In the English-speaking world, there is a consensus about how to depict the First World War in film. It is grotty. It is dark. It is miserable. It is madness. It is absolutely, positively pointless, a tragic waste of human life from which the modern world emerged. This magazine has reviewed several films like that. None of them tried to be funny about it.

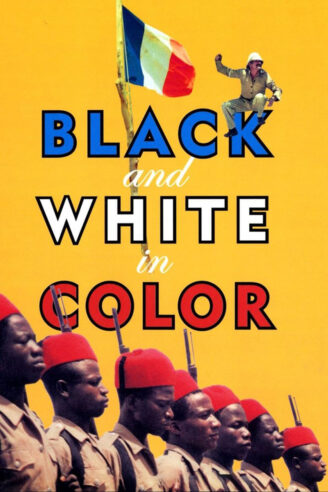

The 1976 French-Ivorian coproduction Black and White in Color (originally titled La Victoire en chantant, for a famous French war song) is different. Perhaps only the country most victimized by the war could satirize it so savagely; Paths of Glory, Stanley Kubrick’s antiwar film, wasn’t shown in France due to backlash from veterans.

Black and White in Color is set somewhere in French Equatorial Africa, near the border with an unspecified German colony (presumably Kamerun). It takes six months for news of the outbreak of hostilities in Europe to reach the French colonists at Fort Coulais. Out of love for their republic, the men of the town hastily attempt to form a small army to attack the German outpost with whom they had decent relations before the war. Right away, you get a sense of the arbitrariness of it all. Other films see it and cry out in despair. This film takes one look at it and laughs uproariously.

The force the Frenchmen form is not the Grand Armée that conquered half of Europe. It is not the force that tried in vain to withstand the Blitzkrieg. It is something that is, frankly, amusing in how pathetic it is. There is but one military man here, and despite his heroic efforts the French remain incompetent. It is a take that reminded me of Mike Nichols’ 1970 version of Catch-22, a film that turns war into farce when it was previously tragedy.

Perhaps most clever, but also the most problematic, is the film’s portrayal of Africans. Since the location of Fort Coulais is left solidly ambiguous, you never get a sense of the cultural background of the natives. Furthermore, none are named, and no individual African becomes a character in the way any of the white people are. This is countered by how they give some of the most biting commentary (shown through subtitles, not understood by the Frenchmen who aspire to be their masters) on the folly of the whole enterprise. One particularly sharp barb is directed against the French sedan chairs.

Black and White in Color is a rare film, the sort whose historical specificity complements its human universality like two peas in a pod. Pointless, deadly nonsense still occurs in great amounts today; like the film, sometimes all we can do is laugh bitterly at the whole thing.