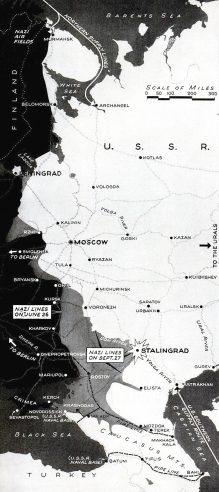

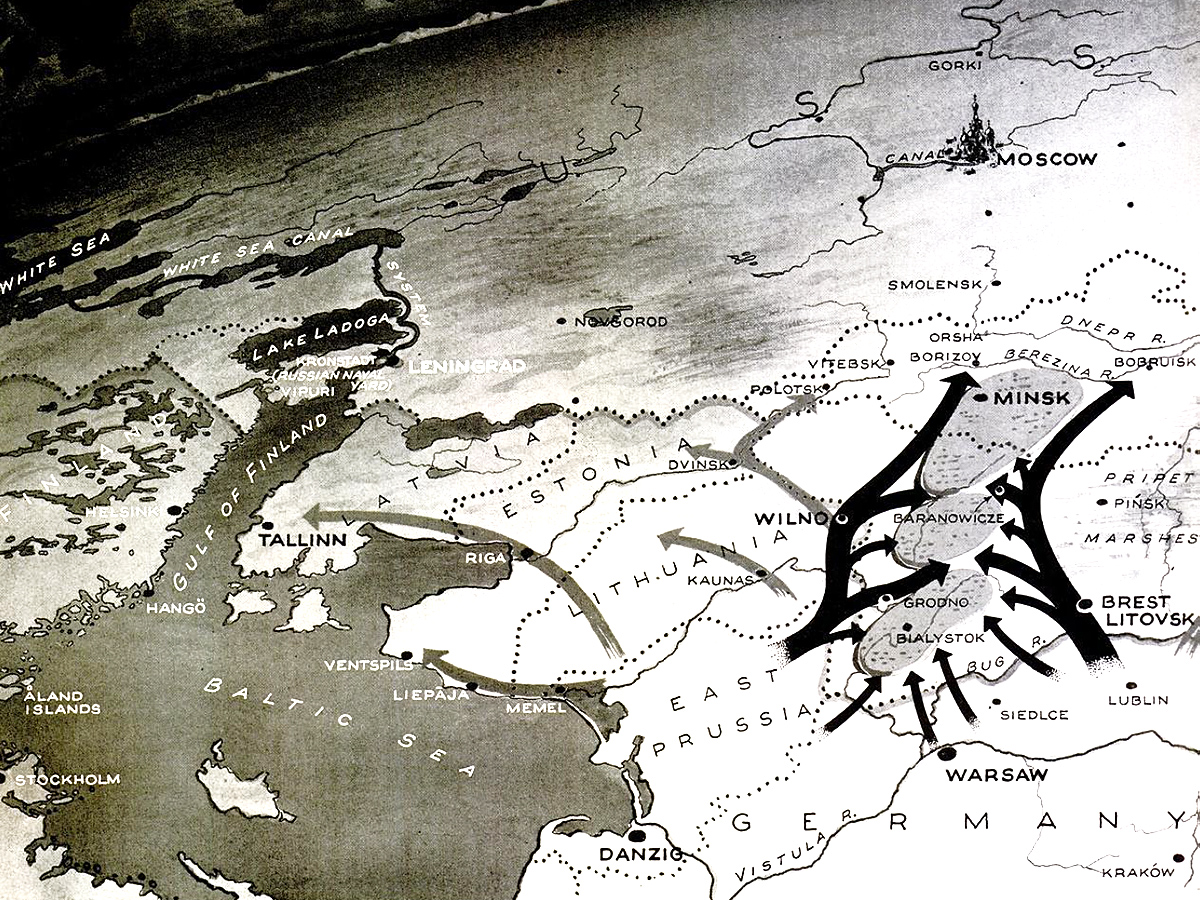

In the spring of 1942, Germany’s generals almost unanimously agreed that the Germans should renew their advance on Moscow. The Soviet counterattack in the winter of 1941-42 had pushed the Germans back somewhat from Moscow, but the Russian capital was still within German reach in the spring of 1942 — 100 miles away at one point.

