As Barbarossa began, Soviet troops at the front were often asleep.

When the Germans struck, their stocks of ammunition and fuel were low without any preparation for a fight and the stockpiles available were often either destroyed or captured within the first days of the conflict. The Red Air Force planes were arranged in neat rows for the Luftwaffe to destroy, leading to over a thousand planes lost on the ground. For the first week of the war, the Soviets lacked any form of centralized high command; a situation further exacerbated by lines of communication having been disrupted by the invasion and often non-existent with a lack of access to adequate codes meaning that the railway telephone was often the only link between the troops on the ground and the leaders of the Soviet state.

It was in this environment that desperate counterattacks were ordered up and down the front, all of which inevitably failed. Soviet formations instructed to attack were often unable to discern which direction they were supposed to be attacking toward, or, in the words Red Army Captain Anotoli Kruzhin,

Not [able] to find where the enemy was positioned, but Soviet units, — their own army!

The Red Army was like a blindfolded boxer with one arm tied his back, flailing around and desperately throwing punches at an experienced opponent, unable to land a significant blow or even to see where he should be aiming.

These failures made a catastrophe in the first weeks of the German-Soviet war an inevitability for the Red Army, but to what extent could their performance have been improved had they been allowed to prepare?

The answer, ironically, lies in the reason for their lack of preparedness.

April-May 1941: Denial and desperation

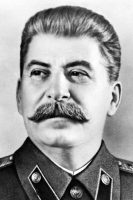

The reason for Joseph Stalin’s belief that Germany would not attack in 1941 was based far too much on a crucial misunderstanding of German intentions that complemented his own wish fulfillment. It’s unlikely that Stalin ever had any doubts that Hitler wanted to destroy the Soviet Union, but he chose to ignore the warning signs that by the late spring of 1941 should have been unavoidable that an invasion was coming that year.

The reason for this, primarily, was that the Soviet Union was not ready for a war in 1941.

The Red Army was in the midst of a major expansion and reorganization, having quadrupled in size since 1939, and trying to learn the lessons of the Winter War with Finland that had revealed glaring problems with its organization and strategy. A new line of fortifications was being built along the new German-Soviet frontier but was nowhere near complete, nor was the Red Army’s replacement of its older light tanks such as the T-26 with newer, heavier models like the T-34 and KV-1 anywhere near completion.

Stalin had hoped that the Red Army would have enough time to wrinkle out these difficulties, relying on a long war between Anglo-France and Germany, but with the fall of France in 1940 and subsequent isolation of the United Kingdom he was desperate to buy more time in the knowledge that Germany was now free to turn east. As the evidence of German preparations for the invasion of the Soviet Union piled up in the spring of 1941 Stalin embraced a strategy more commonly associated with the British: appeasement.

Vast shipments of grain, oil and other resources were shipped to the Nazi empire in the May and early June of 1941 (some, bizarrely, without request) in the hopes that Hitler could be made to see that peaceful trade with the Soviet Union was far more preferable to war. Hoping to put German minds further at ease, overt Red Army preparations for defense were often ordered to be more discreet or even halted so as to make it clear that the Soviet Union was not judging war to be inevitable. Even as German officers in occupied Poland talked openly of the imminent invasion, Stalin was still sure that he could secure a reprieve that would allow a year of breathing space for the Red Army. In doing so, he merely left the Soviet Union in a far weaker state than it might have been.

Had Stalin been more open to the evident warnings of what was about to happen, Soviet intelligence would have been able to pull off a victory that was prevented in our time. Richard Sorge, the Soviet master spy working within the German embassy in Tokyo had happened upon the plans, intentions and even the start date of the Barbarossa plan. This information was marked as “doubtful” when it reached the Kremlin in April 1941, but what if it had been marked as “trustworthy” instead?

June 1941: “Don’t die without leaving a dead German behind you!”

Had the Soviets spent the months prior to Barbarossa preparing for the German invasion, they could have addressed many of the problems that enabled the disaster on the frontiers in our time.

