What if Japan had joined Barbarossa in the summer of 1941?

It’s a question that’s interested many and even puzzled a few ever since before the end of the Second World War.

“It should be clearly made known to Russia that she owes her victory over Germany to Japan, since we remained neutral,” were the words of Kantarō Suzuki, the Japanese prime minister, on May 14, 1945.

This was a belief that arguably stemmed from desperation on the part of the Japanese. It was expressed following the capitulation of what was left of the Third Reich the previous week, where Japanese hopes now lay in the Soviet Union’s willingness to mediate a peace between Japan and her numerous enemies. In the end these attempts came to nothing and as the Soviets joined the war against Japan in August, perhaps some within the Japanese leadership wondered if they’d made the right choice to spare the Soviets in the summer of 1941…

North versus south: July 1941

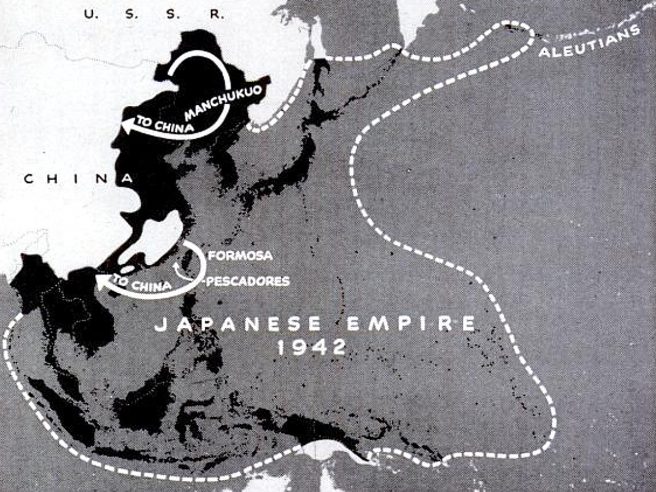

In retrospect, the reasons as to why the Japanese chose to invade Southeast Asia near the end of 1941 rather than the Soviet Far East seem fairly self-evident: Japan was already bogged down in an four-year long war against what was left of the Republic of China and the Chinese Communists, and faced increasing economic constraints from the United States, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

Nonetheless the Japanese Kwantung Army, responsible for the occupation of Manchuria (modern-day Northeast China, then the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo) reacted to Operation Barbarossa with their own plans for an invasion of the Soviet Union.

They had a key ally in the Japanese foreign minister, Yōsuke Matsuoka, who in April had signed a Nonaggression Pact between Japan and the Soviets but now argued fervently for Japan’s involvement in the “crusade against Bolshevism”.