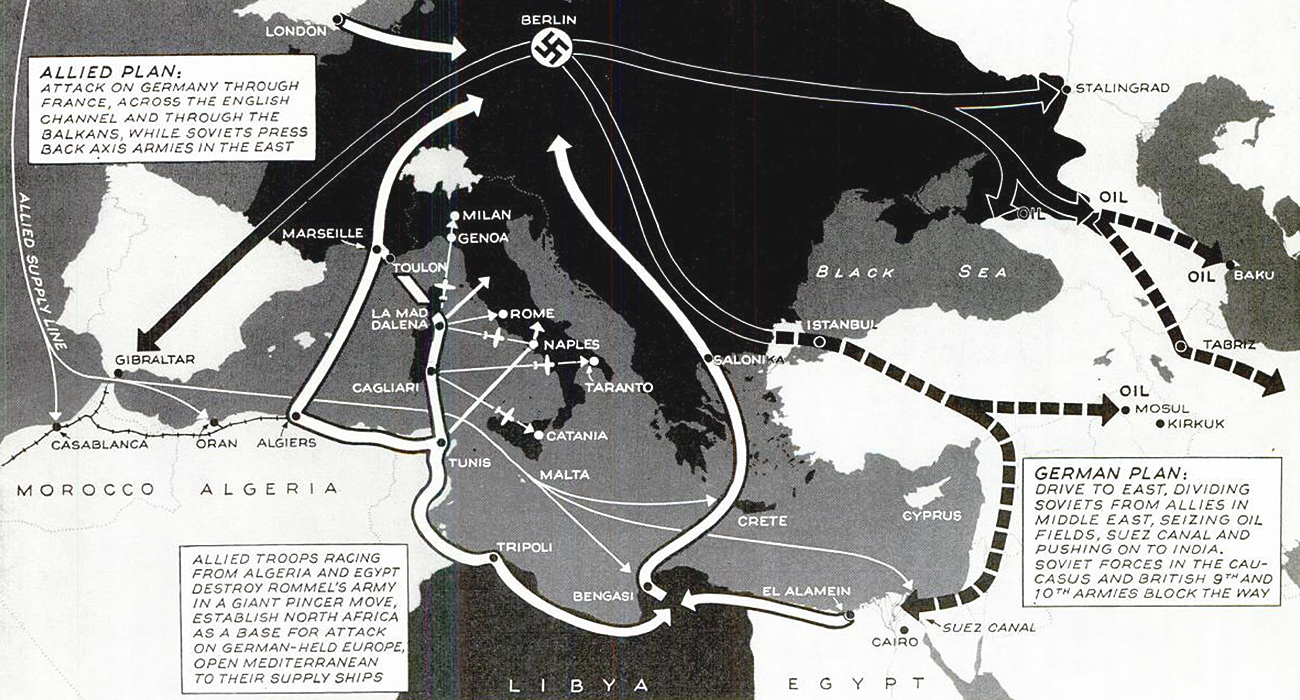

Hitler overruled his generals. The Soviets had built up formidable defenses around Moscow. They had also concentrated an enormous number of divisions there, including the bulk of their armor. Hitler decided to emphasize the southern front in a quest for oil while running a disinformation campaign to keep the Soviet forces around Moscow pinned there. The generals felt that pushing into the Caucasus without destroying the Soviet army first was like putting your head in a noose. They were proven right at Stalingrad.

What might have happened

Hitler did sometimes get attacks of common sense. They became rare as time went on, but they still happened. Let’s say he initially rejects his generals’ advice on this one. The Soviet offensive in the south is smashed and the German southern offensive starts.

Then, as in our timeline, a key German officer with knowledge of the entire plan turns up missing after a plane crash. The Germans suspect that he ended up in Russian hands. The point of divergence comes when Hitler has one of his attacks of common sense. He decides that with the southern plan probably blown, he should shift emphasis to the center. The German army concentrates on taking Moscow.

The Soviets have built up formidable defenses in front of Moscow, and they expect the Germans to go after it. On the other hand, the Soviet army is nowhere near as good as it was a year later at Kursk. The German army is still more effective man-for-man than the Soviets.

The Soviets have a lot of manpower, but it is still poorly trained and nowhere near as well armed as it was later in 1942. For example, in our timeline the Soviets built close to 8,000 T34 tanks between the end of June 1942 and December 31, 1942, along with thousands of aircraft and artillery pieces. Every month that the Soviets avoided a decisive battle made them enormously stronger.

The Western Allies are feeding the Soviets Ultra information, but the Soviets haven’t learned to trust that information yet. As a result, Soviet defenses at the point the Germans attack are nowhere near as formidable as they were for the German offensive a year later.

The Germans take heavy losses, but they break through and turn the Battle for Moscow mobile. The Soviets are better at mobile warfare than they were in 1941, but they aren’t as good as the Germans. Once the battle goes mobile, the Soviets start losing men and equipment at a prodigious rate. By early August, the Germans have surrounded Moscow and pushed the frontline nearly a hundred miles beyond it. They have killed or captured well over a million Soviet troops. They also have several hundred thousand Soviet troops trapped inside a pocket around Moscow. Many of the Soviet troops that escape do so without their heavy equipment.

Short-term consequences

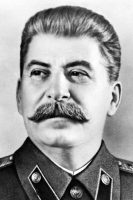

The Germans haven’t won the war just yet. Stalin and other key Soviet leaders, along with a lot of other people from Moscow and the vicinity, have escaped and gone deeper into Russia. Soviet transportation and industry are disrupted by the cutoff of Moscow, but the Soviets are cranking out new equipment at a very high rate, and new divisions are being trained and equipped almost as quickly as existing ones are destroyed.

At the same time, Stalin faces a dilemma. The troops trapped in the Moscow pocket will get weaker as time goes on. The actual fall of the capital could have a major impact on Soviet morale. Also, the Germans now control a very large part of the Russian heartland, along with a large part of the Russian population of the Soviet Union. That reduces the base Stalin has to draw on as he rebuilds his army. It also shifts the composition of that army, giving him a higher percentage of less reliable ethnic groups to draw on.

