Many of us in the Western world might think of Southeast Asia as a dense jungle where white people go to die. The French and the Americans died in Vietnam. The Dutch died in Indonesia. The British died in Malaya.

The Philippines are often overlooked. Americans may remember the islands played a role in World War II. They will speak of Corregidor (properly with a rolled “r” and a “g” pronounced like an “h” — it’s a Spanish word) and Bataan (a three-syllable word) and Leyte Gulf. What they may not remember is the war that gained Americans the Philippines, and the empire that ruled it before them.

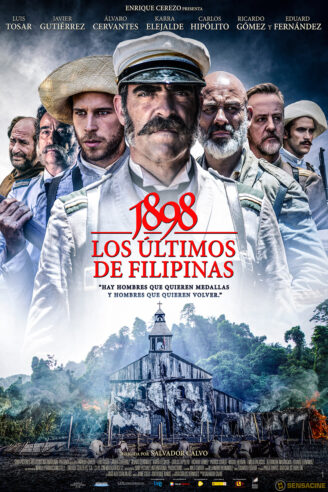

That empire was Spain. Spaniards arrived in the archipelago four centuries before the Americans threw them out by concocting an espionage scandal out of a boiler accident. 1898, Los últimos de Filipinas, released in the English-speaking world as 1898: Our Last Men in the Philippines, is about the end of that war.

I must disclose a personal interest in the film: I am an American of Filipino descent through my mother. Both my grandparents on that side were children during the Japanese occupation. As such, I am interested in seeing cinematic portrayals of the wars of that country, as well as how they treat the Filipinos.

This is an unambiguously Spanish film. Viewers hoping for a valiant tale of Filipino resistance to colonialism will be disappointed. The main characters are all Spanish soldiers who have been deployed to the islands as the twilight of the Spanish Empire draws closer. They hold up in a church in Baler, on the coast of Luzon, where they have to withstand the assault of the Katipunan, the Filipino resistance.

They stay in the church far longer than they need to on the order of Lieutenant Martín Cerezo, given a gripping portrayal by Luis Tosar. Even when news arrives that the war is over, and the Philippines have become American territory, he refuses to let his men surrender and leave the church. Under his command, disease prospers and men die needlessly. He is balanced by others soldiers, as well as a priest and a medic, who act as the reasonable people in an environment strangled by an officer’s unreason.

Those wary of a film that mistreats the Filipinos can be reassured. The Katipunan fighters and residents of Baler struck me as the more reasonable side. They ask the Spaniards why they fight an awful war and suffer debilitating illness for a government that seems willing to let them die forgotten, and Lieutenant Cerezo cannot furnish a good answer. The Filipinos are the ones who see what human dignity is while Cerezo will sacrifice that of his men to preserve his own.

1898 is a film about duty. The blistering charnel house bound by church walls seems to speak to how it is not always sweet or fitting to die for one’s country. Arguably, it gives more nuance, for the men seem to die less for Spain and more for Lieutenant Cerezo. It shows the great bluff that is imperialism as they die ingloriously abroad for nothing. It is a powerful film about savage wars of peace, and worth watching for that reason.