It’s unclear who coined the phrase “biopunk,” but presumably the term was invented after steampunk had been established as a genre. At least, it was not until steampunk had entered the mainstream that biopunk emerged.

Like steampunk, this proposed literary genre finds its origins in cyberpunk. It replaces the information technology of cybernetics with the synthetic biology of genetic engineering, but maintains most of the other elements of the genre.

Which begs the question: Should biopunk be considered a genre of its own? And if not, are steam- and dieselpunk really genres in their own right?

The face of cyberpunk

According to Lawrence Person, the genre’s leading theorist, cyberpunk depicts a future “where daily life [is] impacted by rapid technological change, an ubiquitous datasphere of computerized information and invasive modification of the human body.”

Cyberpunk typically features marginalized, alienated loners who live on the edge of that society, hence the reference to punk subculture, echoing the atmosphere of film noir and inspired by hardboiled detective novels. The genre’s vision of a troubled future represents the antithesis of utopian science-fiction, evident from its postindustrial dystopian setting characterized by extraordinary cultural ferment and the application of technology in ways never anticipated by its creators.

Cyberpunk literature is (or was, considering the less dystopian perceptions of postcyberpunk) significant, because it represented contemporary concerns about the shortcomings of urban society, warning against government and corporate corruption, the dangers of pervasive surveillance technology and alienation and indifference. Where cyberpunk is skeptical about progress, postcyberpunk tends to focus on its upsides rather.

Biopunk, however, changes little to the basic premise of cyberpunk, maintaining its dystopian overtones while merely replacing cybernetics with biotechnology.

A worthy successor?

Rather than depicting the marginalized drifters of a society grown indifferent by a rapid evolution of information technology, biopunk portrays the underground side of a biotechnological revolution. Its rebels may be the products of human experimentation, their struggles set against the backdrop of totalitarian governments or megacorporations which abuse biotechnolgoy as a means of social control or profiteering.

The author who is considered to have defined the biopunk genre is Paul Di Filippo, whose collection of short stories published as Ribofunk (“ribo” referring to the full name of RNA; ribonucleic acid) is more reminiscent of detective pulp than cyberpunk.

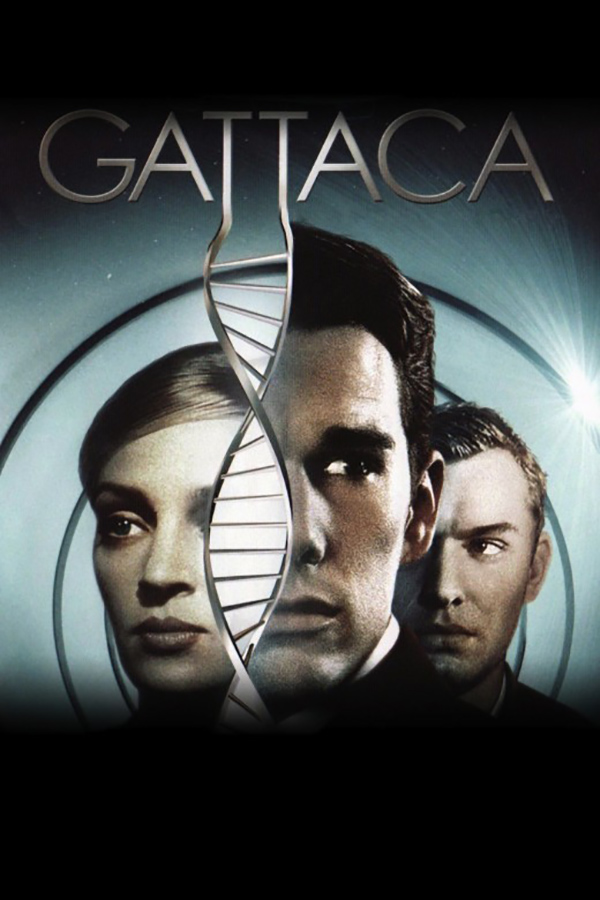

Movies like the 1997 science-fiction drama Gattaca, which depicts selective breeding through preimplantation genetic diagnosis, as well as the 2006 film adaption of V for Vendetta, which features a protagonist with superhuman traits fighting an oppressive fascist regime, an be considered biopunk as well, in spite of their departure from other classic cyberpunk (and, in the case of V for Vendetta, Alan Moore’s original political) themes.