Adding to Stalin’s difficulties is the fact that Moscow is a transportation hub. The Soviet rail network becomes a lot less useful without it. Also, for morale reasons, Stalin was not able to evacuate a lot of the Kremlin bureaucracy until the last moment. As a result, many of the faceless planners that make the Soviet economy work are still trapped in the Moscow pocket. Without good communication with those planners, Soviet industry is already starting to fall into confusion. He needs to launch a counteroffensive soon. At the same time, he needs to build up a force capable of actually breaking through to Moscow.

The Germans face a different set of problems. The battle for Moscow has weakened them a lot. They aren’t getting replacement men and equipment at the rate the Russians are. As a result, the balance between them and the Soviets is no more favorable than it was in the spring of 1942. But Hitler thinks the war is essentially won. He is planning to go after the Caucasus oil starting in late August or September — as soon as Moscow falls. Fortunately for the Germans, that doesn’t happen. Stalin knows that Moscow can’t hold out until winter. The fall rains would make an October offensive very difficult. The means that the Soviets need to do an offensive with whatever they have online by mid-September. They also need help from the West.

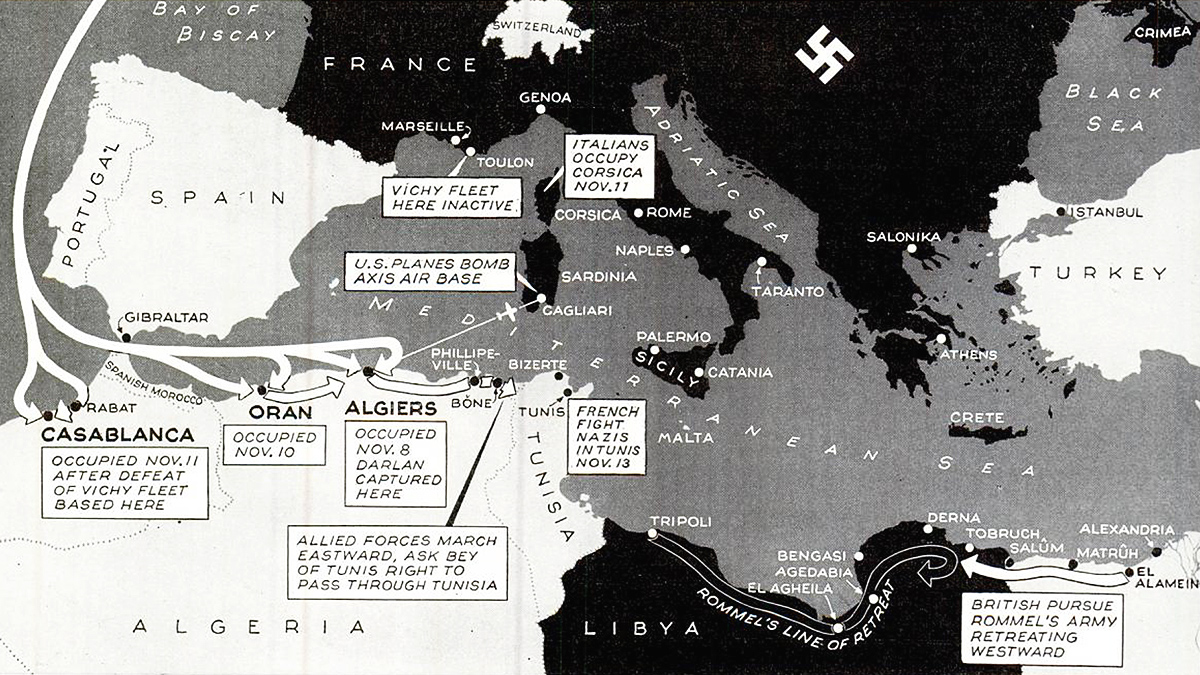

The Soviets had agreed that Operation Torch, the Allied landing in North Africa, was the route to take for the Western Allies. Now they need to either have that landing moved up or replaced by something more direct. In early July, with the battles around Moscow going badly, Stalin demands that the Western Allies move up the schedule for Operation Torch to mid-August at the latest. The British and Americans are nowhere near ready, but they throw an operation together to take pressure off the Soviets.

The result is disastrous. The British have not yet broken the German navy’s version of Ultra. The U-boats are still a major force in the Atlantic. They sink or scatter a major hunk of the American part of the invasion force with tens of thousands of casualties. Some damaged American troopships make it to French ports in North Africa, but are in no position to launch an invasion. The French intern them, quietly adding some of their equipment to clandestine stockpiles that the Vichy regime is accumulating in North Africa. The British part of the force arrives relatively intact, but the Vichy French in North Africa are aware of the US disaster. They understand which way the wind is blowing and fight to repel the British invasion. The Brits alone are not able to win against determined French resistance. They are forced to evacuate with heavy casualties.

