It is debatable when the history of the Japanese Empire began. One can go back to the Meiji Restoration of 1868, but wasn’t the 1894-95 Sino-Japanese War, fought over influence in Korea, really the starting point of Japanese imperialism?

Or the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War? Fought for influence in Korea as well as Manchuria.

Or 1910, when Japan annexed Korea?

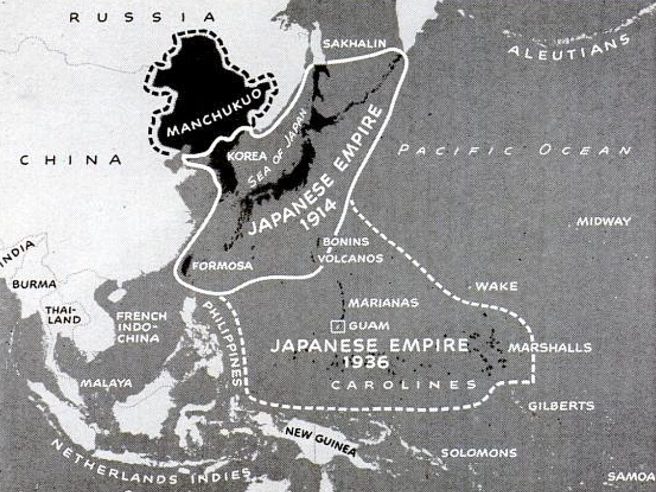

A watershed moment came in 1931, when Japan occupied Manchuria. There was no doubt at that point the island nation had become a colonial and an expansionist power.

Puppet state

In September 1931, units of the Japanese Kwantung Army, stationed in Manchuria since the Russo-Japanese War, used a staged Chinese attack as a pretext to lash out. Within days, they had seized an area 1.5 times the size of Texas.

Civilian leaders in Tokyo were appalled their soldiers had acted without permission, but what could do they? There was no turning back from empire now.

Japan made Manchuria a puppet state, called Manchukuo, and put the ousted Qing emperor of China, Puyi, at its head. (These events are portrayed in the 1987 film The Last Emperor.)

The ancestral homeland of the Manchurian Qing Dynasty, which had ruled China for nearly 300 years, the majority of the occupied territory’s population was nevertheless Han Chinese. Some ten million of them were forced to toil in heavy industries, which produced the steel and other raw materials needed to fuel the Japanese war machine.

Island empire

Japan already presided over various islands in the Pacific as League of Nations mandates: the Carolines, Palau, the Marshall Islands, what are now the Northern Mariana Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia, all of which Japan had inherited from Germany after World War I.

Although Japan withdrew from the league in 1933, it kept the islands. They conveniently surrounded American-held Guam. Japan built airfields, fortifications and ports throughout its Pacific empire in the 1930s in order to defend the Japanese home islands against a future invasion and serve as staging grounds for Japan’s offensive in the Second World War.

Second war with China

After the occupation of Manchuria, China and Japan were never at peace. More battles and “incidents” took place, the result of which was always to push Japanese control further south.

By the middle of 1937, the Japanese army had advanced to the outskirts of Beijing (Peiping) and Tianjin (Tientsin), the two major Chinese cities in the north. Fighting escalated on the night of July 7, when Chinese and Japanese troops exchanged fire near the Marco Polo Bridge southwest of central Beijing. This triggered the Second Sino-Japanese War.

The Japanese quickly conquered Beijing and Tianjin. In August, they attacked Shanghai. A bloody siege, which historians now call the “Stalingrad on the Yangtze”, began. It took the Japanese three months to break the Chinese resistance.

By the end of the year, they had also seized Nanjing, then the capital of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang government. Up to 300,000 Chinese civilians and troops were killed in what became known as the Nanjing Massacre.

The Nationalists evacuated to Chongqing, deep inside mainland China, where they holed up until the end of the war.

Communist guerrillas, led by Mao Zedong out of Shaanxi, were similarly undefeated. Although the Japanese would use evermore brutal tactics, including massive air raids on populated areas, the Chinese never gave up the fight.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The next step in the Japanese expansion would ultimately prove its undoing.