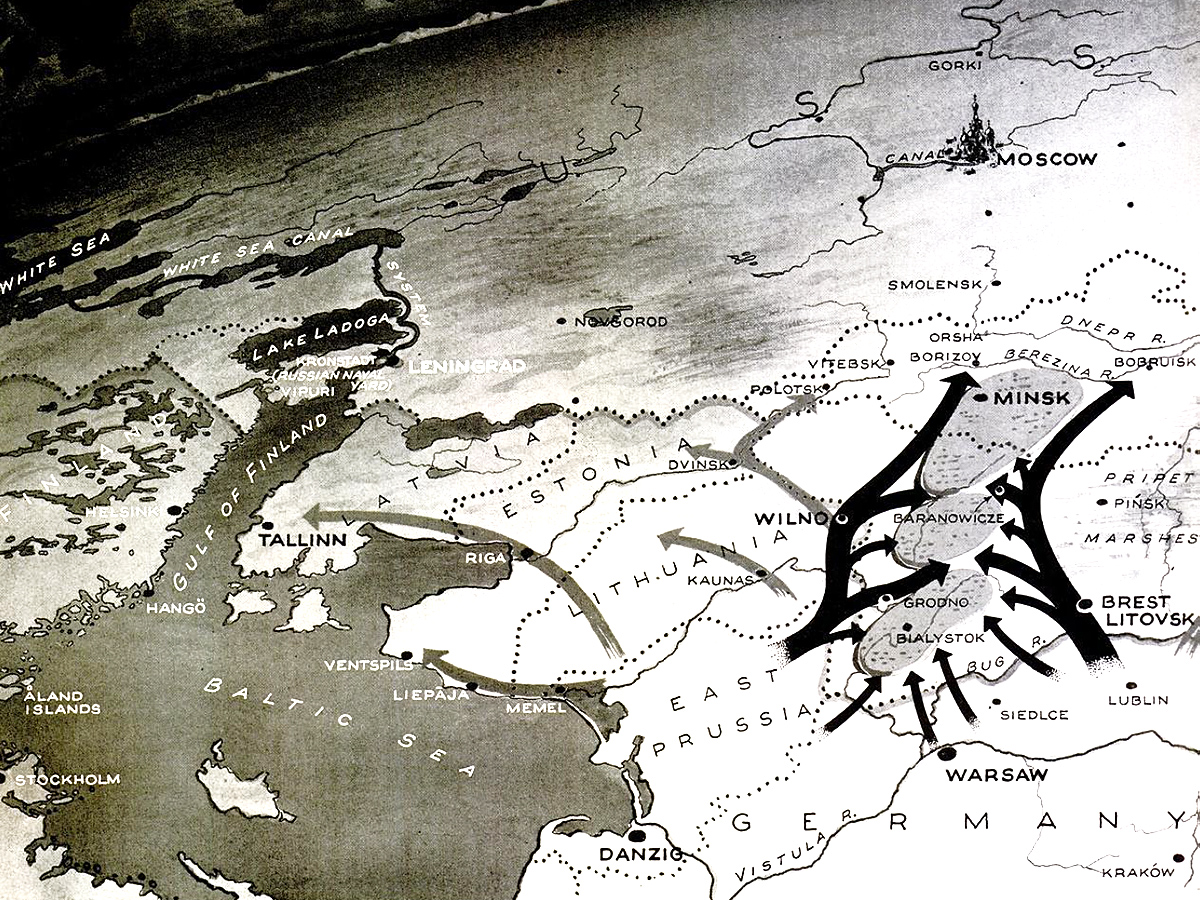

Construction on the not-even-half-built defensive line on the German-Soviet border would have been abandoned in favor of the already complete Stalin Line that had been based on the old Soviet-Polish border. This line would have allowed the Soviets to be entrenched in depth when the invasion came. Without the best of their armies trapped in the initial German artillery barrage, they could instead wait for the Germans to come to them where the Red Army could apply generous amounts of artillery fire on the advancing Germans from their own strategic “choke points”. Knowing the precise date of the invasion, preparations could have been made to ensure the Germans would have received a warm welcome in this regard.