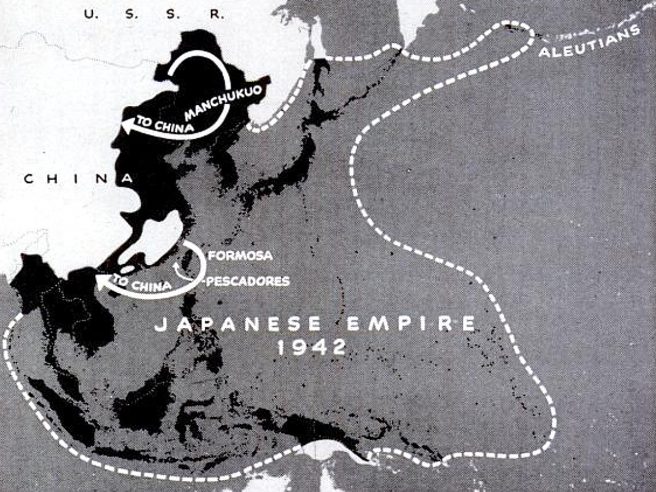

Hitler is confirmed in his low opinion of British and American fighting ability. He pulls more troops from garrison duty in the west and puts them into the fight in Russia. Stalin is furious. He demands a big increase in aid or an immediate attack into France. Neither the Americans nor the British are in a position to do either of those things until they get the U-boats under control and reequip their armies. The strong Asia-first group in the American military now pushes for more resources. They argue that it is important to finish off the Japanese before the Germans finish off the Soviets. American victory in the Battle of Midway has made victory over the Japanese look possible. The defeat of the Torch convoy convinces many people that the US is not ready to take on the Germans yet. They argue that putting more pressure on the Japanese will actually help the Soviets more than a second front would by keeping the Japanese from attacking the Soviets from Manchuria.

The Roosevelt Administration wants to keep the focus on Germany, but they also need a victory to distract attention from the Torch disaster. It looks like the Torch sinkings are going to cost the Democrats dearly in the midterm congressional elections. Churchill also needs a political boost. Japan offers much more near-term potential for that than Germany does. But where should the allies put their strength? Burma? New Guinea?

Roosevelt pushes for a major commitment to Burma. He thinks that a victory there may open up a land route to Nationalist China, who can then be brought up to strength by US weapons so that they can take on the Japanese, who hopefully will then be too busy in China to attack the Soviets in their time of weakness. The British are able to move some troops to Burma that in our timeline would have gone to the Middle East to counter a possible German breakthrough from the Caucasus. The Burma offensive is not massive. The Allied logistical base there is too flimsy. It does yield some progress, but not a breakthrough to link up with the Nationalist Chinese.

Hitler is delighted by Vichy France’s resistance to the British landing. He has been dreaming of making the Vichy French a minor German ally. He has been authorizing small-scale reequipping of the French armed forces already. For example, in our timeline he allowed the Vichy French to produce a few hundred Dewoitine fighter planes for their air force in 1942. He cautiously expands that program. He allows the French to modernize a few hundred tanks that they have allowed to keep in North Africa and to produce a few new tanks to replace the ones which were destroyed in the attempted British invasion.

The Vichy French use the modernization program as a way to explore new vehicle designs (in our timeline the French continued clandestine tank design through the German occupation). Those design efforts focus mainly on up-gunning late models in the prewar S35 and H35 lines, and making turret less self-propelled guns based on them. There are also efforts to design a new vehicle based on the B1 tank series, but with a long barreled 75mm gun in the turret instead of a 45mm gun there and a short-barreled 75mm gun mounted in the hull. The Be upgrade project remains under the table, but it is helped by the open projects.

The Vichy French also push the Germans for release of some of the two million-odd French prisoners of war that the Germans are still holding. Hitler likes the leverage that those prisoners give him over France, but he also wants to lure Vichy France deeper into collaboration. Some hard negotiations leads to a compromise. On a voluntary basis, French prisoners of war can do six months of occupation duty in the southern part of the Soviet Union (Ukraine). After that they can go home.

The Germans have already recruited several thousand individual Frenchmen to serve in various German units on the Eastern Front. The new units will be nominally under French command, though the Germans maintain tight control of the chain of command at the higher levels. Collaborationist factions of the Vichy government like the agreement for obvious reasons. Factions in the government that want to eventually bring France back into the war on the Allied side go along with it, because it will give France a pool of trained fighting men to draw on if France does reenter the war. The Vichy army in France itself is officially tightly restricted in terms of tanks and heavy artillery. As Vichy maintains a small army on the Eastern Front, there always seems to be a substantial amount of heavy equipment either awaiting repairs or awaiting shipment to those troops. That may or may not become important later.

Hitler is reluctant to get the Vichy French involved in the Soviet Union, but with the additional territory he has seized in Russia he desperately needs more anti-partisan units. The French end up with close to 100,000 men in the Ukraine. The Germans quickly become annoyed because those troops, like the Hungarians in our timeline, develop a close relationship with Ukrainian nationalist groups, like the Ukrainian People’s Army. Those nationalist groups are attacking German supply lines in other areas — not because they are pro-Stalin, but because stupid Nazi racial policies have given them no choice. The French also smuggle some weapons to the Polish underground.