Perhaps the most successful biopunk installment to date is the 2007 video game BioShock, set amid the chaos of what was supposed to be an underwater utopia, now infested with the products of biotechnological abuse.

BioShock, however, takes place in 1960, and while obviously warning against the dangers of genetic engineering, its setting and technology are more diesel- than biopunk.

Indeed, it seems that most, if not all, works of biopunk fiction struggle with the genre to which they ought to adhere. Either they can be considered cyberpunk, differing only in terms of technology, or they could be labeled dieselpunk instead, focusing on the ill effects of genetic engineering in the vain of Nazi human experimentation in games like Return to Castle Wolfenstein (2001) and ÜberSoldier (2006).

The larger cousins

If most biopunk fiction differs little from cyberpunk, it might be better to see it as a continuation of that genre, inspired by postcyberpunk, rather than a genre in its own right.

The few biopunk installments not particularly influenced by cyberpunk, as Paul Di Filippo’s Ribofunk and BioShock, incorporate neo-noir elements and share themes with adventure pulp instead. They may be considered dieselpunk.

But if we don’t accept biopunk as a separate genre, what does that say about steam- and dieselpunk?

The thing is, these genres have less in common with cyberpunk and more distinctive characteristics of their own.

Steampunk shares little with cyberpunk, changing the setting from the future to the past, the technology from modern to old and the protagonists from outcasts to elite. Steampunk is generally more optimistic, romanticizing the past and averse not to modern technology itself but to the lack of appreciation for it.

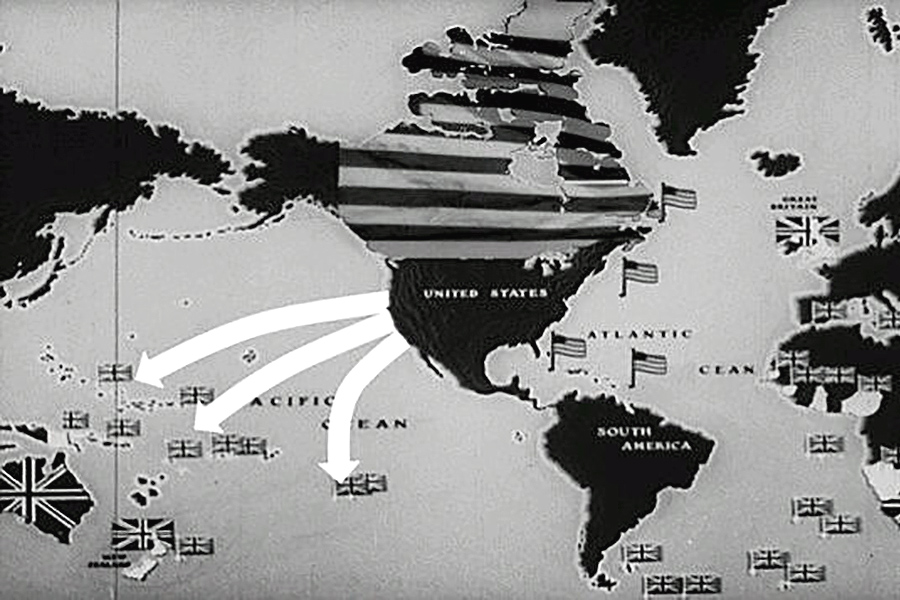

Dieselpunk may thematically be more similar to cyberpunk. It is more dystopian than steampunk and influenced by midcentury pulp rather than nineteenth-century scientific romance. However, unlike cyberpunk and steampunk, it has no critique of our own time.

Conclusion

Biopunk changes little to the basic premise of cyberpunk, depicting rapid technological change and invasive modification of the human body, albeit not by cybernetics but biotechnology. Influenced by the less dystopian outlook of postcyberpunk fiction, biopunk represents contemporary concerns about the shortcomings of society, warning against government and corporate corruption and a lack of control over genetic engineering and the resurgence of eugenics.

The majority of fiction labeled “biopunk” may be considered a continuation, or update, of cyberpunk. Those works of biopunk inspired by midcentury pulp, incorporating hardboiled detective and neo-noir elements, can be categorized under dieselpunk.