As soon as the Second World War was over, military strategists started planning for the next one.

Life magazine reported in its November 19, 1945 edition that the head of the United States Air Force, General Henry H. Arnold, had warned that technologies developed during the last war — atomic bombs, ballistic missile, long-range bombers — could make possible “the ghastliest of all wars.”

The destruction caused by nuclear weapons would be so swift and terrible that a “war might well be decided in 36 hours.”

Life envisaged what such a war might look like.

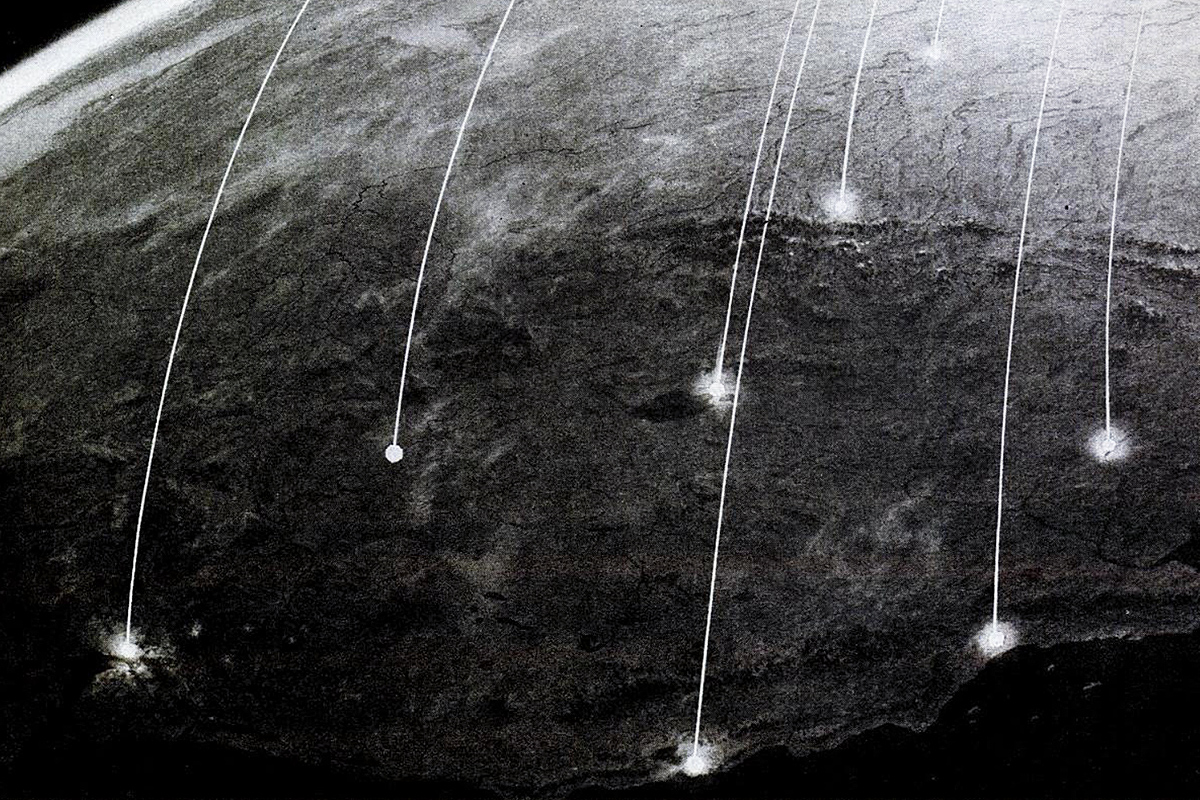

“Atom bombs descend on the United States”

The start of the next war, said General Arnold, might come with shattering speed:

With present equipment, an enemy air power can, without warning, pass over all formerly visualized barriers and can deliver devastating blows at our population centers and our industrial, economic or governmental heart even before surface forces can be deployed.