In the wake of the Torch fiasco, Stalin pursues two tracks. First he tries for a negotiated settlement with the Germans. Second, he frantically builds up reserves for a mid-September offensive to link up with Moscow. His generals advise against that offensive. The new divisions will not be fully equipped or trained until late October at best. The situation in the Moscow pocket can’t wait that long though. Civilians who are not essential to the defense effort are starving in droves. Defense production is continuing, but that can’t last forever. Eventually raw materials will run out. Then it will just be a matter of time before the Russian divisions in the pocket run out of bullets. They are already on very tight rations, both in food and in ammunition. Small-scale airdrops help some, but the Germans control the skies over Moscow and the Soviets know they can’t supply their army by air.

The Western Allies do everything they can to distract the Germans short of a second front. The British push an offensive in North Africa. They increase their bombing. They launch a series of pinprick raids on the French and Norwegian coasts. They increase aid to partisans in France. With the desperate situation in Moscow, Stalin allows the US to base bombers in Russia for airdrops and to help support the Soviets on the ground.

The main Allied effort is against Japan, though. As I mentioned earlier, the Allies launch an offensive in Burma, with both US and British forces playing a role. That’s intended to draw Japanese troops away from Manchuria, which in turn will allow the Soviets to move divisions away from the Manchurian border. US troops are also accumulating in England. No second front is planned until 1943 at the earliest, but at least they keep the Germans from moving even more combat power to the Eastern Front.

The Soviets launch their offensive in early September. At first it does well. The Soviets have a lot of T34s and a lot of brave, though poorly trained, infantry. The Germans have depleted a lot of their combat power in the battles around Moscow.

Stalin pushes the French Communist Party into a premature and essentially suicidal revolt against the Germans. The revolt does tie up German divisions which could otherwise have joined the fight around Moscow. Essentially, Stalin sacrifices a pawn. He hopes that the Western Allies will feel obligated to jump in and help the French Communists. They do to the extent they can, with airdrops and ground support bombing, but the Communists are crushed.

In Russia, the Germans are pushed back, but Soviet losses are far too high to sustain. They lose over half a million men before the fall rains turn the battlefield into a giant swamp. The Germans lose less than a fifth of that, but they are still shocked at the number of casualties they take.

Even with less territory to draw on, the Soviets still have a huge capacity to replace their losses. Between their own production and US and British aid, the Soviets can build new armies quickly. They just need time to train the people in those armies to the point where they are more than just cannon fodder for the Germans. Up until at least late 1943, the Soviets get stronger any time they are not losing men and equipment at several times the German rate.

Through September and October, the Moscow pocket shrinks. American and British bombers and transports are doing what they can to keep the pocket supplied from Soviet airfields. They are also losing a lot of aircraft and crew. The Germans ring the pocket with anti-aircraft guns and go after the bombers with fighter planes. They also bomb the airfields that the allied planes are based on. Stalin hopes to resume the offensive by mid-October. Rain keep falling until the end of October. By that time the Moscow pocket is crumbling. People are starving. Soldiers are running out of ammunition. When it becomes obvious that Moscow will fall, secret police systematically destroy or boobytrap everything of value in the city.

The Germans are not eager to get into a house-to-house fight in the city, so they gradually and cautiously move into the ruins. Some Soviet troops surrender. Others try to break out and join the partisans. Several thousand lurk in the ruins, staging hit-and-run raids on the Germans. The Germans take the ruins of some of the major symbolic buildings, but are in no hurry to clean up the rest of the pocket. There are still several million civilians in the remnants of Moscow. Most of them are nearly dead from starvation. Hitler decides to let them die in the pocket.

Once the Soviet troops in the pocket become militarily insignificant, Stalin is no longer interested. His propaganda machine emphasizes that Russians destroyed Moscow to deny it to the invaders, just as they did when Napoleon invaded. The Soviets do some small offensives in the south, mainly against Italian and Romanian troops, but they mainly work to build up their forces for a late-winter offensive.

Unfortunately for them, war production goes into a tailspin, as raw materials in the pipeline are used up and the disrupted central planning process and the disrupted rail system fail to get enough of the right stuff to the right place at the right time. By German standards, Soviet production is still very high, but it is much lower than in our timeline. Between battlefield losses and lower production, the Soviets have less than one-third the number of T34 tanks at the end of 1942 in this timeline that they had at the same time in ours. Other weapons numbers are comparable. The worst of the disruption is temporary, but it leaves the Soviet army incapable of launching a major offensive in late 1942 or early 1943.

At the end of 1942, the Germans think that they are seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. They are wrong. The Soviet Union lost over a million men killed or captured in the second half of 1942 in our timeline, and still ended the year with a larger, more effective army than they had in June 1942. In this timeline, the Soviet army has actually shrunk a little from mid-1942 levels, and is nowhere near as well equipped, but it is still formidable with well over four million men at the front and several thousand reasonably modern tanks.

Medium-term consequences

Early 1943, Eastern Front

The Germans launch an offensive for the Caucasus oil in spring 1943. They make good progress. The Soviets can trade space for time, and they do. The Germans have better logistics once they get the captured Soviet rail system working for them.