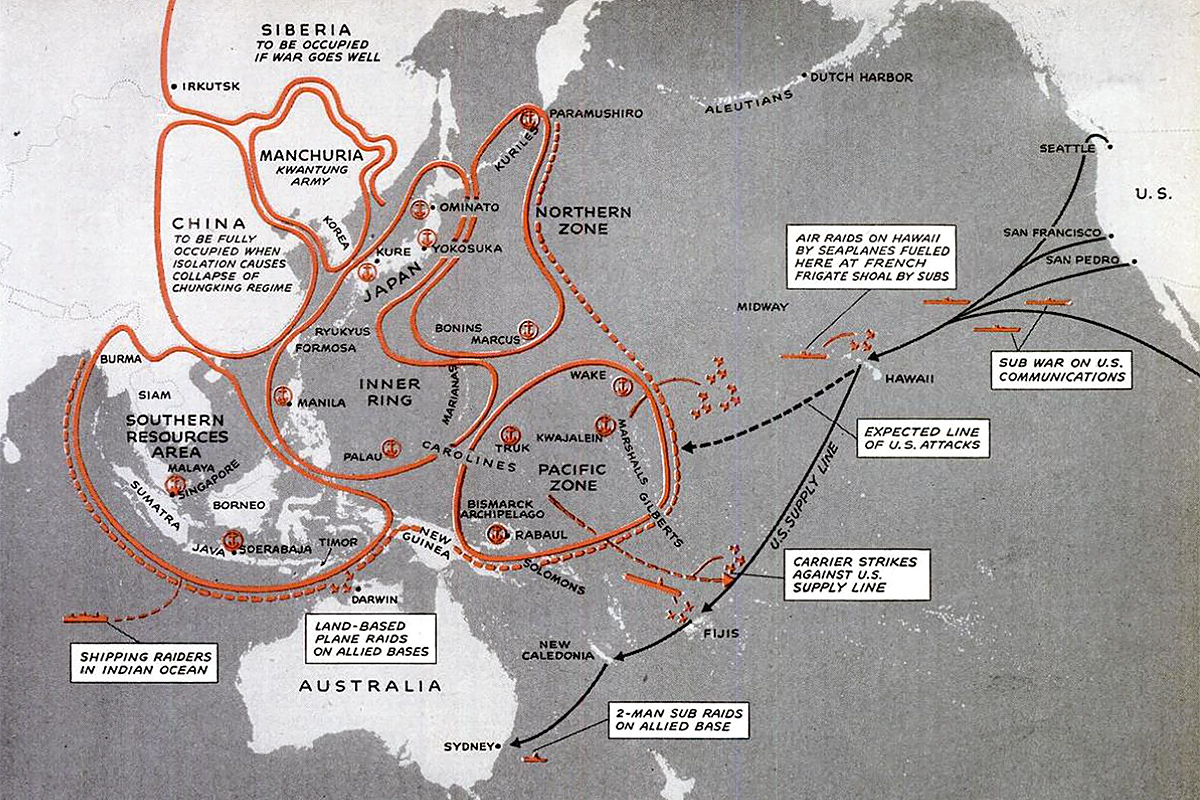

The Japanese plan for the invasion of the Soviet Union (innocuously titled “Special Maneuvers”) would have been dwarfed by the Axis offensive to the west, but it would nonetheless have been the biggest undertaking in Japan’s long military history.

The plan called for seven Japanese armies to attack the Soviets along a broad front stretching from the Sea of Japan to Outer Mongola with a multi-pronged offensive that would see the Japanese capturing much of the Far Eastern Soviet Union south of the Amur River between the cities of Chita and Komsomolsk-on-Amur with potential expansion being planned even further north and west being planned subsequently.

A separate operation would also see the Japanese capturing the Soviet-controlled half of the island of Sakhalin. This plan was ambitious, but it was also somewhat underwhelming compared to previous Japanese plans for conquest of the Eastern Soviet Union, a factor that played into the skepticism of the plan to strike north.

The potential gains would have provided little for Japan’s economic woes. The Soviet Far East had many resources, but the ability to exploit and transport them to Japan was lacking, and there was little oil or rubber to be found there at that point in time.

The Kwantung Army’s poor performance against the Soviets in frequent border clashes in the late 30s, culminating in their humiliating defeat in the Battle of Khalkhin Gol in 1939, cast doubt on the ability of the plan to succeed at any rate.

Striking south, on the other hand, offered the prize of a vast empire of readily exploitable resources that were defended by poorly prepared and often second-rate colonial troops left there by nations focused on the war in Europe. The Japanese occupation of French Indochina in mid-July was met with an even tighter western embargo, further underlining the empire’s desperate need for access to large amounts of resources as quickly as possible.

While communism was universally despised among the Japanese establishment, and there might even have been an admission that the Soviet Union posed the greater long-term threat to Japan, there was a clear consensus that heading south was the only real option for those who didn’t wish to back down to Allied demands to withdraw from China.

In essence, the northern option was considered too nonsensical by the guys who considered declaring war on the United States (a country that had an industrial base ten times larger than their own) to be a reasonable foreign policy objective.

With that indictment in mind, let’s see how it might have panned out.

