Cities lost to time and half-remembered civilizations, discovered deep in the mountains of the Himalayas, the Amazonian rainforest or at the bottom of the sea, are a familiar trope in steam- and dieselpunk fiction.

Drawing on the expeditions of Percy H. Fawcett and Heinrich Schliemann, the writings of James Churchward and Theodore Illion and the esotericism of Helena Blavatsky, W. Scott-Elliot and Rudolph Steiner, both genres exploit the half-real and fully imagined tales of ancient races that supposedly roamed the Earth millennia ago.

Mu

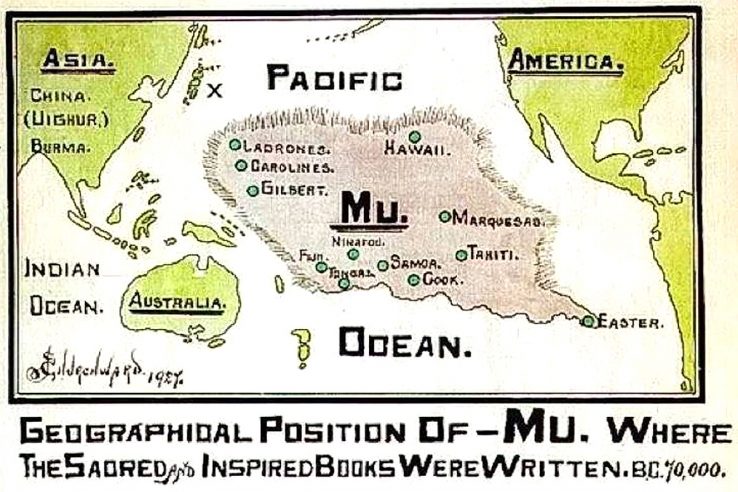

James Churchward, a British-born Sri Lankan tea planter, claimed in his 1926 book The Lost Continent of Mu, Motherland of Man to have learned of an ancient Pacific civilization from an Indian priest, who taught him the language of the Naacal: a people who, according to French explorer Augustus Le Plongeon, lived in the Pacific tens of thousands of years ago.

Translating ancient tablet inscriptions, Churchward uncovered the history of Mu, the homeland of the Naacal people: a vast continent in the Pacific Ocean, stretching from the Marianas in the east to Easter Island in the west and Hawaii in the north to the Cook Islands in the south.

When volcanic eruptions sunk the once-flourishing civilization, the people of Mu spread out across the world. Ancient Egypt, Greece, Central America and India all trace their origins to Mu, according to Churchward.

Like so many lost worlds, Mu was, in Churchward’s telling, a land of plenty. Tropical weather, beautiful plains and valleys, slow-running streams and rivers, “shallow lakes bejewelled with sacred lotus flowers in emerald green settings” and “tiny hummingbirds, glistening like living jewels in the rays of the sun.”

Another trope we’ll find in later ancient-civilization myths: the white man descending from Mu’s priestly, patrician class. According to Churchward, Mu’s darker-skinned inhabitants knew their place in the racial hierarchy. I’m afraid this won’t be the last time white men glean the origins of their “master race” from ancient Asiatic wisdom.

Mu appears in several Japanese cartoons and video games, Marvel Comics and H.P. Lovecraft’s story short, “Out of the Aeons” (1935).

Lemuria

Another sunken continent, this one in the Indian Ocean. Nineteenth-century zoologists postulated Lemuria’s existence to account for fossils found in India and Madagascar but not in Africa and the Middle East. Their theory has been superseded by plate tectonics. India and Madagascar were once part of the same landmass (Gondwana), but it broke apart; it did not sink into the sea.

Before it was discredited, the Lemuria theory gave credence to the Tamil myth of Kumari Kandam, a continent that allegedly connected India, Sri Lanka, Madagascar and Australia in ancient times. Helena Blavatsky and other theosophists believed it. Charles Webster claimed to have received the ancient wisdom of Lemuria from Theosophical Masters by “astral clairvoyance”. James Bramwell called the Lemurians one of the “root races” of humanity, the other two being the Atlanteans and the Aryans.