Unfortunately for them, Soviet production starts going back up again. The central planning system gradually gets put back together. By mid-1943, the Soviets are back to 70 percent of their production prior to the fall of Moscow. The Soviets regain their resilience. Stalin has also learned to take the advice of his generals. He isn’t throwing away manpower on premature offensives and hopeless defenses. Hitler never learns this, and actually intrudes more and more as the war goes on. At some point late in 1943, he pushes the German army into trying for one victory more than it can give him. I’ll deal with the details of that later. Then the Soviets start to retake their territory. That process is a lot slower than in our timeline, because:

Early 1943, Southern Front

Without the Torch landings in North Africa, and without the German defeat at Stalingrad, the Italians probably stay in the war longer. If Italy stays in the war, the Germans can commit to Russia the 25 divisions they had to commit to Italy in our timeline, plus the troops they had to commit to the Balkans to fill the gaps left by the Italian surrender.

Also on the Southern Front, in early 1943 the Germans and Italians are cornered in Western Libya with their backs to the border of French-held Tunisia. The Germans pressure Vichy France to allow Germany to use Tunisian ports to supply their army in North Africa. The Vichy French have been trying to preserve what is left of their neutrality after the failure of the Torch landings. They don’t want to get sucked into the war again, especially not on the German side.

Some Vichy officials have been quietly sounding out the Americans, trying to figure out how much help they would be able to count on if they defy Hitler. In early 1943, they can’t count on much. The US is still trying to win the war against the U-boats so that it can project power. The Vichy French reluctantly allow resupply of the German force in North Africa through their ports. Vichy France and the US still have diplomatic relations. The US puts enormous pressure on the French to stop the supplies. The French want guarantees that a US force will land in France if Vichy cuts off the supplies and Hitler retaliates against them. The US is not quite ready to give that assurance.

In late June 1943, a new crisis arises. The Germans and Italians are pushed back into Tunisia, but they refuse to be interned. The British pursue them and the Vichy French are cornered. They have to choose sides. It’s a finger-to-the-wind-type situation. The Vichy are divided. They want France to come out on the winning side, but at this point they aren’t sure which side that is. They know that German power is declining compared to the US and Britain. They know that the British have overwhelming superiority in North Africa. They know that US forces are building up in England for an invasion of France. They stall. They pressure Hitler to allow them to build up their North African army more. They pressure the United States to commit to specific actions on a specific timetable if Hitler invades the unoccupied third of France.

The British start taking over administration of Tunisia, and make it clear that France will lose its colonies permanently unless Vichy moves quickly to take sides. The Free French under de Gaulle are furious about that. They recruit in the British occupied areas and build up their forces. The Vichy French almost get in a shooting war with the Free French.

Early 1943, Western Front

The Americans don’t get combat experience against the Germans in 1942 or early 1943. They want to go directly to an attack across France in 1943. The British strongly disagree. They want to follow up their victory in North Africa with an attack on Italy. They don’t have the strength to do that on their own. The US is not interested in getting dragged into what its leaders consider a sideshow. The British do convince them to commit a division to North Africa to gain experience at fighting the Germans. The British intend that as an opening wedge to get the US committed to the Mediterranean. The US goes along with it to gain experience. That proves wise. The inexperienced US troops are given a very rough introduction to modern warfare by the Germans in North Africa.

Late 1943, Southern Front

The debate between advocates of a southern strategy and a thrust into northern France goes on as US forces gradually build up in England. By mid-1943, an invasion of France is theoretically possible. The situation in North Africa and the Soviet Union makes it urgent. The Vichy French know that Hitler will try to take the unoccupied southern part of France if they defy him in North Africa. Now the US is in a position to assure them that they will get help against Hitler if he goes after southern France. The US has pushed the British into agreeing to a cross-Channel invasion, supplemented by a British landing in southern France if Hitler goes after Vichy. That is a compromise. The British don’t want a cross-Channel invasion in 1943 under any circumstances. The Americans want one in 1943 whether or not the Germans invade Vichy France.

The Vichy French officially have 100,000 men under arms, with essentially no armor, very little artillery and very little transportation. They have some planes, but not many. Off the books, they are in much better shape. In our timeline, the French had a secret plan to mobilize enough reservists to bring their army up to 300,000, and to mobilize a fleet of trucks for transport. They also built hundreds of unarmored versions of a tracked personnel carrier and sold them as “forestry tractors”. They kept track to those “tractors” and retrieved all but one of them for the resistance in 1944. They also built and stashed armor for those “tractors”. They even hid planes and artillery. They also ran a large-scale outdoor survival training program for unemployed French young men — not military training, just a much tougher version of the boy scouts. That toughened the young men up and would have cut down the time needed to turn them into soldiers.

In this timeline, they also plan to mobilize tens of thousands of additional French troops who have returned from occupation duty in Ukraine. They also have a couple hundred tanks or self-propelled guns which are officially being repaired or awaiting shipment to North Africa or Russia. Even with those men, and with the tanks and artillery they have clandestinely built up, they are obviously no match for the Germans on their own.

Negotiations between Vichy officials and the US drag into early August. The Germans become aware of them, but Hitler waits for about a month before taking action. The Germans are in a crucial phase in the East. It looks possible for them to break through the Caucasus Mountains into the Middle East and attack the English from the rear.

As August and then September wears on, it becomes increasingly obvious that the Western Front is going to require attention. The Soviets are putting more and more pressure on the Western Allies to do a second front. The American build-up in England is becoming more ominous. It doesn’t look as though the German and Italian troops in North Africa will hold out much longer. The Germans begin moving troops into position to take over Vichy France, and possibly to go through Spain into Morocco to support their troops in North Africa. The US and British are aware of those moves because of Ultra. They already have contingency plans for a British landing in southern France and Corsica, along with a mainly-American cross-Channel invasion.

