The Eastern Front of World War II is justly remembered as an exposition of the worst of humanity. It began with an undeclared invasion, was host to genocide and building-to-building combat in major cities, and ended with the largest mass rape in human history. One may be forgiven for thinking there was no decency in the “Bloodlands”, as historian Timothy Snyder called this stretch of Eastern Europe.

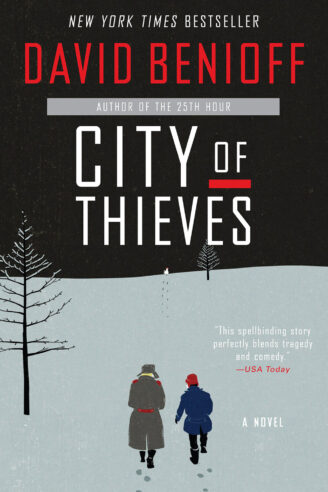

David Benioff shows there was in City of Thieves. It was inspired by tapes of the author’s grandfather, who lived through the awfulness. It is an odd thing for the Eastern Front: a coming-of-age novel with a child as its main character. There is hope, in a sense, if not for the country, then for people generally. It may be hard to swallow at first, given the madness of the surroundings, but surprisingly you come around to it.

The backdrop is the three-year Siege of Leningrad, a starvation and bombardment that killed hundreds of thousands and inspired Dmitri Shostakovich’s famous symphony. The narrator is Lev Beniov, a Jewish boy who winds up in a Soviet prison for characteristically Soviet reasons. In his cell, he meets Kolya, a student of literature, Red Army soldier and alleged deserter. The two are hauled in front of an officer who orders them to find him a dozen eggs. Given that the city is starving, this is not an easy task.

Despite taking place in the middle of what could be called an attempted genocide, the book is surprisingly funny. There is much witty banter between Lev and Kolya, as the latter has to show the former the ways of the world outside his apartment block. Kolya has a silver tongue and can talk his way into any situation. These often involve bodily functions and prostitutes, both familiar to soldiers. Lev is innocent, and Kolya takes repeated pleasure in destroying that innocence (and Lev mostly takes it in stride).

But Benioff’s refusal to sanitize war is not always funny. City of Thieves impresses in how it depicts the cruelty and depravity of how humans behave in warzones. There is one moment when Lev and Kolya stumble upon some truly ghastly doings in a Leningrad apartment. When they leave the city to further their egg hunt, they find horrors in a cabin. This does not even begin to describe their actions with the Germans or with partisans. Kolya has clearly learned to laugh when the only other option is to break down and cry.

There is a major undertone of bureaucratic lunacy in City of Thieves. Lev and Kolya are sent on their adventure (which, as someone wiser than me once said, is somebody freezing and starving to death far away from you) because of an officer’s vanity. The Kafkaesque hellscape of Soviet officialdom is on full display, and you never get the impression that the workers’ state cares about the workers it claims to defend. It is, at several points, enraging.

My only criticism is that some plot developments can be predictable to those who have read widely. There’s a particular twist that accompanies the introduction of a certain character I could see tens of pages from the end.

City of Thieves is a rollercoaster of a book. It veers widely among frustration and humor and sweetness and horror, but succeeds in balancing them all. You will feel when you read this relatively short book, and you will be glad you made the journey to a besieged, starving Leningrad.