Richard Sharpe Shaver popularized the theory of Lemuria in his short stories for Amazing Stories. Lin Carter, another American fantasy author, based several of his stories in Lemuria as well, including The Wizard of Lemuria (1965). The Agent 13 novels of Flint Dille and David Marconi, which were written as a homage to 1930s pulp fiction, feature a mysterious Brotherhood founded by survivors of Lemuria plotting world events from the shadows. Lemuria is mentioned in Mike Mignola’s Hellboy. The 2014 video game Child of Light is set in a mystical land called Lemuria, but it appears to have no relation to the real-world myth.

Hyperborea and Thule

Hyperborea and Thule were both mythical lands in the Far North. The former was known to the Greeks as a land were the sun never set. Thule is commonly associated with Greenland, Iceland and Norway. Occultists in interwar Germany identified it as the homeland of the Aryan master race.

They weren’t the first ones. Jean Sylvain Bailly, a French astronomer and revolutionary, pointed out that, in most ancient mythologies, races originate in the north and then migrate south. William Fairfield Warren argued in Paradise Found (1885) that humanity once inhabited the North Pole and that various mythical lands — Atlantis, Hyperborea, the Garden of Eden — are all folk memories of the same thing. Warren rejected Darwinism and believed the Great Flood had submerged mankind’s Arctic home. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, an Indian nationalist, believed the Vedic people migrated to India from the Arctic region during the last Ice Age.

In the 2009 video game Wolfenstein, the Paranormal Division of the SS (based on the real-life Ahnenerbe) is investigating ruins of the vanished Thule civilization.

Searching for images of “Hyperborea” turns up the artwork of Vsevolod Ivanov, who believed the “Vedic Rus” descended from an alien race. Weird Russia has more.

Atlantis

The ultimate lost civilization. Invented as an allegory by Plato, Atlantis has inspired too many books, movies and video games to count. Wikipedia has a complete list. I’ll focus focus on the most steam- and dieselpunky ones.

We have already met the theosophists, who believed the Atlanteans were one of several great pre-Flood civilizations. “Atlantean” became a shorthand for supreme ancient race. Ignatius L. Donnelly imagined an Atlantean Empire lording over large parts of America and Europe in his Atlantis: the Antediluvian World (1882). The Nazis traced the origins of the Aryan Nordic race in Atlantis.

Professor Aronnax and Captain Nemo visit the remains of Atlantis in Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under The Sea (1870).

In H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Temple” (1920), a German submarine discovers Atlantis when it sinks to the bottom of the Atlantic during World War I.

In The Maracot Deep (1929), Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, describes Atlantis as a high-tech society that is inhabited by people who have adapted to life under the sea. In Carl Barks’ “The Secret of Atlantis,” first published in Uncle Scrooge 5 (March 1954), Uncle Scrooge, Donald Duck and his nephews discover a similar underwater civilization.

In Robert A. Heinlein’s Lost Legacy (1941), Atlantis is a colony of Mu. In the 1982-83 anime The Mysterious Cities of Gold, Atlantis and Mu destroyed each other with nuclear weapons.

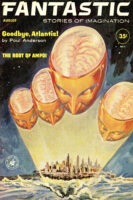

David MacLean Parry’s The Scarlet Empire (1906) and Paul Anderson’s “Goodbye, Atlantis!”, published in Fantastic (1961), both feature Atlantis as something of a communist dictatorship. In the latter, it is destroyed by vengeful gods.

The 1992 video game Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis shows Nazis searching for Atlantis technology.

Disney’s 2001 Atlantis: The Lost Empire featured an early-twentieth-century expedition to find Atlantis in a Nautilus-inspired submarine called the Ulysses.

Atlantis is discovered in Journey 2: The Mysterious Island (2012), which is based on Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island.

Plenty of artists have created their own versions of Atlantis. Here are three examples by Flavio Bolla, Raphael Lacoste and “Gaius31duke“.

Agartha, Shambhala and Hollow Earth

Shambhala is a mythical kingdom in Central Asia or Tibet, supposedly the refuge of the survivors of Lemuria or Hyperborea and a center of spiritual enlightenment.

Jean-Claude Frère wrote that the survivor of Hyperborea settled in a Central Asian city called Agartha, which sunk into the Earth as a result of another catastrophe. In his telling, Shambhala was founded by dissident Hyperboreans who followed the path of the “Black Sun”.