In mid-September 1943, Hitler rolls south into unoccupied France with about eight divisions — not very high-quality ones at that. The Italian army invades from the east with about six divisions. The Vichy army deploys to protect some reasonably defensible positions. The Germans for the most part bypass them and head on toward the ports of southern France, trying to take those ports before the British land. The Vichy French concentrate some of their best forces and most of their hidden equipment around the southern ports. The British land in Corsica at the same time the Italians land a force there. The Italians are quickly defeated in Corsica. The French hold onto some key ports in southern France long enough for the British to land.

The Germans timed their invasion so that it would take place at a very unfavorable time for an Allied cross-Channel attack. The weather that time of year would make any landing hazardous and make the following build-up of Allied forces difficult. The force invading southern France is a substantial percentage of their total combat power in France. It includes nearly all of their mobile forces. Hitler is gambling that he can beat the French and British in the south of France, then get the mobile forces back in time to defeat any American cross-Channel invasion — all without taking resources away from the Eastern Front.

That doesn’t work. The German Panzers get a nasty surprise around the southern ports as they run into French armor. The French have taken a prewar design called the SAU40, a turret less self-propelled artillery version of the SOMUA S-35, and mated it with a French 75mm anti-aircraft gun. The resulting vehicle has somewhat more firepower than a German Panzer IV, though a lot less than a Tiger I or one of the new Panthers that are just entering German service (later than in our timeline because there is none of the urgency generated by the Stalingrad defeat). Against second-rate German divisions and their second-rate tanks, the French do fairly well, holding out long enough for the British to lodge themselves securely in several southern ports.

Marshal Pétain, head of Vichy France, purges his government of the worst of the collaborators and urges Frenchmen to unite in a fight against the Germans. He is still popular because of his role in World War I, and most Frenchmen go along with him. Some pro-German Vichy politicians flee to the Germans and try to get the Germans to recognize them as the real French government.

In North Africa, the Vichy French join the fight against the Germans and the Italians. That fight doesn’t last much longer. The Allies have control of the air and use it to cut the already tenuous supply lines from Italy to North Africa. The last Axis troops in North Africa surrender less than a week after Germany invades Vichy France. That frees up British and French forces for the fight for southern France. By mid-October, the British have built up enough to break out of the ports and link up, controlling the bulk of the coast of southern France.

The Germans are now paying a price for bypassing the Vichy French on their way to the coast. American planes and French forces are making it very difficult for the Germans to get supplies to their forces in southern France. As the Germans concentrate on the British and French troops in southern France, the Vichy French launch several surprise attacks north from bypassed pockets into occupied France. Those attacks are devastatingly effective because the French are facing third-rate occupation forces — more a police force than an army — and those forces are deployed against an internal threat rather than a real army. The attacks overrun German-held airfields, capturing or destroying planes intended to support the German effort in southern France. They also overrun supply depots supplying the forces in southern France. Those attacks threaten to close the supply routes to Southern France.

The British now outnumber the Germans facing them by a substantial margin. They break through German lines and head north, threatening to cut off the entire German force facing them. The allies now have control of the air in southern France, while the Germans are fighting on a logistics shoestring. The Germans are also trying desperately to keep what supply lines they have left from being cut by the Vichy French. The British attack catches the Italians on the southern side of a Vichy French pocket from the rear. The British cut through and link up with the Vichy pocket, then send armor through it, cutting the Germans off in southern France. By the end of 1943, almost all of Vichy France, plus a substantial part of France north of the occupation line are in allied hands. By this time though, the Germans have moved substantial first-rate forces from the eastern front and are preparing an offensive to link up with their cut-off forces and retake southern France.

Late 1943, Western Front

Meanwhile, the Americans are getting ready for the cross-Channel invasion. The British have stalled until it’s really too late in the year for that, but the Americans think that a unique opportunity is slipping by. They have options for a full-scale invasion and also for a series of large-scale raids to tie down German troops. The Americans are also using the airlift expertise that they built up in the attempt to save Moscow. Substantial Vichy French forces have been bypassed by the Germans in their rush to the sea. Those forces have now regrouped. They still control the bulk of southern France, including several airports. The Americans are rushing supplies to them: artillery, jeeps, bazookas, machine guns and ammunition, even a few light tanks. An American airborne division lands in one of the pockets. American fighters fly into some of the French-held airports and begin air support operations.

The British are still dragging their feet on a cross-Channel invasion. They feel that the threat of an invasion ties down as many German troops as an actual invasion does, without the risks. That argument loses force as the Germans move more forces south to deal with the British and the Vichy French. The Germans are gambling. They have actually taken a few of the Caucasus oilfields, and are tantalizingly close to the major ones. Hitler wants those oilfields badly enough to risk making a cross-Channel invasion easy. He pushes the Italians to send more troops into the battle for southern France, pitting them against the Vichy French pockets while sending more German troops from northern France into the battle against the British around the southern ports. When the French attack north out of the bypassed pockets, the Germans pull more troops out of the coastal defenses to contend with those attacks.