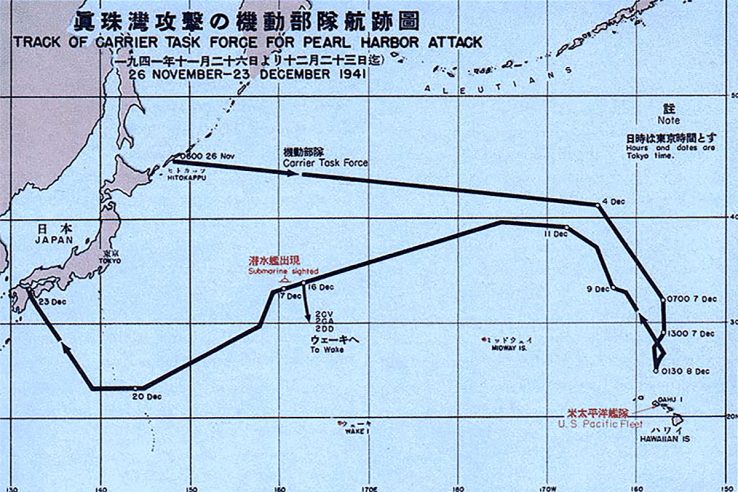

Japan hoped that by disabling the American fleet at Pearl Harbor, it could keep the United States out of the war and defeat the British and Dutch in Southeast Asia.

The surprise attack had the opposite effect: the United States not only declared war on Japan; Japan’s European allies declared war on the United States, making the war a world war that would crush the Axis powers in the end.

No plan to invade the United States

Life revealed as early as December 1946 that the Japanese never had any intention to invade the continental United States. Basing itself on “captured documents” and interviews American officers had conducted with their Japanese counterparts, the magazine reported that the empire’s goal was always a negotiated peace.