The Japanese Invasion of the Soviet Union, September 1941

The Kwantung Army would have had the advantage in numbers in such a scenario, with around 700,000 men going up against the Red Army’s 550,000 men of the Far Eastern Front and Transbaikal Military District, while the Red Banner Pacific Fleet would have been little match for the Imperial Japanese Navy, ensuring Japanese control of the sea.

The overall picture was much more dreary.

The Red Army would have enjoyed a large advantage in aircraft, artillery and in tanks. Furthermore, the Red Army would likely have known that the Japanese were coming, having followed the Kwantung Army’s “Special Maneuvers” with alarm historically. Had such a large Japanese force began to assemble on the border, the Soviets would likely have begun to prepare.

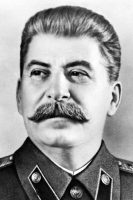

It could be argued that this was also the case for the German build-up prior to Barbarossa only for the Soviets to be caught by surprise regardless, but it appears that Joseph Stalin had learned his lesson. Historian John Erickson notes that after Barbarossa, the Soviet forces in the Far East were ordered to be on alert for any signs of an impending Japanese attack.

By September 1941, provided the forces could be assembled on time, the Japanese would have launched their invasion against an numerically inferior but far better equipped foe, and while Soviet Sakhalin would likely have fallen rather quickly the offensive on the mainland would almost immediately have been bogged down amidst Soviet armor and airpower.

It is unlikely the Soviets would have been able to repulse the Japanese entirely, with the Japanese ability to cut-off the Trans-Siberian Railroad supply would have been tenuous. But the Japanese would have faced their own constraints advancing with such a large force into rough terrain with few roads. After several days of intense battle between the two armies, the dust would have settled and a stalemate would have arisen, the Japanese unable to advance yet the Soviets unable to dislodge them from their meager gains. The Far Eastern Front would have quickly descended into a slow war of attrition, and the Japanese could not afford to run out the clock.

Having invaded the Soviet Union, the Japanese would have found an enemy in the United Kingdom as well, with Winston Churchill likely declaring war on Japan or at the very least doing everything short of war to harm their war effort, with the Dutch and the United States following suit.

In our time, Japan was able to temporarily stave off their resource scarcity with their conquests, but bogged down across the Soviet border they would have captured little to offset their losses. In his article “Oil Logistics in the Pacific War,” Lieutenant Colonel Patrick H. Donovan points out that by September 1941,

Japanese reserves had dropped to 50 million barrels, and their navy alone was burning 2,900 barrels of oil every hour.

The Soviets would not have had to drive the Japanese out of the Far East. The Allied embargo would have done that for them before the end of 1942.

The impact the Japanese invasion would have had on their German allies would undoubtedly have been a beneficial one. The Soviets had sufficient forces to hold back the Japanese invasion in the Far East, but these were forces that from September onward were often transferred to European Russia in our time. Most famously, several Soviet divisions which were either based or subsequently raised in the Far East would eventually take part in the defense of Moscow and the subsequent Soviet counteroffensive, but their impact is often overstated. Of the roughly seventy divisions of all types that took part in the Soviet counteroffensive, only eleven originated from the Far East. For comparison, the Soviets used twelve divisions to launch a counteroffensive in Crimea historically. In spite of the Japanese sacrifice, the Germans would still likely have been flung back.

Conclusion: A gamble without stakes

The fact that a Japanese invasion of the Soviet Union can only really be seen as a potential benefit from the German’s perspective is rather telling in regard to the overall flaw in this what-if scenario. The Japanese had their own aims, irrational as they were, that would have prevented them from ever seeing an invasion of the Soviet Union as a priority, with their past experience in fighting the Red Army and the urgency of their resource situation making this an even less likely scenario. The Japanese strike at Pearl Harbor, and their subsequent invasion of Southeast Asia, may have been a desperate gamble, but it was at least one which potential rewards. Invading the Soviet Union would only ever have been a dead end.

But could the Germans have found more willing partners elsewhere?

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.