The Americans and British launch a coordinated series of large scale raids across the Channel: larger versions of Dieppe Raid. German opposition is surprisingly light and the Americans quickly take advantage of the situation to expand their objectives to taking and holding a port. That proves harder than it looked. Hitler is now shifting substantial forces from the Eastern Front to France. By the end of 1943, the US has a fragile lodging on the coast of France. US forces there are getting their first taste of what a first-class German force is still capable of.

Late 1943 in the East

In the East, the Germans are doing the same thing they did in 1942 in our timeline: going for the Caucasus oil. They are in a much better position to do so than they were in our timeline. They don’t have the long, exposed northern flank to deal with, because they have already taken more territory to the north. At the same time, the Soviets have built up their forces again. They have an amazing resilience, because they are building tanks and planes and artillery at such a high rate. The Western Allies fill in any gaps, sending hundreds of thousands of trucks, millions of boots and uniforms, and large amounts of canned food.

The Germans get somewhat further than they did in 1942 in our timeline. They actually take and hold some of the oilfields. Hitler thinks that they are almost in a position to knock the Soviets out of the war. The last pockets of resistance in Moscow have long since been starved out. Leningrad hasn’t fallen, but it is getting weaker and weaker as the summer of 1943 wears on and the Soviets are unable to create a corridor through the surrounding Germans. (They blasted a narrow corridor through to the city in our timeline.) They are transporting some food and raw materials across Lake Ladoga to Leningrad, but nowhere near enough.

The Soviets are nowhere near out of the war, though. In late 1943, Hitler is forced by events in France to go over onto the defensive without quite reaching his objectives. That actually turns out to be a good thing for the Germans. The Soviets have prepared a winter offensive that might have trapped the entire Army Group South if the German offensive had gone on much longer. As it is, the Germans find themselves switching desperately needed forces that had just gone into action in France back to the Eastern Front to avoid a complete disaster there.

There is also a sideshow in the East. When Hitler goes after Vichy France, he attempts to disarm the Vichy French contingent in the Ukraine and return them to prisoner-of-war status. That does not entirely work. The French turn over anything they can’t move quickly to the Ukrainian nationalists and head toward the Romanian border. Some French troops stay and fight with the Ukrainians. Some are captured. Around two-thirds of them make it to Romania. Romania is officially allied with Germany. They are also traditional allies of France. The Romanian government “interns” the French but refuses to turn them over to the Germans. Hitler is furious, but he needs the Romanians, so he allows the decision to stand.

1943 in the Pacific

The emphasis on Burma that started in late 1942 is now paying off. The Japanese have been pushed out of enough of Burma that it looks like early 1944 may see a reopening of the Burma road. That in turn would allow a major reequipping of the Nationalist Chinese Army.

How plausible is this so far?

Alternate histories inevitably get less and less plausible as they get further from the point of divergence. There are so many forks in the road of history. Without reality to guide you, how can you know that you are taking the right one? This alternate history has gone out about a year and a half so far. There are already a number of forks in it where things could easily go a different direction than the one I describe.

For example:

Could the Germans really have cut Moscow off in summer 1942 and kept it cut-off?

I don’t know. There were an awful lot of Soviets to go through. They weren’t as good as the Soviets of July 1943, or even as good as the Soviets of November 1942, but they were better than the Soviets of summer 1941. The Germans did very well against the 1942 Soviets essentially everywhere except at Stalingrad. On the other hand, the Soviets concentrated their best forces and commanders around Moscow. It would have been one incredible battle. I wouldn’t mind seeing it war-gamed sometime.

Would Hitler have resisted the temptation to get into a street-by-street fight for Moscow?

He did in Leningrad. He didn’t in Stalingrad. I’m guessing he would in Moscow, but anyone who says they can predict Hitler’s actions in an alternate-history situation is being rather optimistic.

Would the U-boat disaster to Operation Torch have happened?

Probably not. The Allies probably would have just done some raids on the French or Norwegian coast, then tried Operation Torch on schedule. On the other hand, people make mistakes in real history. This isn’t the most likely outcome, but it is not all that farfetched.

With Moscow about to fall, Operation Torch would have had problems in any case. The Vichy French were a mixture of genuine fascists, opportunists who just wanted to be on the winning side, and French patriots who wanted to make sure France made it through the war and reemerged as a great power. All of those factions would be much less inclined to go along with an Allied invasion of North Africa if it looked like the Soviets were about ready to go down. The impending fall of Moscow would have made a lot of people think that.

Would the US really concentrate more effort on the Burma area in 1942?

Maybe. It depends on how the interallied politics and the US domestic politics plays out in the aftermath of the failure of the Torch invasion. It wouldn’t have been a bad strategy. Opening up a land link to Nationalist China and reequipping its army would have done a lot of very nice things for the Allies. It would have also had some interesting postwar implications.

Would the US really have held off on a cross-Channel invasion through 1942 and most of 1943?

That depends on how much impact the failure of the Torch invasion had on US decisionmakers.

The British really didn’t want to go that route, and they would have had a major impact on decision-making until US military power eclipsed theirs in late 1943.

This story was originally published on Dale’s website in March 1998.