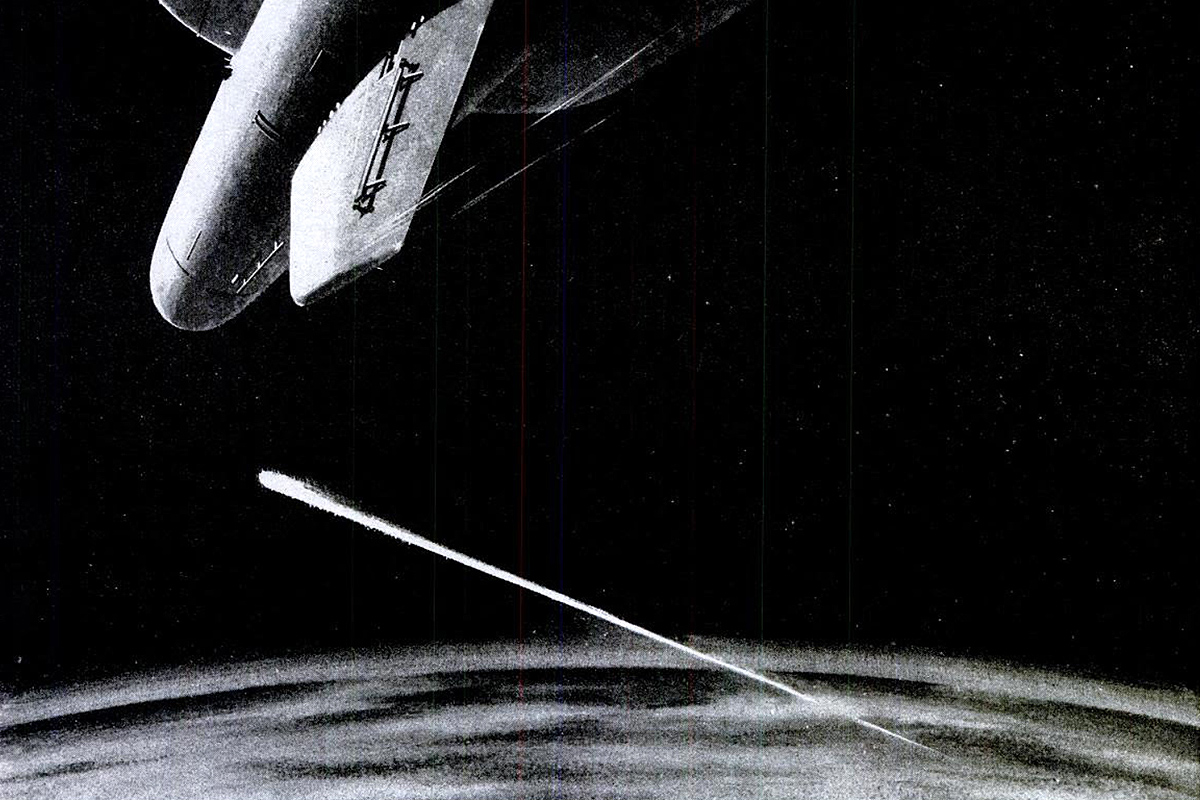

“Radar centers follow course of rocket war”

Life imagined that radar would be able to detect incoming missiles, plot their course and feed the data to electronic calculators in defensive rockets. These would then be launched in a matter of seconds to intercept the attackers.

In reality, the military is still struggling to make such a system work seven decades later.

“Our defensive machines stop few attackers”

The only defense against a rocket, once it is in flight, is another rocket, fired like an anti-aircraft shell at a point where it will meet its enemy.

Once launched, such a rocket might detect the incoming machine with radar and make its own corrections. When it came near the enemy rocket, it could be exploded by radio proximity fuze, a development of World War II.

But inevitably it would miss some of the time.

