Discussing the “dark side of dieselpunk,” the author of the dieselpunk blog The Flying Fortress coins the phrases “Ottensian” and “Piecraftian” dieselpunk to refer to fiction set, respectively, in a pre- or post-nuclear environment.

Where The Flying Fortress starts the “Piecraftian” with the Atomic Age, Piecraft and I believe World War II is the better dividing line between the two flavors of dieselpunk.

Ottensian

The Ottensian dieselpunk, named after my view of the genre, depicts nuclear weapons, if at all, only as an experimental technology.

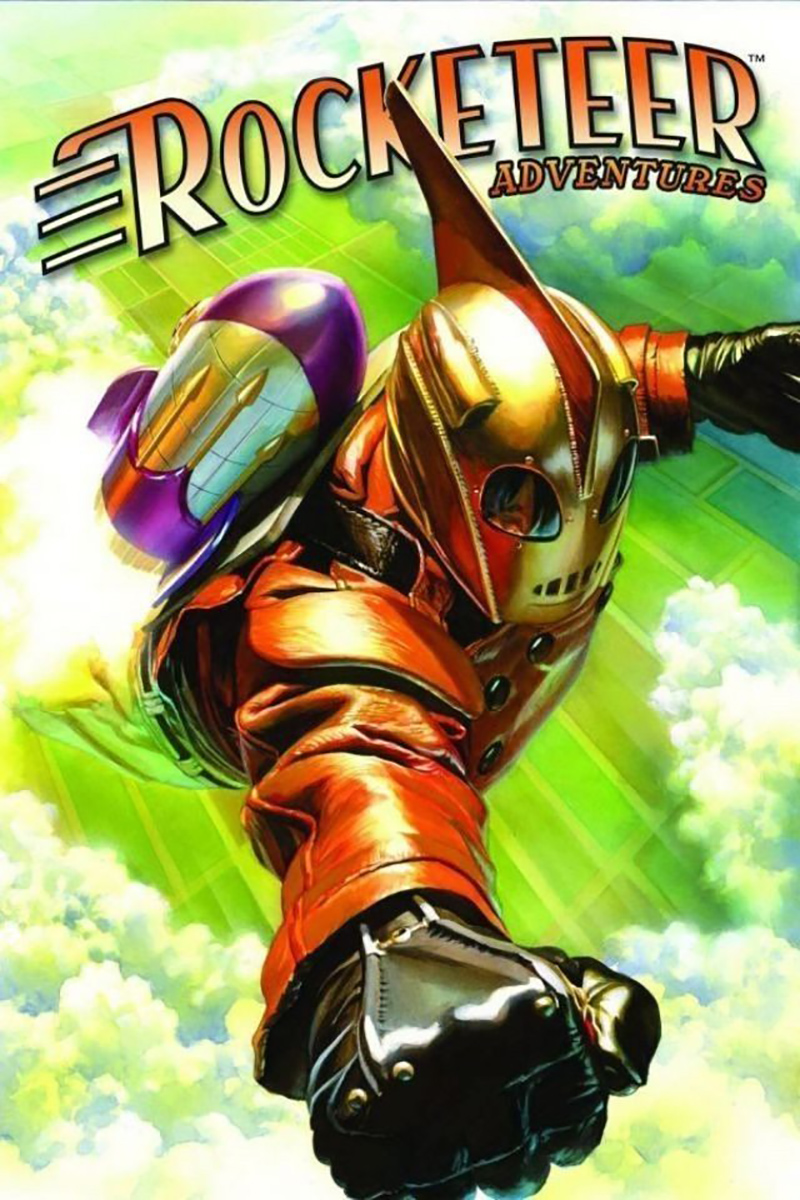

With no Great Depression having occurred in this alternate history, it is a time defined by seemingly unstoppable progress and unfaltering faith in the future. Skyscrapers are erected in Art Deco style, zeppelins still grace the skies. It is perhaps the most attractive type of dieselpunk and certainly the most optimistic.