Alexandre Saint-Yves d’Alveydre told much the same story in his Mission de l’Inde en Europe (1886), which for the first time connected the myth of Agartha with that of a Hollow Earth.

The idea that the Earth’s poles provide entrance to the underworld is an ancient one. Edmond Halley (who discovered Halley’s Comet) brought it into the modern world in 1692. The myth inspired Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1838), Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Pellucidar novels, among others.

More recently, it has featured in such dieselpunk fiction as the role-playing game Hollow Earth Expedition (2006) and Iron Sky: The Coming Race (2019, our review here), whose title is drawn from Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1871 theosophist novel.

Something these Hollow Earths have in common, aside from being popular with Nazis: dinosaurs.

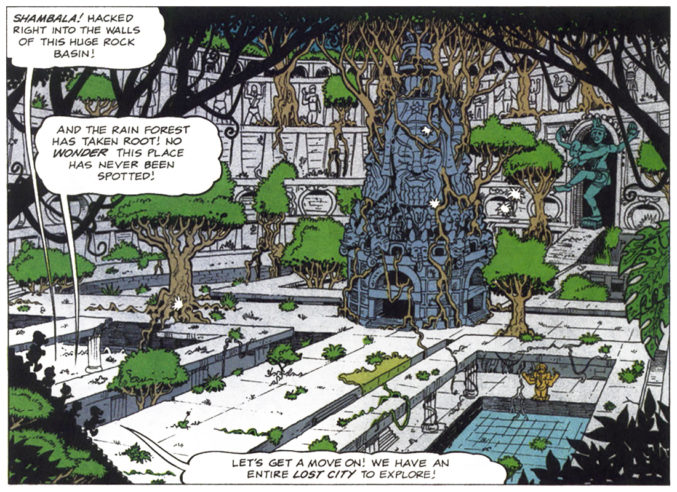

No dinosaurs or esoterica in Duckworld. In “The Treasure of the Ten Avatars,” first published in the United States in Uncle Scrooge Adventures 51 (October 1997), Shambala is simply a long-lost ancient city in India. The author and artist, Keno Don Rosa, was inspired by the Ajanta and Ellora Caves, Buddhist and Hindu cave monuments in what is today Maharashtra state that were cut out of rock.

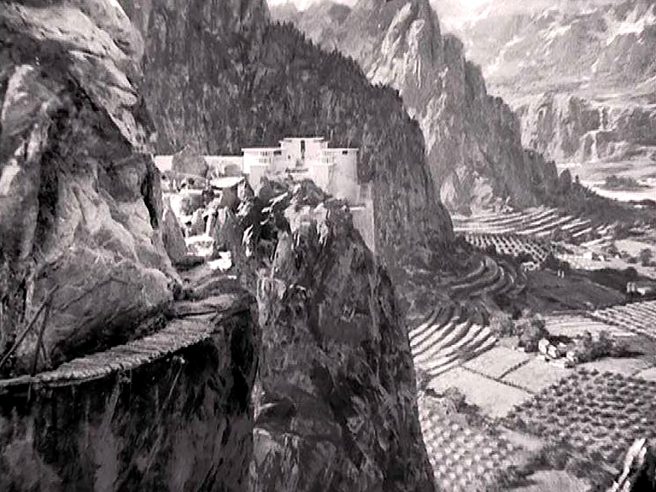

Shangri-La and Xanadu

James Hilton was probably inspired by the myth of Shambhala when he invented Shangri-La in Lost Horizon (1933). It also sounds similar to the pleasure land described by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in the poem “Kubla Khan”, which was based on the old Chinese capital of Xanadu.

Lost Horizon was adapted into a movie twice, in 1937 and 1973. Shangri-La’s appearance in the first inspired the idyllic Valley of Tralla La in Carl Barks’ 1954 Uncle Scrooge comic. Keno Don Rosa revealed Tralla La to be Xanadu in his sequel to Barks’ story, “Return to Xanadu,” first published in the United States in Uncle Scrooge 261 (December 1991).

Shangri-La also appears in dieselpunk favorite Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004).