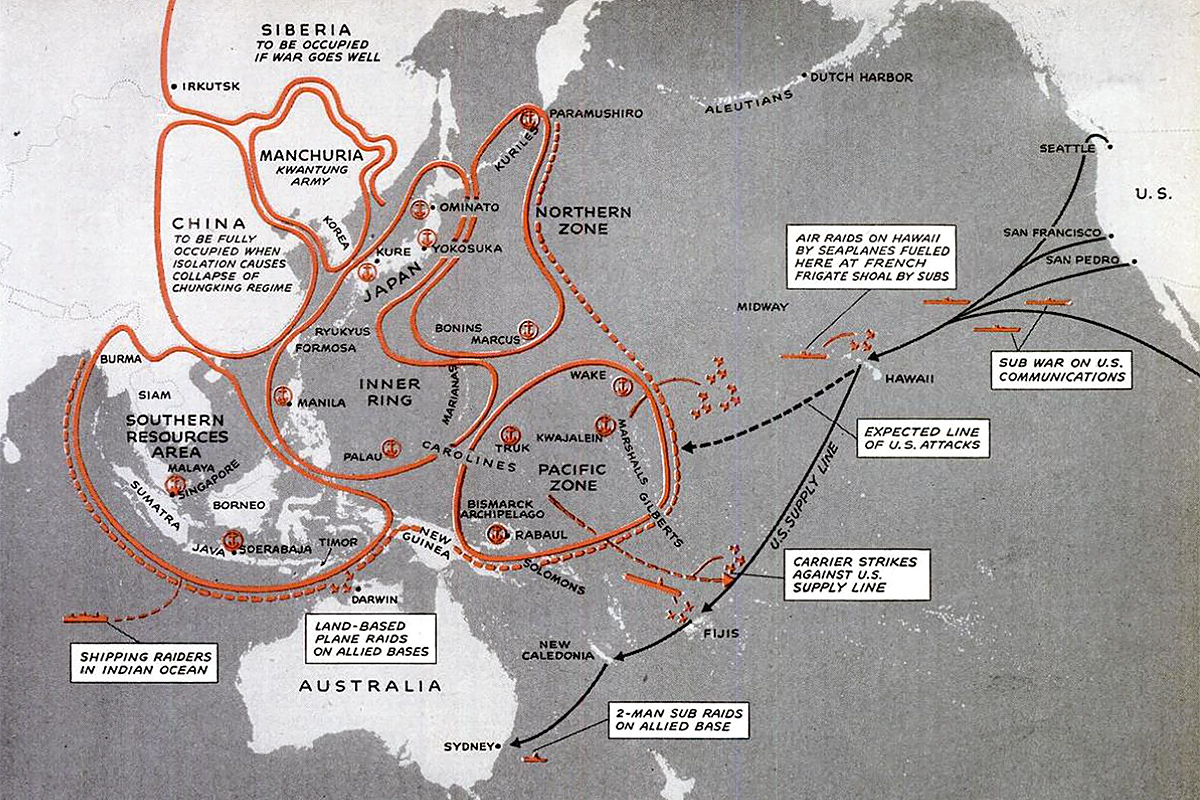

The strike on Pearl Harbor was only meant to immobilize the American fleet so the Japanese could take the Philippines, Guam, Singapore, the East Indies and Wake Island.

Then the Japanese thought they would have time, behind their outer defenses, to exploit their new “southern resources zone” for raw materials which they needed to complete their hopelessly deadlocked war in China.

Height of expansion

When the war went better than expected, Japan’s leaders, shocked by the 1942 Doolittle Raid on Tokyo, miscalculated: they extended their defensive perimeter to include Kiska, Midway, New Caledonia and all of New Guinea.

It was a rash decision that cost them many carriers and planes, leaving Japan vulnerable once the United States had fully mobilized.