The Ottensian dieselpunk shares themes and an aesthetic what with is nowadays considered retro-futurism. That is, an enthusiasm for predictions about the future from the past.

In dieselpunk, those predictions have come true, although not in the future but rather in the era in which they were produced. Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004) is the best example. It blends pulp-inspired adventure and a retro-futuristic aesthetic in an almost utopian world.

Uncertainty and fear nevertheless loom on the horizon. The Ottensian has a dark side too. Examples, such as the 1994 film The Shadow and the Japanese animated television series The Big O, show greater film noir influences, imitating not Indiana Jones-type adventures but the hardboiled detective stories of the pulp genre.

Piecraftian

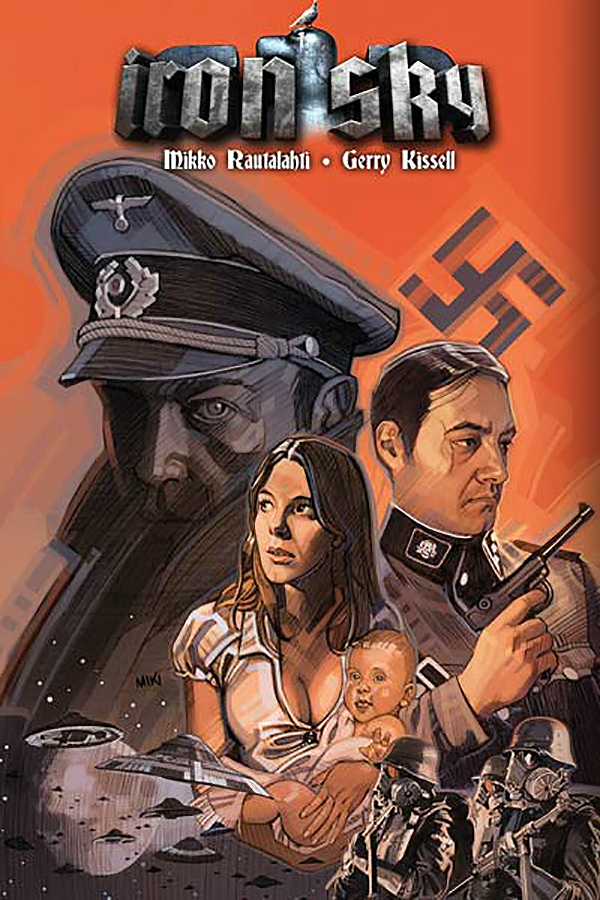

Piecraftian dieselpunk is the gloomy side of the genre. While Ottensian may occasionally venture into darker territory, there is always a glimmer of hope. The Piecraftian, however, is, in the words of Piecraft himself, “more of a continual dystopian view” in the vein of George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four.

In this world, the Second World War is either still being fought as a prolonged Cold War or has been won by the Axis powers. Philip K. Dick and Robert Harris presume the latter in their novels The Man in the High Castle (1962) and Fatherland (1992), which both suggest the continuation of Nazi Germany’s advanced rocketry and jet-fighter programs. The Man in the High Castle even describes the Nazis as “bustling robotic factories across the Solar System.”

Where the Ottensian can be both near-utopian as well as dark, Piecraft describes two different kinds of his dieselpunk too, determined by the outcome of the war:

Either a world in which the enemy ruling authoritarian state is a controlling force, unveiling a truly hopeless dystopian future reminiscent of Nineteen-Eighty-Four or Brazil, or the post-apocalyptic outcome seen in such movies as Six-String Samurai and Mad Max.

Or, in the words of The Flying Fortress, a society “after all the bombs have dropped.” Mad Max best exemplifies this post-apocalyptic Piecraftian dieselpunk, set in a world on the verge of collapse that survives entirely by petroleum-based technololgy.

Art on this page by Stefan Prohaczka.

2 Comments

Add YoursThe author wrote: “The Piecraftian, however, is, in the words of Piecraft himself, “more of a continual dystopian view” in the vain of George Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four.”

I believe the word should be “vein” not “vain”.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/vein

You’re quite right! Thanks for catching the typo. I’m fixing it now.