of the time.”

Just what makes classic pulp heroes like Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe, Dashiell Hammett’s Sam Spade and The King of the Rocket Men (1949) so popular? These men, in spite of their “rugged and tough exterior,” as Piecraft put it, knew right from wrong in a morally ambiguous world.

Perhaps we find the characteristics of the traditional pulp hero best expressed in contemporary homages. Although the motives and actions of Christopher Mills’ and Joe Staton’s Femme Noir may be questionable at times — as can expected from such a wonderful neo-noir installment — the protagonist is portrayed as ultimately just.

The same can be said about the characters in Frank Miller’s Sin City (1991).

The less noir-esque dieselpunk fiction becomes, the less place there is for moral shades of grey. We find no uncertainty about the motives of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon and modern-day homages to those characters like Tom Floyd’s Captain Spectre and Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

“Instead of battling shadowy government conspiracies and evil corporations,” these heroes, according to Jack Rose of the dieselpunk blog Gearing Up, battled “real, obvious bad guys. It was a simpler time and it’s easy to feel a certain nostalgia for that.”

As the dieselpunk protagonist grows more heroic, he gradually becomes a superhero.

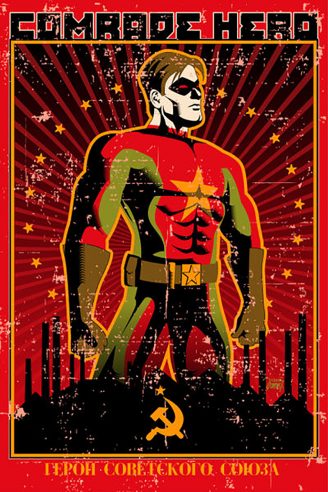

In a world “dominated by petroleum-fueled anxiety,” there is little place for heroes struggling with their own identity and doubts. This world needs Dave Stevens’ The Rocketeer (1982) to thwart the plots of evil Nazis; Iron Man, to fight the Red Menace; and DomNX‘s Comrade Hero to combat the corrupt and decadent West.