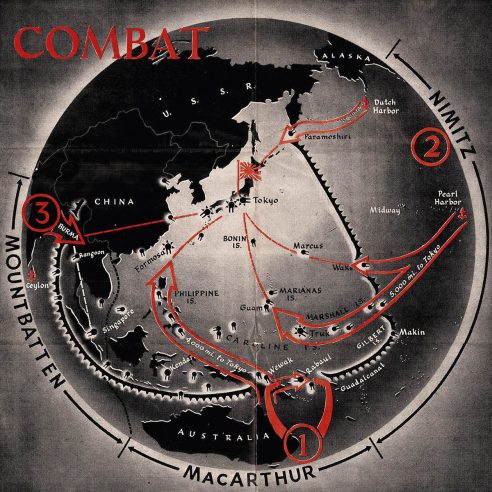

War on three fronts

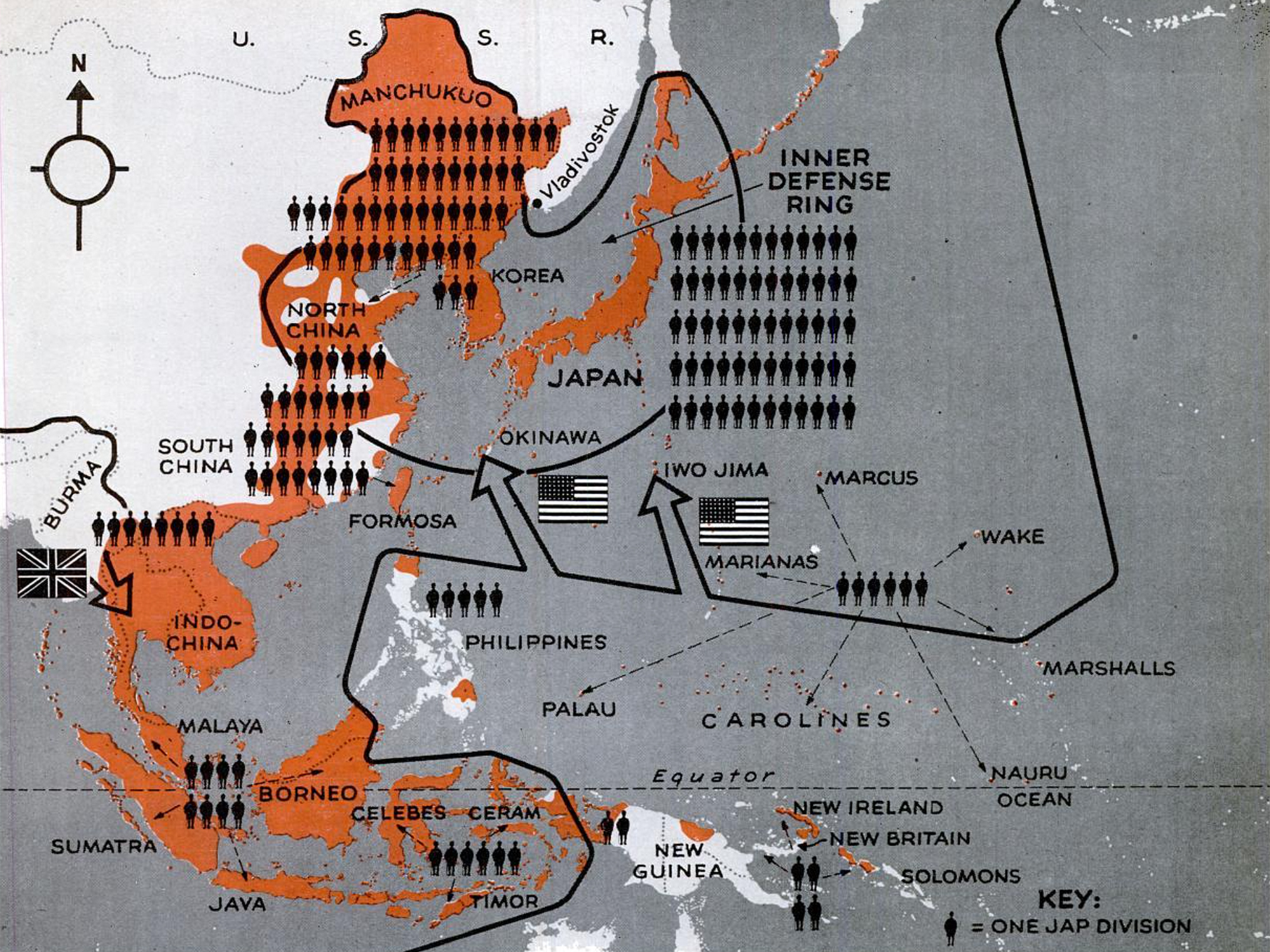

By late 1943, the Allies had seized the initiative and Time magazine was speculating about where they would go on the offensive.

From India, it suggested, Lord Louis Mountbatten could direct a campaign against Burma. From Honolulu, Admiral Chester Nimitz could attack with carrier forces and amphibious troops across the Pacific. Between them, General Douglas MacArthur would advance along New Guinea to a position which could threaten the East Indies.

This more or less supplementary role was not MacArthur’s idea, Time knew. His ambition was to drive for the Philippines, where he had served as chief military advisor before the war, knocking out flanking Japanese island bases on the way.

Leapfrogging enemies

The liberation of the Philippines would have to wait. Allied victories at Midway and in Guadalcanal led to a leapfrogging, or island-hopping, strategy: heavily-fortified Japanese positions were sidestepped in favor of lightly-defended islands that could nevertheless support the advance on the Japanese home islands.

The Allies deliberately avoided a decisive naval battle, waging submarine warfare instead and depriving the Japanese of critical oil supplies.

A doomed 1944 invasion of India further weakened the empire, allowing Mountbatten to take back Burma.

In the Pacific, the Americans seized Saipan in the Northern Marianas and Guam, putting their B-29 bombers within reach of the Japanese homeland. The Imperial Japanese Navy lost most of its remaining capital ships in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, which paved the way for MacArthur to return to the Philippines in October 1944.

The last major engagements of the war were also some of the bloodiest: the battles for Iwo Jima and Okinawa and the Australian-led liberation of Borneo.

At Okinawa, 94 percent of the 117,000 Japanese troops defending the island fought to the death. Kamikaze attacks on Allied ships had become commonplace. Almost half of the built-up areas of Japan’s major cities were destroyed in B-29 firebombing raids. On March 9-10 alone, some 100,000 Japanese civilians were killed in the Bombing of Tokyo.