Tartaria

A modern-day mix of Hyperborea and Shangri-La, Tartaria, or Tartary, is an internet conspiracy theory that posits an early-modern empire in Northeast Asia spread its Beaux-Arts architecture from the Bund of Shanghai to the Plains of North America, but was deliberately written out of the history books by a conspiracy of Communist and Western powers. The theory explains everything from the demolition of “world’s fairs” — in reality, Tartaria’s moving capital — to the destruction of cathedrals and churches in Soviet Russia.

Click here to read more.

El Dorado and the Seven Cities of Gold

There are several American city-of-gold myths, the most famous ones being El Dorado and the Seven Cities of Gold. The former was supposed to be hidden in the jungles of Colombia; the latter in New Mexico. Numerous expeditions were undertaken by adventurers and conquistadors during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in search of both.

Scrooge McDuck and his nephews discover both lost lands: in Barks’ “The Seven Cities of Cibola,” first published in Uncle Scrooge 7 (September 1954), and Rosa’s “The Last Lord of Eldorado,” first published in the United States in Uncle Scrooge 311 (May 1998). The second story makes reference to the El Dorado expeditions of Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, Nicolaus Federmann and Sebastián de Belalcázar.

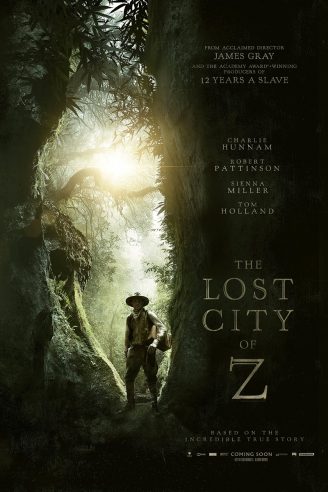

British adventurer Percy Fawcett searched for a similar city in the Amazon rainforest known as “Z”. His quest was turned into a book by David Grann (2009) and a movie by James Gray (2016).

In Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), El Dorado and the legendary Inca city of Paititi are revealed to be the same place, called Akator.

1 Comment

Add YoursThis article reminded me of a series of 1970s movies all featuring lands falling into these categories. There was ‘The Island at the Top of the World’ (1974) about an English explorer, played by Donald Sinden, in 1907 going to a temperate land in the Arctic where a Viking civilisation lived on. However the greatest proponent of this genre in movies at the time was British director Kevin Connor (born 1937) casting US actor Doug McClure (1935-95) in a heroic role. There was ‘The Land That Time Forgot’ (1975) based on an Edgar Rice Burroughs novel from 1924, featuring the island of Caprona visited by a German U-boat and British prisoners, including McClure’s character, during the First World War. Caprona has dinosaurs and primitive humans living on it, a little like the later ‘Dinotopia’ (1992 and subsequent books). There has been a 2009 remake bringing it up to date, set in the Bermuda Triangle and featuring a U-boat wrecked there, presumably in reference to the 1975 movie. That movie was so successful that there was a sequel ‘The People That Time Forgot’ (1977), based on two books by Burroughs from 1924. In this one, a friend comes to rescue McClure’s character from Caprona.

Another Connor-McClure movie based on a Burroughs story was ‘At the Earth’s Core’ (1976). It drew on the first of Burroughs’s Pellucidar novels, published in 1914, about a hollow Earth. Using a wonderful steampunk ‘mole’ device, a British scientist played by Peter Cushing along with a US financier, McClure, bore into the hollow Earth to find telepathic flying reptiles who have enslaved humans there. The last in this flurry of such movies, once more directed by Connor and starring McClure, was ‘Warlords of Atlantis’ (1978). It has a similar approach with an archaeologist using a diving bell, leading him and his companions into danger when attacked by monsters sent out by the eponymous warlords who rule an underwater world of Atlantis. They are highly advanced but cruel and subjugate humans, including everyone from the ‘Marie Celeste’ and have prehistoric monsters under their control. These Atlanteans had supposedly come from Mars.

While these were crowd-pleasing movies fitting a set formula, it is interesting to see this burst of movies set around these long imagined worlds, often using Steampunk themes as well as more fantastical concepts in the stories. They certainly intrigued me as a child and perhaps contributed to my interest in Steampunk and associated tropes.