After World War II, the Allied powers ceded the German lands east of the Order and Lusatian Neisse rivers to Poland, creating a border dispute that would last through the entire Cold War.

It were the Soviets who insisted on the change. Joseph Stalin wanted to annex the Eastern Borderlands of the former Polish Republic — which were only lightly populated by ethnic Poles — to Russia proper while still putting a strong Polish buffer state in between itself and Germany. Hence the need to add Germany’s eastern provinces to the new Poland.

The north of East Prussia, around the city of Königsberg, was sliced off to create Kaliningrad for Russia, giving it the warm-water port on the Baltic Sea it had long coveted.

The Americans and British felt this dismemberment of Germany went too far, but they eventually relented at Potsdam in the summer of 1945 under a combination of Soviet intransigence and pressure from the Soviet-aligned Polish government.

The Western Allies were also led to believe there were only around one million Germans still living in East Prussia, Eastern Pomerania and Silesia. In fact, there were millions. Up to 31 million ethnic Germans and German citizens were cleansed from Eastern Europe after the war. Between 12 and 14 million resettled in Austria and West Germany. Recent studies suggest around half a million died in the expulsion.

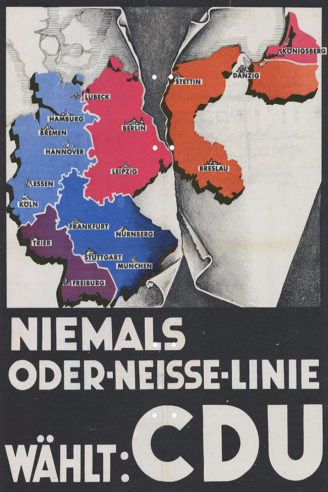

Niemals Oder-Neisse-Linie

Both East and West Germany were unhappy about the new border, but the former — under communist dictatorship — was strong-armed by Moscow into accepting what it would half-heartedly agree to call the Friedensgrenze (“Border of Peace”). In 1950, the German Democratic Republic and Poland formalized the Order-Neisse frontier in a treaty.

Not so West Germany. It insisted that the Potsdam Declaration had been provisional and the German lands east of the Oder-Neisse were “illegally” occupied by Poland and the Soviet Union.

There was an irony to this legalistic argument: the pre-World War II German-Polish border had been drawn by Germany’s enemies from the last war. In the interwar period, German leaders had rejected the Versailles Treaty as an unacceptable diktat that stranded ethnic Germans in Poland. Now they fell back on it to argue against a second, even worse border revision.

Political motive

Historians still debate if Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first postwar chancellor, sincerely believed in Heimatrecht (“right to one’s homeland”). But there is little doubt he had a political motive for supporting it.

In the dark days after World War II, Adenauer’s Christian Democrats zealously guarded their right flank lest a nationalist competitor emerge and take Germany back into the past. That’s why they fought denazification and even accepted former Nazi officials in the Bonn government.

When a new political party representing the millions of Germans who had been forced out of the East won 6 percent of the votes in 1953 — and higher percentages in some state elections — Adenauer felt he could not ignore them. Leaders of the All-German Bloc/League of Expellees and Deprived of Rights were given relevant cabinet posts. A Federal Expellee Law was enacted, which extended citizenship to all refugees.

Once the law was in place, and the German economy began to recover, the expellee cause lost momentum.

Four years later, the same party failed to cross the 5-percent election threshold. It merged with the remnants of another right-wing party in 1961 but again failed to qualify for seats in parliament.

“The open German question”

Even if there seemed to be little political gain in holding out anymore — and it certainly won Germany no favors in other Western capitals, where its allies wanted to move on — the Christian Democrats still refused to accept the Oder-Neisse line.

It was the first postwar chancellor of the Social Democratic Party, Willy Brandt, who normalized relations with the East in 1970 by recognizing the frontier as the present reality and vowing that Germany would not seek to revise it by force.

German expellees were still not allowed to return to the land of their birth, but visits became a little easier.

The Christian Democrats criticized this Ostpolitik and continued to campaign on what they referred to as late as 1980 as “the open German question”.

Reunification

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, and reunification became possible, the Christian Democrats were still ambivalent. Helmut Kohl, the conservative chancellor at the time, rubbed his allies the wrong way when he conditioned West German acceptance of the Oder-Niesse line on Polish reparations for the Germans who had been expelled in 1945. An international backlash forced Kohl to reconsider.

The two Germanies reunited in October 1990. A month earlier, the former occupying powers — Britain, France, Russia and the United States — had renounced all rights they still held in Germany in the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany: the peace settlement Potsdam had envisaged. This allowed the German parties to accept the Oder-Neisse border in a separate treaty with Poland that same year.

The German and Polish governments also signed agreements recognizing the cultural and political rights of their respective minorities.

At the time, around 150,000 Germans still lived in the areas that had been transferred to Poland in 1945, the majority in Upper Silesia.

Since 2004, when Poland joined the European Union, the border that was once so contested has existed only on paper. 670,000 Polish nationals now live and work in Germany. Another 2.8 million Germans, or 3 percent of the population, claim Polish roots.