If the Red Army had undergone mobilization a few weeks in advance prior to the beginning of Barbarossa, it would have nearly doubled in size, from a force of 5.5 million to 9.6 million by the time the mobilization would have ended. This second strategic echelon would have ensured that rather than being outnumbered in the opening stages of the German-Soviet war, the Red Army would have enjoyed a large advantage in manpower. Further echelons would have brought that strength closer to 14 million, comprising all Soviet reservists in the broadest definition, although this would have taken several more months, according to historian David Stahel.

To face this entrenched and rapidly expanding enemy, the Germans would have had to cross rivers with bridges blown and across countryside riddled with mines pre-laid while in the skies they could no longer rely on the Luftwaffe having things entirely its own way. Could the Wehrmacht have possibly overcome this enemy that was intact and ready to fight?

More than likely.

In spite of its preparation, the Red Army would still have to contend with equipment that was often obsolete and broken down or simply lacking as in the case of radios. The vast losses in tanks due to mechanical failure would likely still have happened, even if greater diligence prior to the invasion might have alleviated the situation somewhat. The Red Air Force would have been massacred, not on the ground but in the skies. Ironically the situation for the Red Air Force may have been worse had they flown to meet the Luftwaffe. At least on the ground, the pilots avoided the carnage to fight another day in better aircraft. The Red Army’s shortages of ammunition and fuel would still have hit hard. Greater awareness of the German threat wouldn’t have been enough to solve the limitations of the Five Year Plan’s inadequate quotas even with a greater rush to prioritize arms manufacture. The Red Army would have remained inexperienced for the most part and its leadership would often have remained inept.

In airpower, doctrine, experience and leadership, the Germans would have had the clear advantage and it’s difficult to see the battle of the Stalin Line ending in anything other than a protracted and bloody German victory. The mantra of accepting death but resolving to take as many of the enemy with them was one that had been forced on the Red Army by circumstances that predated Stalin’s unwillingness to prepare for a German invasion, but without this hindrance the Red Army could have ensured that it was the last real German victory of the war.

The opening battles of Barbarossa would have been measured in months rather than days or weeks and German losses in men and equipment, unexpectedly high in our time, would have spelled the end of the invasion before it had truly begun.

With the destruction of the Stalin Line, the Soviets would have suffered severe losses themselves, but it’s unlikely these would have been as heavy as in our time and a drawn-out battle would have allowed a far better organized retreat to the Dnieper River. Running through Western Belarus and Ukraine, this is where the German advance would have ground to a halt. The battered German forces would have had to cross a giant natural obstacle defended by fresh armies and the remnants of those who had escaped the frontier battles. The Wehrmacht, victorious but worn-out, would be forced to pause to lick their wounds. Unable to threaten Smolensk or Kiev, let alone Leningrad or Moscow, until their vast losses in men and materiel could be replaced.

It is likely they wouldn’t have to wait long until they realized that the Red Army, intact and growing stronger, would be the ones to strike the next blow.

Conclusion: The decisive battle that never was

The Red Army troops stationed on the German-Soviet border were unforgivably forced to fight with one hand tied behind their back, not only due to the failures of the Soviet leadership to heed the warning signs of an imminent German invasion, but there is no doubt that it severely curtailed their ability to resist when they were already facing terrible odds.

Although it’s unlikely that a better prepared Red Army could have driven the Germans back in the early weeks of Barbarossa, it is possible that their sacrifice could have forced the Germans to halt farther west than they did historically, sparing millions from Nazi occupation and ensuring that the Soviet Union would have been on a far stronger footing to repel the Germans and march on Berlin much earlier than in our time. Barbarossa would have still have been traumatic for the Red Army; the scale and intensity of the Axis invasion ensured that. But those who died in those first weeks would have ensured that the German hopes of conquest died with them had they been allowed to fight to the best of their ability.

But what if the Soviets had taken a more “proactive” approach to the signs of an inevitable German attack? After all, it’s often said that the best defense is…

Find out next time!

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.

2 Comments

Add YoursInteresting. The “German-Soviet Border” ran down the middle of Poland, of course. On the 81st anniversary of Britain’s and France’s declaration of war on Germany for invading their supposed ally Poland, we may once again reasonably wonder why they did not declare war on the Soviet Union when the Soviets also invaded Poland on September 17th.

True – and something that tends to be left out of the Russian history books…