Fear of communist infiltration in the United States preceded the Cold War. So-called “popular fronts” — anti-fascist and anti-imperialist — were active in the 1930s and attracted various well-meaning progressives. As Hugh Wilford puts it in The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America (2008), everyone from the “Jewish fur-worker dismayed by the rise of anti-Semitism in Hitler’s Germany” to the “student inspired by the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War” to the “African American protesting Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia.” Support for the Soviet Union was usually far down their list of priorities, but Soviet influence, and Soviet money, nevertheless played a role.

After the Second World War, Moscow played up its efforts to spread communism abroad. It focused primarily on Europe (France and Italy had large Communist parties) and the Third World.

In the United States, the Central Intelligence Agency was created amid the Red Scare and tasked with countering Soviet subversion.

Psychological warfare

William Donovan, wartime chief of the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, believed persuasion, penetration and intimidation were “the modern counterparts of sapping and mining in the siege warfare of former days.” His OSS had a division devoted to Moral Operations, which tried to suggest widespread demoralization among ordinary Germans and Japanese.

In December 1947, CIA was called on to do something similar. A memorandum circulated to members of the newly-created National Security Council that month warned that the Soviet Union was,

conducting an intensive propaganda campaign directed primarily against the US … employing coordinated psychological, political and economic measures designed to undermine non-communist elements in all countries.

The goal of this campaign, the memo argued, was to undermine American prestige and divide world opinion “to a point where effective opposition to Soviet designs is no longer attainable by political, economic or military means.”

In conducting this campaign, the USSR is utilizing all measures available to it through satellite regimes, Communist parties and organizations susceptible to communist influence.

America didn’t have a specialized agency to resist this propaganda campaign. So it fell to CIA to initiate “covert psychological operations” against the Soviet Union and communism around the world.

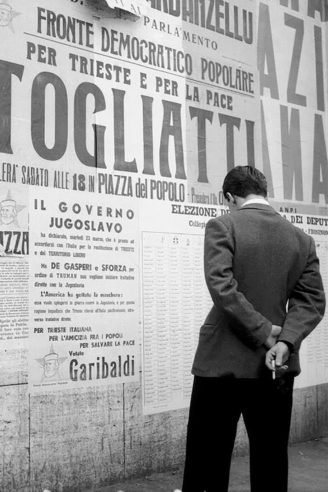

Learning in Italy

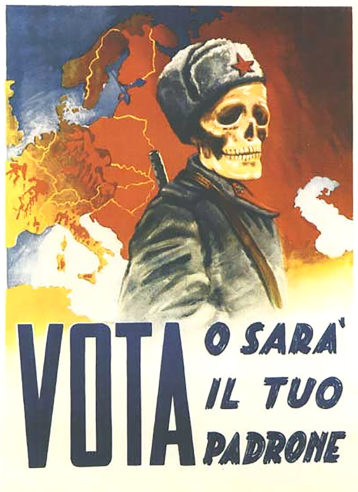

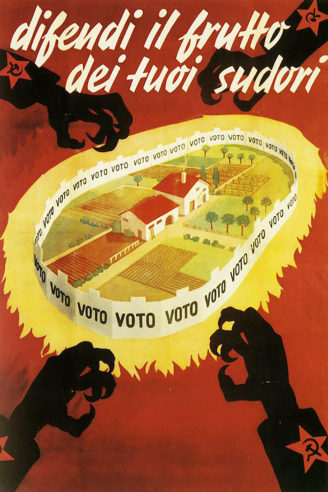

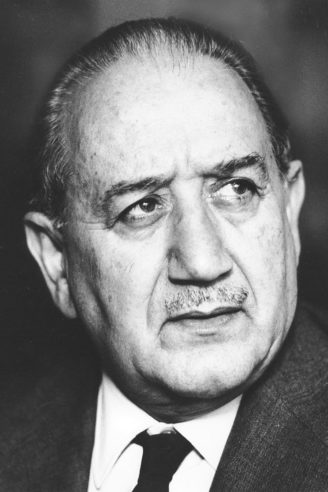

CIA’s first test in psychological warfare came in 1948, when it looked like the Communists, who dominated the left-wing Popular Democratic Front led by Palmiro Togliatti, might win the election in Italy. The agency spent between $10 and $20 million to prop up Alcide De Gasperi’s Christian Democrats, who ended up winning by a 17-point margin.

CIA distributed anticommunist leaflets, published forged letters to discredit Italian Communist Party leaders, convinced Italian Americans to mail real letters to their relatives urging them not to vote for the Communists and gave money directly to the center parties.

Togliatti later spoke of “brutal foreign intervention,” which was an exaggeration. But CIA wasn’t innocent, and Italy became a template for interventions elsewhere.

American spies would back friendly labor unions and center-left parties as alternatives to communism. Former communists and moderate leftists, including artists, writers and other intellectuals, were recruited to disavow communism and promote a moderate form of socialism.

War of ideas

The challenge, writes Frances Stonor Saunders in Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War (1999), was turning the benign image of Russia that had been cultivated during the Second World War, when capitalists and communists were allies, into a red menace.

Culture was an area in which the oppressive nature of Soviet communism could be contrasted with the freedom and vitality of the West. In Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe, every aspect of culture, from architecture to fiction to music, was censored and controlled by the state. In the West, there were few limits on the freedom of expression.

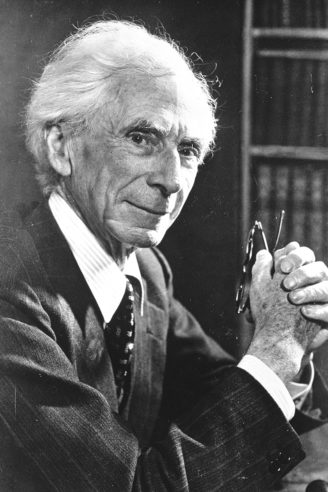

The Congress for Cultural Freedom, founded in 1950, played a major role in challenging claims of intellectual “neutrality” in the East-West standoff. Among its founding members were French philosopher Raymond Aron; John Dewey, the leading American theorist on democracy; British philosopher Bertrand Russell; American historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr.; Italian antifascist author and politician Ignazio Silone; and American playwright Tennessee Williams.

The Congress, which first met in Berlin, brought together artists and thinkers from both sides of the Atlantic who opposed Soviet tyranny and supported a united Europe. It published magazines, held exhibitions, and organized awards and conferences.

In 1952, the Congress held a Masterpieces of the Twentieth Century festival in Paris, which Giles Scott-Smith writes in “The Congress for Cultural Freedom and ‘Masterpieces of the 20th Century’: Origins and Consolidation 1947-1952,” published in Intelligence and National Security 15 (2000), boasted “not only achievements by Western artistes but also work by East Europeans which was forbidden by Soviet cultural diktat.”

The festival attracted major interest, funding and participation, but poor reviews in the French press, which saw the event as a harbinger of the “Coca-Colonization” of their culture.

They would have been shocked to discover just how Americanized the festival really was; the entire Congress for Cultural Freedom was paid for by the CIA.