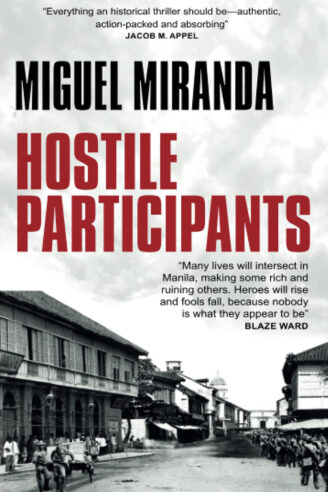

It is not obvious from my name, I am a Filipino-American. My father is white, of Scots-Irish, German, English and French descent. My mother was born in Manila. Since I was young, I was told stories of my ancestors who fought the Japanese. At times, I regret how little I read about the country, given how much I read in absolute terms. So when I was offered Miguel Miranda’s novel Hostile Participants to review, I leaped at the chance.

Hostile Participants is set during the conflict that is referred to on the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia (my hometown) as the “Philippine Insurrection.” Filipinos tend to refer to it as a crushed war of independence, an act of flagrant imperialism done in the name of access to Chinese trade and a “civilizing mission.”

This is the war Rudyard Kipling wrote The White Man’s Burden about, exhorting Americans to do to the Philippines what the British had done to so much of the world; to:

Take up the White Man's burden—

The savage wars of peace—

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch Sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

Miranda depicts this “savage war of peace” as one thing: savage. It is an apropos depiction. Much of it is spent in the backwater of Luzon, fighting in a manner that no European would consider civilized. Miranda brings a viscerality to the combat that few war novels do. It is war to the knife, fought by both sides as one that is — in their own minds, in their own ways — completely justified. It is combat done creatively, with a number of captivating scenes that take advantage of the particular setting. One involves a church, another a train.

This complex plot gives Miranda space to depict many different sorts of people in the Philippines at the time. Among the Americans alone, you have a variety of reasons for joining the military and a variety of ways of responding to what is to them a strange, alien land. On the Filipino side, you have both the poor and the ilustrados, but also a Spaniard with interesting motivations. You have a Chinese-Filipino shopkeeper with his own secrets, and two Britons for good measure.

Hostile Participants demonstrates the advantages that an organized state has in comparison to a less established government. The Americans are orderly, efficient and deadly. The Filipinos, having only a very short experience with independence, have a government that is deeply divided, and elements from within threaten its stability. This affects a central character in a painful way.

The novel also demonstrates what war does to people. The majority of the characters are soldiers, regular or otherwise, and over the course of the story they are ground down, changed by the onslaught of lead even if they aren’t felled by it. This doesn’t mean the action is downplayed, far from it; I’d place this novel about halfway between your standard thriller and Jean Lartéguy’s The Centurions (review here) in terms of action versus character.

Hostile Participants brings a forgotten war (in America, at least) to vivid life. I hope that many Westerners will read this book to learn about a country so tied up with the history of the United States and yet unknown to many. This is the war that gave the English language the word “boondock” (out-of-the-way rural area) and perhaps “gook” (a derogatory term for Asians), although that last one is disputed. Miranda has done a spectacular job of humanizing all involved, and we would all do well to read his book.