Atomic bombings

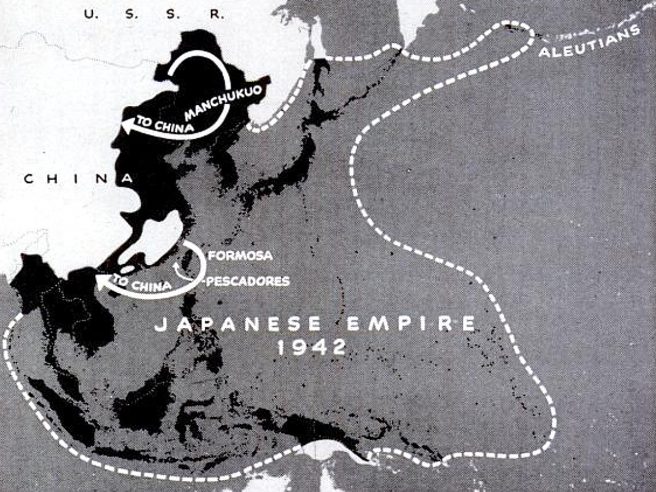

By the summer of 1945, Japan still controlled a vast empire in Asia, stretching from Manchuria in the north to Java in the south. Allied troops were within reach of the Japanese home islands, but it was estimated that an invasion — codenamed Operation Downfall — would cost hundreds of thousands, possibly millions, of lives and prolong the war by two years.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the simultaneous invasion of Manchuria by more than one million Soviet troops, made an invasion unnecessary. Japan announced its surrender six days later.

Between 90,000 and 146,000 people were killed in the bombing of Hiroshima. Between 39,000 and 80,000 were killed in Nagasaki. Many more perished in the aftermath from burns, radiation poisoning and other illnesses.

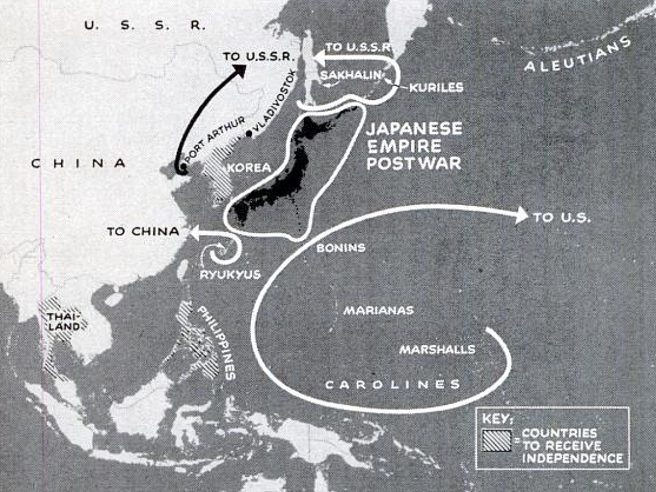

Plans for dismemberment

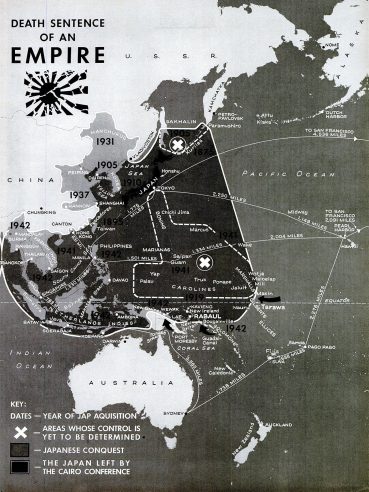

American president Franklin Roosevelt, British prime minister Winston Churchill and Chinese generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek had agreed in Cairo in 1943 that Japan would be forced to surrender all the territories it had gained during the war.

But that left same questions. What about the islands Japan had ruled as League of Nations mandates? What about Sakhalin and the South Kuril Islands, which Japan and Russia had contested for decades? And what about the former European colonies in Asia? The American preference was for independence, but Roosevelt had avoided broaching the topic for fear of alienating the British, Dutch and French.

Lasting consequences

Most of the liberated territories were returned to the powers that had controlled them before the war: Manchuria and Taiwan to China, Indochina to France, the Dutch East Indies to the Netherlands, Burma, Malaya and Singapore to the United Kingdom and Guam and the Philippines to the United States.

The United States also took control of the Ryukyu Islands, including Okinawa, as well as the remaining islands of Micronesia until 1972 and 1986, respectively. The latter were organized into the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of Palau and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands.

Two of the territorial decisions taken after World War II would have long-lasting consequences:

- It emerged that, at Yalta, Roosevelt had secretly traded Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands to the Soviets in return for their entry in the Pacific War. Japan still refuses to recognize Russia’s claims.

- Korea was divided into American and Soviet zones of occupation. When the North attempted to reunify the peninsula on its terms, the United States and twenty other nations came to the South’s support in 1950. Neither side prevailed in the Korean War. The peninsula remains divided to this day.

1 Comment

Add YoursInteresting, though Japan did declare war on the US before the US declared war on Japan.