Old war movies are frequently smeared as jingoistic and morally simplistic. There is also the reckoning with François Truffaut, who argued no movie can ever truly be antiwar.

But the history enthusiast in me always finds something to enjoy in these movies, where heroic Americans, Britons and Allies (almost always from the Anglosphere) in awe-inspiring tanks and sleek propeller planes fight the good fight against cruel Nazis and Imperial Japanese.

Nor are these films as uncritical as they are sometimes made out to be. The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), The Bridge at Remagen (1969) and even bits of The Guns of Navarone (1961) show the sheer cruel madness of war.

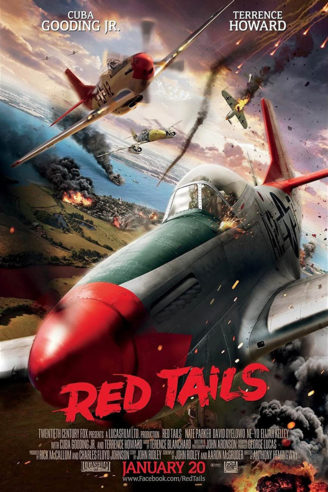

It is in this context that we must consider Red Tails, the 2012 movie about the Tuskegee Airmen, the African American fighter pilots who battled both American racism and German military might in Italy.

It does much the same things as The Great Escape (1963) or The Guns of Navarone, where Americans are heroes and Germans are villains, with the twist of race relations woven into the plot as any movie about the Tuskegee Airmen must. In this, it is far more nuanced morality-wise than the stereotypical old war movie, moving it more into the territory of The Bridge of Remagen and showing that American racism deeply affected the war effort, both in Europe and at home.

It is worth noting that this film is ultimately the brainchild of George Lucas; his drawing for inspiration from old World War II movies for Star Wars and its space combat is well-documented. The famed Death Star trench run was taken from The Dam Busters (1955). It is fitting, then, that Aaron McGruder, one of the film’s writers (and famed for Boondocks), said that:

Some people are going to like this tonal choice and some people are going to say, “Oh it should’ve been heavier and it should’ve been more dramatic.” But there’s a version of this that doesn’t have to be Saving Private Ryan. We can be Star Wars, as crazy as it is.

That is, indeed, what this film is: a more fun, simple adventure, rather than the morally complicated war movies have been à la mode in the past few decades. At some point, we can acknowledge that the Allies, for all their myriad flaws, were the better side in the war than those who committed heinous crimes at Auschwitz and Pingfang. In the twenty-first century, the great mid-century war films may be an acquired taste, requiring some historical context to enjoy, and this film is one of those displaced out of time and with a black cast.

As a war film, it succeeds dramatically, with spellbinding action in the skies over Italy. There are ample dogfights, as one would expect from a movie about fighter pilots, and one particularly fantastic scene in which they level a German airstrip. Another scene, not quite historically accurate but deeply impressive, is when one of the Red Tails destroys an Italian ship with nothing more than strafing.

The soldiers here seem like soldiers, fully fleshed-out ones to boot. You run a gamut of personalities, from the hotshot Casanova to the more serious reserved officers, but they are united in their opposition to both domestic racism and foreign guns. One has a whirlwind romance with an Italian woman he spotted from his plane on a tower, and it is as touching as it is brief.

Red Tails is traditional in an age where tradition is increasingly seen as backward and irrelevant. In this case, the tradition’s strength is shown in dazzling new form, and the film is better for it.