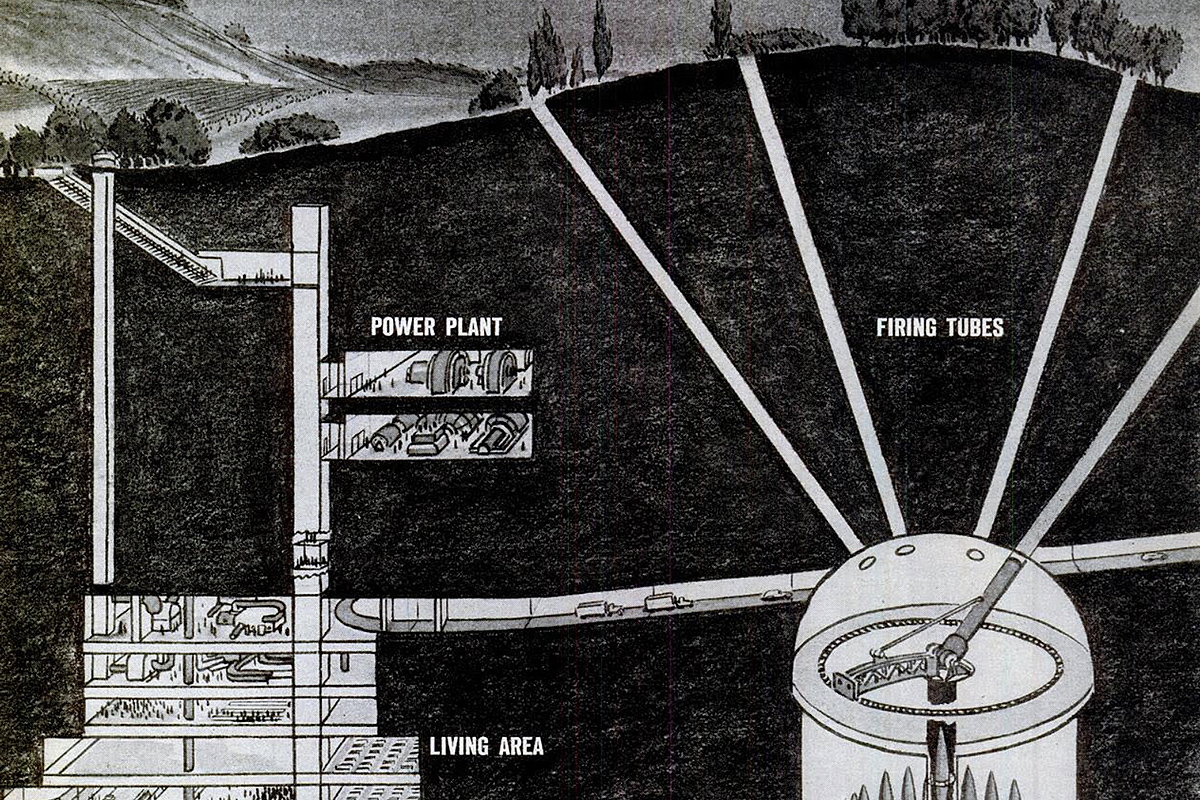

“America makes its counterattack”

General Arnold already understood the meaning of mutually assured destruction.

Real security against atomic weapons, he argued, “will rest on our ability to take immediate offensive action with overwhelming force.”

It must be apparent to a potential aggressor than an attack on the United States would be immediately followed by an immensely devastating air-atomic attack on him.

Life imagined underground rocket-launching sites and atom bomb factories to enable such a response.

“Enemy airborne troops come in”

In spite of the apocalyptic destruction caused by nuclear war, Life expected that an enemy would still need to invade the United States in order to win it.

The magazine projected forty million dead, the destruction of all major population centers — and yet was confident America could prevail.

The enemy airborne troops are wiped out. US rockets lay waste to the enemy’s cities. US airborne troops successfully occupy his country. The US wins the atomic war.

Victory!

2 Comments

Add YoursInteresting. No other country had nuclear weapons in 1945, yet the authors have already redefined ‘Victory’ in a very pyrrhic way.

“In reality, the military is still struggling to make such a system work seven decades later.”

True, though more a struggle about politics and money than technology. Politicians and others still have mixed feelings about such defences and many still revere Mutually Assured Destruction as a secular dogma.

I was always rather unsettled seeing ‘The Time Machine’ (1960) movie as it features the Victorian time traveller stopping some time in the 1960s and speaking with a man he had first met near the end of the First World War, but this time the Third World War was under way. It was uncomfortable that a movie simply assumed that there would be such a war, even though I should have realised when I saw the movie on television in the 1970s, that we were past the period it showed it happening.

Then, of course, we were all scared at school by being shown ‘Threads’ (1984) which has been re-released on DVD this year and ‘The Day After’ (1983) being on television. I definitely remember the certainty of my school teachers that there would be a nuclear war before we had grown to maturity; they spoke about it openly. We always got jumpy when there was a loud bang at night or a military helicopter flew over.

I lived near a NATO base and so we were ‘reassured’ that we would be eliminated in the first wave of nuclear missile attacks and not suffer the lingering deaths shown in these dramas. I know young people have a lot to worry about today, but the certainty, so common in the 1980s, that we would be burnt to ash or die slowly from radiation sickness, is one thing that is not as apparent now.