Sometimes I think it was a miracle that the American civil rights movement didn’t lead to open civil war. We remember the resistance as nonviolent, but there certainly was violence, the 1963 Birmingham Baptist Church bombing being an infamous example.

Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered for advocating nonviolence. Not all African Americans agreed with him. Malcolm X called King and his followers “hand-cuffed by the disarming philosophy of nonviolence” in a letter to George Lincoln Rockwell, the head of the American Nazi Party, on the eve of the March on Washington.

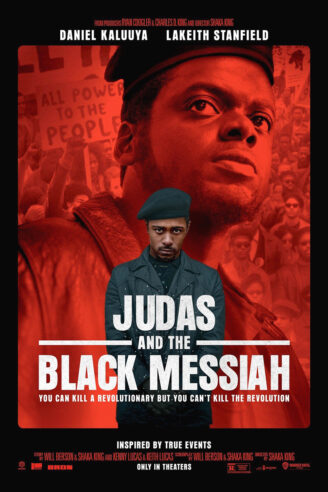

Opposition to nonviolence was a reaction to the violence inflicted upon black Americans by police and organizations like the Ku Klux Klan. One group that wasn’t afraid to take up arms was the Black Panther Party, and it is the subject of the award-winning Judas and the Black Messiah.

The film is a conflict between the brutality of Chicago society (King had called it the most segregated city in America) and a group of hardened, idealistic men and women devoted to equality and justice. A less courageous picture might have reduced them to peaceniks with the occasional gun shown, advocating for African Americans alone. Judas and the Black Messiah shows all sides of their activism, from running kitchens and hospitals for the needy to making inroads with other groups, like Puerto Ricans and poor whites, to make common cause against police brutality.

The standout performance of the film is Daniel Kaluuya as Fred Hampton, the leader of the Black Panther Party in Illinois. He is the ideal revolutionary: kind to the vulnerable, firm and unyielding toward his oppressors, and deeply knowledgeable about the means to bring about change. Kaluuya brings not only a hardness but also a vulnerability to the role. His Hampton is a man who has very human feelings about his friends and a quiet anxiety from his role as a mover and shaker. It is a performance that makes the inevitable conclusion all the more painful.

Kaluuya is flanked by Lakeith Stanfield as Bill O’Neill, the FBI informant in the party who ultimately brings it down. Stanfield brings out the internal struggle of a man who must choose between what he believes is right and what benefits him materially. He is a reluctant quisling, and a compellingly rendered one.

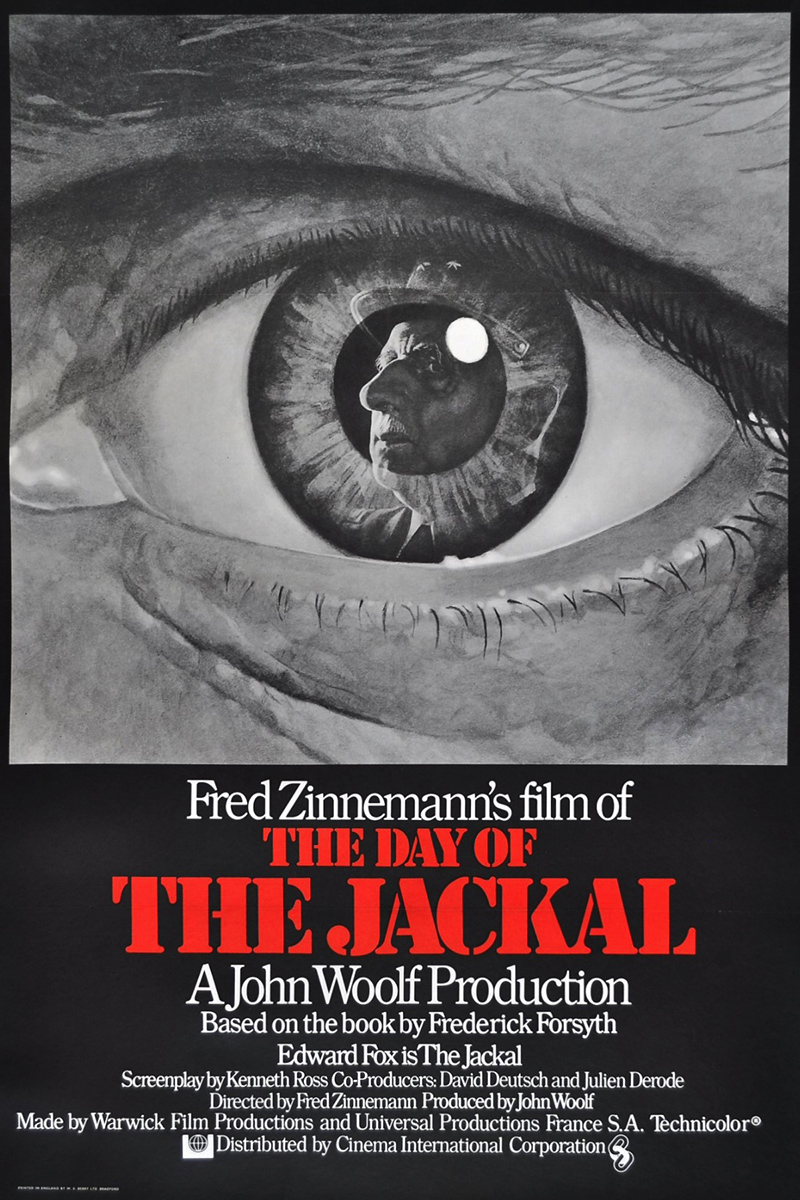

Judas and the Black Messiah can be compared to Der Baader-Meinhof Komplex (review here) and Bloody Sunday (here). All three movies revolve around the violence that a modern liberal democracy is willing to inflict on its internal enemies. The Black Panthers may have been more moral and more practical than West Germany’s Red Army Faction; the similarities are in the breakneck portrayals of urban guerrillas fighting a state that calls itself just and is willing to kill to maintain that justice. Like Bloody Sunday, it ends with the violence that underpins all states by virtue of their monopoly on violence. It is a poignant film about a neglected chapter in American history, one for which the accolades are entirely deserved.